Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.15 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2013

Encouraging Students to Enhance Their Listening Performance

Cómo animar a los estudiantes para que mejoren su desempeño en comprensión oral por sí mismos

Sonia Patricia Hernández-Ocampo*

María Constanza Vargas**

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia

* E-mail: hernandez-s@javeriana.edu.co

** E-mail: tatinavgv@gmail.com

This article was received on January 11, 2013, and accepted on July 2, 2013.

Spanish-speaking students constantly complain about the difficulty they have comprehending spoken English. It seems teachers do not often provide them with strategies to alleviate that. This article reports on a pedagogical experience carried out at a Colombian university to help pre-service teachers at an intermediate level of English to improve their aural comprehension. The students were given the task of designing listening activities to be worked on as micro-teaching sessions and were asked to describe their experience by answering a survey. The results showed that students developed the ability to think critically since they needed to make the best decisions regarding the audio level and the design of the activities. They also appeared to have become more autonomous as they realized they could be responsible for their improvement in listening. Additionally, there were evident changes in the teachers' roles.

Key words: Autonomy, critical thinking, teacher's role, teaching listening.

Es común que los hablantes de español se quejen de su comprensión oral en inglés. Parece que los profesores no siempre dan a sus estudiantes estrategias para mejorar al respecto. En este artículo se describe la experiencia pedagógica desarrollada en una universidad colombiana con el propósito de ayudar a los estudiantes de inglés intermedio de una licenciatura a mejorar su comprensión auditiva. Se pidió a los estudiantes desarrollar actividades de escucha para ser trabajadas en sesiones de microenseñanza y describir su experiencia, contestando una encuesta. Los resultados evidenciaron que los estudiantes desarrollaron su pensamiento crítico en la medida que necesitaban tomar decisiones con respecto al nivel de dificultad del audio y al diseño de las actividades mismas. También se mostraron más autónomos por cuanto se hicieron conscientes de su responsabilidad en el mejoramiento de su comprensión oral. Adicionalmente, se dieron cambios en los papeles del profesor.

Palabras clave: autonomía, enseñanza de comprensión oral, función del profesor, pensamiento crítico.

Introduction

The present article intends to show what has been done in the field of linguistics, say teaching English to future English teachers, in order to help the students enhance their listening skill. Now, teaching a language means not only teaching the fundamentals of it but also abilities and strategies that help the learners improve their performance on it, so that they can really communicate.

Concerning a foreign language like English, we must talk about non-native users of English who use the language to communicate with others or to teach others how to use it. This is our case. As teachers, we try to teach our student-teachers how to use English properly. This arduous task involves, of course, the teaching and acquisition of the four skills: writing, reading, speaking, and listening.

Now, it is common to hear English students say that one of the biggest difficulties they have is to comprehend spoken English and to obtain good grades on listening exams. For them, it is easier to get to write in English and comprehend written texts than to have a good performance in listening and speaking. In addition, it is common for teachers to tell their students they will improve their speaking ability if their listening skill is enhanced. However, it is not common that teachers tell the students how they can go about doing it, and it is very likely that the students do not know how to practice listening on their own, as we have evidenced with our students.

That is precisely our purpose with this document: to show the reader one of the things that can be done in order to help students with their learning and listening comprehension. To do that, we will start by describing the three pillars we consider are the ones involved in the project: teaching listening, autonomy, and critical thinking. Afterwards, a descrip tion of the project will be provided, as well as the results obtained.

Three Axes to Consider

First, it is important to know about the characteristics of our learners: they are future teachers since they are majoring in Modern Languages at Javeriana University. The course is intermediate English, which means most of them are in fifth semester and have been taking 10-hour-a-week English classes for two years. According to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, they would be classified in level B2; this implies that they "can understand extended speech and lectures and follow even complex lines of argument provided the topic is reasonably familiar. [They] can understand most TV news and current affairs programmes. [They] can understand the majority of films in standard dialect" (Pearson Longman, n.d., p. 5). However, our students' enduring complaint is that it is complicated to understand any audio text when the dialect is different from the American one. Our discernment, as teachers, is that it is not only the dialect but also the pace and the task proposed that prevents them from obtaining good results.

Considering that the project has been developed in order to help those students enhance their listening performance, and also considering the fact that reminding the students they have to do extra practice on their own—since what is done in class is never enough—does not mitigate the problem, we feel there are three axes to consider: Teaching Listening, Autonomy, and Critical Thinking.

Teaching Listening

This is not an easy task because listening involves going through a lot of mental processes, from distinguishing sounds to knowing a grammatical rule. In addition, we as teachers fall into the habit of having our students practice listening, but we do not tend to teach them how to listen. Obviously, practice plays an essential role in developing the listening skill; however, the way such practice is done is a key factor in developing the skill more effectively.

In the classroom, for instance, we should take into account the understandable input we must use and the affective factor for listening comprehension (Krashen, 1981). In addition, we have to emphasize two different processes to be used when listening to an oral text and trying to understand it: bottom-up processes and top-down processes (Richards, 1990). The first ones involve the linguistic knowledge one possesses to decode the message, so it involves knowing, for example, how words link together, how some sounds disappear, and how grammar helps to guess meaning. The second ones, top-down processes, deal with the previous knowledge the listener has about the topic and how he associates this prior knowledge to the information he listens to in order to enhance comprehension.

This all brings up the complexity of the listening skill; nevertheless, the way listening comprehension is taught might make the needed skills even more difficult to acquire. We should get our students aware of these processes at the time they are doing a listening exercise. For example, we can teach them that their knowledge about the language (prepositions, collocations, tenses, subject-verb agreement, etc.) will help them make predictions of the words that will follow in a sentence depending on the context, of course (bottom-up processes). Also, we can have them realize the importance of reading the instructions and the questions before doing the task in order to activate their knowledge of the vocabulary related to the topic and, in this way, improve their listening comprehension (top-down processes).

Not only is it necessary to include conscientious listening strategies in our classes to improve our students' listening comprehension, it is also important to provide our students with an appropriate environment that helps them in the acquisition. Here, Krashen's (1981) affective filter hypothesis plays an important role, as does his input hypothesis. The first one refers to lowering students' stress and anxiety as they are doing a listening exercise because motivation and selfconfidence encourage language acquisition. The second one refers to providing students with comprehensible input that is a little higher than what they can produce and with enough input of this kind they will acquire the language. Language acquisition then involves practicing the language in real contexts or in situations similar to the real use of the language without feeling stressed or anxious. As teachers, we can help develop such acquisition by choosing the appropriate audios for our students and by motivating them to do listening activities in a comfortable environment.

Autonomy

This is the second idea behind the project. Autonomous learners are more effective learners and therefore more motivated learners. According to Benson (2001, p. 47), "autonomy is generally defined as the capacity to take charge of, or responsibility for, one's own learning." What this means is that autonomous learners are able to control three aspects of the learning process: their cognitive processes, the content they are learning, and the way they are learning. In exercising this control, learners use different strategies: metacognitive, cognitive, and socio-affective strategies. The first ones enable the student to reflect on the learning process by planning, managing, monitoring, and evaluating learning tasks; cognitive strategies are the particular exercises or actions students take with the material to be learned; socio-affective strategies involve working or interacting with others to improve learning.

According to Vandergrift (2002), skilled listeners use more metacognitive strategies than their counterparts: "When listeners know how to ... analyze the requirements of a listening task; ... activate the appropriate listening processes required; ... make appropriate predictions; ... monitor their comprehension; ... and evaluate the success of their approach, they are using metacognitive knowledge for successful listening comprehension" ("Listening in Language Learning and Teaching," par. 1). Developing metacognitive knowledge in our students is, therefore, critical for the effectiveness in their listening skill. Vandergrift proposes a pedagogical sequence to practice listening and help students develop metacognitive knowledge: The first step is having pre-listening activities which prepare the students for the content they are to listen to and the task they have to do; in pre-listening activities students are aware of their knowledge about the topic, can make predictions about the oral text and can focus on the particular information they need in order to do the listening task. The second step is monitoring listening comprehension; in this step, students make decisions on what strategy they need to use during the listening task, check their predictions and check their comprehension of the oral text. The third step involves assessing the effectiveness of the strategy used during the listening task. It is imperative then to encourage our students to follow these steps to become more autonomous listeners. Hopefully, with the practice of these steps when doing listening exercises, they will eventually be more likely to practice on their own in order to improve their listening skill.

Critical Thinking

Paul (1992) states that it is only when we have one problem to solve that we think critically. In order to solve a problem, we first need to analyze its nature then come up with different ideas to solve it, evaluate these ideas, and make decisions to choose the best alternatives. These processes require high order thinking skills that improve our own thinking. But improving our thinking not only implies analysis and decision making but also assessing our thinking (analysis, decisions) using intellectual standards as Paul suggests. Intellectual standards are used to get students to check or assess the quality of their judgements. They include clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, and logic. Teachers can teach these standards by posing questions to students about their reasoning.1 Therefore, getting our students to solve problems is not enough to turn them into critical thinkers; they need to assess their analyses and decisions in solving problems by using the abovementioned intellectual standards. All in all, critical thinking is, in Paul's words, "thinking about your thinking while you are thinking in order to make your thinking better" (par. 3).

The Project

Conscious of the need to guide our students in their language acquisition and autonomous work, we have included a listening project in our classes as a way to help them improve their listening skill. The project was carried out in a teaching degree program with intermediate students of English; the project—which is currently being developed not only in the intermediate level classes, but in others—was run for two semesters in 2010-2011. The information was collected in two classes, with an average of 20 students each.

In the project, students were to look for an authentic audio text and create an activity with which they and their partners could have good practice. In this way, our students were making use of the language in real contexts, which might help them enhance their understanding when they listen to English in authentic situations (Field, 1998) and they could practice listening in an atmosphere where they were relaxed, not stressed as is the case of class exercises and exams. As Krashen (1981) suggests, reducing stress enhances language acquisition.

The first condition for the students to do the activity was that the audio had to be authentic, so that they could become familiar with the characteristics of natural speech (Field, 1998). That means that they were not allowed to choose any audio that came from textbooks. Instead, they had a wide variety of sources such as magazines, websites, podcasts, songs, movies, and so forth. The constraint related to textbooks is due to the fact that they have adapted audios; therefore, they are not real life examples of what an English learner might be exposed to. Students must also consider the level of the audio, neither too high nor too low, but according to their language level (Krashen, 1981). On this first condition, the students faced a problem: to decide which audio would match best with their level.

The second condition was that they had to identify the type of task they had more difficulty with. Thus, the students were obliged to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses to distinguish the latter and try to compensate for them, which would somehow enable them to be critical about their learning process (Paul, 1992). Besides, as the groups were varied— what might be a strength in one student might be a weakness in another—this resulted in diverse types of challenging tasks.

The third condition consisted in designing a pre-listening, a while-listening, and a post-listening activity. Here they faced the responsibility of designing a creative pre-listening activity to get their partners' attention, which was as important as a well-designed post-listening activity that kept the audience involved.

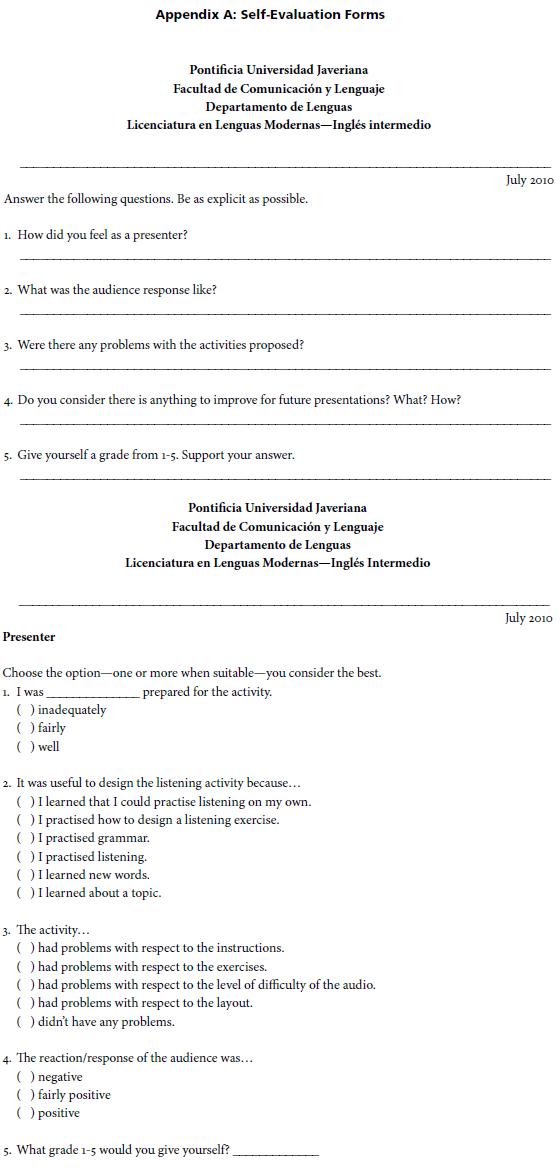

Student-presenters, in a micro-teaching situation, gave their partners the activities they themselves. The whole situation lasted for about half an hour. Once the presentation was over and all the class had done the proposed activities, it was time for evaluation: self and peer evaluation (see Appendixes A and B). The class was to evaluate the presenters as "teachers" and so were the student-presenters, who did self-evaluation; assessment focused on the design of the activities. As a consequence, the students were learning how to assess themselves and their partners; they became more responsible as they recognized weaknesses, not only in their partners but also in themselves and became aware of what they could do on their own to their benefit.

Towards the end of the semesters, after having three micro-teaching sessions with different audios and activities per pair, a general evaluation of the project took place. It was a blind open question survey2(see Appendix C) in which they were asked about their feelings towards the assignment, the difficulties they had had, and the gains they made, as well as suggestions and complaints.

The above resulted in students being reflective upon and critical of their performance; they were to identify strengths and weaknesses and go beyond that by getting into action. It is valuable that they could say what their difficulties were and then tried to alleviate them by doing the exercise of designing listening activities as proposed.

Results

The results are based on the information collected through the survey to assess the project as a whole. All students in the two classes answered the survey. The analysis of the information was a qualitative one; the data were analysed so that some categories emerged according to repetition of information relating the criteria in the survey: feelings as a "teacher," feelings towards peer and self-evaluation, gains, suggestions. The findings were classified into four categories: Performance, Critical Thinking and Autonomy, Playing the Teacher's Role, and Assessment.

Performance

All the students reported having an important gain: The listening project has helped them comprehend spoken English better, apart from giving them the chance to practice speaking. They commented that there had been a certain amount of improvement in the different skills, especially in listening, as well as in the acquisition of new vocabulary and improvement in pronunciation; besides, it gave them the opportunity to learn about new topics different from the ones they see in their textbooks. Students also claimed they had gotten some new practice when listening: "Now I try to get the whole idea the first time I listen to the audio and, after that, I try to answer the tasks that are asked;" "[I have learnt] to do charts, to classify the information, to infer;" "Now I try to understand little details, not only the general idea."

With regard to the common complaints about the difficulty in understanding when it was a dialect different from the American, they stated that they could understand different accents better: "It helps us to improve our comprehension of different types of voices;" "I have better understanding even with fast audios," referring to the pace of the speech, they said. Furthermore, many said they had made some progress in the exams, although this was not the purpose of the project. With respect to this, it is important to add that not all the students made the same progress, as it would depend on every student's level of proficiency; some of them did not even pass their exam(s)—"I don't have a good listening [performance], but the project is a good practice for our listening exams"— but experienced such an important advance in listening comprehension that they felt more confident as they recognised their weaknesses and got ideas on what to do to alleviate them.

It is obvious that the students were exposed to a lot of input that maybe helped them acquire the language (Krashen, 1981); in other words, this input promoted the use of the language in a subconscious way and made them feel more comfortable when listening to an audio for a quiz or an exam.

On the other hand, when asked about their feelings when performing as presenters, students said they had felt nervous, intimidated, stressed, scared, and sometimes confused and disappointed: "I felt stressed because the audience didn't want to participate;" "nervous because I didn't know how to explain the instructions;" and "I felt scared because I don't like to stay in front of many people." Others said they had felt disappointed because the results were not what they expected. Nevertheless, not all of them had bad feelings as presenters; many of them reported feeling comfortable and added that it was a very good experience as "you learn how to manage the audience."

Students were also asked about their feelings as members of the audience. Regarding this, most of them reported to have felt interested as there were different topics on culture, history, science, and medicine, among others; they also said they felt relaxed and expectant: "I felt more confident and relaxed when listening, which allows me to think more clearly." Also, some added that they had felt more secure because they did not have to speak before the audience. However, others said they felt a little bored because there were too many exercises of the same kind.

Critical Thinking and Autonomy

As we know an autonomous learner is one who thinks critically and a critical thinker makes an autonomous learner, we decided not to separate the findings on these. The students admitted that it had been hard to find an appropriate audio according to their level. They were aware of the fact that they had to design something for the others to approve and find useful: "Something that was kind of difficult was to create something new and appealing for the others." Besides, the students became more acquainted with their active role in their learning process: "I have learned that I must do my job conscientiously." "It is useful because you can see what you need to improve."

Furthermore, as said before, some students realised that they can do a lot to alleviate their limitations—at least, they were aware of the many sources they could access to get extra practice on their own: "I learnt that I can do exercises by myself and that I can use the internet to do them;" "I found that I can use the podcasts and news with listenings (referring to audios) to improve my listening and vocabulary." This shows that students are becoming more responsible for their own improvement. All of them confessed to having done more work at home as they have learned that they can find a lot of web pages to practice with on their own. Also, they realised, while looking for the audios to do the exercises, that there are a lot more activities for practising themselves. They claimed to have learned about the wide variety of resources the Centro de Recursos (Resources Center) offered, apart from the web pages they found such as: http://www.unicef.org, http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio/podcasts, http://www.sciam.com/podcast

Playing the Teacher's Role

Our students, as stated before, will become language teachers once they finish their major (at least, that is the preparation they are receiving). The project allowed the students to take the role of a teacher: "I felt as a teacher," "it helped us to analyse ourselves as teachers," they commented. Others, thinking further about what being a teacher means, assured us that the project helped them think of how to prepare a class taking the students' characteristics into account: "You have to design challenging exercises, not only fill-inthe-blank activities because they are repetitive and don't allow the students to think." Similarly, some recognised they could be more creative which, they acknowledged, is good for them as future teachers.

They also realized that being in front of the audience implies some form of control over it. They felt that was challenging as they said it was difficult "to catch the attention of the class because to control the group is very hard" and, sometimes, "it was difficult to give clear instructions." Clarity of instructions, we must say, improved as they did the project a second and third time. So, we could notice students took the feedback into account every time they did their presentations.

Others recognized they had learned how to control their fear of speaking in public, as it also improved through the different presentations they did. Besides, some said to have been trained in evaluation, as they had to assess their partners. Although in the beginning it was taken as "if the presenters are my friends, I will give them a good grade"—to put it in the students' words—they turned out to be more objective towards the end of the semester: They justified the score they gave their partners. All the students considered these aspects to be very helpful as they will be in front of a group soon, and will have to evaluate them as teachers.

Assessment

Although most of the students reported finding peer evaluation useful, a few did not agree: "Peer evaluation is not useful because the majority of them [the students] don't take the suggestions into account; they just want a good grade, but it is not like that;" Some felt that the comments made by their peers were not fair as they considered their peers to be evaluating the topic instead of the activity itself. Others, instead, recognised the importance of it since they found it useful to have another point of view different from the teacher's. With regard to the role of evaluating their peers, they said it was interesting as "it helps you know what it is like to be a teacher." They were able to suggest to their partners what to improve and most of them were serious when doing it. All of them reported having evaluated their partners conscientiously.

Moreover, they valued the importance of feedback in learning: "The learning process implies good feedback and we had it," they affirmed.

Conclusions

It is important to highlight the fact that many of the students were aware of their problems with pronunciation and grammar, besides their low performance on listening, which reinforces the idea of the project being helpful to lead students to an improvement of other skills/components of the language.

The project required the students to make decisions about the topic and material they would use in their presentations, as well as about the activities they would plan. This involved reflecting on their performance to identify strengths and weaknesses and, based on that, analyzing and judging sources and methodology, which reflect the use of the critical thinking skills Paul (1992) talks about.

In the same way, although some students did not design the exercises themselves, they were useful because they had to make decisions on what to use and how to adapt them, taking into account not only their needs, but also their peers'. Some others took already designed exercises as a reference to design their own; that move implied decision making as well, as they had to decide if the level was proper and if the type of exercise was interesting enough to be presented.

As long as the projects were presented, students became more demanding with respect to the difficulty of the audio, the design of the exercises and the type of activities, which shows they were really concerned about their need to enhance their performance. They were being critical of and took responsibility for not only their own performance but also their peers', following what Paul, Willsen, and Binker (1993) and Benson (2001) state.

Thus, some students have gone beyond recognising their weaknesses by using their own strategies to lessen them. They considered the project to be very helpful since it made them aware of the many possibilities of working on their own; they are becoming more autonomous. They really felt there was some improvement in their performance on listening (which was what we aimed at with the project), although it did not guarantee obtaining good grades—at least the ones they expected—on their tests.

As for language acquisition, students had to choose an audio that was at a higher level than the level they use to produce the language which involved the kind of input that Krashen (1981) says is necessary to acquire a language. In the same way, students had the chance to practice listening in a relaxed environment since the ones who were not the presenters had to do the exercise without the pressure of a grade for their performance. This involves the second point made by Krashen about motivation and self-confidence, which promote language acquisition.

By evaluating themselves and their peers, students will become more analytical and critical. Thus, when they become teachers, they will have been faced with evaluating and, somehow, will have some confidence in the process and will take it more into consideration as they will have reflected on all that it implies.

Students played the role of a teacher and realized that it implied being creative, taking the students' characteristics into account to design the activity, controlling the group, keeping the group's attention, and challenging the students to get good responses. They felt it was difficult but liked the experience a lot.

There was a change of roles. Our students were given the responsibility for some functions that traditionally have been in teachers' hands. This has led us to confront our own practice; we have begun reflecting upon our role as guiding agents, not as providers.

Notas

1For an example of a set of questions about depth, let's quote Paul and Elder (2007, p. 11): "Depth: How does your answer address the complexities in the question? How are you taking into account the problems in the question? Is that dealing with the most significant factors? A statement can be clear, accurate, precise, and relevant, but superficial (that is, lack depth)."

2The students were not asked to identify themselves when answering the surveys.

References

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Essex, UK: Longman. [ Links ]

Field, J. (1998). Skills and strategies: Towards a new methodology for listening. ELT Journal, 52(2), 110-118. [ Links ]

Krashen, S. D. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning [HTML version]. Retrieved from: http://www.sdkrashen.com/SL_Acquisition_and_Learning/cover.html [ Links ]

Paul, R. (1992, April). Critical thinking: Basic questions and answers [Interview for Think Magazine]. Retrieved from http://www.criticalthinking.org/aboutCT/CTquestionsAnswers.cfm [ Links ]

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2007). The miniature guide to critical thinking: Concepts and tools [PDF version]. Retrieved from http://www.d.umn.edu/~jetterso/documents/CriticalThinking.pdf [ Links ]

Paul, R., Willsen, J., & Binker, J. A. (Eds.). (1993). Critical thinking: How to prepare students for a rapidly changing world. Santa Rosa, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking. [ Links ]

Pearson Longman. (n.d.). Teacher's guide to the Common European Framework [PDF version]. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonlongman.com/ae/cef/cefguide.pdf [ Links ]

Richards, J. (1990). The language teaching matrix. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Vandergrift, L. (2002). Listening: Theory and practice in modern foreign language competence. Retrieved from: https://www.llas.ac.uk/resources/gpg/67 [ Links ]

About the Authors

Sonia Patricia Hernández-Ocampo is an English teacher at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Colombia). She earned a master's degree in Education at the same university. She has designed material for the Language Department's distance English program. Her interests also include evaluation in education.

María Constanza Vargas has studied and worked in Colombia. She holds a BEd in Modern Languages from Universidad de los Andes and the certificate of "Especialista en Docencia Universitaria" from Universidad del Rosario. She has worked as a coordinator in the English Department at Politécnico Gran-colombiano and as materials designer for the Virtual English courses at Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Currently, she works as an English teacher at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.