Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| The aim of this article is to delineate the experience in the surgical management of penetrating duodenal injuries via the creation of a practical and effective algorithm that includes basic principles of damage control surgery which sticks to the philosophy of “Less is Better”. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| Surgical management of all penetrating duodenal trauma should always default when possible to primary repair. When confronted with a complex duodenal injury, hemodynamic instability and/or significant associated injuries then the default should be damage control surgery. Definitive reconstructive surgery should be postponed until the patient has been adequately resuscitated and the diamond of death has been corrected. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| We proposed an easy to follow five-step algorithm for the surgical management of these injuries which sticks to the philosophy of “Less is Better”. |

Introduction

The overall incidence of duodenal injuries in severely injured trauma patients is between 0.2 to 0.6% and the overall prevalence in those suffering from abdominal trauma is 3 to 5% 1,2. Approximately 80% of these cases are secondary to penetrating trauma, commonly associated with vascular and adjacent organ injuries 3-5. These associated injuries create a significant challenge towards the early diagnosis and appropriate management. Therefore, defining the best surgical treatment algorithm remains controversial 6-8. Mild to moderate duodenal trauma is currently manage via primary repair and simple surgical techniques. However, severe injuries have required complex surgical techniques (duodenal diverticulization, pyloric exclusion with or without gastrojejunostomy and pancreatoduodenectomy) without significant favorable outcomes and consequential increase in the rates of mortality 9,10. This article aims to delineate the experience obtained in the surgical management of penetrating duodenal injuries via the creation of a practical and effective algorithm that includes basic principles of damage control surgery (DCS). We have previously reported the concept of “Less is Better,” referring to a minimalistic approach to all duodenal injuries 4. This current manuscript is a sequel in which we reiterate the importance of this concept and propose a new surgical management algorithm towards this effect.

This article is a consensus that synthesizes the experience earned during the past 30 years in trauma critical care management of the severely injured patient from the Trauma and Emergency Surgery Group (CTE) of Cali, Colombia which is made up of experts from the University Hospital del Valle "Evaristo García”, the Universidad del Valle, the University Hospital Fundación Valle del Lili " and Universidad Icesi, the Asociación Colombiana de Cirugia, the Pan-American Trauma Society and the collaboration of international specialists of the United States of America, Europe, Japan, South Africa and Latin America.

Epidemiology

Between 2002 and 2014 a total of 2,163 patients with duodenal trauma were reported by the National Trauma Data Bank, where 80% were men with a median age of 27 (IQR: 20-39) years. Penetrating trauma was the most common mechanism of injury in 64% and the most prevalent injury grade was the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Grade I-II (42%), followed by AAST Grade III (22%), AAST Grade IV (21%) and AAST Grade V (14%) [11]. We reported a retrospective series of 44 patients with penetrating duodenal trauma between 2003 and 2012; 8 patients were excluded because of early operative death, secondary to devastating associated injuries. Ninety-four percent were male with a median age of 26 (IQR: 23-33) years; 93% were by gunshot wounds and 7% by stab wounds. The median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 25 (IQR: 16-25) and 61% presented to the emergency room (ER) in hypovolemic shock. Injury grade distribution was as follows: AAST Grade II 33%, AAST Grade III 44% and AAST Grade IV 22%. All patients had concomitant lesions: 50% colon, 47% small bowel, 44% liver and 39% major vascular. Seven patients required single-stage primary repair, 15 underwent primary repair followed by DCS and 14 required duodenal over-sewing with intestinal discontinuity and subsequent DCS. The overall in-hospital mortality was 11% and duodenal associated mortality was 3% 4.

Initial Approach and Diagnosis

Initial management must be directed towards stabilizing the patient according to ATLS guidelines and following Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) principles 12. Upon arrival, the choice between immediate surgical exploration or further imaging studies is dependent on the hemodynamic status of the patient. If the patient is hemodynamically stable or a transient responder, a computed tomography (CT) should be performed to determine the extent of the duodenal injury and any other significant injuries. The hallmarks of duodenal injury on CT are peri-duodenal emphysema, free fluid in the cavity and/or retroperitoneal hematoma 13. CT with intravenous contrast has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 88% for detecting duodenal lesions 14-16. However, patients with peritoneal signs and/or hemodynamic instability (sustain systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mmHg) should be transferred immediately to the operating room (OR) for the appropriate staging of the injury according to the AAST classification during the initial exploratory laparotomy (Table 1).

Table 1 The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Classification of Duodenum Injuries 17

| Grade | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma | Involving single portion of duodenum |

| Laceration | Partial thickness, no perforation | |

| II | Hematoma | Involving more than one portion |

| Laceration | Disruption <50% of circumference | |

| III | Laceration | Disruption 50%-75% of circumference of D2 Disruption 50%-100% of circumference of D1, D3, D4 |

| IV | Laceration | Disruption >75% of circumference of D2 Involving ampulla or distal common bile duct |

| V | Laceration | Massive disruption of duodenopancreatic complex |

| Vascular | Devascularization of duodenum |

Surgical management

During the initial exploratory laparotomy, the trauma surgeon should initially control all sources of ongoing surgical bleeding followed by control of bowel contamination sources. Only then can he or she direct his or her attention to staging the involved duodenal injury (Table 1), which is usually suspected when one or several of the following are encountered: retroperitoneal hematoma/active bleeding of zone 1, bile spillage, pneumoretroperitoneum and/or projectile trajectory/blast effect. If the patient develops hemodynamic instability during or prior to the procedure with a sustained SBP of 70 mmHg or less, regardless of aggressive DCR, the placement of a Resuscitative Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) should be considered and placed in Zone I as an adjunct 18. Although the management of specific lesions of the duodenum is controversial, ranging from radical approaches such as a pancreatic duodenectomy in cases of AAST Grade V injuries, our general recommendation is to always perform the simplest procedure and to preserve as much tissue as possible. The appropriate staging of a duodenal injury requires complete mobilization of the pancreatic duodenal complex via a Cattel Brash Maneuver with a Kocher extension. After the appropriate staging of the injury, we advocate for definitive surgical repair when possible (AAST Grade I-III) and implementing damage control surgery (DCS) only for those cases of significant injury (AAST Grade IV-V) where surgical reconstruction is unavoidable. We recommend that the classic repair during the initial laparotomy, including duodenal diverticulization, pyloric exclusion, and/or pancreatic-duodenectomy, should be avoided. These procedures are time-consuming, technically difficult and contrary to damage control principles. Also, our solid belief is that during all reconstructions, a nasojejunal tube should be manually placed through the anastomosis and leaving the tip in the distal jejunum for early enteral feeding. We strongly recommend that no further injury should be done to the distal jejunum, which includes the placement of an open jejunostomy tube as is customary in many trauma centers across the world. We believe that this adds potential morbi-mortality in the already compromised severely injured trauma patient. These considerations have been included in the recently published guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) 2019 on duodenal and pancreatic trauma 13. Our surgical management per AAST Grade is as follows:

AAST Grade I: Non-operative management (NOM), nasojejunal tube placement for early enteral feeding, bowel rest and intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation. Attempt oral feeding on hospital day 5.

AAST Grade II: Primary repair with debridement of the lesion if necrotic tissue is suspected or present. The repair is performed using 3-0 or 4-0 PDS absorbable suture as a continuous or interrupted suture line depending on the surgeon’s preference. A nasojejunal tube is placed manually by the surgeon prior to definitive repair of the injury for early enteral feeding, followed by bowel rest and IV fluid resuscitation. Oral feeding is attempted on postoperative day 5.

AAST Grade III:

D1:

D1 injuries that involve between 50 to 100% of the bowel circumference should be repaired when possible by resection plus terminal end to end anastomosis using 3-0 or 4-0 PDS absorbable suture as a continuous or interrupted suture line and/or stapler device depending on the surgeon’s preference and institutional availability of supplies. It is not recommended to perform the suture in two planes. However, if the anastomosis is technically difficult, then the duodenal ends should be left in discontinuity and a nasogastric tube inserted following damage control principles. The patient is then transferred to the ICU for correction of the lethal diamond and in 24 to 48 hours later, the patient should be taken back to the OR for definitive care. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a gastroenteric anastomosis Roux-en-Y (Figure 1).

Figure 1 AAST Grade III D1 Injury with subsequent Reconstruction with a Roux-en-Y. A. D1 Injury involving more than 50% of the bowel circumference B. Damage Control Surgery C. If the anastomosis is technically difficult, then the duodenal ends should be left in discontinuity and a nasogastric tube inserted following damage control principles. D. Duodenal reconstruction via a gastroenteric anastomosis Roux-en-Y

D2:

D2 injuries involving 50 to 75% of the bowel circumference should undergo appropriate staging by making sure that the ampulla or distal common bile duct are not involved. Primary repair with debridement of the lesion should be considered as the first option of surgical approach via a terminal end to end anastomosis using 3-0 or 4-0 PDS absorbable suture as a continuous or interrupted suture line and/or stapler device depending on the surgeon’s preference and institutional availability of supplies. It is not recommended to perform the suture in two planes (Figure 2).

Figure 2 AAST Grade III D2 Injury with subsequent Reconstruction with an End to End Anastomosis. A. D2 Injury involving more than 50% of the bowel circumference B. Primary repair with debridement of the lesion should be considered as the first option of surgical approach via a terminal end to end anastomosis using 3-0 or 4-0 PDS absorbable suture as a continuous or interrupted suture line and/or stapler device depending on the surgeon’s preference and institutional availability of supplies

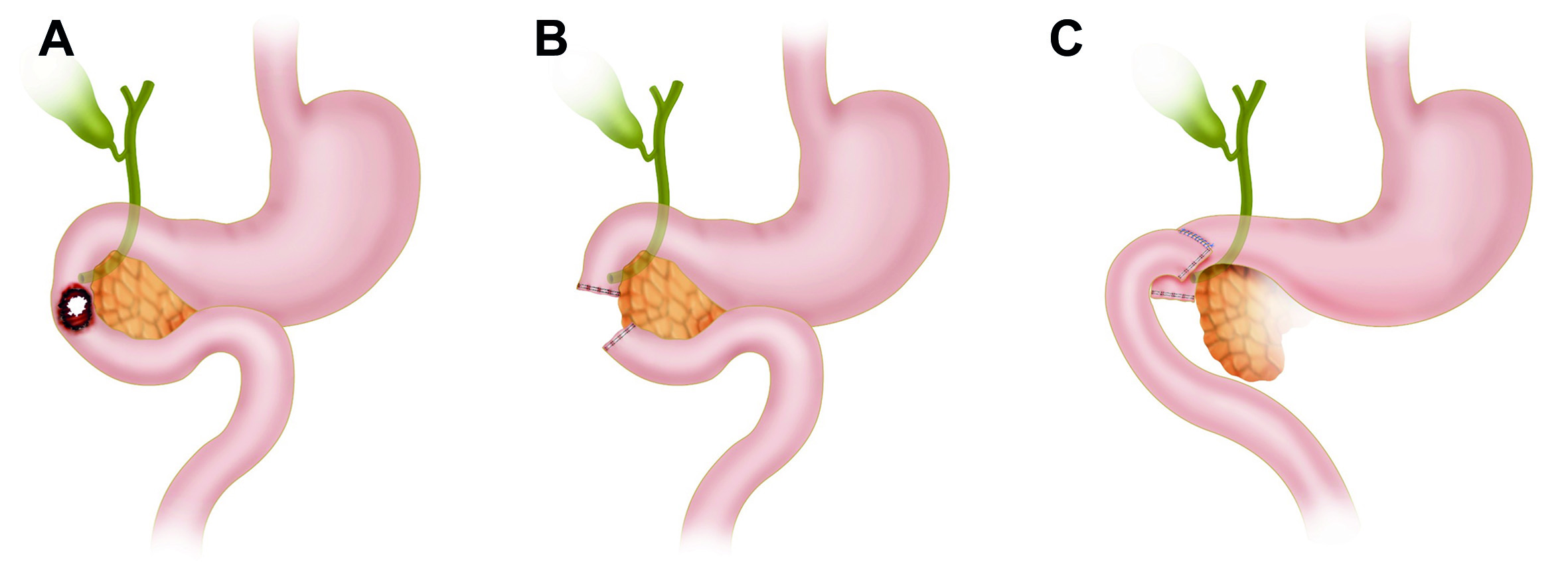

However, if the anastomosis is technically difficult, then the duodenal ends should be left in discontinuity and a nasogastric tube inserted following damage control principles. The patient is then transferred to the ICU for correction of the lethal diamond and in 24 to 48 hours later, the patient should be taken back to the OR for definitive care. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a side to side anastomosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3 AAST Grade III D2 Injury with subsequent Reconstruction with a Side to Side Anastomosis. A. D2 Injury involving more than 50% of the bowel circumference B. The duodenal ends should be left in discontinuity and a nasogastric tube inserted following damage control principles C. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a side to side anastomosis

D3 and D4:

D3 and D4 injuries involving between 50 to 100% of the bowel circumference a Cattel Brash Maneuver with a Kocher extension and a ligament of Treitz release should be done to properly mobilize the bowel and adequately evaluate its viability. When possible, a side to side anastomosis should be performed using 3-0 or 4-0 PDS absorbable suture as a continuous or interrupted suture line and/or stapler device depending on the surgeon’s preference and institutional availability of supplies. However, if the anastomosis is technically difficult, then the duodenal ends should be left in discontinuity and a nasogastric tube inserted following damage control principles. The patient is then transferred to the ICU for correction of the lethal diamond and in 24 to 48 hours later, the patient should be taken back to the OR for definitive care. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a side to side anastomosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4 AAST Grade III D3-D4 Injury with subsequent Reconstruction with a Side to Side Anastomosis. A. D3-D4 Injury involving more than 50% of the bowel circumference B. If the anastomosis is technically difficult, then the duodenal ends should be left in discontinuity and a nasogastric tube inserted following damage control principles C. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a side to side anastomosis

AAST Grade IV: D2 duodenal injuries encompassing more than 75% of the bowel circumference and/or involving the ampulla or distal common bile duct should undergo DCS. This consists of the over-sewing of the duodenal ends, ampulla and/or distal common bile duct. All other significant associated injuries should be addressed, followed by nasogastric and cholecystostomy tube placement, abdominal packing and an open abdomen with a negative pressure dressing. Then the patient should be transferred to the ICU for correction of the lethal diamond, and between 24 to 48 hours later, taken back to the OR for definitive reconstruction. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a choledochal-jejunal, gastro-jejunal anastomosis Roux-en-Y plus cholecystectomy. The pancreas should be left in situ and its borders oversewn with 3-0 non-absorbable monofilament continuous locking suture with adequate peripancreatic closed drainage without stablishing a pancreatic-enteric anastomosis. We recommend the assistance of an experienced hepatobiliary/transplant surgeon due to its technical difficulty (Figure 5).

Figure 5 AAST Grade IV Injury with subsequent Bilio-Enteric Reconstruction. A. D2 duodenal injury encompassing more than 75% of the bowel circumference and/or involving the ampulla or distal common bile duct B. The duodenal ends, ampulla and/or distal common bile duct should be over-sewn. All other significant associated injuries should be addressed followed by nasogastric and cholecystostomy tube placement, abdominal packing and an open abdomen with negative pressure dressing. Duodenal reconstruction should then be performed via a choledochal-jejunal, gastro-jejunal anastomosis Roux-en-Y plus cholecystectomy. The remaining pancreatic tissue is left in-situ followed by over-sewing of any ongoing pancreatic tissue bleeding and a peripancreatic drain placement

AAST Grade V: Duodenal injuries with massive destruction of the duodenal pancreatic complex and/or devascularization of the duodenum require DCS. These patients are associated with extremely high mortality rates and the main objective is to isolate the pancreatoduodenal complex via cross suturing with 3-0 non-absorbable monofilament continuous locking suture of the exposed pancreatic tissue for appropriate hemorrhage control. The duodenal ends, pancreatic duct and distal common bile duct should be over-sewn. All other significant associated injuries should be addressed, followed by nasogastric and cholecystostomy tube placement, abdominal packing and an open abdomen with a negative pressure dressing. Then the patient should be transferred to the ICU for correction of the lethal diamond, and between 24 to 48 hours later taken back to the OR for definitive reconstruction (Figure 6). Indications for a Whipple Procedure in trauma include:

Figure 6 AAST Grade V Injury with subsequent Reconstruction. A. Duodenal injuries with massive destruction of the duodenal pancreatic complex and/or devascularization of the duodenum B. The pancreatoduodenal complex should be isolated via cross suturing with 3-0 non-absorbable monofilament continuous locking suture of the exposed pancreatic tissue for appropriate hemorrhage control. The duodenal ends, pancreatic duct and distal common bile duct should be over-sewn. All other significant associated injuries should be addressed followed by nasogastric and cholecystostomy tube placement, abdominal packing and an open abdomen with negative pressure dressing C. The reconstruction should consist of a choledochal-jejunal, gastro-jejunal anastomosis Roux-en-Y plus cholecystectomy. The remaining pancreatic tissue is left in-situ followed by over-sewing of any ongoing pancreatic tissue bleeding via a 3-0 non-absorbable monofilament continuous locking suture

⭘ Massive injury to the head of the pancreas with pancreatic duct involvement

⭘ Avulsion of the ampulla of Vater

⭘ Destruction of the second portion of the duodenum

If present, then the assistance of an experienced hepatobiliary/transplant surgeon should be requested and the Whipple procedure performed. Then the patient should be transferred back to the ICU to continue the patient’s recovery.

If the indications for a Whipple Procedure are not met, then all surgical hemorrhage should be controlled and a Cattel Brash Maneuver with a Kocher extension and a ligament of Treitz release should be done in order to properly mobilize the bowel and adequately evaluate its viability. The reconstruction should consist of a choledochal-jejunal, gastro-jejunal anastomosis Roux-en-Y plus cholecystectomy. The pancreas should be left in situ and its borders oversewn with 3-0 non-absorbable monofilament continuous locking suture with adequate peripancreatic closed drainage without stablishing a pancreatic-enteric anastomosis (Figure 6). We recommend the assistance of an experienced hepatobiliary/transplant surgeon due to its technical difficulty. Then the patient should be transferred back to the ICU to continue the patient’s recovery.

We have developed an easy to follow five-step management algorithm that clearly illustrates the surgical care of patients with penetrating duodenal trauma according to their AAST Grade (Figure 7).

Complications

The main complication of these injuries are duodenal leaks that evolve into fistulas because it sees approximately 5 liters of fluid per day (gastric acid, bile, pancreatic juice and saliva). The Memphis surgery group in 2016, described their 19 years of experience in the management of these injuries and compared patients who developed a duodenal leak to those who did not. They found no significant difference in readmission rates, operative time, mortality, or other associated complications. However, longer hospital stays and abdominal abscess formation were more prevalent in the patients who developed duodenal fistulas 4,10.

Duodenal leaks can be managed by percutaneous drain placement, exploratory laparotomy with closed external drainage or a retroperitoneal laparostomy with open external drainage (Lumbotomy) 19. The latter, is an alternative approach to the classic anterior exploratory laparotomy or the current percutaneous management by interventional radiology because of its technical ease and the allowance of re-exploration, drainage and debridement of necrotic tissue without the risk of intraperitoneal cross-contamination. This procedure requires a 15cm right transverse subcostal flank incision that extends from the anterior axillary line to the posterior axillary line. After the incision, all flank muscles are split and blunt dissection is made of the retroperitoneum just above the renal fossa until the duodenum is exposed. The wound is packed for 24 hours followed by unpacking and placement of a colostomy bag for fluid drainage collection or a negative pressure dressing (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Retroperitoneal Laparostomy (Lumbotomy). This procedure requires a 15 cm right transverse subcostal flank incision that extends from the anterior axillary line to the posterior axillary line. Subsequent to the incision, all flank muscles are split and blunt dissection is made of the retroperitoneum just above the renal fossa until the duodenum is exposed. The wound is packed for 24 hours followed by unpacking and placement of a colostomy bag or a negative pressure dressing

The benefit of this procedure is that it takes into account the natural tendency of a duodenal fistula to flow posteriorly by gravity effect rather than the traditional anterior approach with active drain suction. Also, it does not require expensive hospital infrastructure (Angiosuite/CT scanner/hybrid room) which is true for percutaneous management 20-22. For all these reasons, retroperitoneal laparostomy (Lumbotomy) should be included in your armamentarium to manage these complications 4.

Discussion

Between 2002 and 2014, a total of 2163 duodenal trauma patients were reported by the National Trauma Data Bank. The median ISS was 18 (IQR: 13-26) and the in-hospital mortality was 12%. Of the total, 55% had isolated duodenal injuries with a mortality of 8%. The factors associated with increased mortality were: hypotension upon admission, neurologic involvement (Glasgow Coma Scale < 9), penetrating mechanism and an ISS > 15 11. In a subsequent retrospective sub-analysis, mortality was up to 30% in patients with AAST Grade IV injuries and 38% in AAST Grade V 23. The most common surgical intervention was primary repair in 72%, followed by pyloric exclusion in 11%, duodenojejunostomy in 11% and pancreatoduodenectomy in 2% 11. Similarly, the Panamerican Trauma Society conducted a retrospective multicenter study from 2007 to 2016, and found a total of 372 patients with duodenal injuries. The median ISS was 18 (IQR: 16-25) and the injuries were classified as AAST Grade I-II in 24%, Grade III 62%, Grade IV in 11% and Grade V in 3%. They also found that primary repair was feasible in most cases (80%) and more extended surgeries such as primary repair with retrograde decompressive duodenostomy in 10%, pyloric exclusion with gastrojejunostomy in 4%, pyloric exclusion without gastrojejunostomy in 4%, resection with primary anastomosis in 1% and pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1%. The duodenal leak rate was significantly lower in patients who had primary repair regardless of the AAST grade of injury 24.

In contrast, we found in our series of 36 patients with penetrating duodenal trauma that 19% underwent definitive primary repair and the other 81% required damage control laparotomy. Of the patients that required DCS, more than half (52%) were eventually managed by delayed primary repair. The most common complication was the development of a duodenal leak in 33%. These were managed by traditional anterior drainage in 75% and posterior drainage by retroperitoneal laparostomy (Lumbotomy) in 25%. The duodenal fistula closed in 58% of managed cases 4. We learned that the overall concept of "Less is Better" is true to its nature and simple repair techniques should always be the default and complicated reconstructive surgeries should be avoided at all costs. This is why we have devised a simple to follow five-step surgical management algorithm that applies DCS concept for complex AAST Grade injuries. We believe that the subsequent definitive reconstruction of these complex injuries require the assistance of an experienced hepatobiliary/transplant surgeon when available. If this type of assistance is not readily available, then the patient should be transferred as soon as possible to a facility that has these resources.

Conclusion

Surgical management of all penetrating duodenal trauma should always default when possible to primary repair. When confronted with a complex duodenal injury, hemodynamic instability and/or significant associated injuries then the default should be DCS. Definitive reconstructive surgery should be postponed until the patient has been adequately resuscitated and the diamond of death has been corrected. To this end, we proposed an easy-to-follow the five-step algorithm for the surgical management of these injuries, which sticks to the philosophy of “Less is Better”.

text in

text in