I. INTRODUCTION

Women in the business sector have been a subject of debate in the last decade, considering their rapid growth in the industry, especially in the service sector (Naidu & Chand, 2017; World Bank 2014). This was to be expected, for years the organizational development has led to an increase of 40% of jobs obtained by women since 1997 in the United States; however; the when it relates to positions of management, they were not as favorable (Bajdo & Dickson, 2001).

Meanwhile, in Mexico, 43% of women of 14 years of age or older were part of the Economically Active Population (EAP), a fact that is contrasted with the participation of men, which was of 78%, according to data published by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, 2012). It is important to note that women in OECD countries earn 16% less than men (OECD, 2013); on the other hand, Mexico ranks number 83 out of 135 countries in the last Gender Gap report (World Economic Forum, 2013).

Then again, it should be noted that Small and Medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) constitute the majority of the economic entities in the country. In the last censuses carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) in Mexico, more than 90% of the companies corresponded to this segment, being the micro-enterprises the stand out from the business units, taking as a base the classification made by the Official Journal of the Federation (DOF, 2009). The participation of women in paid work is lower than that of men. Out of every 100 people who contribute to the production of goods and services in a wage-earning capacity in non-agricultural activities (industry, commerce and services), 42 are women and 58 are men (INEGI, 2018).

In this same order and direction as the above, culture as a concept of study has its origins in anthropological studies; such is the case of the British man Edward Tylor, who was the first one to study the variable in depth, and defined it as " that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society "(Tylor, 1871, p. 1). In relation to the latter, different positions that tried to explain this variable arose. For Merton, Weber, Durkheim and Marx, quoted by Alexander and Seidman (1942), the study of culture comes from the social, not from an anthropological approach, as stated by Tylor; in contrast, Parsons (1968) focuses on the culture of action, established by the symbolism that it represents. For its part, Geertz (1989) carries out a conceptualization of culture through the human being; and finally, Luhmann (1997) analyzes a historical conception based on changes through time.

The study of culture has also been analyzed from the organizational approach, through models that try to explain the elements that intervene in organizations; therefore, it is possible to mention those exhibited by Allaire and Firsirotu (1992), Denison (1991), Hofstede (1980), and Schein (1988). The latter mentions as symbols, people-characters, rituals, and values fundamental factors of culture that can program it into the mind of a person. Some of the precursors can be seen below (see Table 1).

Table 1 Authors and their studies on organizational culture

Note. Source: Adapted by Calderón, Murillo and Torres (2003).

In relation to the dependent variable, there are several theorists who have defined the concept of competitiveness, from the capacity of supply and opportunity costs presented by Freebairn (1986), the competitive advantage over competitors by Grant (1991), the effectiveness and efficiency of competing organizations that Barney manifests (2001), and the attributes of the environment through production, demand, structure, strategy, and competition (Porter, 1991).

On the other hand, Powell and Eddleston (2011) consider that women can generate greater profits in companies. In their research, García, García and Madrid (2012) identified that women have a preference for positioning themselves in the service sector with greater opportunities for employment and development.

In this sense, Rujano and Lunar (2010) found evidence that women perform relevant roles in different positions within public organizations related to tourism (Spain), participating in the achievement of organizational objectives in 90% of the cases. Similarly, the representatives of these organizations mention that women are identified in the participation of these objectives more than men, proving to have sufficient competence to perform their duties. They have a positive attitude in the development of their activities, teamwork, as well as good interpersonal relationships.

Minguez-Vera and Lopez-Martinez (2010), quoted by Tresierra, Flores and Samame (2016), mention a positive effect of the participation of women on the performance of an organization, specifically, the insertion of women in both large and small enterprises is due to lower financial risk; they consider that greater participation of women can lead to high interest in job applications, attracting highly experienced professionals; another reason is that they believe that diversity generates an increase in creativity and innovation.

Therefore, Aristy (2012) quotes Al-Mahrouq (2010) and Lin (1998), who agree that the determinant factor for the success of SMEs is the human factor; what is essential is to identify the capacities of each one of them for the success of the organizational and individual objectives.

Evidence has been found of works that study gender and its cultural contributions, for example in rural areas (Ajadi, Oladee, Ikegami, & Tsuruta, 2015), in voluntary organizations in Italy, whose hypothesis are oriented towards the study of the organizational culture and its relation to acceptance, participation, and the rules and the flexible environment for this type of organizations to sustain themselves (Maran & Soro, 2010). It is important to highlight the influence that women have in directing organizations and gender equity practices and values that emphasize human orientation to the contribution of a competitive organization (Bajdo & Dickson, 2001).

It is a fact that organizational culture can affect the competitiveness of companies. It is influenced by the management level that is carried out by executives, through strategic decision-making (Kamoche, et al. 2015) and the impact that the study of culture and competitiveness strategies applied to Mexican industry can generate (Solis, Romero & Solis, 2014); therefore, there is a rigid and hierarchical culture regarding marketing policies.

Based on the above, the following question arises/ What is the relationship, and the influence, of the organizational culture and, and on, the competitiveness of women-led SMEs in the municipality of Cajeme, Mexico?

According to the literature and empirical evidence of the variables, the following assumption of research is proposed:

H1: Organizational culture is related to, and positively and significantly influences, the competitiveness of women-led companies in Cajeme, Mexico.

Ho: Organizational culture is neither related to, nor does it positively or significantly influence, the competitiveness of women-led companies in Cajeme, Mexico.

II. METHODOLOGY

A quantitative methodology was used to achieve the objective of the study, via a non-experimental cross-sectional design in a single time. The population to be investigated were SMEs in the commercial, industrial, and service sectors of Cajeme, Sonora, Mexico; a sample was selected using a non-probabilistic, intentional type sampling method. For the analysis of data, these were represented by numbers, which were analyzed by means of descriptive and inferential statistics.

The data was collected from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI 2009) in its National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE), which has a total of 1,409 organizations; later through a non-probabilistic sampling of intentional type, a sample of 300 companies was selected, of which 43% were directed by women, specifically 129 with women as managers, and those are the ones that were analyzed for the present project. In relation to the instrument, it is composed by two measuring scales of a five point Likert type, and each thematic addresses various items, for example: the organizational culture is considered from the organizational area with a number of six items, which are indicated from item 1 to 6 with the dimensions of values, beliefs, market, and leadership; on the other hand the competitiveness was analyzed by seven items where they intervene: target market, market trend, growth, economic policy, permanence, suppliers, and competition.

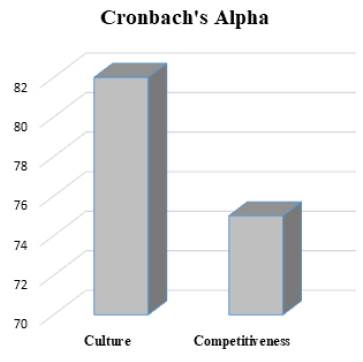

Internal validity of the instrument was carried out through the application of various tests of normality. The reliability test was applied to the data in which the items of both variables exceed the parameters established by Cronbach (see Figure 1).

As shown in the previous figure, both variables are acceptable in terms of the proposed parameters by Cronbach. Organizational culture scale is the one that has the greatest projection with a .82, and competitiveness is shown with a reliability of .75.

III. RESULTS

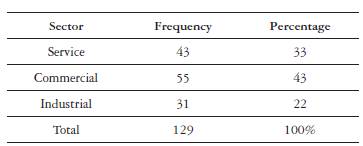

In the first instance, the descriptive aspects are highlighted, in which the different sectors that control the women in the companies of the locality are presented (see Table 2).

In the previous table, it is appreciated that women venture more into the commercial sector, since most of the SMEs that dominate that business area in the region aspire to be proficient through the leadership of women that favor the sales market, product marketing, beauty, etc.

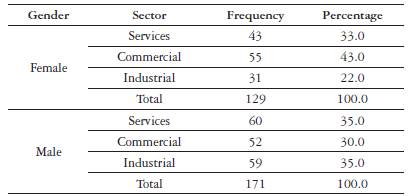

Other results related to the above, is the comparison between genders. A gendered difference in the management of the companies is noticeable, considering that the industrial sector and the appreciation of the commercial sector in a balance among the response rate (see Table 3).

Another interesting aspect that can be highlighted is in the management of personnel. Of the 129 companies that are run by women in the municipality of Cajeme, the category of employees indicates that for every ten workers, 7 are women; in that sense, it can be said that in this project by having female leadership or management, the support or recruitment is biased by the gender in command.

According to the hypothesis presented, a Pearson correlation test was conducted in which it is stated that both variables relate to a .567 and it is significant (see Table 4 and Figure 2).

H1: Organizational culture is related to, and positively and significantly influences, the competitiveness of women-led companies in Cajeme, Mexico.

It should be noted that the hypothesis of research is accepted because both variables relate positively and significantly; the remainder of the relationship belongs to other variables of the phenomenon, not envisaged in this project. The relationship model is then shown in a more specific way:

Similarly, in the figure above, it is shown that the culture variable influences the competitiveness variable in a 32%, which indicates that the companies that are run by women in the municipality of Cajeme, with a sample of 129, are competitive because the organizational culture has a high relationship with, and a significant influence on, its processes.

It should be noted that the linear regression is about the competitiveness in all of its items, in the same way the correlations of each one of the items are in some way low; however, there are noteworthy elements of each variable, for example: in culture, item CUL3, which deals with the internal behavior of the organization; item CUL4, that relates to the values, habits, and customs of the organization; item CUL5, that presents the historical aspects as a platform for organizational change; and from the point of view of competitiveness: the element of competition and economic policy have high standards, independently, which can interpret certain items to generate greater competition within the companies that are run by women.

This is based on the environment in which the study was carried out. Currently, in Cajeme, women are still predominantly more traditionalists, i.e., they replicate and obey the guidelines of the organization. Although, they are more orderly in their work tasks, it is important to emphasize that they handle it with representative habits and values, and this makes them competitive in the work environment against men.

Moreover, the interaction of a competent woman through the influence of the organizational culture in terms of its elements within the companies in Cajeme can be interpreted through the following formula:

Where:

y = Competence

X1= Behavior

X2= Values and Habits

X3= History

It should be noted that there may be other elements that interfere at the competitive level, such as economic policies that can open gaps and opportunities for growth, more in the industrial, than in commercial and service policies.

Regarding the main results, they can be compared with other studies associated with the analysis of culture and competitiveness strategies applied in the industry of Mexico (Solis, Romero & Solis, 2014), in which it is determined that there is a rigid culture in relation to the marketing element; in the same way, it can be observed that there are also elements of suppliers and competition that are a fundamental part of the distribution channels for the competitive companies.

Another interesting topic to discuss is what Soto (2015) raises, whose approach is related to the studies of family SMEs in Mexico; in addition, it highlights that one of the relevant issues is the influence of the founder on the organizational culture and the studies about women and their main roles within the organization. Similarly, it emphasizes that 40% of the consulted companies in this project belong to the family SME sector and in them the roles of women in management are developed.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

As final reflections, the objective of the project has been satisfactorily fulfilled. It is important to mention that the results show data that was not expected, such as the direct relationship between certain cultural aspects like the culture of clients, the permanence in the market, among other elements.

In the same way, a first phase of study of these themes is determined in the sector, in order to establish improvements, and to build models that contribute new knowledge and can explain the reality of women in the SME sector at the management level.

The results presented in this research can serve as a basis to explain the differences in the t motivations that lead to the employment of men and women, and could lay the foundations for the development of strategies chat allow to potentiate the capacities of entrepreneurs, based on their preferences and aspirations. The foregoing based on arguments by Powell and Eddleston (2011). They consider that women and men perform the functions of management in a different way.

It should be noted that this study reflects growth opportunities in terms of the study of organizational culture in general. It is recommended that, when analyzing organizational culture, to realize that it is mainly created for employees; that although it represents business values such as mission and vision, it must be ensured that they are adapted to them, just as the women in the sample of 129 SMEs in the region do.

It is important to recognize that 43% of the SME population is directed by women to a level of competence that is influenced by cultural aspects full of values and behavioral habits. Therefore, it would be interesting to compare a similar study with other variables and to reach closer results to explain the phenomenon in its full magnitude.