INTRODUCTION

There is great evidence from research to support the positive impacts of entrepreneurship on economic growth (Medina et al., 2019; Navarro et al., 2019; Khajeheian, 2017; Dastourian et al., 2017). The value of entrepreneurship as a powerful force that shapes economies lies in its ability to overcome unemployment which is a major problem facing countries in both the developed and emerging economies (Ndofirepi, 2016; Ahmad & Xavier, 2012). According to the evidence provided by Sternberg and Wennekers, (2005) higher entrepreneurial activities and innovation are both crucial to economic growth. Quillas et al. (2020) documented a positive relationship between the quality of formal institutions and the level of human development in the country.

In Saudi Arabia, entrepreneurship is developing to become an important determinant of economic growth as outlined in the country’s vision 2030. The KSA 2030 vision plans to minimize the country’s overdependence on oil, diversify the economy and improve the public sector especially the health, education, infrastructure, recreation and tourism sectors. The goals of the 2030 vision plan are to reinforce economic and investment activities in the country, improve the oil industry trade with other countries and increase the government spending on military, manufacturing and ammunition. The focus of the 2030 vision plan is also to increase the entrepreneurial activities in the country which would contribute significantly to economic growth.

Given the importance of entrepreneurship in building national economies, Gelard and Saleh (2011) recommend that governments and schools should prioritize the entrepreneurial intentions of their students. Even though there is a large amount of research on entrepreneurship education, evidence to support its effects is scarce and the effects are poorly understood. Most of the available research has not been conducted in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, as a field of study, it is clear that more research is needed and should be conducted on the effects of entrepreneurship education. Supporting students’ entrepreneurial intentions would help achieve KSA vision 2030 plan. The KSA vision 2030 plan awareness among business administration students at Northern Border University are not well known. As such, this study seeks to report the degree to which BA students at the Northern Border university are aware of the KSA 2030 plan and also to examine the entrepreneurial intention of these students in relation to the plan.

The significance of this study is that it will allow policy makers in the ministry of education and other parties at the Northern Border University to understand and translate the outcomes from the study into real life situations. Activities within the institutions would be transformed positively in support of entrepreneurial intentions thus helping the country achieve 2030 vision. Not only would the information in the study help in solving real work problems or challenges but would also promote availability of opportunities in the KSA environment. These opportunities may include;

Improving the contribution to Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) to GDP

Reducing the gap between outputs from the higher education sector and the needs of the job market

Developing appropriate skills and talent among youths, strengthening their futures and increasing their chances of creating employment and contributing to national development.

Through these opportunities, supporting entrepreneurial intentions among students would be playing a wider role in supporting the KSA 2030 vision. The findings from this study would also interest researchers and the academic community; the research would shed more light into research attempts to examine issues of entrepreneurship in KSA universities. The findings from the research would also provide information that is customized to the context of KSA thereby contributing significantly to the pool of information and knowledge on entrepreneurial intentions of students and its future role in supporting economic growth of the country and achievement of KSA 2030 vision.

This study is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature, section 3 highlights the research methodology, section 4 addresses the results and discussions, and the final section illustrates the conclusion.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Saudi Arabian Context

Saudi Arabia or the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is the largest country in the Arabian Peninsula, bordered to the north by Iraq, Jordan and Kuwait, and to the east by the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and the Persian Gulf, Oman to the southeast, and Yemen to the south. Saudi Arabia is the Muslims’ religious destination. There are religious sites sacred to Muslims, such as the Holy Mosque and the Kaaba, the honourable Qibla of Muslims, in Makkah and the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. Saudi Arabia’s economy ranks among the most powerful economies in the world as a member of the G20. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia possesses 18.1% of the proven reserves of oil in the world, ranking second in the world, and it has the fifth largest proven reserves of natural gas, and it is a member of OPEC. It comes in third place after Russia and the United States in terms of natural resources, which are estimated to be worth about 35 trillion US dollars, seventh among the G20 countries and 26th globally in the global competitiveness standard, according to the Global Competitiveness Yearbook, 2019 report, issued by the International Institute for Administrative Development, which measures the competitiveness of 140 countries worldwide, depending on the state’s ability to benefit from its available resources.

With its economy based on being the largest oil exporter, Saudi Arabia, since 2016, has sought to carry out economic reforms that reduce dependence on oil as a major economic activity, and has developed strategies to diversify non-oil income sources within the so-called Saudi Vision 2030. These reforms have raised the expected economic growth rate from 1.8% in 2019 to 2.1%. 2020. The reforms implemented by the Kingdom, represented in the establishment of the one-stop- shop system for company registration, the introduction of a secured transactions law, a bankruptcy law, improved protection for minority investors, and measures to include more women in the workforce, contributed to its advancement of 30 ranks for the year 2019 in the Doing Business 2020 report issued by the World Bank. It has become the most advanced and reformed country among 190 countries around the world, achieving first place in the world in business environment reforms among the countries covered by the report in the Ease of Doing Business Index.

Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia

As part of its revised approach to economic diversification and to achieving Saudi Vision 2030 aims, the government of Saudi Arabia has implemented several policies and adopted a variety of supporting mechanisms and policies instituted for entrepreneurs as well as formed many entities, such as the General Authority for Small to Medium Enterprises Authority (SMEs’ Authority), Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority (SAGIA) and The Human Resource Development Fund (HRDF). In addition, there are 28 different chambers of commerce, under the umbrella of the Council of Chamber of Commerce and Industry, which support entrepreneurs in various capacities. These services include staging counselling, funding, education and training programs with local entrepreneurs (Ashri, 2013; Shirzai, 2017).

Saudi Arabia is ranked as the 29th most competitive economy among the 138 economies in 2016. Its national economy ranks relatively high in all pillars, but scores low on innovation and business sophistication (Shirzai, 2017). As part of Saudi Vision 2030 to provide high-quality education to its citizens, entrepreneurship education in particular and increased emphasis on embedding entrepreneurship in higher education institutions, has been carried out by the government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, through Saudi universities, has established a number of entrepreneurship centers nationwide for providing consultations, feasibility studies, and follow-up projects in the areas of entrepreneurship, and facilitating procedures for obtaining loans and financing for project owners and financing necessary to start projects.

KSA 2030 Vision and Education

Undoubtedly, education plays an integral role in the economic growth of a country. Primarily, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has identified education to be one of the key factors in achieving its Vision 2030. As such, the Kingdom aims to eliminate the existing correlational gap between completing higher education and meeting the job requirements in the market. Therefore, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will engage students in career choice seminars to assist them to make wise career decisions and explore educational pathways that will maximize their potentials. Notably, the Kingdom hopes that this will enable it to achieve its target of having at least five local universities among the top 200 internationally. Thus, the Kingdom will place a high priority in assisting its scholars to attain higher performance results as per the global education indicators.

Correspondingly, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will formulate and implement a modern education program which will principally focus on values that enhance the learners’ character development, skills, and numerical abilities. Moreover, besides offering an array of courses to students, the Kingdom will track the students’ annual performances to enable it to evaluate the system’s improvement trends. Further, the Saudi Arabian Kingdom will involve the private sector to ensure that its higher education programs conform to the needs of the current market employment requirements.

Markedly important, the Kingdom will work on developing job specifications on all the courses offered in its various vocational and higher learning institutions. To facilitate this, the Kingdom will largely be engaged in strategic partnerships with private organizations, apprenticeship providers, and industry skill councils. Ultimately, the Saudi Arabian Kingdom will establish a contemporary database tracking system, which will be used to trace the students’ performance from early childhood to the moment they will complete their higher learning education. The data will be essential in enhancing the Kingdom’s agenda to improve education and economic growth as it will enable it to effectively plan, monitor, and assess the performance progress of students.

Northern Border University

Northern Border University, a Saudi university, was founded by the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz during his historic visit to the Northern Border region in 1428 AH - 2007 AD. The College of Science in Arar, which was afiliated with King Abdul Aziz University, was included and then the College of Teachers (Education and Arts now) and several other colleges in the governorates of Rafha, Turaif and Al-Uweqila, to form together the Northern Border University. After the university was announced, a number of colleges were established with specific specializations such as: medicine, engineering, computer technologies, pharmacy, nursing, administration, medical sciences and community sciences. The university administration headquarters is located in the city of Arar, the administrative centre for the northern border region, and the university has three branches in the governorates of Rafha, Turaif and Al-Uweqila.

College of Business Administration

The College of Business Administration at the University of Northern Borders was established by virtue of the decision of the Higher Education Council at its fortyninth session on 7/9/1429 AH - where the approval of the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, Prime Minister and Chairman of the Higher Education Council, was issued to establish it to be within the colleges of the Northern Borders University.

North Entrepreneurship Centre

The Center provides consultations, feasibility studies, project follow-up in the areas of entrepreneurship, and facilitates procedures for project owners and innovations to obtain loans and financing needed to start projects. The importance of the Center for North Pioneers, is acquiring a topic of great importance, through its earnest endeavour to direct the university towards a societal partnership and a shift towards a knowledge economy by strengthening the relationship and communication between the society’s institutions by mixing scientific frameworks with practical experiences. In addition, it aims to ensure the quality of the educational process, and achieving learning goals. The goal of this applied practice is to produce productive students who have gained suficient knowledge, skills, creativity, and successes with productive project management.

The Vision:

Leadership and excellence in creating the appropriate environment conducive to innovation and practicing entrepreneurship in the northern border region.

The Mission:

Raising the University of Northern Borders to the ranks of regional universities, both regionally and globally, in the areas of leadership and innovation, by supporting entrepreneurial ideas and developing the spirit of innovation, with the aim of transforming ideas into value-added products.

Objectives:

Support the transformation of the Northern Border University into a creative, innovative university.

Creating a culture of entrepreneurship among the university’s employees.

Qualifying students and providing them with the knowledge competencies and skills to put forth innovative ideas and new creations that invest in launching their entrepreneurial projects.

Provide distinctive educational and training programs to develop the capabilities of community members and enable them to establish and manage entrepreneurial projects in cooperation with the relevant authorities.

Providing organizational and technical support, economic consultations and feasibility studies for owners of innovations and small projects.

Work with government and private funding agencies to support promising projects and monitor their growth and development in the local market.

Contribute to the transfer of promising innovations from the university to various commercial and economic sectors.

Motivating creators and investing in their innovations and talents in order to serve the community.

Marketing productive projects, support and property rights for distinctive innovations.

Providing job opportunities for innovators and creators.

Building strong strategic partnerships with entities related to entrepreneurship and small projects in order to support all forms of innovation.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Research Design

The choice of an appropriate research design and methodology is crucial to ensuring that research objectives and questions are addressed appropriately. Based on the purpose of this research, a quantitative research approach would be the most appropriate. For this research, a quantitative research approach was preferred since the study would collect data using survey research. The following research questions were identified for this study, and would be examined using a questionnaire survey method;

What is the level of the KSA 2030 Vision awareness among College of Business Administration students at Northern Border University?

To what extent does the entrepreneurship intention associate with the awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision among students in the College of Business Administration at Northern Border University?

The methodological approach preferred in this study was adopted from previous studies that can fit in the Saudi environment (Aneizi, 2009; Luthje & Franke, 2003; Ajzen, 1992, 2002; Nabi & Holden, 2008; Kolvereid 1996; Scholten, et al., 2004; Fayolle, et al., 2006; Shapero & Sokole, 1982; Davidsson, 1995; Kolvereid, 1996). The questions included in the questionnaire are designed to investigate the following:

The degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness among students in College of Business Administration at Northern Border University. An exploratory analysis is done to report the degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness among the students. The degree is then ranked as low, medium or high awareness.

The association of entrepreneurial intention with the KSA 2030 Vision awareness among students in College of Business Administration at Northern Border University. The degree of entrepreneurial intention is, empirically, tested with the level of KSA 2030 Vision awareness in order to identify the extent to which the entrepreneurial intention is associated with the KSA 2030 Vision awareness. The dependent variable for the model (1) is the KSA 2030 Vision awareness and the independent variable is the entrepreneurial intention.

Hypothesis Development

Entrepreneurial intention and KSA 2030 Vision awareness

A significant amount of literature has been published to support the positive effects of entrepreneurship on economic growth (Navarro, et al., 2009; Acs & Szerb, 2007; Audretsch & Thurik, 2001; Marchesnay, 2011; Kasseeah. 2016; Ahmad & Xavier, 2012). Most of these studies acknowledge the fact that entrepreneurship can be a powerful tool for improving the economy especially because it significantly reduces the rate of unemployment which is a major problem facing countries across the world including both the developed and developing (Ndofirepi, 2016; Ahmad & Xavier, 2012).

Higher levels of entrepreneurship activities coupled with effective innovations are considered to be major ingredients to economic growth (Sternberg and Wennekers, 2005). Through entrepreneurial activities and entrepreneurship, it has become easier for the progress, quality and future expectations of economies or nations to be estimated. Through entrepreneurship activities or actions SMEs promote economic growth and help nations develop a strong economic base (Goedhuys & Sleuwaegen, 2000; Ruiz et al., 2016). Entrepreneurs are expected to show greater creativity and innovation that may be used for creating change in the society, especially from a macroeconomic perspective (Wennekers et al., 2002; Wyness et al., 2015; Shamsudin et al., 2017). In Saudi Arabia, the government has developed major developmental policies that support entrepreneurship. These efforts are evidenced by the many supporting mechanisms and policies that are currently ongoing and are implemented by the government.

After recognizing the value of supporting and developing entrepreneurship, Saudi Arabia has made significant progress in supporting upcoming entrepreneurs. Being the largest economy in the Middle East, implementation of entrepreneurship policies is a huge step towards economic success in the region. The country recognized the fact that supporting entrepreneurship was the among the most appropriate methods for achieving its vision 2030 plan. Part of the vision 2030 is to minimize the country’s overdependence on oil, diversify the economy and develop the public sector. Since one of the major focus areas of the vision 2030 is reduction of unemployment, promoting entrepreneurship is one of the most effective ways the government can use to reduce the unemployment rate. Saudi universities and especially business schools and entrepreneurship centers have been supported fully by the government in efforts to increase entrepreneurship levels among the young people in the country. These educational institutions have a wider role to play in promoting entrepreneurial activities and education. Thus, the following hypothesis is developed to be tested by this study: H 1 : Entrepreneurial intention is associated with the KSA 2030 Vision awareness.

Questionnaire Design

It was noted earlier that this study focused on quantitative methodology that is based on a questionnaire survey approach. The questionnaire was adopted from other studies done previously (Aneizi, 2009; Luthje & Franke, 2003; Ajzen, 1992, 2002; Nabi & Holden, 2008; Kolvereid 1996; Scholten et al., 2004; Fayolle et al., 2006; Shapero & Sokole, 1982; Davidsson, 1995; Kolvereid, 1996). To facilitate data collection, the survey was developed in the Arabic language and distributed to the sample chosen for the study. The rationale for choosing the survey instrument was to allow easier study of the students and to increase the response rates.

The study questionnaire was grouped into two sections; A and B. In section A of the questionnaire, the researchers focused on collecting demographic information from the respondents including gender, age, specialization and level of study. However, the section B of the questionnaire focused on collecting data related to the research questions and was further subdivided into two parts. Part 1(question 1) is used to measure the student intention to become entrepreneurs after school while part 2 (question 2) measures the level of student’s awareness and knowledge with regards to the KSA 2030 Vision.

Instrument of Measurement

Section B, part 1: Measurement of entrepreneurial intention

A major concern for the study is entrepreneurial intention. This variable is a 1-item variable measured by a four-point Likert scale. The variable explored the extent to which the participants have the intention to become entrepreneurs in the future. The four-point Likert scales varies from 1 (very improbable), indicating to the lowest entrepreneurial intention, to 4 (very probable), indicating to the highest entrepreneurial intention. The scales use for collecting the data can be grouped into four groups: “1” (very improbable) indicates to the very low entrepreneurial intention, “2” (quite improbable) indicates a low entrepreneurial intention, “3” (quite probable) indicates a high entrepreneurial intention, and “4” (very probable) indicates a very high entrepreneurial intention. In addition, an item was developed to measure whether the respondents agreed to start an entrepreneurial project in the future. The item was asked in the form of the following statement, “I plan to become self- employed in the foreseeable future after graduation.” If a significant level of the given item “entrepreneurship” is at 0.05 or low, it is considered a significant relationship, otherwise it is not.

Section B, part 2: Measurement of the KSA 2030 Vision awareness

The variable “KSA 2030 Vision awareness” consists of 12 items to measure the extent to which the students are aware of the KSA 2030 Vision. In specific, the extent to which opening more entrepreneurial projects would contribute to achieving the KSA 2030 Vision. A score index is used to measure the level of awareness towards the specific-country issues that would be influenced by the entrepreneurial projects. The score index is a composite measure that sums the value of the 12 dichotomous items of the KSA 2030 Vision awareness to create a KSA 2030 Vision awareness that takes a score bounding by 0-1, revealing that a higher score is an indicator of a higher KSA 2030 Vision awareness. The 12 items that are included in this measurement are: decreasing the level of unemployment and creating more jobs, increasing the contribution of the national income, increasing the participation of women in businesses, increasing the governmental non-oil revenues, increasing the individual’s income growth, achieving economic growth, achieving social benefits, attaining political stability, developing male and female youth’s talent innovation and productive capabilities, enhancing the country’s Global Competitiveness Index, increasing foreign investment, and increasing the university’s rank. These 12 binary items are ranging from 0-12. If a significant level of the given items and for the overall category entrepreneurial education and support is at 0.05 or lower, it is considered a significant relationship, otherwise it is not.

Models Specifications and Analyses

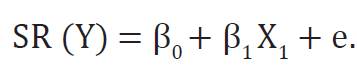

This study applies two Simple Regression (SR) models. Nominal and continuous values were assigned to measure the value of the independent variables. In particular, Model 1 can be expressed as follows:

Where the dependent variable is:

SR (Y) = KSA 2030 Vision awareness (significance at level 0.05).

Where the independent variables are:

X1 = entrepreneurial intention

E = Error term.

The analyses of data were completed using the SPSS version 20 for Windows. A descriptive statistical analysis using frequencies and percentages were used to describe the demographic variables. Research questions were addressed using descriptive statistical analysis and simple regressions.

Data Collection

With regards to sampling, simple random sampling is preferred. The rationale for choosing simple random sampling is based on the fact that it allows the most suitable sample to be used for collecting the data for the study. The study sampling approach is ideal because it allows the researchers to collect data from a sample that is a good representation of the wider population under study. The electronic survey is developed and designed in Google forms, which are easy to distribute to the respondents, and can reach out to a large number of people. The student and faculty members are allowed to access the link for the electronic survey so that it can be distributed to as many students as possible. The distribution technique resulted in sample of 1,400 respondents. These sample was regarded as the most appropriate for providing data about the constructs being examined in the study. The target population for the sample include students specializing in accounting, finance, marketing, human resources and law. The sample was collected from students taking different courses at the College of Business Administration at Northern Border University, for the academic year 2019-2020. A response rate of 23% was recorded meaning 326 questionnaires were completed and returned (Table 3.1)

Table 3.1 Sample selection

| Male section | Female section | Totals | |

| Department of Law | 271 | 170 | 441 |

| Department of Accounting | 85 | 164 | 249 |

| Department of Human Resource Management | 206 | 299 | 505 |

| Department of Finance | 39 | 102 | 141 |

| Department of Marketing | 26 | 38 | 64 |

| Totals | 627 | 773 | 1400 |

| Returned respondents | 151 | 175 | 326 |

| Invalid surveys | (24) | (36) | (60) |

| Final sample | 127 | 139 | 266 |

Approximately 6% of the surveys were reported as uncompleted surveys by the respondents. So that these survey were distracted from the analysis process.

Results and Discussions Profile of Respondents

A total of 266 questionnaires were gathered from the survey. As shown in Table 4.1, the majority of the respondents (52.3%) were male, and (47.7%) were female.

Table 4.1 Profile of respondents

| Demographic information | Frequency (n = 266) | Percent % | ||

| Panel A: Nominal variables | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 127 | 47.7 | ||

| Female | 139 | 52.3 | ||

| Specialization | ||||

| Accounting | 105 | 39.5 | ||

| Law | 121 | 45.5 | ||

| Human resources | 27 | 10.2 | ||

| Finance | 12 | 4.5 | ||

| Marketing | 1 | 0.4 | ||

| Study level | ||||

| First level | 10 | 3.8 | ||

| Second level | 7 | 2.6 | ||

| Third level | 43 | 16.2 | ||

| Fourth level | 206 | 77.4 | ||

| Panel B: Continuous variable | ||||

| Mean | Minimum | Maximum | St. Devation | |

| Age | 22 | 19 | 39 |

In terms of the age, the average of the students is 22 with a minimum of 19 and a maximum of 39. With regard to specialization, the largest group (45.5%) was law students, (39.5%) accounting students, (10.2%) human resources students, (4.5%) students, and (0.4%) marketing students. Regarding the level of study, the majority of the students (77.4%) was the fourth level, (16.2%) the third level, (3.8%) the first level, and (2.6%) the second level.

Entrepreneurial Intention

The study also asked the participants about their future plans. Specifically, the participants were asked whether they planned to become self-employed in the future after graduation. A large number of the respondents (50%) indicated that they will be probable while 46.6% noted that they are very probably likely to become entrepreneurs after graduation. However, only 3% noted “improbable” while 0.4% noted that they were very improbable and were not thinking of becoming entrepreneurs in the future.

Table 4.2 Entrepreneurial intention (I plan to become self-employed in the foreseeable future after graduation)

| Scale | Frequency (n = 266) | Percent % |

| Very probable | 124 | 46.6 |

| Probable | 133 | 50 |

| Improbable | 8 | 3 |

| Very improbable | 1 | 0.4 |

| Total | 266 | 100 |

As illustrated in Table 4.2, a majority of the respondents had high levels of intentions to become entrepreneurs in the future after graduation. These findings provide a positive cue towards the value of entrepreneurship and its importance in supporting economic growth. The high number of people hoping to enter into entrepreneurship is a positive signal for economic growth (Sternberg & Wennekers, 2005; Navarro et al., 2009; Acs & Szerb, 2007; Audretsch & Thurik, 2001; Marchesnay, 2011; Kasseeah. 2016; Ahmad & Xavier, 2012). In addition to the importance of entrepreneurship in supporting economic growth, it has also been linked to increasing employment opportunities for people (Ndofirepi, 2016; Ahmad & Xavier, 2012).

KSA 2030 Vision Awareness

Respondents were asked to rate different items of KSA Vision awareness in order to document the degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness among students in the College of Business Administration at Norther Border University as depicted in Table 4.3:

Table 4.3 KSA 2030 Vision awareness

| Statements | Frequency | percent % | |

| 1 | decreasing the level of unemployment and creating more jobs | 124 | 47 |

| 2 | increasing the contribution of the national income | 60 | 25 |

| 3 | increasing the participation of women in the businesses | 88 | 33 |

| 4 | increasing the governmental non-oil revenues | 36 | 14 |

| 5 | increasing the individual’s income growth | 107 | 40 |

| 6 | achieving economic growth | 62 | 23 |

| 7 | achieving social benefits | 90 | 34 |

| 8 | attaining political stability | 32 | 12 |

| 9 | developing male and female youth’s talent innovation and productive capabilities | 60 | 25 |

| 10 | enhancing the country’s Global Competitiveness Index | 29 | 11 |

| 11 | increasing the foreign investment | 16 | 6 |

| 12 | increasing the university rank | 48 | 18 |

| Overall | 752 | 24 |

As illustrated by Table 4.3 that the highest degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness was given to the item “decreasing the level of unemployment and creating more jobs” (47%) and the lowest degree was given to the item “increasing the foreign investment” (6%). The overall score for the 12 items was 24%, indicating a low degree of awareness among the College of Business Administration’s students towards the impact of the entrepreneurial project on the achievement of the KSA 2030 Vision. This gives an alarming warning to the policy makers at the university and the college levels to consider spreading the awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision and how opening new ventures can contribute to the attaining of the vision.

Hypotheses Testing

Entrepreneurial Intention and KSA 2030 Vision

The objective of this study is to examine the degree of entrepreneurial intention with the KSA 2030 Vision awareness to identify the extent to which the entrepreneurial intention is associated with the KSA 2030 Vision awareness. The dependent variable is the KSA 2030 Vision awareness and the independent variable is the entrepreneurship intention. The dependent variable “KSA 2030 Vision awareness” consists of 12 items to measure the extent to which the students are aware of the KSA 2030 Vision. A score index is used to measure the level of awareness towards the specific-country issues that would be influenced by the entrepreneurial projects. The score index is a composite measure that sums the value of the 12 dichotomous items of the KSA 2030

Vision awareness to create a KSA 2030 Vision awareness that takes a score bounding by 0-1, revealing that a higher score is an indicator of a higher KSA 2030 Vision awareness. The dependent variable is the “entrepreneurial intention.” This variable is a 1-item that is measured using a four-point Likert Scale and is used to measure the extent of the students’ intention towards entrepreneurship. The four-point Likert Scale is ranging from 1 (very improbable), indicating the lowest entrepreneurship intention, to 4 (very probable), indicating the highest entrepreneurial intention. In specific, the four-point Likert Scale and the measured data have been transformed into four categories: “1” (very improbable) indicates to the very low entrepreneurship intention, “2” (quite improbable) indicates a low entrepreneurship intention, “3” (quite probable) indicates a high entrepreneurship intention, and “4” (very probable) indicates a very high entrepreneurship intention.

Simple Regression (SR) was used to evaluate the level of association of entrepreneurial intention with KSA 2030 Vision awareness. As shown by Table 4. 4, the R2 is 0.066 which means that this model has explained 6.6% of the total variance in the KSA 2030 Vision awareness.

Table 4.4 Model Summary

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate |

| 1 | .256 | .066 | .062 | .22060 |

Table 4.5 depicts that the F-value for the model is statistically significant at the 1% level which means that the overall model can be interpreted.

Table 4.5 ANOVA Analysis

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | .904 | 1 | .904 | 18.586 | .000b |

| Residual | 12.848 | 264 | .049 | |||

| Total | 13.752 | 265 |

A summary of the regression results is shown in Table 4.6. A significant negative association is present between entrepreneurial intention and awareness about KSA 2030 vision (β = - .256, t = - 4.311, P = .000, one-tailed significance). Thus, hypothesis H1 is accepted. Therefore, even though the students have a high degree of entrepreneurial intention, it is evident that they do not have lower levels of awareness about KSA 2030 Vision. The findings highlight the need for policy makers to develop strategies to increase awareness about the KSA 2030 Vision among the university students.

Implications for Management and Stakeholders

There are several implications for management and stakeholders. The fact that students have a lower degree of awareness towards the role of entrepreneurship in in the KSA 2030 Vision means that the government and other stakeholders have a lot to learn from these findings. There is a need for more awareness and educational campaigns about the KSA 2030 Vision and the role of new entrepreneurial projects in achieving these goals. Increased education and awareness can be achieved through the distribution of flyers, brochures, use of banners at strategic locations in the institution, and use of speeches and workshops that focus on major components of the KSA 2030 Vision. Changes in the syllabus could be made to include KSA vision 2030 as part of the course. Specifically, books and articles named “KSA 2030 Vision” may be added to the course and taught within the wider entrepreneurship course. If this is not enough, a course on entrepreneurship can be included as an elective course in the syllabus of the College of Business Administration. Incorporating the vision 2030 as part of the course would increase the number of students who understand the country’s plans, thereby increasing the role of entrepreneurship in building the national economy. However, those who fail to take the course may fail to get the opportunity to enhance their entrepreneurial intentions and knowledge. Adding the KSA vision 2030 plan to the relevant university requirement courses would allow students to understand concepts of entrepreneurship and KSA 2030 Vision at an early stage.

Conclusion

The objectives of this study are to explore the degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness among students in the College of Business Administration, and to examine empirically the association of entrepreneurial intention with the awareness of KSA 2030 Vision. The first objective of the study has been attained by carrying out descriptive statistics. The objective deals with the documentation of the degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness among students in the College of Business Administration. The results indicated that there is a low degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness among the College of Business Administration’s students towards the impact of the entrepreneurial project on the achievement of the KSA 2030 Vision. The third objective of the study has been achieved by conducting the Simple Regression. The objective deals with examining the association of entrepreneurial intention with the awareness of KSA 2030 Vision among students in College of Business Administration at the Northern Border University. The result indicates that entrepreneurial intention relates negatively with KSA 2030 Vision awareness.

It is worth noting that the students in the College of Business Administration at Northern Border University have a low level of awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision in terms of the impact of the entrepreneurial project on the achievement of the KSA 2030 Vision. Furthermore, entrepreneurial intention of the students relates negatively with KSA 2030 Vision awareness. The students seem to have a low degree of awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision. If awareness campaigns have been conducted to spread awareness of the concept, aim and consequences of the KSA 2030 Vision among students, the level of entrepreneurial intention would further increase within the context of achieving the KSA 2030 Vision.

This study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by providing an initial empirical link between the entrepreneurial intention with the awareness of KSA 2030 Vision among students in the College of Business Administration at the Northern Border University in several ways: First, this study adds to the recent literature by investigating and associating entrepreneurial intention and the awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision. To the best of the researcher’s awareness, no empirical evidence is available that has linked entrepreneurial intention and the awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision. Second, as a methodological contribution, the present study addresses the KSA Vision as a dependent variable, which has not been examined empirically within the framework of entrepreneurial intention.

Results from this study have several implications related to the theory. First, the results of the descriptive statistics show that the students in the College of Business Administration at Northern Border University have a low degree of KSA 2030 Vision awareness (24%) among the College of Business Administration’ students, and towards the impact of the entrepreneurial project on the achievement of the KSA 2030 Vision. This gives an alarming warning to policy makers at the university and college levels to consider spreading awareness of the KSA 2030 Vision as well as how opening new ventures can contribute to the attaining of the vision. Moreover, the Simple Regression results depict that there is a significantly negative association between entrepreneurial intention and KSA 2030 Vision awareness. This result demonstrates the fact that although students have a high degree of entrepreneurial intention, they have a low degree of awareness towards the KSA 2030 Vision. This result provides policymakers at the higher education and the university level an alarming signal regarding the policy of increasing the KSA 2030 Vision awareness among students. Therefore, the results of this study extends the previous studies related to entrepreneurship by adding new empirical evidence related to entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial education and support, and KSA 2030 Vision in the setting of Saudi Arabia. Further, studies may replicate this study to enhance the external validity of the results. Finally, it would be of interest to expand the research scope and models by using a more sophisticated technique such as structural equation modeling.

Similar to other studies, this study experienced several limitations. The results from the study are confined to the specific sample from which the data was collected (266 students from the college of Business Administration). As such, completely generalizing the findings from the study to wider populations may be challenging since it may yield different results. Therefore, it could be more beneficial to explore whether other colleges at the Northern Border University are significant predictors of entrepreneurial intention. Future studies might focus on other institutions such as the medical, engineering and humanitarian colleges. Future research could also focus on a comparative analysis to explore whether different campuses may have varying results with regards to entrepreneurial intentions. The study may be replicated in other universities within the KSA.