Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 140 million births occur annually since 2018 1. This organization defines normal childbirth as an event with an uncertain onset that proceeds without complications provided that, after delivery, the mother-child pair is in good general condition 2-4. Vaginal birth is defined as "a birth without medical intervention that usually involves relaxation techniques" 5. The WHO promotes vaginal birth as a means of ending pregnancy even in the presence of a SARS-CoV-2 infection 6.

In this sense, humanized birth refers to a childbirth experience that occurs under normal conditions, prioritizing the opinions and needs of the woman and her accompanying family members during labor and the postpartum period, working as a team with healthcare personnel to make it a satisfying, positive, and unforgettable experience where human dignity prevails 4,7. The Latin American and Caribbean Network promotes the humanization of birth and childbirth (REL-ACAHUPAN); this network was created at the Ceará Brazil Congress and focuses on information and promotion actions 8. In Colombia, Law 2244 of 2022 9 ensures humanized childbirth care, promoting in women and their families the ability to decide and approach pregnancy to maintain the well-being of the mother-child pair 10, positively impacting the woman, her family, and society as a whole.

The healthcare team has the responsibility to provide comprehensive care to the mother-child pair, respect the autonomy, the family's environment, and sociocultural characteristics, avoiding unnecessary medical and pharmacological actions during labor to favor appropriate therapeutic actions according to their needs 11,12. The WHO identifies mistreatment, negligence, or lack of respect during childbirth as a violation of women's reproductive rights 3. The inappropriate or excessive use of procedures and technologies during childbirth can lead to iatrogenesis and obstetric violence, rather than ensuring safety 13,14, characterized by physical, verbal, and psychological harm, as well as negligence, often associated with a disproportionate number of cesarean sections, episiotomies, and even the use of forceps 15,16.

In light of the aforementioned, this exploration of women's experiences during vaginal childbirth was conducted to generate valid knowledge for professionals and health institutions interested in contributing to improving comprehensive care, promoting the humanization of childbirth, and reducing obstetric violence. A literature review was proposed to characterize the scientific evidence related to women's experiences during vaginal childbirth care.

Materials and Methods

An integrative review was conducted following Cooper's methodology 17,18: I) problem identification; II) literature search; III) data evaluation; IV) data analysis, and V) presentation and synthesis of data into thematic units. The research question was: What scientific evidence is available related to women's experiences during vaginal childbirth care reported in the period between 2010-2023?

Search Strategy

The search was conducted in six bibliographic databases: Cochrane, PubMed, Science Direct, Springer, Scopus, and Cinahl. The health sciences descriptors 19 used were: "Natural Childbirth", "Humanizing Delivery", "Humanization of Assistance", "Obstetric Violence", "Qualitative Research" and the Boolean operators AND and OR; the search equation was adjusted in each database.

Data evaluation complied with the following criteria: Qualitative full-text articles on women's experiences with vaginal childbirth in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, limited to the period 20102023 with a score of 8 or higher according to the Spanish Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASPe) 20.

The included articles were analyzed, the extracted data were compared, and similar data were classified and grouped; themes were organized to facilitate the process of analysis and synthesis. The analysis was conducted using the proposal of Miles and Huberman 18,21: data reduction, data visualization, data comparison, conclusion drawing, and verification.

Table 1 Search Equations in the Different Databases

| Database | Search equation |

|---|---|

| Cochrane: 132 articles | “Natural Childbirth” OR “Humanizing Delivery” OR “Humanization of Assistance” OR “Obstetric Violence” AND “Qualitative research” |

| PubMed: 54 articles | Search: “Natural Childbirth” OR “Humanizing Delivery” OR “Humanization of Assistance” OR “Obstetric Violence” AND “Qualitative research” Filters: Free full text, Full text, English, Portuguese, Spanish, from 2010 - 2023 |

| Cinahl: 254 articles | “Natural Childbirth” OR “Humanizing Delivery” OR “Humanization of Assistance” OR “Obstetric Violence” AND “Qualitative research” Limiters - Full text; Publication date: 20100101-20231231; Hidden NetLibrary Holdings Expanders - Apply Subject Equivalents Search Modes - Boolean/Phrase |

| Scopus: 91 articles | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Natural Childbirth” OR “Humanizing Delivery” OR “Humanization of Assistance” OR “Obstetric Violence” AND “Qualitative research “AND PUBYEAR > 2009 AND PUBYEAR < 2023 AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Portuguese”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Spanish”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE , “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO ( OA , “all” )) |

| Springer: 85 articles | “Natural Childbirth” OR “Humanizing Delivery” OR “Humanization of Assistance” OR “Obstetric Violence” AND “Qualitative research” within English Article 2010 - 2023 |

| ScienceDirect: 181 articles | “Natural Childbirth” OR “Humanizing Delivery” OR “Humanization of Assistance” OR “Obstetric Violence” AND “Qualitative research” |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

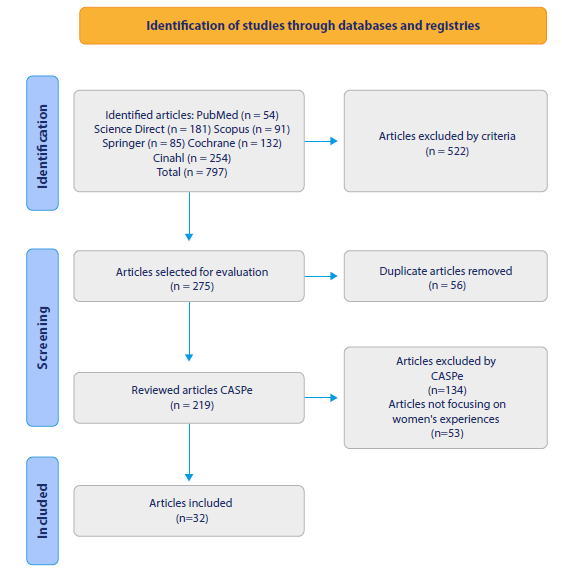

The integrative review found 797 articles, which were reviewed by title and abstract; 522 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 56 were excluded due to duplication. A total of 219 articles were submitted for quality assessment using the CASPe and 85 articles were included for analysis if they scored 8 or higher, of which 53 articles that did not focus on women's experiences were excluded, leaving only 32 documents that did meet the inclusion criteria for analysis.

Source: Elaborated by the authors, using the PRISMA 2020 diagram.

Figure 1 Search and Evaluation of Data Obtained in the Integrative Review

The thematic analysis was performed with 32 selected articles; 603 units of meanings were obtained, which were consolidated and grouped into six thematic units, allowing the deepening of the meaning of the childbirth experience.

Results

Table 2 Characterization of the Articles Included in the Thematic Units

| Title | Authors | Database | Thematic unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exploring factors contributing to the mistreatment of women during childbirth in the West Bank, Palestine 22 | Ibtesam Medhat Mohamad Dwekat; Tengku Alina Tengku Ismail; Mohd Ismail Ibrahim; Farid Ghrayeb. | PubMed | Micro-aggressions and macro- impacts: childbirth: Between pain and fear |

| 2. A qualitative study of women’s experiences with obstetric violence during childbirth in Turkey 23 | Nihal Avcı; Meltem Mecdi Kaydırak. | ||

| 3. Motivations for planned home birth: exploratory descriptive study 24 | Thamires Fernandes Cardoso da Silva Rodrigues; Lorena Viccentine Coutinho Monteschio; Eliana Cismer; Maria das Neves Decesaro; Deise Serafim; Sonia Silva Marcon. | Cinahl | |

| 4. ‘Safe’, yet violent? Women’s experiences with obstetric violence during hospital births in rural Northeast India 25 | Sreeparna Chattopadhyay; Arima MishraB; Suraj Jacob. | ||

| 5. Woman’s empowerment in planned childbirth at home 26 | Joanne de Paula Nascimento; Diego Vieira de Mattos; Maria Eliane Liégio Matão; Cleusa Alves Martins; Paula Ávila Moraes. | ||

| 6. Episiotomy: Feelings experienced by mothers 27 | Janaina Pacheco Villela; Isabella de Souza Ramos da Silva; Elizabeth Rose Costa Martín; Raquel Concepción de Almeida Ramos; Cristiane María Amorim Costa; Thelma Spindola. | Scopus | Acting with respect: Childbirth as a natural process |

| 7. The pregnancy and delivery process among Kaingang women 28 | Aline Cardoso Machado Moliterno; Ana Carla Borghi; Larissa Helena de Souza Freire Orlandi; rosangelacelia faustino; Deise Seraphim; Ligia Carreira. | ||

| 8. Humanization practices in the parturitive course from the perspective of puerperae and nurse-midwives 29 | Mariana Silveira Leal; Rita de Cassia Rocha Moreira; María Lucía Silva Servo; Tania Christiane Ferreira Bispo. | ||

| 9. Planned home birth assisted by a midwife nurse: meanings, experiences and motivation for this choice 30 | María Aparecida Baggio; Camila Girardi; Taís Regina Schapko; Maycon Hoffmann Cheffe. | Cinahl | |

| 10. “When helpers hurt”: Women’s and midwives’ stories of obstetric violence in state health institutions, Colombo district, Sri Lanka 31 | Dinusha Perera; Ragnhild Lund, Katarina Swahnberg; Berit Schei; Jennifer J. Infanti. | Springer | Silencing, enduring, and bearing |

| 11. Obstetric violence in the context of labor and birth 32 | Diego Pereira Rodrigues; Valdecyr Herdy Alves; Raquel Santana Vieira; Diva Cristina Morett Romano Leão; Enimar de Paula; Mariana Machado Pimentel. | Cinahl | |

| 12. Perception of normal delivery puerperal women on obstetric violence 33 | Tayná de Paiva Marques Carvalho; Carla Luzia França Araújo. | ||

| 13. Conventional practices of childbirth and obstetric violence under the perspective of puerperal women 34 | Vanuza Silva Campos; Ariane Cedraz Morais Zannety Conceição Silva do Nascimento Souza; Pricila Oliveira de Araújo. | ||

| 14. An ethnography on perceptions of pain in Dutch “Natural” childbirth 35 | Katie Logsdon; Carolyn Smith- Morris. | ScienceDirect | My birth, my choice |

| 15. Meanings of the childbirth plan for women that participated in the Meanings of Childbirth Exhibit 36 | Fernanda Soares de Resende Santos; Paloma Andrioni de Souza, Sônia Lansky; Bernardo Jefferson de Oliveira; Fernanda Penido Matozinhos; Ana Luiza Nunes Abreu; Kleyde Ventura de Souza; Érica Dumont Pena. | Scopus | |

| 16. Assistance to women for the humanization of labor and birth (37) | Thais Cordeiro Xavier de Barros; Thayane Marrón de Castro; Diego Pereira Rodrigues; Phanya Gueitcheny Santos Moreira; Emanuele da Silva Soares; Alana Priscila da Silva Viana. | Cinahl | |

| 17. Choosing the home planned childbirth: a natural and drug- free option 38 | Heloisa Ferreira Lessa; María Antonieta Rubio Tyrrell; Valdecyr Herdy Alves; Diego Pereira Rodrigues. | ||

| 18. Between rites and contexts: Decisions and meanings attached to natural childbirth humanized 39 | Bárbara Regia Oliveira de Araújo; María Cristina Soares Figueiredo Trezza; Regina María dos Santos; Larisa Lages Ferrerde Oliveira; Laura María Tenório Ribeiro Pinto. | ||

| 19. Nurses’ practices to promote dignity, participation and empowerment of women in natural childbirth 40 | Andrea Lorena Santos Silva; Enilda Rosendo do Nascimento; Edméia de Almeida Cardoso Coelho. | ||

| 20. At pains to consent: A narrative inquiry into women’s attempts at natural childbirth 41 | Alison Happel-Parkins; Katharina A. Azim | ScienceDirect | Making visible the invisible: Normalizing violence in childbirth |

| 21. A qualitative exploration of women’s and their partners’ experiences of birth trauma in Australia, utilizing critical feminist theory 42 | Paige L. Tsakmakis; Shahinoor Akter; Meghan A. Bohren. | ||

| 22. Dehumanization during delivery: Meanings and experiences of women cared for in the Medellín Public Network 43 | Cristina María Mejía Merino; Lida Faneyra Zapata; Diana Patricia Molina Berrío; Juan David Arango Urrea. | PubMed | |

| 23. Obstetric violence a qualitative interview study 44 | Ana Anborn; Hafrún Rafnar Finnbogadóttir. | ||

| 24. Discussing obstetric violence through the voices of women and health professionals 45 | Virgínia Junqueira Oliveira; Cláudia Maria de Mattos Penna. | Scopus | |

| 25. Adolescent childbirth: Qualitative elements of care 46 | cleci de Fátima Enderle; nalú Pereira da costa Kerber; Lulie Rosane odeh Susin; bruna Goulart Gonçalves. | ||

| 26. Representations of puerperal women regarding their delivery assistance: a descriptive study 47 | Keli Regiane Tomeleri da Fonseca Pinto; Adriana ValongoZani; Catia Campaner Ferrari Bernardy; Cristina María García de Lima Parada. | ||

| 27. Experience of women in the transfer from planned home birth to hospital 48 | Marina Fabricio Ribeiro Pereira; Suellen de Sousa Rodrigues; Mariana de sousa Dantas Rodrigues; Wilma Ferreira Guedes Rodrigues; Morganna Guedes Batista; luanna silva braga; Smalyanna Sgren da Costa Andrade. | Cinahl | |

| 28. The knowledge of puerperal women on obstetric violence 49 | Fabiana da Conceição Silva; Magda Rogeria Pereira Viana; Fernanda Claudia Miranda de Amorim; Juscélia María de Moura Feitosa Veras; Rafael de castro santos; Leonardo López de Sousa. | ||

| 29. The extent of the implementation of reproductive health strategies in Catalonia (Spain) (2008-2017) 50 | Marta Benet, Ramon Escuriet, Manuela Alcaraz-Quevedo, Sandra Ezquerra y Margarida Pla | ScienceDirect | The ritual of childbirth: Women’s dignity |

| 30. Women and waterbirth: A systematic meta-synthesis of qualitative studies 51 | Claire Clews, Sarah Church, Merryn Ekberg | Cinahl | |

| 31. “It was worth it when I saw his face”: experiences of primiparous women during natural childbirth 52 | Juliane Scarton; Lisie Alende Prates; Laís Antunes Wilhelm; Silvana Cruz da Silva; Andressa Batista Possati; Caroline Bolzán Ilha; Lúcia Beatriz Ressel. | ||

| 32. Model maternity with exclusive nursing care: social representations 53 | Danelia Gómez Torres; Dolores Martínez Garduño; Gabriela Téllez Rojas; Elizabeth Bernardino. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Microaggressions and Macro-impacts: Childbirth: Between Pain and Fear

Forms of aggression manifest themselves in all areas and govern the daily behavior of human beings; aggressive behavior often becomes socially acceptable in forms such as microaggressions or subtle, routine expressions that may not overtly suggest violence but that nonetheless convey offensive messages, evoke feelings of inferiority, and assign culturally devaluing roles to individuals 54; findings in the literature reveal that women in labor experience microaggressions, primarily due to the treatment they receive from healthcare personnel since they depersonalize the woman, isolate her in the process because they shift their focus solely to the medical problem or procedure, they do not talk to her, do not let her be autonomous and let her endure a significant amount of pain 22,23,25.

Socioeconomic, ethnic, and cultural differences influence the care provided by health institutions; healthcare personnel fail to understand the unique challenges and barriers of women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, resulting in them providing differentiated and disrespectful treatment, acting with disrespect towards this socially vulnerable population, making derogatory comments, particularly towards those who are single mothers, adolescent mothers, poor or uneducated 22,25,31,50.

On the other hand, negative experiences of childbirth are socially shared, in terms of pain, and associated with fear and suffering since women expect mistreatment before entering the delivery room because they are unprepared or have insufficient knowledge, fear hospitals and distrust the staff 22,43,52. The experiences that produce discomfort, insecurity and psychological damage generate macro-impacts that lead to the perception that health institutions are hostile and unsuitable environments for a natural and humanized childbirth 23,24,26.

Acting with Respect: Childbirth as a Natural Process

Childbirth is a natural process, and healthcare personnel and the community need to embrace their responsibility toward women, fostering empathetic communication, and support for those who have chosen to continue with their pregnancy and plan their childbirth, according to their unique characteristics, expectations and desires, ensuring they feel safe, comfortable and respected 27-29, Women should have the freedom to navigate between different models of care, that is, the traditional model, rooted in cultural experience; and the biomedical or welfarist model, guided by the delivery care protocols managed by health institutions 27,29,30.

Healthcare personnel are important in this experience, as they need to ensure that women feel safe within the facilities and trust them during the childbirth process; for this, they must be up to the task, without dehumanizing the procedure and cultivating empathy. To achieve this, appropriate facilities should be created for natural childbirth that provide a secure environment 52, in which knowledge, skills, values, moral and ethical principles for the care of women during pregnancy, childbirth the postpartum period are integrated, in addition to attending to their needs, respecting their body and their process, for an excellent experience during childbirth 27,37.

Healthcare personnel have a crucial role in adhering to practices such as informed consent, reinforcing women's autonomy, and respecting their ability to freely choose interventions, whether from the biomedical or traditional model 27,29,30. They should also offer women the option to select their birth companion and ensure they feel comfortable, preserving their autonomy throughout the vaginal birth process 28,30.

Childbirth holds significant symbolic and cultural meaning, reflecting diverse social, cultural, and ethnic values 33. Recognizing the profound value women attribute to childbirth, it is imperative to take proactive measures to prevent violence and ensure their respectful treatment, particularly during this pivotal process.

Silencing, Enduring, and Bearing

Globally, there is a widespread lack of awareness regarding human rights; women during pregnancy and childbirth are no exception. Lack of knowledge often results in a loss of control over their bodies, leaving them vulnerable to professionals who perpetrate violence against them, while they assume a passive role 32,49, and the mechanisms for such mistreatments are unknown, leading women to prefer to remain silent 31.

Women who rely on the health system assume that the actions taken during their care are correct, preferring to remain silent rather than challenge those who violated their rights, they renounce their bodies so that healthcare professionals take care of everything for the sake of their baby, and once they hold their baby in their arms, they justify the practices they endured 31,33,34 which, on occasions, can be so shameful that they prefer to keep quiet about them, which is why they hide them deep within themselves 25,33.

Women in vulnerable conditions who are admitted to a health institution are repressed and must endure and remain silent during childbirth 46; As a consequence of this, given their past experiences and what they have heard from others, they hide their plans and expectations for childbirth from society, because they believe the family may influence their decisions and that the hospital environment will not be friendly, nor will it share their decisions, so they believe that by remaining silent the delivery will be easier and faster, creating a favorable environment for obstetric violence and a bad experience 31-34.

The sociocultural context often frames childbirth as a painful ordeal, dominated by norms dictated by healthcare personnel who know everything and decide everything, thereby limiting women's autonomy over their bodies. Painful childbirth is linked with previous negative experiences, which foster biases about vaginal childbirth in medical institutions 26. Consequently, vaginal childbirth becomes a process where orders must be followed to facilitate the healthcare team's work 32.

My Birth, My Choice

Childbirth is a unique, special and unforgettable moment, that requires a profound physical and mental connection between the mother and her surroundings, but it does not necessarily need to occur in a hospital setting 35; for some women, childbirth is a process influenced by their ancestors and origins, grandmothers and mothers; for this reason, they decide not to go to medical institutions 35. Humanizing childbirth involves recognizing the woman as the central figure and interacting with her during the decision-making process regarding her care 36,37,39.

Ideally, women should listen to their bodies and be able to make decisions based on the education they receive from the professional who helps them to clear up doubts and clarify concepts about childbirth 35. Fostering empowerment and promoting self-education is essential for decision-making and management of childbirth from planning to completion. Providing complete information and adequate medical support to all women facilitates women's control of their childbirth 35,40.

The education provided by health professionals should make women aware of their sexual and reproductive rights and include information so that they understand the meaning of obstetric violence, which will allow them to detect, stop and report it in time, to guarantee their integrity and dignity during labor. In addition, women should be able to choose the birth plan they want to have: traditional, home or water birth, which will strengthen their autonomy when making decisions 38.

Some procedures are performed out of necessity to maintain or restore the patient's health; however, women should know which interventions are going to be performed 41; for this reason, respectful communication is fundamental, signing the consent form in which the professional informs when, why and how the delivery will be performed so that women know their state of health and share it with their companion; they should know the woman's evolution to provide support according to the particularity of the situation 36.

Making the Invisible, Visible: Normalizing Violence During Childbirth

Little is said about women's experiences during childbirth in health centers because the care is generally unsatisfactory; only when the mothers and their babies are at home do they share their negative experiences with family members 31,48. In hospitals, medical interventions are frequently performed to expedite the delivery process, often without respecting the patients' wishes or considering cultural factors 41,46; the staff acts in an insensitive manner, prioritizing interventions such as the Kristeller maneuver, routine episiotomies or forceps, most of which are unknown to them 42,43,49.

Women tend to normalize these situations, adopting the role of the compliant patient, they do not bother and refrain from asking questions, fearing that opposing the decisions of healthcare personnel could lead to negative repercussions 43,44; the healthcare personnel work without saying anything, through scolding or even physical force, they coerce women into adopting the correct position for delivery 41,44,45,47,48, they speak without giving importance to the mother's process, their interest is solely focused on ensuring the fetus is born alive 41,42,44.

Healthcare institutions and personnel often act disrespectfully, undermining women's empowerment 48, they are insulted and ignored 41,43,44; they use fear to coerce them into consenting to medical interventions under pressure; most of them sign consent forms for them to perform the procedure and expedite the delivery 41,43. While some are grateful that they did not suffer more 41, this has repercussions and emotional imbalances that prevent them from developing a normal life after childbirth or alter their sexual and reproductive plans 48,49. Professionals have normalized violence; this situation continues, and the subject is not discussed because very few women dare to report it since they have normalized this type of treatment 32,42.

The Ritual of Birthing: Women's Dignity

Childbirth is a rite of life in which assistance is provided without interventions or procedures and for which the Healthcare personnel become emotional and scientific support 51, since they provide privacy and good treatment during care 52,53. Some women make a birth plan 35,50 with which they take control and request privacy, limit the number of professionals present 50 and obtain silence, make decisions and express themselves freely 50,52.

Satisfying the woman's desires during labor makes this experience an enriching moment; water birth is a stabilizing, temporary and protective space that facilitates the transition of the baby from the uterus to the water 51, it can be performed in health institutions or with trained personnel who at the same time become educators and support for the women 50,53. The best place for delivery is where the mother feels safe, as long as the home, the water or the health institution favors the mother-child bond 51,52.

An essential factor in ensuring the satisfaction and dignity of women during childbirth is their companion, a guardian or protector who can prevent obstetric violence 50,52,53. A partner who is involved throughout the gestation process and prepares alongside the mother for childbirth expresses the fulfillment of sharing and participating in this meaningful experience 50,53.

The analyzed articles highlight positive childbirth processes. They show the patience, privacy and respect that the healthcare professional 50,52,53 exhibits with the patient, going from being mere assistants to an accomplice and co-authors of the event, as long as there is a relationship based on communication 41,53, with extensive discussions before starting the delivery, clarify doubts and provide a safe, healthy and satisfactory delivery for the couple 41,52; This produces a positive impact at the individual and social levels, a positive experience that encourages them come again to give birth 47 in those spaces where they feel safe and protected.

Discussion

The integrative review made it possible to show the aspects of childbirth care that need to be avoided and the practices that should be encouraged; despite advancements in technology have been made for patient care in medical institutions, there remains a significant need to humanize the care given to women during childbirth 23,27,29,30,33,41,42,46-48. Likewise, prejudice, decision-making above the patient's wishes, and mistreatment should be avoided, especially towards women of lower socioeconomic status 31,32,40,45, healthcare personnel exhibit patience and refrain from behaviors that contribute to obstetric violence 22,24,34,36,37,39,49.

Obstetric violence occurs due to degrading working conditions, particularly when healthcare personnel feel overwhelmed by their workload, this leads to a loss of patience, mistreatment of mothers during childbirth, showing disrespect, violence and harassment 55. The studies highlight the perspectives of professionals attending labor and delivery, in relation to the power dynamics between doctors and nurses, a situation that adds to inadequate conditions that contribute to obstetric violence; for this reason, it is necessary to propose interventions on the service provided by these professionals to their patients 56,57.

Additional research explores the experiences of the birth attendants, especially fathers, who, with adequate information, a supportive environment, a positive attitude and willingness from midwives, are more likely to actively participate in the childbirth process. In addition, midwives have a crucial role in ensuring that men are well-prepared so that this experience is positive and strengthens family unity 58,59.

While there is extensive literature on humanized childbirth, global reports continue to highlight instances of violence against women during childbirth, therefore, to achieve a positive impact on care during this event, it is essential to prioritize meeting women's expectations and birth plans, enhancing their autonomy, providing support, respecting their privacy and their sexual and reproductive rights 25,28,38,44,47,50,51,53. The best healthcare team is the one that provides security, does not impose, advises and actively participates in the process, allows for a natural process, and makes the woman feel that she has a trained healthcare team, according to the plan 26,29,30,35,39,43,46,52.

Among the limitations of the research, the results did not consider the perspectives of the companions and healthcare personnel attending deliveries. The study solely focused on what the woman considered about natural childbirth care; thereby omitting the experience of women regarding cesarean section.

Conclusion

Women's childbirth experiences worldwide are both positive and negative, influenced by socio-cultural contexts shaping both biomedical and traditional models. These experiences leave lasting impacts on women's lives, highlighting a pressing need for societal education to combat historical violations during childbirth. It is the moment to uphold their reproductive and sexual rights, recognizing women as deserving of dignity and respect.

Thus, this project serves as a pivotal step toward understanding global healthcare realities, especially concerning women's childbirth experiences. Its goal is to ensure women have positive, empowering experiences, feel safe, and actively engage in health services as vital participants in the team-partner-family triad, fostering successful processes of natural and humanized childbirth. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.