Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.17 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2015

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44393

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44393

Reflective Teacher Supervision Through Videos of Classroom Teaching1

Supervisión colaborativa docente a través de clases grabadas en video

Sandra Mari Kaneko-Marques*

Universidade Estadual Paulista "Júlio de Mesquita Filho," Araraquara, Brazil

This article was received on July 11, 2014, and accepted on January 30, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Kaneko-Marques, S. M. (2015). Reflective teacher supervision through videos of classroom teaching. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(2), 63-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44393.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The main objective of this paper is to briefly present roles of different teacher supervisors according to distinct models, highlighting the importance of collaborative dialogues supported by video recordings. This paper will present results from a qualitative study of an English as a foreign language teacher education course in Brazil. The results indicated that collaborative supervision was an efficient tool to address adversities within educational contexts and that student teachers who observed their pedagogical actions through videos became more reflective and self-evaluative, as they provided a deeper analysis regarding their practice. With collaborative supervision, teacher candidates can be encouraged to recognize and understand the complexities of language learning and teaching both locally and globally.

Key words: Collaborative reflection, post-observation session, teacher supervision.

El objetivo de este trabajo es presentar diferentes roles de profesor supervisor según modelos distintos y destacar la importancia de diálogos colaborativos con apoyo de grabaciones de video. Para lograrlo, se muestran resultados de un estudio cualitativo desarrollado en un curso de formación de profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera en Brasil. Los resultados indicaron que la supervisión colaborativa fue eficiente frente a la adversidad de contextos educativos. Se concluyó que los estudiantes-profesores que observaron sus acciones pedagógicas a través de videos se volvieron más reflexivos y lograron autoevaluarse, ya que hacían un profundo análisis de su práctica. Con supervisión colaborativa, se alienta a futuros profesores a reconocer y comprender las complejidades de la enseñanza y aprendizaje local y globalmente.

Palabras clave: reflexión colaborativa, sesiones de post-observación, supervisión docente.

Introduction

Within the context of language teacher education, teaching practice has been analyzed from different perspectives. Traditional perspectives conceive it as training, that is, a teaching activity is a moment to exteriorize the knowledge and skills acquired by teachers, who should demonstrate efficiency when applying techniques and strategies in their language classrooms (Freeman, 2009).

Burns and Richards (2009), Richards (1998), Wallace (1991), Williams (2001), and Zeichner (2008) argue that categorizing professional teacher preparation as training reduces teacher education to the mere application of strategies and techniques created and sustained by external researchers who are distant from the needs and particularities of a determined educational context.

In reflective language teacher education, teaching practice occupies a relevant formative place because it is seen as one of the main scenarios for systematic observation, analysis, reflection, assessment, and action concerning language teaching and learning. In addition, it has become a context in which prospective teachers can reflect on their own practice, aiming at language teaching, learning optimization and continuous self-professional development. According to Gebhard (2009), other teaching practice objectives in initial teacher education include developing teachers' knowledge about school and classroom realities, improving teaching abilities and competences for professional practice, stimulating systematic observation and reflection about their pedagogical actions, and providing opportunities for future teachers to engage in collaborative projects.

Given that teaching practice is a relevant context for observation, analysis, and reflection, teacher supervision plays an important role in this process because it should be able to stimulate student teachers to reflect on their own practice if they take the leading role in problem solving and decision making (Burns & Richards, 2009). Alarcão, Leitão, and Roldão (2009) affirm that different supervision approaches are directly related to conceptions of teacher education. Because there are various models of language teacher supervision, it is relevant to distinguish supervision for developmental purposes, "which is often seen as collaborative model" (Young, 2009, p. 2), and that for evaluative reasons, which is usually associated with prescriptive approaches.

In this paper, I aim to present and discuss the roles of teacher supervisors according to different models of supervision, highlighting collaborative dialogue between supervisors and student teachers in post-observation sessions supported by video recordings based on results obtained in a qualitative study.

One of the goals of this investigation was to understand how future teachers evaluated their pedagogical actions and how they justified their decisions and solved problems in their teaching practice. In order to attain this goal, student teachers' classes were observed and video-recorded, and these recordings were used as input for post-observation reflective sessions with the researcher, who also played the role of a supervisor. It should be mentioned that for the purposes of this paper, only data involving class observations and post-observation sessions will be discussed because our main goal is to reflect on the collaborative dialogue between supervisors and student teachers when discussing their pedagogical actions during teaching practice in post-observation sessions enhanced by videotaped lessons.

The research data included teaching practice reflective journals, video-recorded class observations, and post-observation reflective sessions. Class recordings are commonly used in teacher supervision to supplement observations and to enrich post-observation conferences (Sewall, 2009). Based on Sewall's point of view, these recordings were used to support discussions and reflections between student teachers and their researcher/supervisor.

In the next sections, some relevant topics concerning teaching practice in language teacher education will be presented in order to discuss different models of supervision and supervisors' roles. Then, we will briefly describe the investigation design to examine information regarding its rationale, methodology, and the instruments used for data collection. After that, some of the collected data and results for student teachers' teaching practice and post-observation sessions will be discussed.

Teaching Practice in Pre-Service Language Teacher Education

In this section, we will present various authors and their conceptions of reflective teaching. Then, the purposes and characteristics of teaching practice in teacher education courses in Brazil will be briefly discussed.

Previous studies (Batista, 2007; Celani, 2000; Sturm, 2008; Vieira-Abrahão, 2001) have indicated that English as a foreign language (EFL) teacher education courses still struggle to coherently balance theory and practice in order to enable future teachers to reflect critically on their pedagogical decisions and to theorize from their own practice by conducting their own studies. As Kumaravadivelu (2006) argues, reflection and autonomy are key ways for teachers to become researchers in their own classrooms. When they recognize their potential to theorize from their own practice and practice what they theorize through observation, analysis, and evaluation, they become able to engage in continuous self-professional development.

According to Wallace (1991), Zeichner (2001), and Zeichner and Liston (1996), reflective teaching can promote the ability of teachers to use tools to critically analyze and initiate changes in educational contexts. As a consequence, teachers are "empowered with knowledge, skill, and autonomy" (Tudor, 2001, p. 23) to become engaged in their own professional development as well as active participants in decision making when they face the complexity of language teaching and learning.

We believe that teachers have conditions to solve problems regarding their educational practice, as Zeichner and Liston (1996) affirm. As stated by the authors, reflective teachers are capable of examining their own practice and recognizing intrinsic values attributed to their teaching in both institutional and cultural contexts.

The above-mentioned perspectives of reflective teaching will be taken into account to closely examine the school-based experience during pre-service teacher education courses. In our particular context, teaching practice is developed in public schools (Junior High and High Schools), and Brazilian educational legislation demands 400 hours of teaching practice including classroom observations, theoretical study in teacher education courses, and reports on teaching practice. The main objective of teaching practice in pre-service teacher education courses in Brazil is to insert future teachers into school contexts so they can observe and experience educational realities.

Bailey (2006) states, "teaching practice is a component of many professional preparation programs for teachers. It is predicated on the assumption that novice teachers need guided practice in learning how to teach" (p. 233). Normally, the student teacher is placed with an experienced teacher who teaches a particular subject in a school. This future teacher is also supervised by a supervisors and/or educators of the teacher education program based in the student's university.

For Hiebert, Morris, Berk, and Jansen (2007) the practicum experience is an opportunity to learn from teaching because student teachers have subject matter knowledge and analytical skills that allow them to analyze teaching and its effect on students' learning. Johnson (2009) argues that knowledge generated in practice teaching is organized around problems that emerge from practice and that are in contexts in which such problems are constructed. For this reason, analytical and reflective skills should be developed during pre-service courses so that future teachers are able to act autonomously in their classrooms and study their own practice (Kumaravadivelu, 2003).

This idea of local knowledge is similarly supported by Birch (2009), who conceives local and global knowledge as glocalized pedagogy that "honors the knowledge and experience of local teachers who are experts in the cultural and social resources for learning and the participants' openness to learning" (p. 134). According to the author, teachers should be empowered to be capable of looking at their own classrooms as a place to expand their practical and theoretical knowledge.

In order to meet these objectives, future teachers need to be stimulated to (re)construct their knowledge and to reflect on their classroom practices during teaching practice. The role of supervisors is crucial in this formative process to ensure that this school experience leads to professional development.

Given that the importance and relevance of teaching practice for initial teacher education have been made clear, the next section of this paper aims to present different language teacher supervision models. Then, supervisors' roles in teaching practice will be briefly discussed.

Language Teacher Supervision and Supervisors' Roles

In this section, we will discuss different supervision models and supervisors' roles in these models. Then, some relevant aspects of the use of videos of classroom teaching will be presented.

Before discussing teacher supervision models and supervisors' roles in teaching practice, it is important to present our comprehension of supervision. This term has many distinct definitions, generally borrowed from the fields of general education and business and industry (Bailey, 2006). According to Kilminster et al. (as cited in Muttar & Mohamed, 2013), in broad terms, supervision can be defined as the "provision of guidance and feedback on matters of personal, professional and educational development in the context of trainee's experience taking place" (p. 2).

In language teacher education, Wallace (1991) established two different categories, general supervision, which is concerned with administrative aspects, and clinical supervision, which regards formative issues. The latter can be separated into a prescriptive approach and collaborative approach. According to the author's descriptions, clinical supervision focuses on teaching and other classroom aspects, and "it implies a rejection of the applied science model and an acceptance of the reflective model of professional development" (Wallace, 1991, p. 108). He understands clinical supervision as an interactive session between a supervisor and a teacher with the purpose of discussing and analyzing previously observed classroom teaching in order to promote professional development. It is relevant to mention that clinical supervision might be implemented in a variety of ways and that it is understood differently by some authors; this will be discussed later in this section.

Bailey (2006) argues that language teacher supervision not only is concerned with positive aspects, such as helping language teachers achieve their professional development, but also includes less positive results such as providing negative feedback, ensuring that teachers adhere to program policies, and even firing them. Some of the supervisors' responsibilities might involve "visiting and evaluating other teachers, discussing their lesson with them, and making recommendations to them about what to continue and what to change" (Bailey, 2006, p. 3). However, these are not the only activities for which supervisors are responsible; their duties also include teaching courses and dealing with administrative tasks in teacher education programs.

According to Wallace (1991), a supervisor is "anyone who has ... the duty of monitoring and improving the quality of teaching" (p. 107) teachers in a given educational context. In addition, Gebhard (1990) states that supervisors are responsible for directing teachers' teaching, offering suggestions, modeling teaching, advising teachers, and evaluating teachers' teaching.

Sewall (2009) adds that supervisors also have to address another challenge because they play a dual role; they serve as mentors, guiding teachers, and as evaluators, assessing their teaching practice. Furthermore, the author states that the term "supervisor" has a hierarchical connotation because it carries the meaning of an expert and novice relationship. We strongly defend a genuine collaborative and reflective environment between supervisors and supervisees.2 From our point of view, to comprehend this supervisor and supervisee relationship as a hierarchical one can be threatening or even negative, and it might not be beneficial to teacher development (Kayaoglu, 2012).

In teaching practice, this hierarchical idea of placing student teachers with an experienced teacher to observe and learn can be seen as an illustration of the craft model previously discussed by Wallace (1991). The author explains that according to this model, "wisdom of the profession resides in an experienced professional practitioner: someone who is an expert in the practice of the craft" (p. 6), and it is expected that trainees learn by imitating the expert's techniques and instructions. It is noticeable that within this model of teaching practice, supervision tends to reside in prescriptive approaches.

There are various models of language teacher supervision; therefore, it is important to distinguish supervision for developmental and evaluative purposes. The former is generally seen as a reflective and collaborative model, and the latter is usually associated with prescriptive approaches (Young, 2009).

Bourke (2001) presents four different models of teacher supervision previously described by Tanner and Tanner (as cited in Bourke, 2001): inspectional, production, clinical, and developmental. According to the first model, supervisors are inspectors, and education is perceived as strict adherence to governmental policies, methods, and materials. The production model adopts a production-efficiency approach to education in which teachers are similar to factory workers who are responsible for preparing their students for institutional assessments. In the clinical model, a supervisor observes a lesson and discusses teaching events in a face-to-face interaction with the teacher to analyze teaching behaviors and activities. This model usually involves pre-observation conferences, and the actual observations, analysis, and strategies to be used in supervision conferences and post-conference analysis. However, there are some problems with this model because it assumes that elements of teaching events can be identified and classified by observing student teachers, and it also focuses on classroom instruction, ignoring curricular development and educational planning. According to this model, teachers should follow the instructions and techniques to be applied in their language classrooms in order to be considered efficient teachers.

The fourth model—the developmental model—is defined as a cooperative problem-solving process, aiming at stimulating discovery, inquiry, and problem solving. It goes beyond specific teaching points and provides a creative and collaborative learning environment.

Bailey (2009) presents some other models of supervision based on Freeman's models of intervention, which include the directive, nondirective, and alternative options (Freeman as cited in Bailey, 2009). First, it is important to mention that Freeman(1990) cites supervision as intervention, assuming that it presupposes that future teachers can benefit from the input and perceptions of a teacher educator (which is what we understand as feedback). According to the author, in directive forms of supervision, the teacher educator makes comments on student teachers' practice and gives them suggestions to be implemented in their classrooms. The main objective is to improve the teacher's performance according to the supervisor's criteria or to a (pre)conceived lesson structure. In the alternative form of intervention, the teacher educator selects an issue from classroom teaching to be discussed with student teachers and gives them some alternatives to solve this problem in their teaching. The purpose of this model is to improve student teachers' decision making and to develop their ability to articulate their knowledge and experience by providing informed choices. Then, in non-directive supervision, the teacher educator gives student teachers the opportunity to make their own choices without inferring or directing them so that the student teachers can find their own solutions. The model's main goal is to "provide the student-teacher with a forum to clarify perceptions of what he or she is doing in teaching and for the educator to fully understand" (Freeman, 1990, p. 112). This does not necessarily mean that the teacher educator has to accept future teachers' points of view or to agree with them.

Gebhard (1990) expands these models proposed by Freeman (1990) by including another three models: collaborative supervision, creative supervision and self-explorative supervision. In the collaborative model, the supervisor and the teacher work together to find a hypothesis and to identify teaching and learning problems. The supervisor participates in student teachers' decisions, trying to establish a sharing relationship, instead of directing the student teachers. The creative supervision model is defined as the combination of the other four models (directive, nondirective, alternatives, and collaborative) to approach teachers' specific needs in their educational context. It presupposes freedom and creativity because it allows for a combination of supervisory models, shifting supervisory responsibilities from the supervisor to other sources because it involves an application of insights from other fields not found in any of the other models. Additionally, the self-explorative model can be interpreted as an extension of the creative supervision model because it allows both teachers and supervisors to gain self-awareness through observation and exploration, as they both "explore teaching through observation of their own and other's teaching in order to gain an awareness of teaching behaviors and their consequences, as well as to generate alternative ways to teach" (Gebhard, 1990, p. 163).

Regardless of the supervision model adopted in teacher education programs, supervisors should understand that these interactions might influence and shape teachers' thinking and behavior, as argued by Cheng and Cheng (2013). As teacher educators and researchers, we should bear in mind that teachers perceive supervision differently because their experiences are influenced by their personal values and beliefs related to language teaching. We strongly believe that due to these factors, teachers might benefit distinctly from these interactions.

Within these different models of supervision, according to Chamberlin (as cited in Young, 2009), an effective supervisor should develop a clear program to improve student teachers' performance and to nurture best practices through a process of reflective questioning. We defend that the role of the supervisor is to support teachers' pedagogical knowledge construction through collaborative discussions of their pedagogical practice.

These discussions can be enriched with class video recordings, which can be used as a tool to supplement post-observation sessions, as argued by Sewall (2009) and Sherin and van Es (2005). Historically, videos have been used in teacher education for different purposes since the 1960s, including micro-teaching, interaction analysis, video-based cases, and video club meetings (Sherin & van Es, 2005). Among these different uses and purposes of videos, one feature stands out: they provide easy access to classroom interactions and events that would be impossible to remember without such a tool.

Sewall (2009) recommends that videotaped lessons be analyzed by teachers and supervisors cooperatively in order to be an effective instrument for pedagogical development. The author also defends the relevance of using videos in post-observation sessions because they allow for a more focused discussion of the lesson, as future teachers are able to revisit specific details of their teaching.

In the next sections, the rationale and the research design will be briefly presented in order to discuss and analyze the interaction between teachers and supervisors in collaborative post-observation sessions with the support of video recordings of teaching practice.

Rationale

This paper is mainly concerned with language teacher supervision, as it proposes the discussion of teacher supervisors' roles in different supervision models of teaching practice, emphasizing the importance of the collaborative dialogue between teachers and supervisors supported by video-recorded classes in post-observation sessions.

Another indirect research objective we expect to address in this study is reflecting on the problem of teacher supervision concerning "what goes on during and what happens afterwards" these interactions, as it is rarely reported and analyzed, as indicated by Cheng and Cheng (2013, p. 4). Often, teachers receive feedback from their supervisors, indicating the need for changes in their classroom practices; however, they find difficulty in implementing such changes.

Bearing this background in mind, we agree with Vieira's (2009) affirmations on the importance of pedagogical supervision based on a critical pedagogy view. For this author, through this critical perspective on teaching practice and supervision, it is possible to transform pedagogical action, making it more conscious and deliberative and, thus, more susceptible to change, allowing for the recognition of its complexity and uncertainty. Therefore, the main goal of student teachers' pedagogical supervision is to support and help them to become supervisors of their own practice, supplying them with the will and ability to (re)conceptualize their pedagogical knowledge and to participate, individually and/or collectively, in the (re)construction of school pedagogy.

We believe this is a form by which future teachers could be stimulated in their initial teacher education courses to become investigators of their own pedagogical practice. By studying their own classrooms, they can improve their abilities to (re)construct their knowledge about language learning and teaching process, aiming at a better comprehension of the complexities involved in this process in real school situations.

By the same token, Pimenta (2009) agrees with this relevance of teaching practice in teacher education, as she considers teachers' practice and school pedagogy to be the starting and ending points of initial teacher education courses. Future teachers should be stimulated to "reframe formative processes from the reconsideration of the knowledge needed to teach, putting pedagogical and school teaching practice as an object of analysis" (p. 17 [trans.]).

However, some initial teacher education courses tend to fail in efficiently preparing teachers for different educational realities, and as a consequence, the professionals certified in these institutions begin working in school contexts without knowing how to address obstacles they find in their classrooms, as Batista (2007) concluded in his research on teaching practice and teacher education.

According to Zeichner (2003), the lack of attention to teaching in social contexts in addition to reflective practice taken as an individual action encourage teachers to think of their problems as "exclusively theirs, with no relation to other teachers' problems or no connection to educational systems" (p. 45 [trans.]). Thus, teachers are unable to engage in a critical analysis of school situations in which they live, as they only worry about their individual flaws.

This problematic scenario may have its origins in teacher education models in which there is a prevalence of transmission processes concerning knowledge production and recurrence of theoretical and practical dissociation (Lenoir, 2006). Therefore, we support the idea that initial teacher education should contribute to the development of a personalized reflective practice, appraising not only positive aspects but also small unsuccessful actions in everyday school practice.

Investigation Design and Methods

The goal of the main study partially described here was to discuss the complexity of the pedagogical knowledge (re)construction process, attempting to understand prospective teachers' pedagogical strategies used to cope with problems in their teaching practice. Bearing this in mind, the objective of this paper is to discuss part of the collected data focusing on different supervisors' roles in distinct models of supervision and to reflect on the collaborative dialogue between teachers and supervisors in post-observation sessions supported by video recordings. Therefore, the main research design will be briefly presented, but only data concerning language teacher supervision, class recordings, and post-observation sessions focusing on the collaborative and reflective interactions between the researcher/supervisor and student teachers will be examined.

The investigated context was a five-year Initial Teacher Education Course offered at night by a public university located in the state of Sao Paulo. The subjects offered to future English teachers aimed at the construction of communicative competence with the development of oral and written skills and the understanding of constituent elements of language teaching and learning. This course study was executed in teaching practice classes, which focused on the discussion, reflection, and consolidation of theories and variables regarding foreign language teaching and learning. According to Brazilian educational legislation for teacher education courses, teaching practice should be completed in 400 hours through different activities that normally include the observation of an experienced teacher in a real school context, future teachers' teaching practice, theoretical and practical classes at a university, and the elaboration of reflective reports about this experience supervised by a teacher educator. The participants of the main study were six student teachers (of both genders and ranging from 20 to 24 years old) and the teacher educator, but for the purposes of this paper, interaction excerpts only with two future teachers will be presented.

Student teachers answered a questionnaire in the beginning of the study. Considering their previous language learning experiences, their responses revealed that their years of study of the English language ranged from two to eight years, and learning contexts covered mainly language schools and private tutoring. Only one student had previous formal contact with the English language, which occurred in public school. Of these six student teachers, four had previous English teaching experience, and the other two had Portuguese language teaching experience at the time of the data collection.

The teacher educator has a degree in Literature (Portuguese and English), as well as an MS and a PhD in Linguistics, and he has taught Teaching Practice in the investigated teacher education course since 2002. His research fields include English and Portuguese teaching and learning and initial and continuing language teacher education.

With the objective of supporting prospective teachers' language learning and their construction of teaching knowledge through collaborative discussions of their pedagogical practice, class video recordings were used in teacher supervision to supplement observations and to enrich post-observation sessions. By using videos, pre-service teachers were provided with opportunities to observe their pedagogical activities and to become more reflective, as they could analyze their own practice more deeply. The researcher played the roles of teacher supervisor and teacher educator because she observed and video-recorded student teachers' classes and provided feedback in collaborative and reflective post-observation sessions.

This investigation can be characterized as qualitative (Erickson, 1991; Larsen-Freeman & Long, 1991) because it emphasizes the description and analysis of events in a foreign language teacher education course, focusing on the meanings of those events for the participants (student teachers, teacher-educator, and teacher education researcher). This study can also be described as longitudinal because data collection was completed during two semesters in 2008 and 2009.

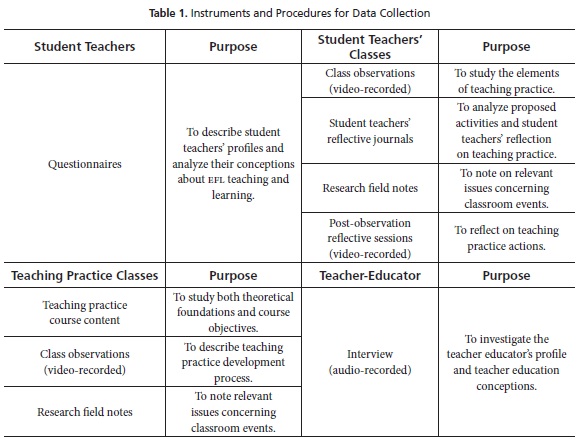

To guarantee the validity and reliability of this investigation, data collection and analysis were based in the use of the instruments and procedures shown in Table 1.

Discussion

The primary sources of information for this study were student teachers' class observations and recordings, post-observation reflective sessions, and reflective journals. For their teaching practice, future teachers taught EFL classes in pairs in regular schools (Junior High and High School). First, their classes were observed by the researcher/supervisor and video-recorded, and copies of the recordings were given to the student teachers so they could watch their class with the teacher educator and highlight interesting aspects of their teaching. The researcher/supervisor also chose relevant excerpts from their classes to be analyzed and discussed in post-observation sessions, which were also video-recorded. These sessions took place in the university context a few days after the class was observed by the teacher. To initiate the discussion, the researcher/supervisor posed questions about prospective teachers' impressions of the recorded class, indicating both positive and negative aspects of their lessons. Post-observation sessions were mainly concerned with the reflection on their pedagogical practice in order to investigate student teachers' ability to identify and to solve problems faced in their classroom practice. The main topics discussed with student teachers involved teaching approaches and procedures, teachers' and students' roles, grammar instruction, vocabulary teaching, coherence between activities and teaching objectives, and self-evaluation.

In one of these post-observation sessions, two future teachers, Henry and Fred,3 mentioned after watching their first class recordings that their classroom procedures were mainly ruled by grammar-translation techniques and that their activities were teacher-centered. They were surprised to see that they were reproducing teaching models they did not believe in or support, as they realized that their pedagogical discourse diverged from their classroom practices. These future teachers concluded that having the opportunity to watch their classes and to reflect on their own practice helped them identify and solve pedagogical problems in their classrooms.

The example of these two student teachers confirms Johnson's (2009) assumption that maintaining these types of dialogue and reflection with teachers makes them actively link theoretical knowledge to their experiential knowledge, stimulating them to reorganize their pedagogical knowledge as they create new forms of interpreting their classroom practice.

In the first classes taught by Henry and Fred, the proposed activities were teacher-centered, and students performed them individually. Vocabulary building was based on lists and translations, and grammar instruction was ruled by traditional perspectives because they conceived grammar structure as an object to be explicitly presented and decoded (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004), as we can see in the excerpts below in which student teachers corrected grammar-focused exercises:

Excerpt 1

Fred: He's going to...?

Student: Wash his hands

Fred: His hands, as mãos dele (translation in Portuguese), right? (Class 1)

Excerpt 2

Fred: "My" would be what kind of pronoun? Can you tell me?

Student: Possessive?

Fred: Possessive, right? (Class 1)

Bearing these actions and procedures in mind, during their first post-observation sessions, the student teachers mentioned the following issues:

Excerpt 3

Fred: One of the things I think is that the class was not dynamic, which is a negative aspect. The whole class, we stood there talking, practically just talking.

Researcher/Supervisor: And what do you think of that?

Fred: I think that because of the theme and the varied student levels, I think it's hard to work with other forms, but I think it would be positive to try to change something.

Researcher/Supervisor: What would you change?

Fred: I think that there must be reading, but I think we have to try to do it a little bit more dynamically. I don't know, I think we could try to work with reading in a different way...maybe give students an activity that they would have to work in pairs or in groups, so they could work alone, helping one another, then I think it would be more dynamic for them.

Henry: Oh, I think it would be better.

Fred: They would know each other a bit more and I think that they are still too shy and it would help in classroom dynamics. (Post-Observation Session 1)

It was interesting to notice that Henry and Fred perceived "something wrong" in their lessons, as they commented that the lessons needed to be more dynamic. The proposed activity to place students in pairs or in groups would make their lessons more student centered and would favor students' interaction. In their next lessons, they implemented these changes, so the activities were performed in pairs and in groups and focused on reading and discussing a text using reading strategies. Students had to try to solve the comprehension questions on their own without using a dictionary. To correct the activity, the student teachers suggested that students check their classmates' answers, using peer correction instead of teacher correction.

In the second post-observation session, the student teachers compared their first lessons to the activities proposed and the changes they implemented:

Excerpt 4

Henry: We changed our view of our students, we trusted them and we did one activity.

Fred: We did one activity in which they had to do it on their own, without our help, because we were bringing activities and correcting them together with students, reading with them, teaching grammar and such ... so, we proposed an activity with comic strips so they could do it on their own to give them more autonomy that we detected we were not favoring.

Researcher/Supervisor: And what did you think of this activity?

Fred: I think that the result was good. First, because they had contact with something different from what we were doing, translating word by word, which was something we didn't want to do, but we were doing ... Maybe it wasn't perfect, but there was an improvement, an evolution ... and students started to participate more, and I think they are feeling more confident. (Post-Observation Session 2)

According to Henry and Fred, their new activities gave more autonomy and confidence to their students, who participated more actively in their lessons. They criticized their teaching performance in their first lessons, and they believed the implemented changes brought about more positive results. At the beginning of their teaching practice experience, their lessons were structured on teacher presentation and explanation, students' activities, and teacher correction. After the collaborative and reflective post-observation sessions, the activities they proposed in their classrooms involved discussions in pairs and in groups and peer correction.

In teaching practice classes at the university, the student teachers mentioned that due to the heterogeneity of students' language levels, they did not know how to proceed, and because of this difficulty, they ended up proposing teacher-centered activities. In his reflective journal, Fred compared the experience of observing an experienced teacher and his own teaching:

Excerpt 5

I could notice how hard it is to (self)reflect on our own pedagogical practice. It is much easier to observe and tell where the other teacher was wrong, than to envision where we were wrong. Even though it is hard, this should be an exercise that we should always do, because it helps us improve our work as teachers. (Reflective Journal 1)

It can be seen that Fred considered self-evaluation and reflection on his own practice as a necessary activity for his professional development because it can improve his performance as a teacher. He emphasized self-reflection on his teaching activities in the classroom as a way to (re)construct his own practice, fostering continuous professional development.

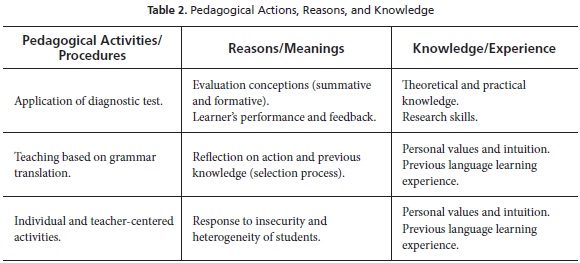

Table 2 summarizes student teachers' pedagogical activities and procedures during their class observations and feedback sessions, indicating the reasons for their actions with our interpretation of possible sources of previous knowledge to address their classroom needs and teaching problems.

In order to justify their pedagogical actions and procedures in the language classroom, the student teachers were influenced by their personal values and intuition about language teaching and learning, previous language learning experiences, theoretical and practical knowledge, and research skills. These elements relate to different levels of reflection. When based on informal knowledge constructed by experiences and intuition about language teaching and learning, future teachers are oriented by practical reflection (Liberali, 2008). However, when they present explanations based on research skills and theoretical and practical knowledge constructed throughout their teacher education course, they are guided by critical reflection.

We support the argument that teachers need both theoretical and practical knowledge and research skills to engage in continuous professional development and in the production of knowledge about the language classroom. This way, teachers will be able to question education activities and educational contexts, oriented by critical reflection (Kumaravadivelu, 2006).

Another interesting aspect regarding these reflective and collaborative post-observation sessions enriched by video-recorded lessons is that future teachers actively participated in the lesson discussion and analysis. They contributed to the majority of the reflective comments, which shows their development of autonomy, similarly to Sewall's results (2009). In these sessions, both supervisors and supervisees had the chance to highlight relevant aspects to be collaboratively discussed and analyzed, which favored equal dialogues without hierarchical connotations between the expert and novice teacher, as one of the participants mentioned in his reflective journal:

Excerpt 6

It is important to emphasize that what helped us in these reflections was the participation of the researcher in our teaching practice activities, because she discussed with us throughout our course how our classes were taught. (Fred's Reflective Journal 1)

The results indicated that pre-service teachers with opportunities to observe their pedagogical actions through videos were able to become more reflective and to provide deeper analysis of their practice in collaborative post-observation sessions. It was also observed that due to the use of videos, student teachers could distance themselves from their own practice, which contributed to their analysis of and reflection on their pedagogical actions.

Conclusions

In this section, we will present the conclusions of this study, pointing out some positive aspects of the collaborative and reflective dialogues generated in post-observation sessions with the use of video recordings in teaching practice. Then, some limitations of this study will be presented.

Through self-evaluation and reflection in video-supported post-observation sessions, future teachers were able to analyze their pedagogical practice, (re)constructing it to favor their students' language-learning process and contributing to their professional development as educators. They tried to understand the reasons behind their pedagogical actions, indicating possible ways to change language teaching and learning situations according to the needs of their educational contexts.

As both teachers and supervisors collaboratively analyzed class video recordings, an equal and supportive relationship between them could be developed. Furthermore, by viewing their lessons, teachers were able to experience a different reflective practice, as they developed new ways to examine their classrooms and to critically self-evaluate their pedagogical actions. During the reflective and collaborative post-observation sessions, the student teachers established connections with theoretical course content, previous learning and teaching experiences, and their personal knowledge when analyzing their pedagogical actions in videotaped lessons.

Through collaborative supervision, future teachers were able to engage with their own professional development and become active participants in decision making regarding the complexity of language teaching and learning. They could also investigate their own pedagogical practice, aiming at a better comprehension of the language-teaching process in real school situations, as they were able to look at their own classrooms as a place to expand their practical and theoretical knowledge.

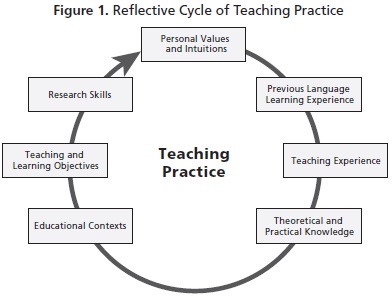

Figure 1 summarizes the different dimensions involved in student teachers' pedagogical knowledge (re)construction after video-supported post-observation sessions.

During the sessions, it was possible to note that student teachers who observed their pedagogical actions through videos became more reflective and self-evaluative, developing their investigation skills, as they identified problems and searched for answers. When searching for these answers, they were influenced by their previous language-learning and teaching experiences and by theoretical and practical knowledge concerning language teaching and learning. It is important to recognize that this knowledge is viewed differently according to their personal values and intuitions of what works in an EFL classroom. We believe future teachers also considered their learners' objectives, taking variables of educational contexts into account when implementing changes in their teaching practice.

Thus, we conclude that with collaborative supervision, teacher candidates can be encouraged to identify and understand the complexities of language learning and teaching locally and globally, instead of formulating technical and universal solutions that might not cater to the specific needs of different educational contexts.

One of the limitations of this study was that the researcher/supervisor did not observe prospective teachers' classes over an entire school year and that other relevant aspects of language teaching could have been discussed with more collaborative and reflective sessions and videotaped lesson debriefings. It is also important to implement these practices in other contexts of teacher supervision, involving more teachers and supervisors to analyze the similarities and differences of the results obtained. In addition, all classes were observed and videotaped by the researcher/supervisors. It would be interesting to suggest that teachers themselves record their lessons, delegating them more auto-nomy in this process.

Collaborative supervision through videos of classroom teaching can be implemented in other teacher education programs, but the particularities of those contexts should be analyzed in order to make this suggestion feasible for both supervisors and student teachers because it demands extra time from teaching practice classes. Another important aspect to consider in its implementation is related to teacher education course curricula, which need to guarantee formative spaces for the use of video programs aiming at teachers' professional development.

Furthermore, supervisors should be able to develop strategies to improve student teachers' teaching practice and nurture reflective practice. They are also expected to support teachers' language learning and teaching knowledge construction through collaborative reflections on their pedagogical practice. Because of these responsibilities, they should be highly qualified and experienced, as they need to be knowledgeable about teacher supervision, constructive feedback and collaborative projects in teacher education.

1This article is based on the PhD study entitled, "The process of pedagogical practice (re)construction of pre-service English language teachers," which was supervised by Prof. Dr. Maria Helena Vieira-Abrahão and financed by FAPESP (number 08/53911-2).

2The term supervisee is used by Ho (2003), and it refers to future language teachers supervised by a teacher educator.

3Pseudonyms created by the researcher.

References

Alarcão, I., Leitão, A., & Roldão, M. C. (2009). Prática pedagógica supervisionada e feedback formativo co-construtivo [Supervised pedagogical practice and formative-constructive feedback]. Revista Brasileira de Formação de Professores, 1(3), 2-29. [ Links ]

Bailey, K. M. (2006). Language teacher supervision: A case-based approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667329. [ Links ]

Bailey. K. M. (2009). Language teacher supervision. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 269-278). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Batista, L. O. (2007). A disciplina de prática de ensino de língua inglesa vista por professores recém-formados [English teaching practice from the novice teachers' perspectives]. Contexturas: Ensino Crítico de Língua Inglesa, 12, 75-90. [ Links ]

Birch, B. M. (2009). The English language teacher in global civil society. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bourke, J. M. (2001). The role of the TP TESL Supervisor. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 27(1), 63-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02607470120042546. [ Links ]

Burns, A., & Richards, J. C. (2009). Second language teacher education. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 1-8). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Celani, M. A. A. (2000). A relevância da linguística aplicada na formulação de uma política educacional Brasileira [The relevance of applied linguistics in Brazilian educational policy]. In M. B. M. Fortkamp & L. M. Tomitch (Eds.), Aspectos da linguística aplicada: estudos em homenagem ao professor Hilário Inácio Bohn (pp. 17-32). Florianópolis, BR: Editora Insular. [ Links ]

Cheng, C. W. Y., & Cheng, Y. S. (2013). The supervisory process of EFL teachers: A case study. TESL-EJ, 17(1). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume17/ej65/ej65a1/. [ Links ]

Erickson, F. (1991). Advantages and disadvantages of qualitative research design on foreign language research. In B. F. Freed (Ed.), Foreign language acquisition research and the classroom (pp. 338-353). Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (1990). Intervening in practice teaching. In J. C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 103-117). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (2009). The scope of second language teacher education. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 11-19). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gebhard, J. G. (1990). Models of supervision: Choices. In J. C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 156-166). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gebhard, J. G. (2009). The practicum. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 250-258). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hiebert, J., Morris, A. K., Berk, D., & Jansen, A. (2007). Preparing teachers to learn from teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 47-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022487106295726. [ Links ]

Ho, B. (2003). Time management of final year undergraduate English projects: Supervisees' and the supervisor's coping strategies. System, 31(2), 231-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(03)00022-8. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Trends in second language teacher education. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 20-29). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kayaoglu, M. N. (2012). Dictating or facilitating: The supervisory process for language teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(10), 103-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n10.4. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Long, M. H. (1991). Second language acquisition research methodology. In D. Larsen-Freeman & M. H. Long (Eds.), An introduction to second language acquisition research (pp. 10-51). New York, NY: Longman. [ Links ]

Lenoir, Y. (2006). Pesquisar e formar: repensar o lugar e a função da prática de ensino [Research and education: Rethinking the position and function of teaching practices]. Educação e Sociedade, 27(97), 1299-1325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302006000400011. [ Links ]

Liberali, F. C. (2008). Formação crítica de educadores: questões fundamentais [Critical education for educators: Fundamental questions]. Taubaté, BR: Cabral Editora. [ Links ]

Muttar, S. S., & Mohamed, H. K. (2013). The role of English language supervisors as perceived by English language teachers. Misan Journal for Academic Studies, 12(22), 1-12. Retrieved from http://misan-jas.com/pdf%2022/12%20%20%2022.pdf. [ Links ]

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2004). Current developments in research on the teaching of grammar. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 126-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190504000066. [ Links ]

Pimenta, S. G. (2009). Formação de professores: identidade e saberes da docência [Teacher education: Identity and teaching knowledge]. In S. G. Pimenta (Org.), Saberes pedagógicos e atividade docente (pp. 15-34). São Paulo, BR: Editora Cortez. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C. (1998). Beyond training. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sewall, M. (2009). Transforming supervision: Using video elicitation to support preservice teacher-directed reflective conversations. Issues in Teacher Education, 18(2), 11-30. Retrieved from http://www-tep.ucsd.edu/_files/edd/05sewall.pdf. [ Links ]

Sherin, M. G., & van Es, E. A. (2005). Using video to support teachers' ability to notice classroom interactions. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13(3), 475-491. Retrieved from http://www.professional-vision.org/pdfs/SherinvanEs_JTATE.pdf. [ Links ]

Sturm, L. (2008). A pesquisa-ação e a formação teórico-crítica de professores de línguas estrangeiras [Action research and critical foreign language teacher education]. In G. Gil & M. H. Vieira-Abrahão (Eds.), Educação de professores de línguas: os desafios do formador (pp. 339-350). Campinas, BR: Pontes. [ Links ]

Tudor, I. (2001). The dynamics of the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Vieira, F. (2009). Para uma visão transformadora da supervisão pedagógica [Towards a transformative visiono of pedagogical supervision]. Educação e Sociedade, 29(105), 197-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302009000100010. [ Links ]

Vieira-Abrahão, M. H. (2001). Formação acadêmica e a iniciação profissional do professor de línguas: um estudo da relação teoria e prática [Academic education and professional initiation of language teachers: A study of the relationship between theory and practice]. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 37, 61-81. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Williams, M. (2001). Learning teaching: A social constructivist approach-theory and practice or theory with practice? In, H. Trappes-Lomax & I. McGrath (Eds.), Theory in language teacher education (pp. 11-20). Essex, UK: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Young, S. (2009). Supporting and supervising teachers working with adults learning English. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/resources/supporting.html. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. M. (2001). Educating reflective teachers for learner-centered education: Possibilities and contradictions. Proceedings of 16o Encontro Nacional de Professores Universitários de Língua Inglesa. Londrina, Brazil. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. M. (2003). Formando professores reflexivos para a educação centrada no aluno: possibilidades e contradições [Educating reflective teachers for learner-centered education: Possibilities and contradictions]. In R. L. L. Barbosa (Org.), Formação de professores: desafios e perspectivas (pp. 35-55). São Paulo, BR: Editora Unesp. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. M. (2008). Uma análise crítica sobre a "reflexão" como conceito estruturante na formação docente [A critical analysis of reflection as a goal for teacher education]. Educação e Sociedade, 29(103), 535-554. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302008000200012. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. M., & Liston, D. P. (1996). Reflective teaching: An introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

About the Author

Sandra Mari Kaneko-Marques is an English Professor at UNESP-FCL-Araraquara (Brazil) and holds a degree in English, an MA in Linguistics and a PhD in Applied Linguistics. She has experience as an English teacher in high schools, language institutes, and universities. Her research areas are teacher education, language teaching, and English for academic purposes.