Introduction

The discussion on palliative care (PC) has progressed as a result of demographic changes, disease patterns, and the number of people living with chronic conditions with no prospect of recovery 1,2. The need for comprehensive care that supports strategies for addressing life-threatening illnesses renders this approach extremely necessary, especially in terms of hospitalization in high-tech and interventional environments, such as the perioperative setting to redefine praxis in a reality with a reserved prognosis 3.

In the surgical setting, which is highly complex and requires hard technologies, palliation should be understood as an innovative, humanized approach focused on the concepts of comfort and suffering relief; it should never be understood as diverging from or opposing conventional perioperative practice 4-6. On the contrary, this strategy should be complementary to surgery, and, in turn, surgery should support palliation to provide comfort and optimize the patient's well-being. 7,8.

In this sense, it should be noted that surgical culture and PC are not mutually exclusive, nor are they sequential 5. Even if all the anxiety and hope of patients who undergo surgery regarding their recovery is factored in, the dissolution of platitudes concerning the exclusivity of one practice or another is imperative in an attempt to establish full, quality care, especially for the elderly, who are the most demanding population in terms of PC, due to their susceptibility and the coexistence of morbidities. 9,10.

Individuals over the age of 60 who have two or more associated co-morbidities comprise the percentage of the population that needs hospitalization the most in the last year of life, with a high probability of undergoing surgical procedures 11,12. In a broad overview, data from MediCare, the US health insurance system, estimates that 500,000 elderly people in the United States alone undergo high-risk surgery, with a mortality rate of approximately 20 %. 13.

It was estimated that of the 5,411,087 surgeries performed by the Unified Health System in Brazil in 2022, approximately 40 % were performed on elderly patients 14,15. Regarding elective surgeries, multimorbidities are the main underlying causes for these procedures, with special emphasis on neoplasms and malignant tumors, which are the second leading cause of mortality among the elderly in Latin America, the European Union, and the USA, only behind cardiocirculatory diseases 2,12,16.

Procedures such as tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy are routine treatments that relieve the symptoms of esophageal cancer, head and neck cancer, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 5,11. Intestinal detour surgeries and colostomies are performed to relieve malignant intestinal obstruction and palliative amputations are common in vascular surgery 5,11,12.

Despite the unquestionable organic stress imposed on individuals over the age of 60 as a result of such a procedure, surgeries, when well prescribed, provide unparalleled comfort and relief 6,17. Therefore, the challenge lies in the complexity of implementing and integrating PC into the perioperative process, enabling them to juxtapose these approaches early on, with special emphasis on nursing, in its role as a protagonist, whether in providing care that aims to identify patients in need of palliation, or in developing care that provides dignity, based on strategies and, above all, being empathetic and humane 3,18.

For nurses, PC includes aggressive management of pain and symptoms, psychological, social, and spiritual support, as well as discussions concerning advanced care planning, which can include decision-making about treatment and coordination of complex care 19. Specialized PC for surgical elderly patients, provided by a trained nursing team, can help manage complex symptoms, provide additional support to families, solve conflicts in treatment objectives and approaches, and assist in care transition 18.

To this end, it is necessary to understand and know the nursing actions and care -pre-, trans-, or post-operative- provided to these patients in wards or intensive care units (ICUs), and, therefore, understand the challenges involved in the implementation of this process, as well as whether the provision of care occurs empirically or systematically, whether it is frequent or infrequent, and what dimensions are involved in this process.

It is essential, thus, that in a perioperative hospitalization setting, such as the one discussed here, the professional nurse should not only be the one who structures patient care, but also the one who is responsible for welcoming, addressing, and alleviating biophysical and psychological suffering 20,21.

Hence, this scoping review aimed to map and identify the existing works in the literature on nursing actions focused on palliative care for the elderly in a surgical hospitalization setting, considering the intrinsic relationship between the aging phenomenon, illness processes, the need for surgical procedures, and the establishment of palliative care by the nursing team. This study not only helps to elucidate the role of the profession but is also justified by the inherence and pertinence of a widespread, common, but scarcely addressed theme, in an attempt to improve efforts to provide comfort and quality of care.

Materials and Methods

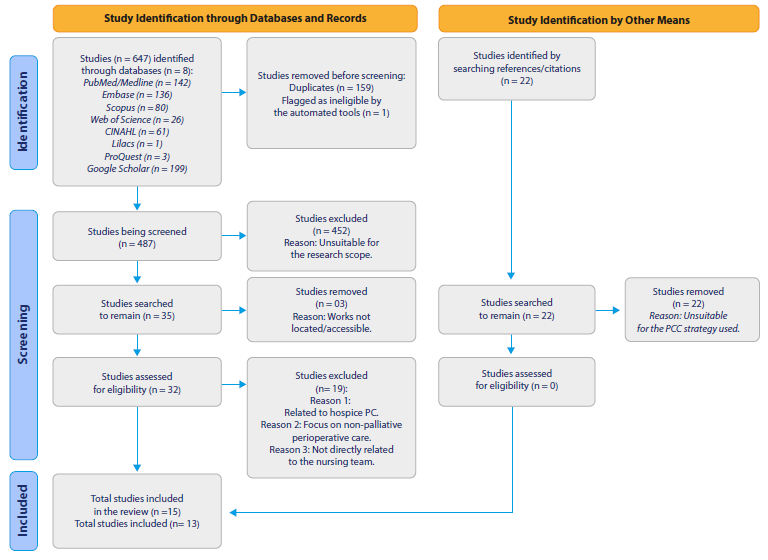

This is a descriptive, exploratory, scoping review, based on a specific manual proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute 22, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review tool, with its extension for scoping reviews (Prisma-ScR). This method allows the main concepts to be mapped, research areas to be clarified, and knowledge gaps to be identified (Figure 1).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1 PRISMA-ScR Flowchart for the Study Search and Selection Process

The research stages were the following: i) development of the research question; ii) inclusion and exclusion criteria selection; iii) identification of key terms; iv) identification of databases; v) study selection, and vi) mapping the articles and reporting the results.

The "population, concept, context" (PCC) strategy was used to develop this study, which includes the following eligibility criteria: for the population - elderly people who meet the WHO definition of elderly (65 years) or the Elderly Statute (60 years, in the Brazilian context [23,24]); concept - PC is defined as care provided by a multidisciplinary team, which aims to improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing a life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering, early identification, impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other physical, social, psychological, and spiritual symptoms (WHO [25]). Regarding the context - studies referring to elderly people in perioperative circumstances were included. Thus, only productions that specifically included PC nursing interventions for elderly patients in perioperative settings were included.

To guide the collection of scientific evidence, the following question was asked: What are the nursing actions/care provided to elderly people receiving PC in a surgical hospitalization setting?

The search was conducted independently by two researchers and a reviewer in June 2023, and the results were then compared and merged into a single database provided by the Rayyan® software. However, data was first collected from the Medline/PubMed database by testing MeSH terms and index terms (Table 1). Following this step, the search strategy was completed and implemented in the other databases used in the review, according to the particularities of each one, which was coordinated by a professional librarian.

Table 1 Databases and Search Strategies

| Database | Search strategy | Results June 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Medline/ PubMed | (“Nursing Care”[MeSH Terms] OR “Nursing Care”[All Fields] OR “nursing interventions”[All Fields] OR “nursing intervention”[All Fields] OR “Nursing”[MeSH Terms] OR “Nursing”[All Fields]) AND (“Aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “Aged”[All Fields] OR “Elderly”[All Fields] OR “aged, 80 and over”[MeSH Terms] OR “80 and over”[All Fields] OR “Oldest Old”[All Fields] OR “Nonagenarian”[All Fields] OR “Nonagenarians”[All Fields] OR “Octogenarians”[All Fields] OR “Octogenarian”[All Fields] OR “Centenarians”[All Fields] OR “Centenarian”[All Fields] OR “geriatric”[All Fields] OR “Middle Aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “Middle Aged”[All Fields] OR “Middle Age”[All Fields]) AND (“Palliative Care”[MeSH Terms] OR “Palliative Care”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Treatment”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Treatments”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Therapy”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Supportive Care”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Surgery”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Medicine”[MeSH Terms] OR “Palliative Medicine”[All Fields] OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”[MeSH Terms] OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Nursing”[All Fields] OR “Palliative Care Nursing”[All Fields] OR “Hospice Nursing”[All Fields] OR “Hospice Care”[MeSH Terms] OR “Hospice Care”[All Fields] OR “Hospice Programs”[All Fields] OR “Hospice Program”[All Fields] OR “Bereavement Care”[All Fields] OR “Terminal Care”[MeSH Terms] OR “Terminal Care”[All Fields] OR “End of Life Care”[All Fields] OR “End of Life Cares”[All Fields] OR “Hospices”[MeSH Terms] OR “Hospices”[All Fields] OR “Hospice”[All Fields] OR “Critical Illness”[MeSH Terms] OR “Critical Illness”[All Fields] OR “Critical Illnesses”[All Fields] OR “Critically Ill”[All Fields]) AND (“Perioperative Period”[MeSH Terms] OR “Perioperative Period”[All Fields] OR “Perioperative Periods”[All Fields] OR “Perioperative Care”[MeSH Terms] OR “Perioperative Care”[All Fields] OR “Surgical patients”[All Fields] OR “Surgical patient”[All Fields]) | 142 |

| Embase | (‘nursing care’/de OR ‘nursing care’ OR ‘nursing interventions’ OR ‘nursing intervention’/de OR ‘nursing intervention’ OR ‘nursing’/de OR nursing) AND (‘aged’/de OR aged OR ‘elderly’/ de OR elderly OR ‘80 and over’ OR ‘oldest old’ OR ‘nonagenarian’/de OR nonagenarian OR ‘nonagenarians’/de OR nonagenarians OR ‘octogenarians’/de OR octogenarians OR ‘octogenarian’/ de OR octogenarian OR ‘centenarians’/de OR centenarians OR ‘centenarian’/de OR centenarian OR ‘geriatric’/de OR geriatric OR ‘middle aged’/de OR ‘middle aged’ OR ‘middle age’/de OR ‘middle age’) AND (‘palliative care’/de OR ‘palliative care’ OR ‘palliative treatment’/de OR ‘palliative treatment’ OR ‘palliative treatments’ OR ‘palliative therapy’/de OR ‘palliative therapy’ OR ‘palliative supportive care’ OR ‘palliative surgery’/de OR ‘palliative surgery’ OR ‘palliative medicine’/de OR ‘palliative medicine’ OR ‘hospice and palliative care nursing’/de OR ‘hospice and palliative care nursing’ OR ‘palliative nursing’/de OR ‘palliative nursing’ OR ‘palliative care nursing’/de OR ‘palliative care nursing’ OR ‘hospice nursing’/de OR ‘hospice nursing’ OR ‘hospice care’/de OR ‘hospice care’ OR ‘hospice programs’ OR ‘hospice program’ OR ‘bereavement care’/de OR ‘bereavement care’ OR ‘terminal care’/de OR ‘terminal care’ OR ‘end of life care’/de OR ‘end of life care’ OR ‘end of life cares’ OR ‘hospices’/de OR hospices OR ‘hospice’/de OR hospice OR ‘critical illness’/de OR ‘critical illness’ OR ‘critical illnesses’ OR ‘critically ill’/de OR ‘critically ill’) AND (‘perioperative period’/de OR ‘perioperative period’ OR ‘perioperative periods’ OR ‘perioperative care’/de OR ‘perioperative care’ OR ‘surgical patients’ OR ‘surgical patient’/de OR ‘surgical patient’) | 136 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Nursing Care” OR “nursing interventions” OR “nursing intervention” OR nursing) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Aged OR Elderly OR “80 and over” OR “Oldest Old” OR Nonagenarian OR Nonagenarians OR Octogenarians OR Octogenarian OR Centenarians OR Centenarian OR geriatric OR “Middle Aged” OR “Middle Age”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Palliative Care” OR “Palliative Treatment” OR “Palliative Treatments” OR “Palliative Therapy” OR “Palliative Supportive Care” OR “Palliative Surgery” OR “Palliative Medicine” OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Palliative Nursing” OR “Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Hospice Nursing” OR “Hospice Care” OR “Hospice Programs” OR “Hospice Program” OR “Bereavement Care” OR “Terminal Care” OR “End of Life Care” OR “End of Life Cares” OR Hospices OR Hospice OR “Critical Illness” OR “Critical Illnesses” OR “Critically Ill”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Perioperative Period” OR “Perioperative Periods” OR “Perioperative Care” OR “Surgical patients” OR “Surgical patient”) | 80 |

| Web of Science | TS=(“Nursing Care” OR “nursing interventions” OR “nursing intervention” OR nursing ) AND TS=(Aged OR Elderly OR “80 and over” OR “Oldest Old” OR Nonagenarian OR Nonagenarians OR Octogenarians OR Octogenarian OR Centenarians OR Centenarian OR geriatric OR “Middle Aged” OR “Middle Age”) AND TS=(“Palliative Care” OR “Palliative Treatment” OR “Palliative Treatments” OR “Palliative Therapy” OR “Palliative Supportive Care” OR “Palliative Surgery” OR “Palliative Medicine” OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Palliative Nursing” OR “Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Hospice Nursing” OR “Hospice Care” OR “Hospice Programs” OR “Hospice Program” OR “Bereavement Care” OR “Terminal Care” OR “End of Life Care” OR “End of Life Cares” OR Hospices OR Hospice OR “Critical Illness” OR “Critical Illnesses” OR “Critically Ill”) AND TS=(“Perioperative Period” OR “Perioperative Periods” OR “Perioperative Care” OR “Surgical patients” OR “Surgical patient”) | 26 |

| CINAHL | (“Nursing Care” OR “nursing interventions” OR “nursing intervention” OR nursing) AND (Aged OR Elderly OR “80 and over” OR “Oldest Old” OR Nonagenarian OR Nonagenarians OR Octogenarians OR Octogenarian OR Centenarians OR Centenarian OR geriatric OR “Middle Aged” OR “Middle Age”) AND (“Palliative Care” OR “Palliative Treatment” OR “Palliative Treatments” OR “Palliative Therapy” OR “Palliative Supportive Care” OR “Palliative Surgery” OR “Palliative Medicine” OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Palliative Nursing” OR “Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Hospice Nursing” OR “Hospice Care” OR “Hospice Programs” OR “Hospice Program” OR “Bereavement Care” OR “Terminal Care” OR “End of Life Care” OR “End of Life Cares” OR Hospices OR Hospice OR “Critical Illness” OR “Critical Illnesses” OR “Critically Ill”) AND (“Perioperative Period” OR “Perioperative Periods” OR “Perioperative Care” OR “Surgical patients” OR “Surgical patient”) | 61 |

| Lilacs | (“Nursing Care” OR “nursing interventions” OR “nursing intervention” OR nursing OR “Cuidados de Enfermagem” OR “Cuidado de Enfermagem” OR “Assistência de Enfermagem” OR “Atendimento de Enfermagem” OR “Atención de Enfermería” OR “Cuidado de Enfermería” OR “Cuidados de Enfermería” OR enfermeiros OR enfermeiras OR enfermeras OR enfermeros OR enfermagem OR enfermería) AND (aged OR elderly OR “80 and over” OR “Oldest Old” OR nonagenarian OR nonagenarians OR octogenarians OR octogenarian OR centenarians OR centenarian OR geriatric OR “Middle Aged” OR “Middle Age” OR idoso OR idosos OR idosa OR idosas OR “Pessoa de Idade” OR “Pessoas de Idade” OR anciano OR ancianos OR “Adulto Mayor” OR “Persona Mayor” OR “Persona de Edad” OR “Personas Mayores” OR “Personas de Edad” OR “Idoso de 80 Anos ou mais” OR centenarios OR nonagenarios OR octogenarios OR velhíssimos OR “Anciano de 80 o más Años” OR viejísimos OR geriátrico OR geriátricos OR geriátrica OR geriátricas OR “Meia Idade” OR “Mediana Edad”) AND (“Palliative Care” OR “Palliative Treatment” OR “Palliative Treatments” OR “Palliative Therapy” OR “Palliative Supportive Care” OR “Palliative Surgery” OR “Palliative Medicine” OR “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Palliative Nursing” OR “Palliative Care Nursing” OR “Hospice Nursing” OR “Hospice Care” OR “Hospice Programs” OR “Hospice Program” OR “Bereavement Care” OR “Terminal Care” OR “End of Life Care” OR “End of Life Cares” OR hospices OR hospice OR “Critical Illness” OR “Critical Illnesses” OR “Critically Ill” OR “Cuidados Paliativos” OR “Assistência Paliativa” OR “Cuidado Paliativo” OR “Tratamento Paliativo” OR “Apoyo en Cuidados Paliativos” OR “Asistencia Paliativa de Apoyo” OR “Atención Paliativa” OR “Tratamiento Paliativo” OR “Medicina Paliativa” OR “Enfermagem de Cuidados Paliativos na | 1 |

Note: The search strategies were performed for each database using specific word combinations and strings with the support of a librarian.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The search was conducted in the following databases: Medline/ PubMed (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online); BVS/Lilacs (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature); Embase (Excerpta Medica dataBASE); Scopus; Cinahl (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature); and Web of Science, searching for scientific works that had covered the themes in the aforementioned PCC strategy. The search for gray literature included a focused search in the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (ProQuest) and Google Scholar databases. From the latter, the first 199 results were included.

After exploration, the results were then selected and refined, based on the instrument previously validated in Ursi's studies 26, which covers the following items: identification of the original article, the study's methodological characteristics, assessment of methodological rigor, interventions measured, and results found.

The inclusion criteria were studies that covered at least three of the four thematic categories (nursing care + PC + the elderly + surgery), that were primary research, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical trials, without time limits or language limitations to provide a more comprehensive overview of the theme.

Books, documents, informative texts, editorial articles, and clinical manuals were excluded, as well as works with restricted access or which failed to reference PC and the perioperative environment (clinic/surgical ICU). To read the content, paid access to the Sistema de Comunidade Acadêmica Federada da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nível Superior (Federated Academic Community System of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) at the Universidade Federal da Paraíba was required.

The selection was based on three steps, namely: 1st step: listing the databases and applying a pilot test to the form in the Medline database with the application of the inclusion criteria used. 2nd step: a broad search, the exclusion of duplicate results, title, and abstract reading to fit the PCC strategy by two independent reviewers and a decision-maker reviewer, thus selecting the eligible materials. 3rd step: complete reading of the eligible materials and their references.

Finally, there is no conflict of interest in this research. The study protocol is registered on the Open Science Framework platform under DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/HSC75. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Center of the Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil, under ethics review certificate 67165623.0.0000.5188. The ethical requirements complied with the norms governed by Resolutions 466/2012 and 510/2016 of the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Results

In the present review, 509 studies were found, distributed as follows: 142 (27.89 %) found in PubMed/Medline; 136 (26.71 %,) in Embase; 80 studies (15,71 %) in Scopus; CINAHL with 61 (11.9 %); Web of Science with 26 (5.10 %), and Lilacs with one study (0,19 %). The gray literature repositories represented 202 productions (39.68 %) in the sample, of which three were from ProQuest Dissertations (0.58 %) and 199 from Google Scholar (39.09 %). In addition, 22 (4.32 %) publications were included when reading references and citations found on the websites and repositories of autonomous organizations.

After applying the PCC strategy and refining it, the final sample consisted of 13 articles (2.55 % of the total), which were published between 2001 and 2023 (22 years). All these works were scientific articles published in journals. Table 2 presents the reference data, objectives, method, population, findings, and considerations of the studies regarding the technologies and strategies used for the palliative treatment of elderly surgical patients.

Table 2 Characteristics of the Studies of the Scoping Review Sample

| Article title/authors | Country/ year | Journal | Study design | Participants | Objective | Important results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Geriatrics Surgery Verification Program and the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative: Coupling Two Programs to Improve Advanced Care Planning for Older Veterans Undergoing Surgery/ Unruh MJ, Jones TS, Horney C, Davidson S | USA/2023 | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management | Retrospective cohort, data collection from electronic medical records | N = 1264 veterans aged 65 and over | To evaluate the effectiveness of combining war veterans’ programs to improve advanced care planning for the elderly undergoing surgery. |

The percentage of veterans who completed an advanced directive increased from 38 % to 78 %. The study also found that the percentage of veterans who discussed their end-of-life care preferences with their providers increased from 53 % to 88 %. There is a need to ensure that elderly people undergoing surgery have the opportunity to discuss their preferences with their providers and make informed decisions about their care. |

| 2 | Palliative Care Interventions for Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review/ Lilley EJ, Khan KT, Johnston FM, Berlin A, Bader AM, Mosenthal AC, Cooper Z | USA/2021 | JAMA Surgery | Systematic review | N = 8575 single patients in the 25 articles analyzed | To evaluate the effect of PC interventions on surgical patients. |

The study focused on establishing preoperative interventions for decision- making, improving the quality of communication, symptom management, and reducing the use of healthcare resources to lower costs. PC interventions can be an important part of surgical patient care. |

| 3 | The Quality of Palliative Care from the Perspectives of the Elderly with Cancer at Firoozgar Hospital in 2019: A Cross-sectional Study/ Farzadnia F, Bastani F, Haghani H | Iran/2021 | Iran Journal of Nursing | Quantitative descriptive study | N = 200 elderly cancer patients | To evaluate the quality of PC from the perspective of elderly cancer patients admitted to surgical/ clinical wards. |

Pain management and psychological support, according to the study, were insufhcient, reducing the quality of dying in Iran. The findings of this study can be used to improve the quality of PC for elderly cancer patients. The researchers recommend developing a specific structure for nurses to provide PC to cancer patients. |

| 4 | The Role of the Advanced Practice Nurse in Geriatric Oncology Care/ Morgan B, Tarbi E | USA/2019 | Seminars in oncology nursing | Literature review | Number of participants not stated | To evaluate the role of advanced practice nurses in geriatric oncology care. |

Nurses should formulate a care plan, provide psychosocial support to the family, and promote dehospitalization in PC. Addressing geriatric syndromes such as incontinence, delirium, pressure damage, falls, and functional decline. |

| 5 | Palliative Nursing Care as Applied to Geriatric: An Integrative Literature Review/ Guerrero JG | USA/2019 | Nursing Palliative Care | Literature review | Number of participants not stated | To evaluate the role of nurses in providing PC for the elderly. |

The actions found in the study were evaluation of physical symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and nausea, providing emotional and psychological support, coordinating care and education, and participating in ethical discussions. The nursing team is essential in ensuring that the elderly receive the care they need to enjoy quality of life at the end of life. |

| 6 | Perioperative Palliative Care Considerations for Surgical Oncology Nurses/Sipples R, Taylor R, Kirk-Walker D, Bagcivan G, Dionne- Odom JN, Bakitas M | USA/2016 | Seminars in Oncology Nursing | Literature review | Number of participants not stated | To explore the opportunities for incorporating PC into the management of perioperative oncology patients. |

Symptom management, facilitating communication and decision making, psychosocial support, and working on transitions and continuity of care are the actions listed by the study concerning nursing professionals. The article highlights the need for formal education in PC and the resources available to surgical oncology nurses. |

| 7 | Comfort in Palliative Care: The Know-How of Nurses in General Hospital/Durante ALTC, Tonini T, Armini LR | Brazil/2014 | Journal of Nursing UFPE/ Revista de Enfermagem UFPE | Qualitative descriptive study | N = 30 nurses working in medical- surgical clinics | To identify nursing care related to the comfort of patients undergoing PC. |

The nurses in the study prioritize interventions to promote comfort, including pain management, symptom management, dyspnea, hygiene, and oxygen therapy. They also request support from the multi- professional team and, finally, provide emotional and spiritual support. There is a recommendation for these professionals to prioritize the development of a care plan, improve communication, and for hospitals to develop and implement policies and procedures that support the provision of comfort care. |

| 8 | When the end is near: An ICU patient who died at home/de Vries AJ, van Wijlick EHJ, Blom JM, Meijer I, Zijlstra JG | Netherlands /2011 | Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde | Experience report | A 64-year-old elderly person N = 1 participant | To describe the process of transferring a 64-year-old surgical patient from an ICU to their home. |

The transfer of care, the role of the nursing team, the following administrative steps, the natural cause of death as a requirement factor in PC, and dehospitalization. Nursing actions included pain and dyspnea management, oxygen therapy, continuous monitoring, psychological and emotional support, support for patient transportation, and assistance for a peaceful death. |

| 9 | The cardiovascular intensive care unit nurse’s experience with end-of-life care: A qualitative descriptive study/Calvin AO, Lind CM, Clingon SL | USA/2009 | Intensive & critical care nursing | Qualitative descriptive study | Surgical ICU nurses. N = 19 participants | To understand ICU nurses’ perceptions of their roles and responsibilities in end-of-life care. |

Nurses feel they are “walking a thin line” between providing comfort and prolonging life, with a sense of moral distress when they are unable to provide comprehensive care. There is pressure from medical doctors to continue interventional treatment, even when it is clear the patient is dying. Nurses need more support to manage the emotional and psychological demands of providing end-of-life care, such as training, counseling, and other services. |

| 10 | Palliative care needs of patients with neurologic or neurosurgical conditions/Chahine LM, Malik B, Davis M | USA/2008 | European Journal of Neurology | Retrospective review of medical records | Elderly people aged 70 on average. N = 177 participant cases | To examine the CP needs of elderly patients with neurological and neurosurgical conditions. |

The establishment of comfort measures, including the start of morphine administration, the identification of candidates for PC, and the establishment of advance directives. Patients with neurosurgical conditions have a high prevalence of symptoms such as dysphagia, pain, dyspnea, generalized weakness, and dysarthria. |

| 11 | Weaning readiness and fluid balance in older critically ill surgical patients/Epstein CD, Peerless JR | USA/2006 | American Journal of Critical Care | Prospective cohort | Elderly people aged from 60 to 87 N = 40 participants | To develop a clinical profile of elderly patients successfully discharged from prolonged mechanical ventilation. |

Critically ill patients undergoing surgery can be discharged from ventilator use and PC can guide the process through their principles of symptomatic management. Performing fluid balance, in addition to examining and supporting patients and their families, are the main nursing actions. |

| 12 | Palliative care in the surgical ICU/Mosenthal AC | USA/2005 | Critical Care Medicine | Literature review | Number of participants not stated | To raise awareness of the importance of PC in surgical ICUs. |

The administration of opioids, assistance in the preparation of PC protocols, attention to the routes of medication administration, reducing the number of routine nursing procedures as far as possible, e.g., turning, suctioning, manipulation of intravenous catheters, blood collection, and checking vital signs frequently, are all actions mentioned in the study. Healthcare professionals should receive training and education on PC so they can provide the best possible care to their patients. |

| 13 | Nursing older dying patients: Findings from an ethnographic study of death and dying in elderly care wards/ Costello J | USA/2001 | Journal of Advanced Nursing | Ethnographic research | N = 74 elderly patients N = 29 nurses N = 8 medical doctors | To explore the experience of terminally ill patients and nurses working with elderly patients in the management of end-of-life care. |

Terminal care for some elderly patients remains hampered by the reluctance of nurses and medical doctors to be more open in their communication about death. Hospital culture and the customs, beliefs, and ideologies that emanate from the biomedical model significantly shape the experiences of terminally ill elderly patients. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Of the 13 articles selected, in terms of methodological design, most were exploratory quantitative or qualitative studies (30.76 %) and literature reviews -either systematic or integrative (38.46 %). Regarding where the research was conducted, most studies were from the USA, with a total of 10 (76.92 %).

The total population of this scoping review, considering all the studies included, totaled 10,417 people, consisting of 10,331 unique patients, 78 nurses, and eight medical doctors. The patients' ages ranged from 60 years to a maximum of 109 years (study 10).

The nursing interventions cited the most in the articles were, in the first place, the establishment of physical comfort measures, such as symptom management and the administration of opioids, as well as the reduction of care activities considered unnecessary, with seven (53.84 %) studies addressing these topics. Seven publications (53.84 %) also cited the need for communication and biopsychospiritual support from nurses toward patients and their families, highlighting the importance of this item for care.

A total of three (23.07 %) studies addressed the ethical dilemmas of PC, such as nurses facing moral anguish due to the impasse between recognizing the imminence of death and following medical protocols. Or dilemmas such as nurses' inability to empathize with palliative patients, failing to reach a position of support and understanding.

Three other studies (23.07 %) addressed points such as the need to establish operational protocols for better management of procedures and the nursing team's need for training in PC. Two articles discussed the establishment of advance directives of will, the establishment of a chain of care transfer as a means of dehospitalizing palliative elderly individuals, referring them to hospices or to their own homes.

Lastly, a set of five (38.45 %) studies individually addressed other topics related to the theme, such as patient eligibility, the issue regarding the costs incurred in a situation of clinical mismanagement, the proposal of a preoperative structure with nursing appointments, a protocol for early ventilator discharge, and care for an adequate end-of-life situation.

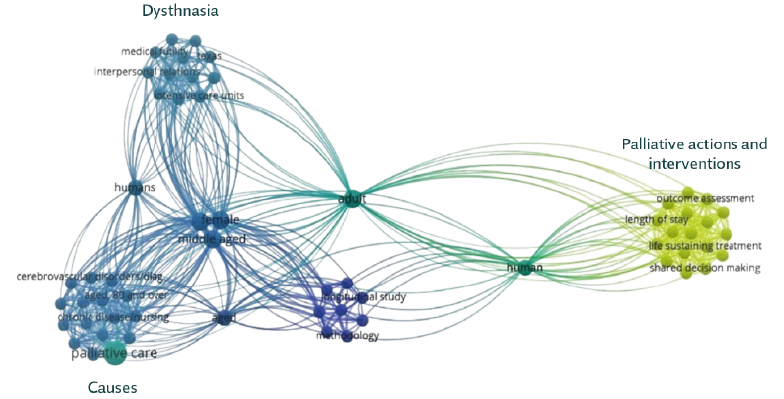

Figure 2 presents the frequency and grouping of the most recurrent keywords in the 13 studies. The studies were fully imported into the VOS viewer software, analyzed bibliometrically, and grouped by similarity, trend, recurrence, and time in the form of networks. The groups highlighted refer to dysthanasia, the causes that lead patients to PC and, lastly, palliative nursing actions and interventions.

Discussion

Regardless of the fact that the discussion on PC dates back to the 1960s, it is essential to highlight its relevance as a basic, structuring, and humanizing guideline for end-of-life care, as well as to emphasize that it will take a long time for it to be fully implemented in a surgical setting 1,27-29.

Therefore, from the analysis of this review's results, it is clear that some points central to PC need to be promoted when compared to overpowering variables, such as population aging and the number of people living with progressive chronic diseases with no prospect of a cure.

First of all, it is necessary to consider the inequality in access to this type of care and its reach in population terms, which has occurred mostly in the planet's most developed regions. This review's results show this disparity based on the volume of scientific production stemming from North America and Europe, a fact corroborated by Andrade et al. 30, who state that most of the high-evidence studies come from the USA, Canada, and the United Kingdom, which are wealthier and have a wider reach in terms of palliative care 16.

In this sense, the scope of care in demographic terms is clearly difficult in less developed regions. In the USA, for instance, 20,000 of the world's 100,000 palliative care services exist, with an increase of 267 % in 20 years (from 1985 to 2005 [1, 2, 31, 32]). In Latin America, 1562 palliative care services currently exist for a demand of approximately 12 million people who need this type of care 33,34. However, only 10 % of these people have access to this type of care, i.e. 2.6 services for every million inhabitants 2,16.

In Brazil, this ratio is of just 0.96 teams per million inhabitants, and according to the European Palliative Care Association, 20 services per million people are recommended 16,33. Although incipient, this scenario does not necessarily mean that PC will no longer be provided. However, situations involving coping with death would be better handled in the presence of specialized teams. In addition, suppressed demand, social inequalities in health, and limited access to opioids and palliative services mean that the quality of death in the country is considered poor. In a ranking of the quality of death in 81 countries, Brazil ranked 41st, behind neighboring countries such as Chile (27th), Argentina (32nd), and Uruguay (37th [35]).

With that said, the first point to note from this review's results is the management of physical symptoms and pain, which is vital to the quality of end-of-life care. Pain management is the most relevant topic when it comes to minimizing the suffering of PC patients and, in this regard, the availability of analgesic medication is inadequate in Brazil and most parts of the world due to concerns regarding illicit use and drug trafficking 36-38.

In the symptomatic context, which also includes dyspnea, nausea, delirium, and fatigue, nurses must make adequate assessments and use their knowledge to responsibly administer medication such as opioids, which are the basis of analgesic treatment in palliation (36, 39). Studies 40,41 show that in the administration of opioids, such as morphine, codeine, and fentanyl, the presentations and administration routes are factors that trigger doubts in nurses, who have this deficiency at the heart of their training. Kulkamp, Barbosa, and Binchini 42 state that myths such as the uncertainty of dosage, fear of addiction, tolerance and/or side effects of opioids often lead nurses to be reluctant to administer them.

It should be noted that poorly managed pain generates costs, is debilitating, and terrorizes patients and their families, affecting their physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. The American Pain Society and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network found that nurses had low or moderate knowledge in a survey on pain management, which shows that their knowledge in varying contexts is still deficient and needs to be improved 43.

Recently, studies on the use of alternative therapies for symptomatic management have proven promising 44,45. As it is a multidimensional phenomenon, pain deserves to be addressed from various perspectives and with a multi-professional approach. Acupuncture, acupressure, reflexotherapy, logotherapy, and phytotherapy are the main alternative therapies used, with special emphasis on the use of cannabinoid derivatives, which have been efficiently reported in recent studies with anti-emetic, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties, and may be beneficial in the palliative treatment of perioperative cancer pain and psychic disorders 46.

Another key dimension of discussion according to the research results is the cultural one, namely the permeability of PC in the surgical setting, especially in terms of patient eligibility and the early start of the palliative approach. The growing complexity of critically ill surgical patients creates an ideal opportunity for early integration into continuous care 47.

Thus, it is worth mentioning Bonnano's study 48, which compared the care provided in the traditional model and in the early PC model, in which the group that received palliative care had better self-assessments of quality of life and lower scores on scales measuring mood disorders. In addition, these patients lived on average three months longer than the group that received care in the traditional model and, as a result, plenty has been studied and it is increasingly proven that early palliative care has a positive impact on patients' lives 48.

One intervention cited in the results is the study by Walling et al. 49, which simulates a clinic model incorporated into preoperative care, in which a trained nursing professional provides specialized outpatient care, immediately prior to the medical consultant, allowing direct referrals and assistance focused on end-of-life care. This model is currently used in several US oncology clinics and is growing in other specialties, notably in cardiology and surgical oncology.

Other interventions that could benefit patients in preoperative care are those aimed at characterizing the patient's profile, their possible eligibility for PC, the creation of a personalized care plan, and the establishment of advance directives to provide an additional level of perioperative palliative care.

In the meantime, the nursing field needs to work on dissociating itself from a purely technical and prescriptive care practice towards an emphasis on the person, on solidarity, on optimizing the quality of life by discussing each patient's general care objectives and thus devising a transition plan for home care and nursing homes 27,50. The findings of this review indicate that in some cases, surgical nursing procedures -punctures, test collections, decubitus changes, invasive monitoring, ICU blood glucose checks, and intensive care maintenance- are considered unnecessary from a palliative point of view and could be postponed for the benefit of the client's well-being at the time, are routine and performed unquestionably by the team 51.

A care transition plan, as mentioned above, combined with educating families and raising awareness of actions in line with the patient's needs and wishes, promotes these elderly people's de-hospitalization when possible, significantly improving their quality of life and their perception of the end of life. Dyar 52 corroborates the above by stating that, despite all the efforts involved, the quality of dying in a hospital remains poor and, in this regard, the transfer of care and de-hospitalization provide quality and a new meaning to the end of life.

These simple perspectives can make a significant difference. Diverging from a curative, bio-technical, and disease-focused conception is crucial to generate subsidies that provide the best way to live in terminality when one is in the shadow of a reserved diagnosis. In this context lies the colossal cultural challenge posed by the perioperative environment, in which a strong paternalistic pressure is present 33,53.

Data from this review show the conflicts faced by nurses in their role as autonomous providers and patient advocates versus their protocol role in technical healthcare 54. According to Elpern, Covert, and Kleinpell 55, nurses generally perceive medical doctors as the legitimate initiators of this discussion, as well as the final decision-makers. However, in the surgical clinic setting, there is a significant obstacle to communication and dialog with medical professionals, who strangely persist in the misconception of reducing palliative care, resulting in patients being isolated behind a wall of words or in silence and preventing therapeutic adherence and the sharing of fears, anxieties, and concerns 56.

Therefore, several professional nurses find themselves in a difficult situation when they have to follow invasive protocols despite knowing that they are inconsistent with the patient's health condition 54. Faced with their prognostic awareness, the veiled distress of the families and the medical position, this results in moral an guish suffered by this professional category in their practice in palliation settings 54,55.

In the same issue, there is also the reluctance of nurses to communicate information regarding the patient's condition, which, without correct strategies or in a purely empirical way, leaves them in the dark concerning the diagnosis of their condition 50. Thus, another categorized dimension emerges from this review's results: that of nurses' communication regarding elderly patients' condition in clinics and surgical ICUs.

Some nurses find it extremely difficult to talk to patients and their families about their condition, restricting the discussion to purely technical aspects or empirical approaches that reproduce cultural preconceptions. According to Oliver et al. 57, the greatest aspect to overcome in terms of communication is truthfulness and an unwillingness to engage meaningfully with patients on sensitive issues. Studies have discussed the problems associated with providing care to dying patients and found trivial issues related to truthfulness and unwillingness to engage meaningfully in discussions with patients about death 55,57,58.

Nurses are generally skilled at providing care, managing physical symptoms, and controlling the environment, as their Night-ingalean heritage is based on basic human needs, so they provide responsible perioperative care. However, they fall short in aspects such as emotional involvement with patients, institutionalized non-disclosure of information about the process of death and dying, and reluctance to be more open in their communication 54,59. Despite the improvements made in the provision of individualized care for dying patients, their care does not seem to overcome some of the most important aspects, such as communication 59.

The applicability of PC in a surgical environment in the nursing field is also limited for other reasons. One of them is the lack of understanding and integration into biological scenarios. Several nurses have limited knowledge about the role of PC in surgery, which results in late or inadequate provision to patients in this condition 60.

Therefore, it is necessary to train these professionals in PC through education programs aimed at providing collaboration, so that they can work collaboratively with the surgical team, ensuring holistic care for surgical patients and facilitating effective communication and decision-making 60. In addition, it is necessary to provide ethical decision-making training to them, with frameworks and principles to address dilemmas to balance patient autonomy, beneficence, and non-maleficence 47. Finally, training in communication skills is also needed, including how to handle bad news, discuss treatment options, and facilitate end-of-life directives. These are implementations that can increase their ability to communicate sensitively and empathetically with patients and their families.

Finally, the process of synthesizing this review's findings was relatively hindered by the scarce evidence on interventions to introduce or improve PC in surgical patients, in addition to being limited by methodological approaches, in which rigorous and standardized evaluations are needed that also measure significant results for patients. However, all the studies presented results that satisfy the proposed practice and contribute to its implementation.

The models aim to integrate perioperative approaches and reiterate the need to rethink healthcare in an attempt to foster more socially connected, planned, and person-centered care.

Conclusions

It is known that elderly people with serious illnesses with surgical referrals can benefit from a specialized approach to PC in the perioperative setting. This review aims to describe and systematize the methods and practices used by the nursing team to provide PC to elderly patients in a highly technical environment, with hard technologies and a high expectation of recovery: the perioperative period.

There is a need to improve nurses' knowledge in the administration of opioids and alternative technologies to manage pain. There is also a need to empower these professionals to participate in ethical decisions, devise a plan aimed at transferring care, and train them to communicate more effectively with patients and their families. Through clear criteria and to reduce bias in the collection and selection of references, the data compiled in this review will contribute to strengthening actions aimed at the person, symptoms, and communication, which are commonly used in care management in the biopsychosocial and spiritual spheres.

Notwithstanding the above, this study does not end in itself but rather sheds light on the need for more studies aimed at understanding the needs and priorities of the capillarization of PC as an effective practice in a surgical setting and understanding the structural inequalities in the provision of this type of care. Thus, it constitutes a starting point for re-signifying not only healthcare in particular but also the dimension of care as a whole.