During the acculturation process individuals are inclined to maintain their cultural heritage and identity as well as to engage with their host nationals and take part in the host society (Berry, 1997). With cultural maintenance on the one hand and contact and participation on the other hand, four different acculturation strategies emerge that not only refer to the attitudes of migrants, but also to the behaviors they exhibit in their everyday lives in their new country of residence (Berry, 2005; Ward & Kus, 2012). These acculturation strategies are integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization. In brief, integration reflects a strong orientation towards both maintaining the heritage culture and interacting with the host culture; marginalization reflects a detachment from both; and separation and assimilation represent a strong orientation to only the heritage culture or host culture, respectively.

The framework of acculturation strategies proposed by Berry does not explicitly refer to the motivational underpinnings that drive individuals to maintain their culture, and to seek contact with the host nationals and participate in the host culture. Berry (1997) refers to the extent to which “cultural identity and characteristics [are] considered to be important” (p. 9) and the extent to which people “strive” for cultural maintenance. He outlines that some people “do not wish” to keep their cultural heritage, but “seek daily interaction” with the host culture. Some may “wish to avoid” contact with other cultures and “place a value” on their heritage culture. However, there is no unequivocal linkage with motivational underpinnings.

Indeed, while a large body of research has investigated the psychological processes that underlie the migration process and its effects on individuals (e.g., Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006), there is a lack of acculturation research that focuses on the motivations underpinning the behaviors of immigrants, which ultimately affect their adaptation in the new country of residence (Gezentsvey & Ward, 2008). It seems clear that the motivations that drive the behaviors through which people engage in cultural maintenance or cultural contact deserve closer investigation. We advance the idea that two distinct motives underpin acculturation behaviors.

Motivations Underpinning Behaviors during the Acculturation Process

We argue that the Motivation for Cultural Maintenance (MCM) and the Motivation for Cultural Exploration (MCE) underpin acculturation behaviors. MCM refers to immigrants’ underlying need to keep an enduring link with his or her own cultural heritage to facilitate the maintenance of a stable psychosocial organization (in terms of a sense of self and identity concerns). In contrast, MCE refers to immigrants’ underlying need to explore the host culture and to be open to new experiences in order to integrate novel cultural knowledge into the psychosocial organization (in terms of broadening one’s own self and identity).

Grounding MCM and MCE in the Motivational Literature

We contend that MCM and MCE are two important and distinct pathways in understanding acculturation behaviors and the resulting adaptation of immigrants, and that these motivations are theoretically linked to other core motives and related constructs. This section focuses on three main areas of motivational research.

Core motives. One strand of the contemporary literature on motivation proposes the five core motives of trust, control, understanding, self-enhancement, and belonging (Fiske, 2008), and the last three have clear conceptual links to MCM and MCE. People strive to understand their social environment because they want to obtain a “coherent, socially shared understanding” (Fiske, 2008, p. 12) of what is going on around them, as this shared understanding helps people to predict others’ actions, to assess situations quickly, and to create a common view of the world. The self-enhancement motive refers to preserving self-esteem or to continuing self-improvement. Finally, belonging is an omnipresent motivation to form enduring and close bonds with others that affects cognition and behavior (Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

The understanding motive may very well drive immigrants to maintain their heritage culture in a new cultural environment and to preserve shared practices with their ethnic peers. At the same time, the desire for understanding can drive immigrants to gather information about the host culture to create new shared practices with national peers. Migrants’ self-image may be threatened by the experience of not quite fitting into the host society. To restore their positive self-image, they may choose to maintain their culture and favor their ingroup (i.e., migrants of the same heritage culture) above the outgroup (i.e., members of the host culture), or may self-enhance by trying to fit into the host culture and meet public expectations. The belonging motive might drive immigrants to maintain a sense of belonging to one’s original cultural ingroup while also facilitating a new sense of belonging to the host culture.

A motivational continuum. Ryan and Deci (2000a) proposed in their Self-Determination Theory that “to be motivated means to be moved to do something” (p. 54), and that at the most basic level there is a distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. Although individuals who are extrinsically motivated engage in an activity to reach a certain goal or outcome, intrinsic motivation drives individuals to engage in an activity for the sake of the activity, for the pleasure one experiences while doing it, and the satisfaction one gets from that activity.

Ryan and Deci’s (2000b) definition of intrinsic motivation as the human “tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise one’s capacities, to explore, and to learn” (p. 70) is particularly relevant for understanding MCE. Migrants may want to explore their new environment for the sheer enjoyment of experiencing something novel or because they want to broaden their horizon. At the same time, the motivation to explore new cultures may serve specific purposes (e.g., migrate to find better educational opportunities for children), indicating that MCE may also lead to the fulfilment of extrinsic gains. The links between Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000a) and MCM seem to be less obvious, but this theory also argues that relatedness is one of the basic human psychological needs, and that affiliation is a life goal that is intrinsically motivated (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Therefore, MCM might be intrinsically driven because it establishes an affiliation with one’s heritage culture and its members.

Cognitive theories of motivation. In the 1980s researchers acknowledged that cognition and motivation should not be seen as independent of each other but as intertwined (Sorrentino & Yamaguchi, 2008). Two cognitively-based motives are particularly relevant for the present research. Novelty-seeking (or the desire for novelty) refers to individuals’ tendency to approach rather than to avoid novel situations (Pearson, 1970). Need for closure refers to individuals’ desire to get clear and straightforward answers to questions and ambiguity avoidance; individuals may experience negative feelings when closure for open questions is not attained and positive feelings when closure is achieved (Kruglanski & Webster, 1996).

Novelty-seeking appears to be related to MCE because this motivation drives openness to new experiences, which might be reflected on the need to explore the host culture, and a willingness to approach rather than to avoid the host culture. Inquisitiveness about the environment also appears to be a facet of both constructs. In contrast, individuals who have a strong need for closure and a strong motivation for cultural maintenance may approach life in similar ways. For example, individuals with a strong MCM focus on preserving a link to their cultural heritage, maintaining a stable sense of self, and creating a safe and familiar cultural environment. Just as someone who has a strong need for closure, individuals with a strong motivation to maintain their heritage culture may be less prepared to consider new perspectives and to incorporate novel ways of looking at the world into their thought patterns.

Maintenance versus Exploration in the Broader Psychological Literature

In addition to links with the broad motivational literature, cultural maintenance and exploration motives also seem to reflect a fundamental interplay identified in diverse research traditions between the need for stability and the need to be open to new experiences.

To illustrate, Schwartz’s (1992) distinction between basic values that focus on conservation versus openness to change, Higgins’ (1997) distinction between regulatory focus on prevention versus promotion, Rothbaum, Pott, Azuma, Miyake, and Weisz’s (2000) distinction between proximity versus exploration in relationships, as well as DeYoung’s (2006) stability versus plasticity personality traits, all refer to a dichotomy of maintenance versus exploration related to the motives proposed in the present research. Motives that refer to conservation, maintenance, and stability are reflected in MCM, whereas motives of openness to change, exploration, and plasticity are more likely to be reflected in MCE.

Links between Acculturation Motives, Acculturation Behaviors, and Adaptation

The motivation to maintain a feeling of belonging to the heritage group is likely to influence whether acculturating individuals prefer to socialize with their ethnic peers (maintenance) or with host nationals (exploration). The motivations to maintain and to explore are thus reflected in corresponding behaviors and ultimately in the way migrants behave towards their own community, as well as the broader host society.

Adaptation of immigrants to the host society covers two main domains (Searle & Ward, 1990): psychological adaptation (an affective domain concerning well-being/satisfaction that immigrants experience when settling in the host culture) and sociocultural adaptation (a behavioral domain concerning immigrants’ ability to negotiate life in the host culture and to ‘fit in’). Studies have shown that immigrants’ patterns of contact with ethnic or national peers affect their adaptation outcomes: ethnic peer connections increase psychological adaptation (Vedder, van de Vijver, & Liebkind, 2006), whereas national peer connections increase sociocultural adaptation (Li & Gasser, 2005). Consequently, there appears to be a clear link between what immigrants do during the acculturation process (e.g., their patterns of socialization) and their sociocultural and psychological adaptation.

Several studies have shown that there is a link between the behaviors that migrants engage in and their sociocultural and psychological adaptation outcomes. In particular, migrants’ contacts with national or ethnic peers influence these outcomes. Vedder et al. (2006) used a structural equation modeling approach to analyze data from the Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition (ICSEY) study, which surveyed almost 8 000 adolescents from 13 countries. They found that ethnic peer contacts predicted psychological adaptation but not sociocultural adaptation. These results indicate that having contact with ethnic peers positively affects psychological well-being but not the learning of the new skills necessary to adapt successfully to the new cultural context (unless ethnic peers know the “rules” of the host country and provide informational support).

Similar findings were obtained by Ward and Kennedy (1993) in their study with 145 Malaysian and Singaporean university students in New Zealand; among other factors, satisfying relationships with ethnic peers were predictive of psychological adjustment. Along the same lines, strong identification with ethnic peers predicted less depressive symptoms (i.e., better psychological adaptation) in a sample of 98 sojourners in New Zealand (Ward & Kennedy, 1994).

Although interactions with ethnic peers predict psychological adaptation, research has shown that contact with national peers predicts sociocultural adaptation. For example, Ward and Kennedy (1993) found in their previously mentioned study that the quantity of interactions with host nationals was predictive of sociocultural adaptation. These findings were supported by the results of the second part of their research with 156 Malaysian university students in Singapore. Similarly, Li and Gasser (2005) conducted a study with 117 Asian international students in the US and found that contact with host nationals was a predictor for sociocultural adaptation. Host national contact may have led to an increased understanding of “how things work” in the host country and may have equipped migrants with the skills necessary to adjust effectively. Ward and Kennedy (1994) also found that a strong identification with national peers lead to better sociocultural adaptation.

The Present Study

Based on the theoretical and empirical review presented above, we argue that motives that refer to conservation, maintenance, and stability are reflected in MCM, whereas motives of openness to change, exploration, and plasticity are reflected in MCE. More importantly, we argue that having a high (or low) focus on maintenance or exploration motives appears to be relevant for acculturating individuals. These motivations should also influence the two main questions that arise for acculturating individuals (Berry, 1997): to what extent do they want to maintain their cultural heritage and identity, and to what extent do they want to maintain a relationship with the host group.

Previous research has shown that specific behaviors—and particularly peer connections—influence the psychological and sociocultural adaptation of immigrants in the host country. The motivations to maintain and to explore should influence corresponding behaviors and ultimately the way that immigrants behave within and towards the host society as well as their own community. The present study provides an initial test of these theoretical contentions in the context of peer connections. We test whether immigrants’ maintenance or exploration motivations influence acculturation behaviors related to peer connections, which in turn influence sociocultural and psychological adaptation.

We test five specific hypotheses. First, we argue that MCM and MCE will predict specific acculturation behaviors. Cultural maintenance behaviors facilitate and safeguard a link with the heritage culture. For example, individuals may prefer to socialize with ethnic peers to maintain links with their heritage culture (e.g., language, normative behaviors, national celebrations, food). Conversely, cultural exploration behaviors facilitate the exploration of the host culture and individuals’ participation in it. For example, individuals may seek more interactions with host nationals than with their ethnic peers to learn a new language and explore different normative behaviors, celebrations, and food.

Hypothesis 1.1: There is a positive path between MCM and connections with ethnic peers.

Hypothesis 1.2: There is a positive path between MCE and connections with national peers.

Second, we theorize that both types of acculturation behaviors—and in particular acculturation behaviors related to peer connections, which are driven by MCM and MCE as outlined above—impact the psychological and sociocultural adaptation of individuals to their host culture.

Hypothesis 2.1: There is a positive path between connections with ethnic peers and psychological adaptation.

Hypothesis 2.2: There is a positive path between connections with national peers and sociocultural adaptation.

Finally, we are proposing a mediation model in which individuals’ cultural motivations influence acculturation behaviors, which in turn influence sociocultural and psychological adaptation in the host culture.

Hypothesis 3: Acculturation behaviors related to peer connections will mediate the influence of MCM/MCE on adaptation outcomes.

Method

Procedure

An online questionnaire using SurveyMonkey technology was conducted. Participants were recruited by snowball sampling with the assistance of various organizations. New Zealand organizations (e.g., Multicultural Services Centre in Wellington and the Wellington Council of Social Services, Community Sector Taskforce Wellington, New Zealand Federation of Multicultural Councils) and community groups (e.g., Afghan Association of Wellington, Assyrian Community, Auckland Finnish Society, Auckland Welsh Society) passed the link on to members of their network, and the survey link was promoted on the Diversity Issues website and online newsletters of the Office of Ethnic Affairs and Immigration New Zealand. The lead author used her own network of migrants to pass on the link to the online survey, and posted the link in the social networking sites Facebook and X-ing and an online forum for South African migrants (“SA going to NZ”).

As inclusion criteria, the participants were non-refugee immigrants in New Zealand who came to the country as adults (at least 18 years old), who have lived in New Zealand for at least six months and resided in New Zealand at the time when the survey was conducted. Participation was anonymous, and no incentives were given to the respondents. It took about 20 minutes to complete the questionnaire that was administered in the English language only.

Participants

A total of 333 participants responded to the survey. However, 50 responses were deleted because the respondents did not complete the demographic questions, which made it impossible to determine if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 283 responses, another three were excluded from the analysis because they did not fulfil the criteria for participation or gave improbable responses to the demographic questions. The final sample comprised 280 adults from 53 different countries currently living in New Zealand, who were non-refugee immigrants, came to the country as adults (at least 18 years old), and were living in the country for at least six months. A large proportion of participants (40%) were born in only five countries (Germany, Finland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Most of the participants (57.7%) self-identified as European and were female (n=181; 64.6%), with average age of 39.28 years (SD = 10.31). Participants had lived in New Zealand for an average of 8.11 years (SD = 8.85).

Materials

The questionnaire included participant information and debriefing sheets, demographic items as well as measures of the three main constructs of interest.

Motivation scales. Details about the development and pre-test of the MCM and MCE scales are reported elsewhere (Recker, 2013). In brief, a pool of items was developed taking into consideration the operational definition of the constructs.

Motivation for Cultural Maintenance (MCM) was operationally defined as the motivation to keep an enduring link with one’s cultural heritage in order to maintain a stable psychosocial organization (i.e., a person’s motivation for a stable cultural heritage). Motivation for Cultural Exploration (MCE) was operationally defined as the motivation to explore and incorporate novel cultural knowledge into the psychosocial organization (i.e., a person’s motivation for a variable/adaptable cultural knowledge).

Considering the motivational focus of the measures, other measures were considered for developing the items, including the Self-Regulation Questionnaire – Study Abroad (Chirkov, Vansteenkiste, Tao, & Lynch, 2007), the Need for Uniqueness Scale (Tepper & Hoyle, 1996), and the Need for Cognition Scale (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). Seventeen motivation-type items were developed for the MCM Scale, and sixteen motivation-type items for the MCE Scale. In the present study, we used the best items that emerged from pilot-testing and preliminary analysis resulting in a 9-item MCM Scale and an 8-item MCE Scale Items that were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example of MCM items include: “It is important to keep my cultural traditions because they are part of who I am,” and “I do not feel the need to practice my ethnic traditions” (reverse coded). Example of MCE items include: “It is exciting for me to explore new cultures,” and “Sometimes it is important for me to put my own culture into perspective and acknowledge different views.” Table 1 presents all scale items.

TABLE 1 Items of the Motivation for Cultural Maintenance (MCM) and Motivation for Cultural Exploration (MCE) Scales

Note. Scale instructions: “Read each statement and select the response that BEST describes you AS YOU REALLY ARE”. Scale items are presented in random order, and participants rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Source: own work.

Acculturation Behavior (peer connections) . Considering the importance of peer connections in the acculturation process, we used Part F of the Immigrant Adolescent Questionnaire (Vedder & van de Vijver, 2006) to measure the frequency of interaction with ethnic and national peers. The questions focused on three aspects for each of the two peer groups: close friends, and interactions at work and during spare time. The close friend questions read: “How many [Close ethnic friends (from your culture)/Close national friends (from New Zealand) do you have?”, answered on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (none) to 5 (many). The work question read: “How often do you spend time at work with [Ethnic members (from your culture)/National members (from New Zealand)]?”, answered on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The spare time question read: “In your spare time how often do you spend time with [Ethnic members (from your culture)/National members (from New Zealand)]?”, answered on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores indicate more interaction with ethnic and national group members.

Psychological and Sociocultural Adaptation . Psychological wellbeing was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) that assesses people’s judgments of their own life satisfaction (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The SWLS is a 5-item inventory with questions such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” and “The conditions of my life are excellent.” The responses are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), so that higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with life. To measure participants’ emotional wellbeing, the WHO (Five) Well-Being Index (1998 version; WHO, 1998) was used. It is a 5-item measure with questions such as “Over the last two weeks I have felt cheerful and in good spirits” and “Over the last two weeks I woke up feeling fresh and rested.” The responses are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (at no time) to 5 (all of the time), so that higher scores indicate greater emotional wellbeing.

The participants’ sociocultural adaptation was assessed using the Revised Sociocultural Adaptation Scale (SCAS-R; Wilson & Ward, 2010). The 21-item inventory includes items such as “Building and maintaining relationships” and “Maintaining my hobbies and interests.” Responses are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all competent) to 5 (extremely competent), so that higher scores indicate higher sociocultural adaptation.

Results

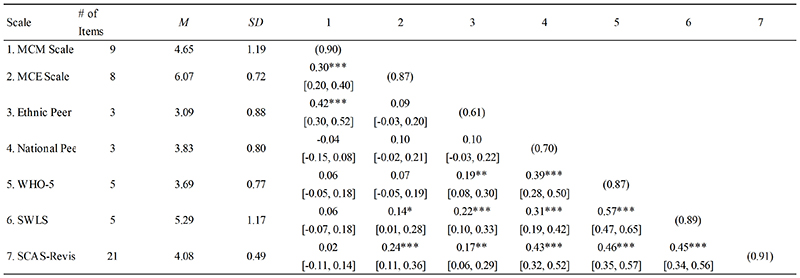

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the scales as well as their intercorrelations. All scales had acceptable levels of internal consistency, and the correlations were overall in the expected directions. (For correlations between the newly created MCM and MCE scales and other measures, see Recker, 2013.)

TABLE 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between the Measures

Note. N = 280. Numbers in brackets are 95% confidence intervals based on bias-corrected accelerated bootstrapping 10 000 re-samples in SPSS. Cronbach’s alpha are presented in the diagonal. MCM = Motivation for Cultural Maintenance Scale. MCE = Motivation for Cultural Exploration Scale. Ethnic and National Peer = three items measuring connections with ethnic/national peers as close friends, and spending time at work and during spare time. WHO-5: WHO (Five) Wellbeing Index; SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale. SCAS-R = Revised Sociocultural Adaptation Scale.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

Source: own work.

We conducted all model testing in MPlus 7.5 with robust maximum likelihood estimators. We started by examining the proposed two-factor structure underlying the MCM and MCE scales. Results from a confirmatory factor analysis indicated the two-factor model had adequate fit to the data: SBχ2 (n = 280, df = 118) = 295.99, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.073 [90% CI = 0.063, 0.084]; CFI = 0.909; SRMR = 0.068.

Considering this is the first test of our model, we included all paths (and not only the hypothesized ones) in the model. We created item parcels for the MCM, MCE, and SCAS-R scales before testing the full mediation model. Creating parcels of items has some advantages over item-level data as it creates more parsimonious models and sources of sampling error are reduced because fewer parameters need to be calculated in the model (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Considering these advantages, we report the findings using parcels, but the overall findings are similar using item-level data (available upon request). Three parcels for each of the MCM and MCE scales were created. Each parcel contains three items, except for the third parcel of the MCE scale, which only contains two items. Items were parceled in the order in which they appear on the scale; except for the two MCM-items that covaried and were put in the same parcel. Three parcels were created for the SCAS-R scale, with seven items for each parcel in the order in which they appear on the scale. We used the respective three items (close friend, spend time at work and during spare time) as indicators of the peer connection latent factors, and used the scale averages for the WHO-5 and SWLS as the observed indicators of psychological adaptation.

The mediation model in Mplus included all paths but Figure 1 only reports the statistically or marginally significant effects. The model had good fit to the data, SBχ2 (n = 280, df = 104) = 262.47, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.074 [90% CI = 0.063, 0.085]; CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.054. The model explains 49% of the variance in psychological adaptation, and 32% of the variance in sociocultural adaptation. (Adding age and years spent in New Zealand as covariates predicting all six latent variables in the model yielded virtually identical results; available upon request.)

Figure 1. Simplified structural equation model testing the strength of the relationships between maintenance/exploration motivation, peer connectedness and adaptation outcomesNote. Standardized regression coefficients are presented (STDYX Standardization in Mplus) to indicate the strength of the relationships (N = 280). Solid lines show significant paths (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001) and dashed lines marginally significant paths († p < 0.09). All other paths were modelled but excluded for not reaching significance (see full model in Appendix). Values in grey box are the variance explained (r-square).

The results provide overall support for the predicted theoretical model. First, greater maintenance motivation is associated with higher ethnic peer connections (β = 0.63, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.48, 0.78]), and greater exploration motivation is associated (albeit marginally) with higher national peer connections (β = 0.15, p = 0.072, 95% CI [-0.01, 0.31]). These results provide overall support for H2.1 and H2.2. Second, higher ethnic peer connections is associated (albeit marginally) with psychological adaptation (β = 0.21, p = 0.089, 95% CI [-0.03, 0.44]), and higher national peer connections is associated with sociocultural adaptation (β = 0.45, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.33, 0.57]). These results provide overall support for H3.1 and H3.2. Other unpredicted associations also emerged. Exploration motivation was also associated with sociocultural adaptation (β = 0.28, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.11, 0.44]), national peer connections was also associated with psychological adaptation (β = 0.53, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.38, 0.67]), ethnic peer connections was also marginally associated with sociocultural adaptation (β = 0.16, p = 0.082, 95% CI [-0.02, 0.33]).

Although two of the predicted paths were marginally significant (i.e., MCE → national peer connections, and ethnic peer connections → psychological adaptation), we tested for mediation for the sake of completeness. We used a bootstrapping mediation method to test the indirect paths with 10 000 bootstrapping and bias-corrected confidence intervals in Mplus. None of the indirect effects were statistically significant at the standard p-value level (p < 0.05) but the indirect effects with a 90% confidence interval excludes 0 in all cases, which indicates a trend in the expected directions. There is a trend for MCM to predict both psychological adaptation and sociocultural adaptation indirectly via ethnic peer connections: indirect effect = 0.10, 90% CI [0.01, 0.22], and indirect effect = 0.06, 90% CI [0.001, 0.12], respectively. Similarly, there is a trend for MCE to predict both sociocultural adaptation and psychological adaptation indirectly via national peer connections: indirect effect = 0.04, 90% CI [0.01, 0.10], and indirect effect = 0.07, 90% CI [0.01, 0.15], respectively.

Discussion

Are the behaviors and ultimately the adaptation outcomes of immigrants influenced by their motivation to maintain their heritage culture and by their motivation to explore the culture of their new country of residence? The present research provides an initial answer to this question and sheds light on this under-researched area in the psychological acculturation literature. Drawing from extant literature on core human motives, as well as on research distinguishing between motives that refer to conservation, maintenance, and stability versus motives of openness to change, exploration, and plasticity, we proposed two distinct motivation paths of acculturation behavior and adaptation outcomes.

The two motivations are labelled Motivation for Cultural Maintenance (MCM) and Motivation for Cultural Exploration (MCE). MCM refers to immigrants’ underlying need to keep an enduring link with his or her own cultural heritage to facilitate the maintenance of a stable psychosocial organization (in terms of maintaining a sense of self and identity), while MCE refers to immigrants’ underlying need to explore the host culture and to be open to new experiences to integrate novel cultural knowledge into the psychosocial organization (in terms of broadening one’s own self and identity). We asserted that immigrants’ maintenance or exploration motivations should influence their acculturation behaviors (particularly their level of connections with ethnic and national peers), which in turn should influence their sociocultural and psychological adaptation in the host culture. Results from structural equation models provide some support for this prediction and the proposed dual-process model.

Relationships between MCM/MCE, Acculturation Behavior and Adaptation

Supporting H1.1, MCM predicted ethnic peer connections, which indicates that immigrants with a strong motivation to maintain their heritage culture tend to socialize with ethnic peers. This finding suggests that the motivation to preserve one’s heritage culture influences intra-group contact and patterns of socialization. Baumeister and Leary (1995) proposed that individuals are motivated to form bonds on the basis of common interests and experiences. Thus, MCM may be an expression of the need of immigrants to belong to a familiar group in an unfamiliar cultural setting.

In line with previous findings (e.g., Vedder et al., 2006), high levels of ethnic peer connections marginally predicted better psychological adaptation, providing partial support for H2.1. In other words, there is a trend for immigrants who are high on MCM to socialize with ethnic peers, and this in turn affects their satisfaction with life and their emotional wellbeing. This finding is relevant because high life satisfaction has been linked to positive physical and mental health outcomes (Gouveia, Milfont, Fonseca, & Coelho, 2009; Pavot & Diener, 2008).

Unexpectedly, MCE was not a statistically significant predictor of national peer connections as postulated in H1.2 but predicted sociocultural adaptation directly. A potential explanation for this finding can be derived from research by Ward, Okura, Kennedy, and Kojima (1998) who found that the sociocultural learning curve has the steepest increase in the first 4 to 6 months of the acculturation experience, and then levels off towards the end of the first year. The participants of the present study had been in New Zealand for approximately eight years on average. It is possible that by that time their culture learning had progressed to a level where they did not need to seek national peer contact to facilitate their sociocultural adaptation; instead, this behavior may be more typical in the early stages of arrival.

Furthermore, stronger national peer connections were predictive of sociocultural adaptation supporting H2.2. This finding suggests that immigrants who have more frequent contacts with host nationals have developed a better ability to ‘fit in’, which means that they demonstrate more adaptive behavioral competencies and they have fewer sociocultural problems in the new cultural setting. A meta-analysis of 66 studies supports this finding by showing that the quantity of contact with host nationals is a stronger predictor of sociocultural adaptation than the quality of those contacts (Wilson, Ward, & Fischer, 2013).

National peer connections also predicted psychological adaptation. Considering that making friends and acquaintances with host nationals may give immigrants the feeling of being more settled in their new country of residence and expand social support networks, this finding can be interpreted considering research by Jasinskaja-Lathi, Liebkind, Jaakkola, and Reuter (2006), who stressed the importance of active contact with host nationals for the psychological wellbeing of immigrants.

In line with our theoretical contentions (H3), the results support a trend for ethnic and national peer connections to mediate the influence of maintenance and exploration motivations on psychological and sociocultural adaptation. However, the predicted mediation effects were only marginally significant. Future research should explore the extent to which the predicted indirect effects are confirmed in other populations. It would also be useful to explore whether other acculturation behaviors could function as mediators. The extant literature has confirmed a link between whether migrants choose to establish contact with ethnic and national peers, and psychological and sociocultural adaptation outcomes (Vedder et al., 2006; Ward & Kennedy, 1994). However, use and proficiency of the host country language also influence adaptation outcomes (Vedder & Virta, 2005). It would thus be interesting to examine whether language proficiency would mediate the effect of maintenance and exploration motivations on adaptation.

Finally, MCM and MCE showed medium-to-high correlations in our sample. It is likely that the strength of the relationship between these two motives will depend on the context. In multiculturally diverse and accepting societies like New Zealand, where migrants are encouraged to engage with both communities, MCM and MCE should show stronger correlations than in less-accepting societies. However, we argue MCM and MCE are distinct, meaning that it is possible for individuals to score independently on these motivations (i.e., high on both, low on both, or high on one and low on the other).

The Value of the Proposed Model

Overall, the results suggest that MCM and MCE have significant value within the acculturation literature. The proposed dual-process model integrates two types of processes that predict immigrants’ adaptation in a new cultural setting. In the broadest sense, the model suggests that while the motivation to preserve one’s heritage culture influences psychological outcomes of immigrants, the motivation to explore the culture of the host country impacts social learning and ‘fitting in.’ The model thus increases the understanding of the factors that influence adaptation and sheds light on the underlying mechanisms that lead to adaptation (e.g., the role of acculturation behavior).

Moreover, the starting points of the processes that are illustrated in the model are motivational drives. Because motivational theory has not played an important role in the acculturation literature thus far, the model has the potential to provide a new framework for the investigation of immigrants’ adaptation outcomes. For example, the model put what Berry (1997) referred to as “striving for cultural maintenance” and “seek[ing] daily interaction” (p. 9) with host nationals in a theoretical motivational framework that may provide a starting point for future research that investigates other motivational drives in the context of acculturation and adaptation.

The findings may also be relevant for policy makers. In some countries, there is an expectation of the majority culture that immigrants should blend in and assimilate to the mainstream, or segregate and eventually return to their countries of origin. This view is often reflected in immigration policies that are not supportive of cultural diversity. However, the current study suggests that both the motivation to maintain culture and the motivation to explore the host culture are linked to positive adaptation outcomes—at least in New Zealand. Therefore, governments would be well advised to provide a policy framework that allows and encourages immigrants to maintain their culture, while at the same time encourages them to explore the host culture.

Potentially, the findings of the present study could be used to increase the awareness of immigrants of their own motivations regarding cultural maintenance and exploration. For example, the MCM and MCE scales could be used in cross-cultural training to start discussions about the effects of cultural maintenance and exploration on acculturation behaviors and resulting adaptation.

Concluding Remarks

When considering the results and potential theoretical and practical implications outlined above, it is necessary to be aware of some important limitations. First, we only provide initial evidence for the psychometric validity of the new MCM and MCE scales. Future research should examine the psychometric properties of both scales in distinct populations. Second, it needs to be acknowledged that the sample is not representative of the New Zealand immigrant population in general. Europeans are over-represented, while Pacific Islanders and Asian immigrants are under-represented. It is possible that the observed relationships are confounded by the fact that more than half of the participants self-identified as European. For example, ethnic peer connections may be a stronger predictor of psychological adaptation under conditions of large cultural distance between home and host countries. Therefore, the findings of this study should not be generalized without replication in broader populations.

Lastly, this study is cross-sectional in nature. A longitudinal approach is more suitable than a cross-sectional approach to investigate mediation models like the one tested in Figure 1. Therefore, future research should attempt to investigate the effects of the proposed motivations on adaptation (mediated by acculturation behaviors) using a longitudinal design. Such a design will allow conclusions about the longitudinal relations and mediation effects between motivations, behavior, and adaptation. Furthermore, future research should investigate the influence of MCM and MCE on other acculturation behaviors, such as language use, that contribute to adaptation outcomes.

In conclusion, this study provides an initial test of the role of motivations in predicting acculturation behavior, and later psychological and sociocultural adaptation. The dual-process motivational model proposed here provides a useful conceptual framework for understanding the acculturation process of immigrants in a new cultural milieu.