Remark

| 1) ¿Why was this study conducted? |

| It is the initiative from Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group to consolidate the novel proposal regarding the pancreatic trauma management. |

| 2) ¿ What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| Most pancreatic injuries can be managed with a combination of hemostatic maneuvers, pancreatic packing, parenchymal wound suturing, and closed surgical drainage. |

| 3¿ What do these results contribute? |

| Pancreatic trauma treated by parenchymal wound suturing is the main strategy to preserve the primary organ function and decreasing short- and long-term morbidity. |

Background

Pancreatic trauma is a rare but potentially lethal injury because often it is associated with other abdominal organ or vascular injuries. Usually it has a late clinical presentation which in turn complicates the management and overall prognosis 1. Due to the overall low prevalence of pancreatic injuries, there has been a significant lack of consensus among trauma surgeons worldwide on how to appropriately and efficiently diagnose and manage them 2,3. But what is well known is that the surgical approach of these injuries depends if the pancreatic duct is involved or not 3,4. The accurate diagnosis of these injuries is difficult due to its anatomical location and the fact that signs of pancreatic damage are usually of delayed presentation 5,6. The classic management recommendations for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Grade III injury of the distal half of the pancreas has been a distal pancreatectomy and for AAST Grades IV and V injuries has been a formal pancreatic duodenectomy 3,4. However, the current surgical trend has been moving towards organ preservation in order to avoid complications secondary to exocrine and endocrine function loss from partial or complete organ resection and/or potential implicit post-operative complications including leaks and fistulas 7-9. The aim of this paper is to propose a management algorithm of patients with pancreatic injuries via an expert consensus.

This article is a consensus that synthesizes the experience earned during the past 30 years in trauma critical care management of the severely injured patient from the Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia which is made up of experts from the University Hospital Fundación Valle del Lili, the University Hospital del Valle "Evaristo García", Universidad del Valle and Universidad Icesi, Colombian Association of Surgery, the Pan-American Trauma Society and the collaboration of international specialists of the United States of America.

Epidemiology

Pancreatic injuries account for approximately 0.2% of all trauma cases and 3% of all abdominal trauma cases. The most common worldwide mechanism is blunt trauma caused by road traffic accidents 2. A multicenter nationwide cohort study in Japan from 2004 to 2017 found a total of 743 patients with pancreatic trauma (2.4% of all abdominal trauma) and found that 337 (45.4%) had AAST Grade I injury, 66 (8.9%) Grade II, 178 (24.0%) Grade III, 62 (8.3%) Grade IV and 100 (13.5%) Grade V 10. Also, 52.5% had concomitant severe associated injuries (liver 15.7% and vascular 15.5%). Three hundred and five (41%) received non-operative management, 70 (9.4%) had partial resection of the pancreas and 31 (4.1%) had Damage Control Surgery (DCS). The overall mortality was 14%, and the variables associated with higher risk of death were: higher AAST Grade, increased age and the coexistence of severe injuries 10. Data on pancreatic trauma in Latin-America is scarce, but what is evident is that in Cali, Colombia penetrating trauma is more frequent than in many other cities and/or countries. Our registry has shown that the incidence of penetrating pancreatic trauma is as common as blunt trauma and tends to be more severe and associated with other significant injuries. A retrospective review of our institutional experience on penetrating pancreatic trauma between 2000 and 2013 found a total of 28 patients, of which 26 were by gunshot wounds with a median anatomical severity given by the Penetrating Abdominal Trauma Index (PATI) of 50 (IQR=34.5-67.5) with a median of 5 associated injuries highlighting the complexity of these cases 11. Of the 28 patients, 6 (21.4%) had AAST Grade I injury, 9 (32%) Grade II, 5 (18%) Grade III, 5 (18%) Grade IV and 3 (10%) had Grade V injury. We found that the management of these penetrating injuries were different from prior published case series because 83% of our patients received DCS techniques, 12 (42.9%) had simple suture repair of the pancreatic laceration, 8 (28.6%) had a distal pancreatectomy and none of them underwent pancreatic duodenectomy 12.

Initial approach and diagnosis

Initial management must be directed towards the stabilization of the patient according to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines and following Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) principles. Upon arrival, the choice between immediate surgical exploration or further imaging studies is dependent on the hemodynamic status of the patient. If the patient is hemodynamically stable or a transient responder, a Whole Body Computed Tomography (WBCT) should be performed to determine the extent of the pancreatic injury and any other significant findings. The hallmarks of pancreatic injury on Computed Tomography (CT) are peri-pancreatic hematoma, retroperitoneal edema and laceration of the body of the pancreas 5,12. However, patients with peritoneal signs and/or hemodynamic instability (sustain systolic blood pressure (SBP) (90 mmHg should be transferred immediately to the operating room (OR) and the diagnosis of a pancreatic injury should be done during the initial exploratory laparotomy. Is important to note that opening of the lesser sac and direct detailed inspection of the pancreas is required to accurately stage the injury 13,14 (Table 1).

Table 1 The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) classification of pancreatic injury 25.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Minor contusion without duct injury or superficial laceration without duct injury |

| II | Major contusion or laceration without duct injury or tissue lost |

| III | Distal transaction or parenchymal injury with duct injury |

| IV | Proximal (to right of the superior mesenteric vein) transaction or parenchymal injury with duct injury |

| V | Massive disruption of pancreatic head |

Surgical management

During the initial exploratory laparotomy, the trauma surgeon should initially control all sources of ongoing surgical bleeding followed by control of sources of bowel contamination. Only then can he or she direct his or her attention to staging the involved pancreatic injury. If the patient develops hemodynamic instability during or prior to the procedure with a sustained SBP of (70 mmHg or less, regardless of aggressive DCR, the placement of a Resuscitative Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) should be considered and placed in Zone I as an adjunct 15,16. Although the management of specific lesions of the pancreas are controversial, ranging from radical approaches such as a pancreatic duodenectomy in cases of AAST Grade V injuries, it is our general recommendation to always seek preservation of pancreatic tissue, leaving resection as a last resort 8,17. The appropriate staging of a pancreatic injury of the body and tail of the pancreas can be done via the lesser sac. An injury localized at the head or uncinate process will require both the lesser sac to be opened but also a formal Kocher Maneuver to adequately evaluate the pancreatic duodenal complex (Figure 1).

When facing a pancreatic injury, three anatomical landmarks must be clearly delineated:

All pancreatic injuries can then be appropriately classified according to the criteria of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma AAST. The surgical management of these injuries as per these grades is as follows:

AAST Grade I: hemostasis and +/- surgical drainage

AAST Grade II: simple hemostasis maneuvers, if bleeding does not stop, perform pancreatic laceration repair with non-absorbable monofilament 3-0 suture (interrupted or continuous depending on surgeon’s preference) and surgical drainage (Figure 2).

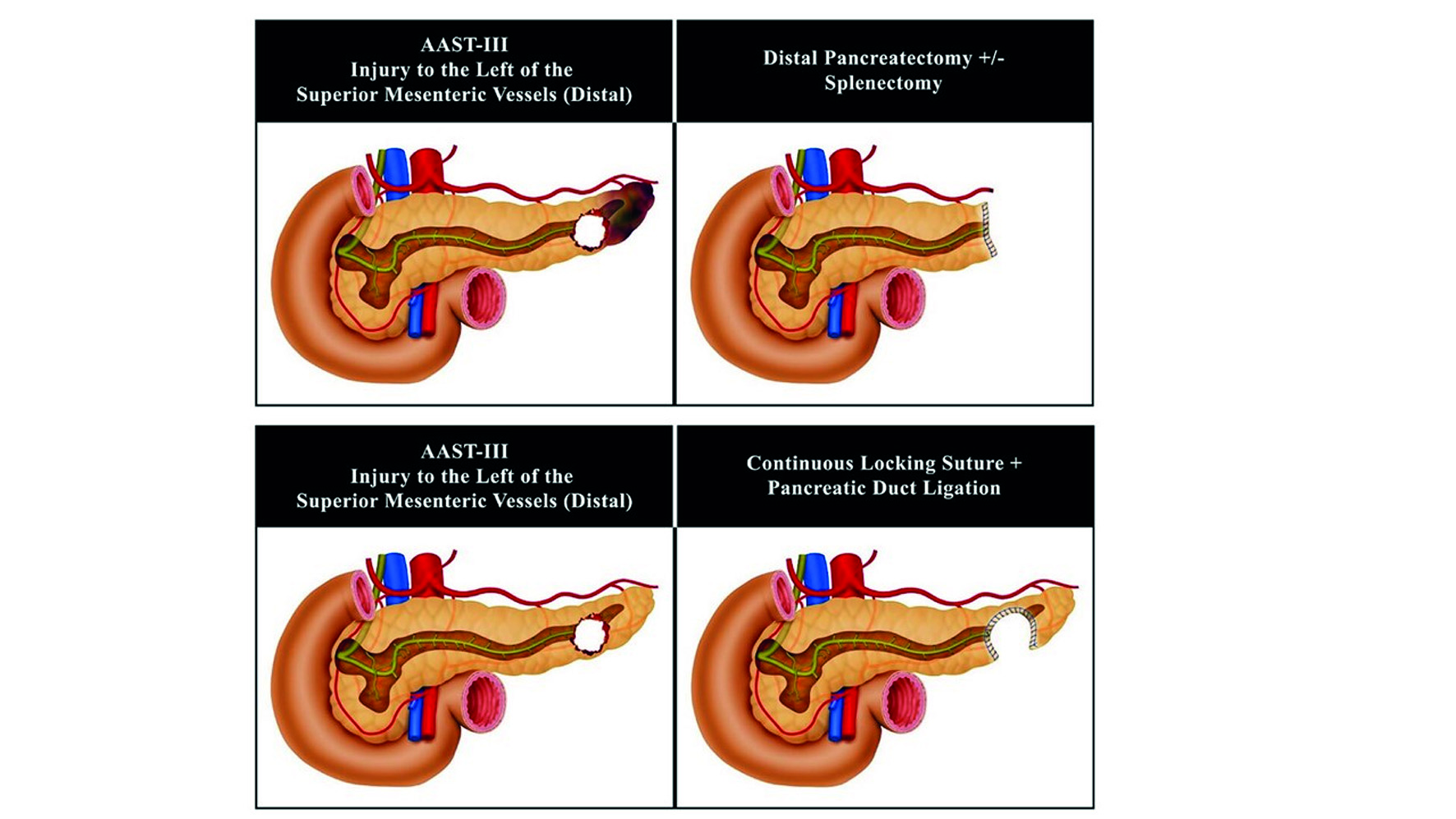

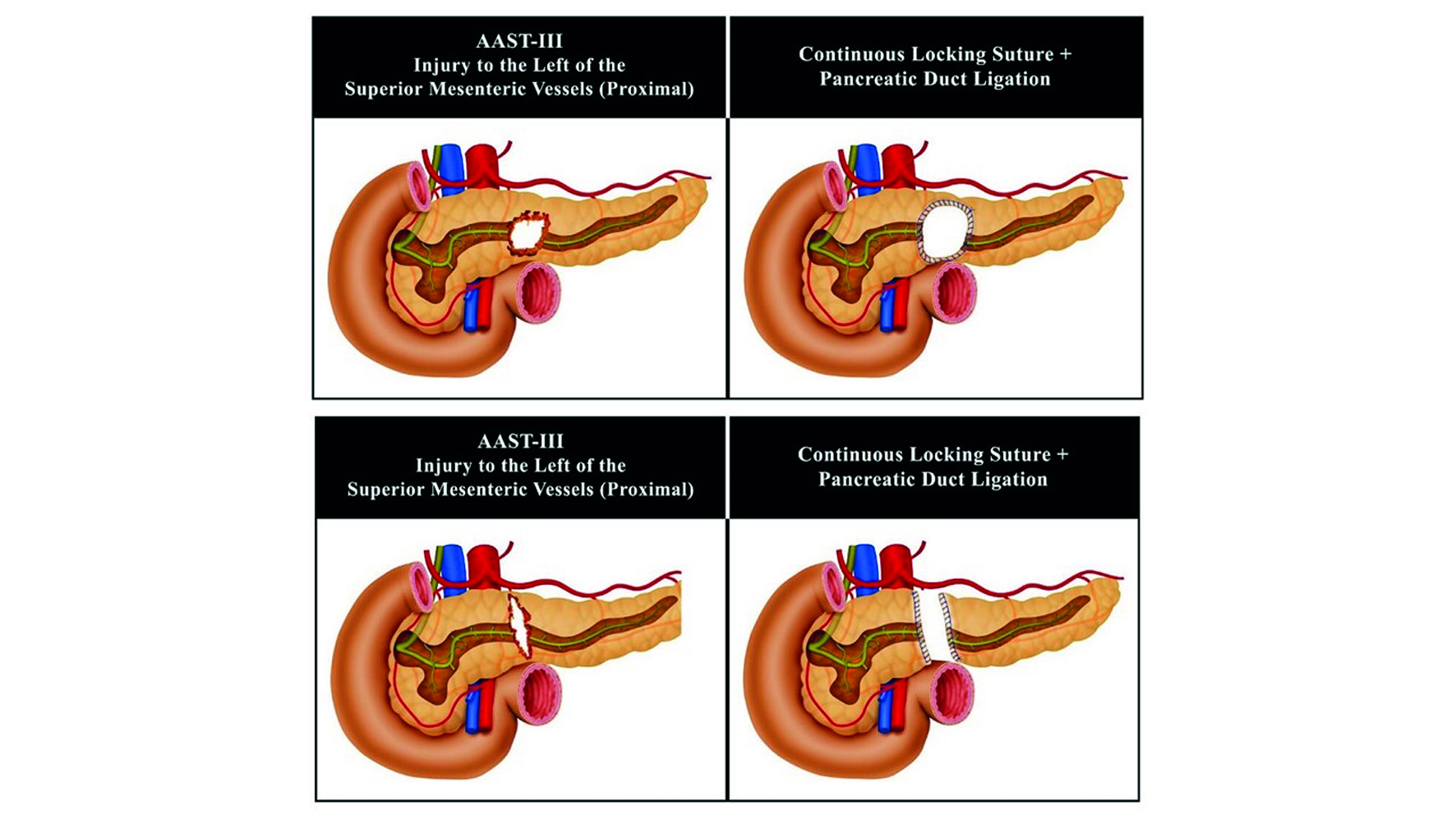

AAST Grade III: hemostasis, distal pancreatectomy +/- splenectomy for injuries of the distal tail of the pancreas with significant tissue destruction, for all other injuries perform a continuous locking non-absorbable monofilament 3-0 suture of the transected borders of the lacerated pancreas, ligate both the proximal and distal ends of the transected pancreatic duct and surgical drainage. It is to note, that in all simple to moderate pancreatic injuries (Grade I-III) may require the implementation of DCS to manage any other significant associated vascular, hollow viscous and/or solid organ injury (Figures 3 and 4)

Figure 3 Surgical Management of Pancreatic Injury AAST-III to the Left of the Superior Mesenteric Vessels (Distal)

Figure 4 Surgical Management of Pancreatic Injury AAST-III to the Left of the Superior Mesenteric Vessels (Proximal)

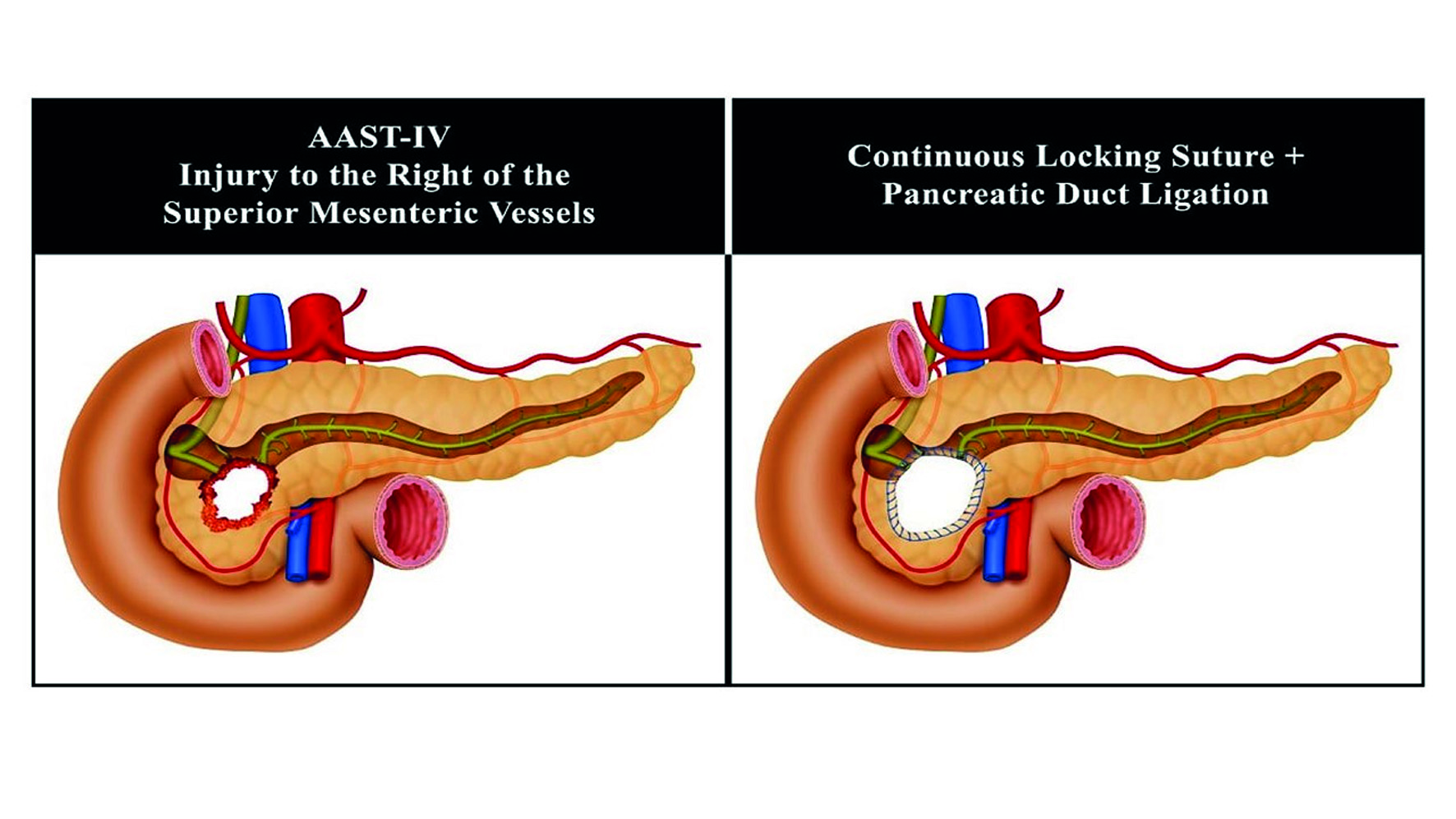

AAST Grade IV: hemostasis by performing a continuous locking non-absorbable monofilament 3-0 suture of the transected borders of the lacerated pancreas, ligate both the proximal and distal ends of the transected pancreatic duct, pack the pancreas and complete your damage control procedure by leaving the abdomen open and placing a negative pressure dressing. In 24-48 hours, after the patient has been appropriately resuscitated and the lethal diamond has been corrected in the intensive care unit (ICU), then the patient is brought back to the OR for unpacking, abdominal washout and surgical drainage (Figure 5)

Figure 5 Surgical Management of Pancreatic Injury AAST-IV to the Right of the Superior Mesenteric Vessels (Proximal)

AAST Grade V: please keep in mind that these patients are critically ill and with an extremely high mortality rate. DCS is a must 18. The main goal is to isolate the pancreatic duodenal complex, performing a continuous locking non-absorbable monofilament 3-0 suture of the transected borders of the lacerated pancreas, ligate both the proximal and distal ends of the transected pancreatic duct, pack the pancreas, proximal control of duodenum by ligature of the first portion of the duodenum with a mechanical stapler, nasogastric and cholecystostomy tube placement to control gastric and biliary output and complete your damage control procedure by leaving the abdomen open, surgical closed drainage and placing a negative pressure dressing. In 24 to 48 hours, after the patient has been appropriately resuscitated and the lethal diamond has been corrected in the ICU, then the patient is brought back to the OR for unpacking, abdominal washout, possible pancreatic duodenectomy (Whipple Procedure) and closed surgical drainage 6,19. The indications for a Whipple Procedure for trauma include: massive injury to the head of the pancreas including the main pancreatic duct, avulsion of the Ampulla of Vater and/or destruction of the second portion of the duodenum 17. If these indications are not present then reassure control of all surgical bleeding and perform closed surgical drainage and definitive abdominal wall closure. If they are present, we recommend that you request assistance from a transplant and/or hepatobiliary surgeon to assist in the reconstruction of a Grade V injury which traditionally requires the re-establishment of bowel continuity, a biliary-enteric and a pancreatic-enteric anastomosis (Figure 6). The later, as the title of this manuscript implies, is in our experience: unnecessary, time consuming and prone to breakdown with significant subsequent complications.

Complications

The reported overall incidence of pancreatic fistula has been between 8 to 33% in patients that have undergone distal pancreatectomies for trauma 11,20-22. That is why we propose the concept of suturing the parenchymal borders of the pancreatic injury to ensure hemostasis and decrease the overall incidence of pancreatic leak. It goes without saying that closed surgical drainage to any mayor injury is a must. Also, the parenchymal wound suturing of the injured pancreas preserves potentially healthy tissue that can, down the line, preserve the organs innate endocrine and exocrine functions. In our own experience, the use of pancreatic parenchymal sutures decreases the incidence of fistula 12. If a pancreatic fistula does arise, closed drainage is the treatment of choice 13. Most pancreatic fistulas are minor and self-limiting with closed drainage. Drains are removed when: the patient has returned to full enteral nutrition, the output of the drain is minimal and the amylase from the drain is equal or less than that of its value in serum.

Conclusion

Most pancreatic injuries are AAST Grades I-III which can be managed with a combination of hemostatic maneuvers, pancreatic packing, parenchymal wound suturing and closed surgical drainage. Distal pancreatectomies +/- splenectomies with the inevitable loss of significant amounts of healthy pancreatic tissue must be avoided whenever possible. General principles of DCS must be applied when necessary followed by definitive surgical management when and only when appropriate physiological stabilization of the patient in the ICU has been achieved 23,24. The general surgical approach to pancreatic injuries to date has been the performance of pancreatic tissue resections for moderate injuries and complex pancreatic-enteric anastomosis in severe cases. It is our experience that viable un-injured pancreatic tissue should be left alone when possible in all types of pancreatic injuries (simple, moderate or complex) accompanied by adequate closed surgical drainage with the aim of preserving primary organ function and decreasing short and long term morbidity.

text in

text in