Introduction

Today, technology adoption in any organization or institution is understood as the dynamic capacity to gain a competitive advantage and make a difference in a sector or ecosystem. This capacity comes about through processes of exploration that lead to the development of new technologies to continuously improve the innovation procedures of any organization. An example of this is the institutions of the public security and defense sector, where police forces around the world are experimenting and adopting technologies to optimise and provide a more professional, effective and proactive service. Part of this is reflected in the use of geographic information systems for crime incidence analysis, artificial intelligence generation, more effective cameras, geolocation and recording in police procedures (Lopez & Carmina, 2020).

In addition, they use information technologies that expand the possibility of changing the form of police service with a modern vision and a technological-social approach to public safety and criminal investigation (Arenas, 2013). This leads police institutions around the world to rely on technology such as big data by integrating different sources of information, not only from the police, but also linking citizens with a collaborative approach through technologies such as the internet of things, which facilitate interaction and act in a timely manner when a criminal act is committed (Villalobos, 2020).

Therefore, in the first phase, one of the relevant aspects of the project is to involve and make citizens co-responsible in security matters, through a process of technological innovation and how this should be articulated with the police service in terms of criminal investigation. To this end, it is important to prioritize and adopt an innovation management strategy that allows for the articulation of existing capacities in order to continuously improve processes or introduce new tools that allow for positioning in the industry or sector (O’Connor et al., 2008).

For this case, the management of innovation is related to the way in which the police institution incorporates technological advances focused on radical innovation (novelty and differentiation from the existing state of affairs) (Schilling, 2020), which adds value and develops new competencies to effectively and efficiently address security challenges (O’Connor et al., 2008). To this end, it is important to create knowledge and seek adaptations to the context based on technology watch. Technology is understood as a driving force in history that interacts with artefacts in particular contexts of participation (Aunger, 2010).

In view of the above, the last decade has seen exponential growth and a remarkable acceleration of technology, due to the covid-19 pandemic, which has made it sustainable and improved people’s lives, from time savings to the implementation of new business models (Diamandis & Kotler, 2020). Many of the transformations in the security and defense sector require technologies with exponential growth, displacing others and creating opportunities to optimise processes and gain competitive advantage in the sector (Azhar, 2021). This requires a modernisation process oriented towards technological development and innovation, which links citizens in a collaborative way to effectively combat insecurity and crime in the territory (Cáceres, 2017).

Currently, security in Bogotá presents a discouraging statistical picture in terms of theft from persons. According to the National Police (2023), in 2022 theft from persons in the city registered an increase of 25.3 % compared to the previous year; in addition, 33 % of the thefts were carried out violently in the same year with the use of firearms or sharp and blunt weapons. On the other hand, there is an unfavourable index for the judicial and police authorities, and it refers to the fact that more than 50 % of the inhabitants of Bogota do not report this type of crime.

A criminological explanation of theft from persons in the city focuses on the territorial and temporal convergence of three elements: victim, offender-person and absence of guardian (Ceballos-Espinoza, 2021). This convergence generates criminal dynamics referring to economies of crime and mutations, in which the perpetrator, as an individual acting rationally, seeks to maximise his or her well-being and tries to balance the benefits perceived at the time of committing the criminal action, with the low probability of being caught (Becker, 1968).

In addition, other factors are also apparent in this crime, such as changes in intensity, new modalities and a recurrence factor in the crime. Recurrence understood as the repeated capture of an offender for the commission of punishable conduct, without being subject to a security measure (Valderrama-Cumbe et al., 2021). In the case of Bogotá, between 2017 and 2021, there were 2291 recurrent citizens arrested for theft from persons who were caught between 2 and 10 times (National Police, 2023).

The information on theft from persons and the recurrence of crime in Bogotá is used by the police institution for statistical purposes, for the construction of situational diagnoses, as an input in the construction of criminal and public policy in the country, for the planning of police service and for criminal investigation. The usefulness of this information in criminal investigation is not very efficient, as it is used by the police for statistical purposes identifying and individualising those responsible for criminal acts in the city and for optimising the investigative processes carried out by the institution. For this reason, after cross-referencing the information on theft from persons in the form of robbery with the cases in which arrests were reported from 2017 to 2021, only 6.1 % of the incidents recorded arrests (Crime Information Group, 2022).

This being the case, in this project it is important to have the context of actual crime in Bogotá. According to Restrepo (2008), this information is the sum of the recorded crime (thefts to persons reported) and the hidden crime (non-reported theft from persons).

The facts of reported theft from persons (registered crime) are known to the Attorney General’s Office (FGN) and the National Police, through the databases of each institution by two means of knowledge: the first, by the physical complaint made in police stations or in the Immediate Reaction Unit (Unidad de Reacción Inmediata-URI) of the FGN, and the second, virtually by means of the platform called “¡ADenunciar!” (Rodríguez et al., 2018), which was launched jointly by the two institutions in 2017. In recent years, this virtual platform has become the main source of knowledge for the authorities about theft from persons reported by citizens in the city (see Table 1).

On the other hand, unreported theft from persons (hidden crime) takes place in a number of countries. The project is relevant in the sense of being able to collect information that is not reported by the citizens, and that is useful for National Police investigators in the orientation of the investigation and the identification of perpetrators. To this end, it is important that both the reported and non-reported thefts from persons be collected, processed and complemented in an automated, agile and effective way with disruptive technologies in order to optimise criminal investigation in the city.

In summary, the objective of this scientific research is qualitative and focuses on managing a collaborative technological innovation process by implementing a platform to optimise police service, especially criminal investigation, by means of the correlation of unreported thefts from persons (hidden crime) and thefts from persons reported physically or virtually (recorded crime), that is, to build a collaborative security analysis model (police citizens) in which a criminal act is reported anonymously with the facility to upload audios, photos, videos and have access to the geolocation of the scene of the crime. Likewise, this platform provides useful information for citizens on issues related to crime prevention, security, traffic data, emergencies and news of interest to the police service.

The analysis of the integrated information (reported and unreported) will provide a holistic view of thefts from persons in Bogotá, which will provide detailed information in time, place and manner, to guide the investigations carried out by the National Police, offer information of interest to citizens and act proactively in the event of a criminal act., It will provide information of interest to the public and will act proactively in the event of a criminal act, with the identification, capture and dismantling of criminal gangs dedicated to this type of crime.

The information on crime recorded in the city of Bogotá shows an unfavourable scenario in terms of the rates of theft from persons, which only reflect part of the problem and have little effectiveness in optimising criminal investigation. For this reason, this research raises the following question: how to impact National Police criminal investigation with information provided by citizens in order to solve the cases of theft from persons, as well as to improve the rates of security and citizen perception in Bogota?

Finally, in this first phase, the paper firstly covers the methodology used for this research, which is deductive, based on a mapping of key actors in the project, the use of active and passive observation tools in the design and construction of user stories, hypothesis formulation, validation of the hypothesis through low and medium fidelity prototypes (experimentation) and the construction of a proposal for a collaborative system supported by technological surveillance. The second part is an analysis of the results according to the prototypes put forth, a discussion of the findings and approaches, and finalises with the author’s conclusions.

Methodology

Bearing in mind that the research is of a qualitative nature, the proposed methodology is deductive and is based on a process of sustainable technological innovation, focused on the citizen and other relevant actors in the project, with the understanding of listening and observing people in order to understand their environment (Van der Meij et al., 2016), and to be able to contribute by means of a proposal for improving the indices in security, perception and increase the rate of enlightenment in the city. This process starts with the clear idea of satisfying the citizen’s security concern, so it was important to develop design thinking through an analytical and creative process involving the acronym AEIOU (actors, ecosystem, iterations, objects and users), in order to identify opportunities and improvements in the development of the research (Razzouk & Shute, 2012).

In this first phase, the research encompasses three fundamental stages in the development of the methodology (Chun-Young et al., 2019): first, discovering the key actors in the project, what their needs, motivations and desires are, in order to build and prioritize user stories; second, understanding the strategic variables to establish a value proposition through a hypothesis and, thus, establish the appropriate experiments; finally, fashioning a solution within the framework of a technological component that aims to meet the needs of the citizen who is victim of theft from a person or who feels unsafe in the city (see Figure 1).

The first stage, called discovery, begins with an environmental analysis of the actors that influence the project; through a stakeholder mapping exercise, the 20 most important actors in the project were identified. Then, a process of active and passive observation (Martin & Hanington, 2012) is carried out to capture and analyse relevant information from citizens, the police and the offender.

For active observation, two techniques were selected: the first refers to people’s diaries (what they see and feel) and the second, by means of a rapid ethnography of the citizen (what they do and what they do not do). With regard to passive observation, two techniques were applied, as in active observation. The first, related to behavioural mapping (never stop observing) and the second, to the fly on the wall (security cameras). This process of passive observation was enriched by taking into account that any process of creativity requires thinking inside the box in the right way (Boyd & Goldenberg, 2014), i.e., the institution’s staff resources and technological means were used. Once the whole process of active and passive observation has been addressed, we proceed to elaborate the user stories as real value from the point of view of the people (Pokharel & Vaidya, 2020), which for the first case is to adjust the answers of the actors to the questions: who is the person, what attributes does he/she describe, what does he/she need to understand, and why does he/she add value to him/her? Likewise, for the second case, the procedure is similar, but a step was added, which consists of grouping tips or sentences that were related or complementary to each other in order to answer the questions that build a user story.

Once the user stories are completed, they are grouped together, a single story per stakeholder is established, validated with the final user, and people’s understanding of the stories is ensured. These steps are necessary to then weigh and prioritize the stories in two ways: how much impact on the objectives set and the level of complexity.

In the second stage, it was important to analyse the consolidated user stories, as well as carry out an analysis of the criminal and criminological trend of theft in the city over the last five years in order to establish the strategic variables that point to a more strategic approach to build the value proposition by setting out a hypothesis that encompasses what is feasible, viable and desirable in the project (Bland & Osterwalder, 2019).

Taking into account the results obtained from the user stories and the approach of the value proposition, the direction of the project focuses on a test search stage through a stakeholder-centred experimentation process with the use of low and medium fidelity prototypes (Kamthan & Shahmir, 2017); this will allow obtaining valuable and conclusive information from the users, the problem and the possible solutions that are established according to each iteration. The experimentation process was carried out using six low and medium fidelity prototypes, with the purpose of validating or refuting the hypothesis based on what is desirable, feasible and viable (value proposition), and these were established in two aspects: discovery experiments with low-fidelity prototypes, in which the project’s correct direction was validated in a basic way through discussion forums, stakeholder mapping, analysis of search trends and interviews with researchers. On the other hand, validation experiments were conducted with medium-fidelity prototypes to determine the right direction of the project through surveys and the making of an explanatory video of the value proposition (Bland & Osterwalder, 2019) (see Figure 2).

As for the validation surveys, three instruments, which were constructed using Google forms and distributed through WhatsApp chains to citizens living in the city of Bogota and who use public transport -university students, housewives and pensionersas well as to investigators of all crimes of the Criminal Investigation Directorate and INTERPOL at the national level.

The results obtained were analyzed using the Excel format provided by Google forms (quantitative answers) and, on the other hand, the use of the tool Voyant tools (qualitative responses). The latter allows for the quantification, trend analysis and correlation of words within a text, which, in this case, were all the answers to the open ended questions.

With the information collected and the results obtained in this first approach with citizens and researchers through the validation survey, we proceed to make the explanatory video of the proposal by means of the implementation of a platform to validate the hypothesis through the identification of perpetrators, solve criminal acts and improve security and perception indices in the city.

The video highlights a context, problem, environment analysis and proposal of the collaborative system between the citizen and the police, called CIUPOL; This was validated by means of Questionpro, the platform, which allows uploading the video and asking in the same view questions focused on relevance, impact and operability for criminal investigation.

Finally, the third stage for this research is to build, and it starts from a technology watch of scientific databases with an observation window of eight years, process in which delimited key words are related to criminal investigation, user, design, security, innovation and technology.

This search was necessary in the sense that police institutions are using technology as a means to pursue and bring the alleged perpetrators to the attention of the judicial authorities, as well as to seek and increase mechanisms for gathering information from the public to identify the criminal actors, their modus operandi. This will be carried out through the dissemination and use of inclusive technological information tools, with special usability features, which will serve as input for investigators in judicial proceedings and, subsequently, as physical evidence and material evidence in an oral trial hearing.

In this sense, the project raises the possibility of building a collaborative system in criminal investigation between citizens and the police, using a process of technological innovation that meets the need for security and perception in the city. The project proposes the possibility of building a collaborative system in criminal investigation between citizens and the police, using a process of technological innovation that meets the need for security and perception in the city, due to the lack of modern mechanisms that allow citizens to communicate effectively and quickly with security agencies for the identification of criminals and the timely intervention by the authorities in the face of criminal acts with the use of appropriate and effective technologies (Tundis et al., 2021).

Results

This section shows in detail the analysis and achievements for the stages established in the methodology that frames the project, starting from the observation and understanding of the actors, through experimentation to the proposal of a collaborative system with a disruptive technological component.

In the discovery stage, it was necessary to map the actors through a discussion forum with the work team of the Forensic Neuroscience Laboratory of the Directorate of Criminal Investigation and INTERPOL (DIJIN), where twenty actors with a direct influence on the project were initially identified: Presidency of the Republic of Colombia, Ministries of National Defense and Information Technologies, Attorney General’s Office, Secretariats of Security and Mobility of Bogotá, National Planning Department, National Registry of Civil Status, National Penitentiary and Prison Institute, National Police, University of the Andes, international police (AMERIPOL), analytics and technology companies, Migration Colombia, media, US Embassy, citizen, offender, Attorney General’s Office and research centres. A second iteration of the discussion forum was then necessary, and by weighting, three actors were selected: citizen, National Police and perpetrator.

These actors were taken into account in order to employ, in the first instance, two active observation tools (diary and rapid ethnography), using questionnaires to collect information from the citizen and the police: university students, taxi drivers, housewives and pensioners, passengers on daily public transport and judicial police investigators. In addition, it was necessary to collect information from a perpetrator or offender through a search and analysis of structured information in the media, official statistics and interviews with experienced police officers in criminal investigation and the intelligence of the National Police.

The questions set out in the questionnaires were intended to construct user stories for the three actors to help understand a little about who they are, what they do and how each one behaves. The questions were designed to identify demographic and psychological characteristics, what their needs (ailments) and expectations (what they expect) are with regard to the theft issue (Gaver et al., 1999).

As for the two tools used for passive observation (behavioural mapping and fly on the wall), it was necessary to carry out an intervention with five laboratory assistants, who for one week recorded on a daily basis the behaviour of the people and other aspects that were most important to them. The laboratory assistants recorded people’s behaviour and other aspects they noticed on the streets as they travelled from their homes to the office and vice versa (morning-evening and midday), during the week, by different routes and in their means of transport (motorbike and bicycle). In addition, three external security cameras were analyzed for twelve hours, located in the DIJIN of the National Police. The recordings analyzed correspond to the Modelia neighbourhood during peak hours (busiest times) between Friday and Saturday.

Thus, once the two observation tools (active and passive) had been applied and the information relevant to the project had been collected, the following nine groups were identified for the three selected actors: citizens (university students, housewives and pensioners, company workers, bicycle users and motorcyclists, public transport users and taxi drivers), police (surveillance patrols and investigators) and offenders (those caught) (see Figure 3). Fifty-four user stories were then constructed for the three and we proceeded to validate and consolidate these stories into only nine user stories.

Now, for stage two, understanding, it was necessary to carry out an analysis of the nine consolidated user histories and criminal statistics on theft from persons in Bogotá for the last five years. The analysis of the user stories was captured on a user profile canvas, associated in four groups (university citizen, citizen using public transport, police investigator and captured offender).

These results were complemented with the trend analysis of criminal statistical information regarding variables such as modality, locality, neighbourhood, time of day, area, mobility of the offender and age and gender of the victim. Based on this, more concrete data was obtained, which made it possible to establish the value proposition through a hypothesis based on what is desirable, viable and feasible, that is to say, from identifying the perpetrators, solving the criminal acts and improving the indices of security and citizen perception. Therefore, the hypothesis put forward is the following: “The information provided by citizens contributes to the timely identification of perpetrators in order to solve criminal acts and improve security and citizen perception indices in Bogotá”.

As for the hypothesis validation process, discovery experiments have been carried out in the discovery stage of the project methodology, to understand the actors through observation tools, build user stories and identify strategic variables for the value proposition approach.

For the validation experiments, as far as the surveys were concerned, three types of instruments were applied addressed to two actors with four groups: the citizen(university students, pensioners, housewives and public transport users), and the police (investigator). The surveys were carried out among 349 people (citizens and investigators of all crimes) and made it possible to test the hypothesis based on what is desirable and feasible, that is to say, citizen perception and safety, as well as the agreement to provide information to the National Police in order to identify the alleged perpetrators and the type of information to be provided. The following are some important results of the three instruments applied.

Validation survey carried out with citizens who use public transport and housewives and pensioners

The survey was carried out among 55 people from the localities of Engativá (11), Usme (9), Ciudad Bolívar (6), Usaquén (4), Suba (4), San Cristóbal (3), Kennedy (3), Bosa (3), Fontibón (3), Teusaquillo (2), Bosa (3) and Teusaquillo (2)., Los Mártires (2) and other localities (5).

According to the question chat, is the biggest security problem in the place where you work or travel? Those who responded indicate that 80 % of the security problems are centred on theft from persons and theft of mobile phones (see Figure 4).

In addition, 41.8 % indicate that the most insecure environments are public transport, establishments open to the public and the streets, with 16.4 %, respectively.

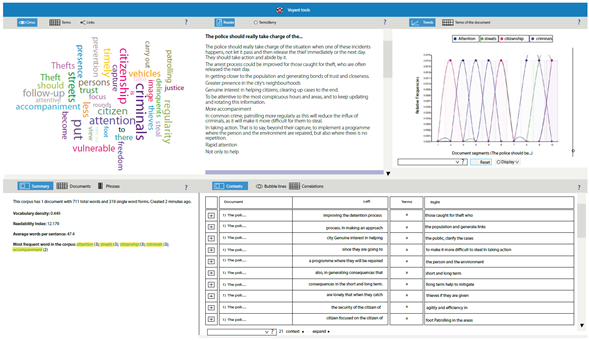

In addition to the above, they were asked: “What is the best way to get a better idea of what is going on? Why do citizens not provide information of interest to the institutions to guarantee social order and improve security conditions in the city? To which they responded that this is due to issues of fear (intimidation or threats) that providing information could cause problems in the future; the difficult processes (paperwork) to provide information and lack of trust in the entity; lack of knowledge or little information to access channels to provide information; the information provided is not taken into account or nothing is done with it. These types of responses were analyzed using Voyant tools (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Analysis of the question: Why do you think that citizens do not provide information of interest to institutions to guarantee social order and improve security conditions in the city?

On the other hand, the communication channels preferred by respondents to provide information about criminal acts in their environment are: mobile applications with 34.5 % (19), WhatsApp group with 21.8 % (12), a phone call with 16.4 % (9) and a visit from uniformed officers to collect information with 10.9 % (6). Similarly, 87.3 % of the respondents would agree with collecting and sharing information with the institution

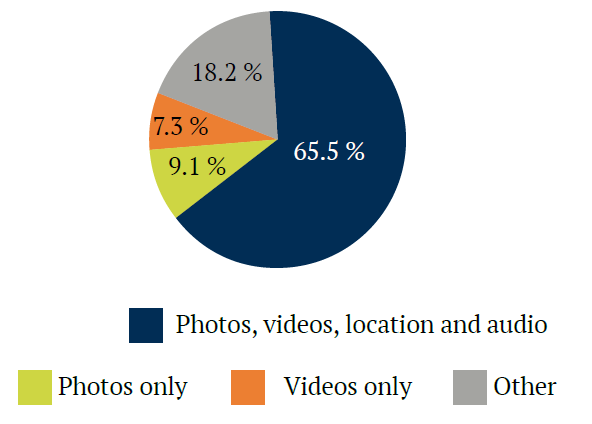

The type of information they would share would be photos, videos, audios and the geographical location of the event (see Figure 6).

University citizen validation survey

The survey was validated with 48 university students surveyed, from the localities of Usaquén (9), Suba (8), Engativá (7), Teusaquillo (4), Kennedy (3), Ciudad Bolívar (3), Puente Aranda (3) and other localities (11).

University citizens state that the crimes that most affect their environment are theft from persons 54.2 % and theft of cell phones 33.3 %. Likewise, 31.2 % feel vulnerable on avenues or streets (bicycles or skateboards and pedestrians or passersby) (see Figure 7).

In addition, the most common means used by criminals are motorcycles 68.8 % and pedestrians 18.8 %.

According to the respondents, in order to improve the city’s perception and security indices, the National Police should focus on: timely attention, agility and efficiency; articulating the capacities of the entities involved; improving the presence of uniformed personnel; active prevention work and rotating securitysurveillance patrols; citizen security, focusing on the control and follow-up of calls made by citizens; outreach to the population in order to improve in generating and dismantling criminal organisations (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 Analysis of the question. From your point of view, on what should the National Police focus its efforts to improve the city’s security and perception indices?

Another relevant question is that respondents indicated that they would be willing to collect and share with the National Police in order to improve criminal investigation and be able to solve cases of theft from persons in the city.; 43.8 % of respondents (21) would provide photos, videos and locations (coordinates or addresses); 16.7 % (8), only videos; 12.5 % (6), only photos, and 10.4 % (5), only locations (coordinates or addresses).

Researcher validation survey

This survey was validated with 246 judicial police investigators from all over the country, with time in the institution of more than 15 years 29.3 % (72), from11 to 15 years 28.5 % (70), from 1 to 5 years 22.4 % (55) and 6 to 10 years 19.9 % (49).

The investigators state that in their daily work they encounter prosecutors with little experience or knowledge needed to perform their work: No, 65 % (161) and Yes, 35 %.

71.9 % indicate that the components that hinder their functions in the research processes are logistical and technological (see Figure 9).

On the other hand, the researchers indicate that the most relevant elements for improving citizen perception are having a greater amount of information to be analyzed, approach towards to the community, better preparation of the police, strengthening research and better information for decision making (see Figure 10).

Figure 10 Analysis of: What is the most important element that you consider should be taken into account when improving the public’s perception of security?

On the other hand, the explanatory video was validated with 186 people, 122 citizens from different groups and 64 investigators of the crime of theft from persons. Its purpose was to test the viability of the CIUPOL platform for optimising criminal investigation, by identifying actors and the means to capture information for the dismantling of criminal gangs. The results are as follows:

Explanatory video validated with citizens

The citizens surveyed indicated that 89 % would use CIUPOL in the future from their mobile phones to report timely information on videos, audios, location and photos of criminal acts in Bogotá.; 6 % say maybe and 5 % say no.

On the other hand, the platform will have a 69 % impact on the identification of criminals and a 68 % impact on the improvement of security and perception indices in the city (see Table 2).

In addition, citizens indicate that other aspects that the platform should have are: that it allows to generate personal alarm at the moment the incident occurs; to report in real time the criminal events to the nearest police station, CAI or quadrant; that generates anonymity for the people who provide information; it is necessary to consider scenarios and places in which people lack access to data or internet; allow reporting other risk factors that facilitate crime, such as lack of lighting, suspicious persons or activities, sale of drugs, among others, and allow recording the location of private surveillance cameras (houses, companies, businesses, premises, among others), which subsequently help in the investigative processes to locate routes of movement and identification of perpetrators quickly.

On the other hand, it is important to consider strategies to link other actors, taking into account that one of the main factors why people would not use the platform would be not having access to internet or data (see Table 3).

Similarly, the elements or characteristics that should be taken into account to strengthen the CIUPOL platform and allow for the identification of perpetrators and at the same time improve security and perception indices are focused on the relationship that should exist between the information provided and the impact of the information, as well as feedback to citizens on what was done with the information; a dissemination campaign and presentation of the positive results provided by the tool, a report of criminals captured and imprisoned thanks to the application and citizen collaboration; includes a panic button and real-time and exact location of the victim; an outline of criminals for citizen visualisation; free of charge; permission to use the platform at no cost; dual authentication of users for responsible use; incentives for users who provide vital and timely information; creating links between citizens and police.

Explanatory video validated with investigators of theft from persons

69 % of investigators would use CIUPOL as a technological alternative to analyse information to optimise investigations into cases of theft from persons in Bogotá, 20 % would not use it and 11 % might use it. In addition, the usefulness of the platform is focused on a 50 % in criminal investigation and the other half on reporting issues and improving security and perception indices in the city (see Table 4).

According to investigators, other types of information that citizens would be willing to report are mobile phone numbers, family locations and places used to store stolen objects or places where criminals hide or frequent; indicate social networks of the people involved (criminals and suspects) and places where drugs are sold (fixed and mobile).

The most relevant information in investigations for the identification of perpetrators, which is collected by the citizens, is focused on videos and images, with 97 % (see Table 5).

On the other hand, the researchers indicate that it is important to take into account other elements or characteristics of CIUPOL to optimise criminal investigation. These are related to providing the full names of the offender; cross-referencing the information with the Automated Biometric Identification System (ABIS) of the National Police; creating a module where citizens can easily communicate with investigators; information endorsed by the Attorney General’s Office as evidence and that the chain of custody is guaranteed; using the tool without the need for internet or data; having operational criminal investigation personnel available to deal with cases reported on the platform and thus being more effective in serving the community; and socialisation of the tool with both with citizens and investigators.

Finally, and taking into account the results obtained in the discovering and understanding stages, in the case of building, it was important to carry out a technology watch process with an observation window of eight years, in order to determine which is the most viable and sustainable solution in the medium term, which will satisfy the security needs of the city, with timely information for citizens and which will lead to the identification and capture of perpetrators.

This search identified five disruptive technologies with applicability to issues of criminal investigation, security and citizen participation: internet of things, GPS, cloud computing, big data and artificial Intelligence (AI) (see Figure 11). In this sense, the implementation of technologies such as the internet of things in the police service is used as a social device to support the detection and tracking of criminals around the world (Tundis et al., 2020). These systems are computing devices that interrelate with each other to identify and transfer data across a network without requiring human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction.

On the other hand, the use of new devices such as smartphones and web applications plays a preponderant role in improving security systems, crime analysis and emergency situations; that is why the use of technologies such as GPS provides information on the commission of criminal acts and places of intervention, such as monitoring the behaviour of perpetrators and citizens (Keatley et al., 2021). Today, many people are connected physically and virtually, monitoring what is happening in their environment in terms of security; therefore, they become a kind of “guardians” that can feed a system with photos, videos, audios or any type of information that can be useful for police authorities and that, when uploaded, automatically captures the latitude and longitude (coordinates) of people (Elnas et al., 2015); this can improve the response and investigation rates of police forces.

There are technologies that facilitate the interaction with mobile and computing devices, as well as their location, depending on the time factor and the crossing of information according to an architecture based on the cloud or cloud computing (Rawashdeh et al., 2021; Yin, 2022). Thus, the context of criminality can be understood efficiently and with a more effective intervention, if there are technologies that contribute to the interaction between so-called social devices and their exchange of information in real time (Tundis et al., 2021).

Similarly, there is another type of technology that is important for the development of the research proposal, and that is related to big data, its applicability and complementarity with artificial intelligence. The big data approach is based on the analysis of large amounts of data, based on visualisation, information extraction and crime prediction, together with data mining (Feng et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2018); it is also defined by the ability to efficiently store, manage and process relevant and accurate information for police investigators and analysts (Pramanik et al., 2017). As for artificial intelligence, used by police forces to save time through machine learning processes, optimisation in search methods and algorithms for the taking of effective and secure decision-making with cloud-based information and internal databases (Müller et al., 2020; Rahmani et al., 2021), which allows for crime prevention information, alerts at critical points, and provides inputs for investigative and police intelligence activities (Lira & Fuentes, 2021).

Based on the prioritisation of the technology watch analysis, literature and of the results of the experiments, a collaborative system focuses on the citizen as victim/ witness and victim is established for this first phase of the project (see Figure 12), which, by means of disruptive technologies, allows for the capture, processing and analysis of information provided by the citizen on the crime of theft from persons (reported and unreported), and this will make it possible The police institution can make timely, proactive, social and effective decisions to contain the phenomenon of crime in the city.

The collaborative system is an artefact that has a purpose to impact on a specific issue: security, and moreover, optimise criminal investigation in Bogota for theft from persons; and; moreover, it is an innovative system with a social focus (Olaya, 2013) that starts with the information provided by the citizen (reported and unreported theft from persons) and ends with the feedback of the information processed for the benefit of the citizen in terms of security and crime prevention in the city. This is nothing more than the design, articulation and execution of coordinated actions and strategies with the same purpose, which is to transform citizen security and perception into better indicators for the city, as well as the identification of perpetrators for their capture and the dismantling of criminal organisations.

Discussion

Currently, the indicators of exaggerated increase in urbanisation and the rapid expansion of urban centres that house a large number of people, as is the case of Bogota with a population of approximately eight million inhabitants, creates correlation problems such as crime and insecurity factors in public spaces (Mondal et al., 2022); in this aspect, as there is this urban expansion and environmental reconfiguration of cities (green areas, parks, commercial areas, tourist sites), the temporary or partial increase of people in these places results in the visit of many people in these local places (floating population), which also facilitates the occurrence of frequent crimes in the city (Kiran et al., 2022), for example, theft from persons.

The cases of theft from persons have led the Metropolitan Police of Bogota to employ a whole range of possibilities (investigation and police intelligence methods, analysis of video cameras, collection of technical-scientific evidence, prevention activities, among others) to interpret the needs and ailments of citizens as victims or witnesses (Caminha et al., 2017; Cheng & Williams, 2012), as well as to act proactively in the prosecution, identification and prosecution of perpetrators as alleged perpetrators of these events in Bogota.

This understanding of the citizen has led the police to focus their efforts on a linear (case-effect) way on methods to collect, process and analyse data such as photographs, audios, videos, texts and geo-referencing, making use of information provided by different users through collaborative systems without taking into account the feedback of the same information. For example, mobile applications with direct access to emergency information, crime and disaster tracking, provision of ambulance, fire and police services (De Guzman et al., 2014).

Taking into account the above, the project hypothesised that the information provided by citizens in a timely manner would contribute to the identification of perpetrators of theft from persons, in order to clarify the facts related to this crime, and, thus, improving security and citizen perception indices in Bogota. To this end, a citizen-based methodology was designed, with the identification of key actors for the project and the application of prototypes that allowed the hypothesis to be validated, and finally a first proposal for a collaborative system with a social focus under a technological component suitable for the project’s objective.

In this understanding, the results obtained through the developed prototypes validate the hypothesis based on what is desirable, feasible and viable, for a first phase as mentioned in this document; however, the technological tools established for this proposal may fall short at the time of crossing spatial information for the identification and monitoring of criminal actions. In this case, Patil (2010) mentions the use of crime mapping and hotspot detection as an essential element to manage/eliminate the occurrence of crime. This is a very important aspect to take into account in the proposed collaborative system, due to the process of data capture and strategy in order to optimise criminal investigation and ensure the safety of the citizens of the city of Bogota.

In this regard, the use of complementary georeferencing tools is necessary for the process. In this sense, the use of complementary geo-referencing tools is necessary for the processing and analysis of thefts from persons (reported and unreported), in order to identify the critical areas of the city where crime is most prevalent, which will allow mapping spatial distribution and make effective decisions to anticipate crime. In other words, it is important to complement the analysis of information collected in the collaborative system with geospatial data from other information sources., as suggested Wang et al. (2013), who conducted a comparison between spatial tools to obtain more accurate results with good data recording and high fidelity in the accuracy of the crime event.

In addition to the above, another technological alternative that would strengthen the social collaborative system refers to the linking of surveillance or security cameras in the city for the identification of vehicle license plates by means of real-time image processing computer techniques, also known as number plate recognition, which are highly productive technologies of great interest for criminal investigation in the city (Kiran et al., 2022).

These ways of capturing, processing and crosschecking information by police forces have become a way to anticipate and innovate in the service of identifying criminals, based on a participatory context of the citizenry in providing timely and valuable information in order to enrich and strengthen criminal investigation in Bogota. This, in turn, has a positive impact on the citizen’s trust in the institution in the way of improving internal procedures to act, and not so much in the results obtained.

On the other hand, it is important to consider for the collaborative system the way in which this collected information (reported and unreported theft from persons) should be processed and analyzed, which should generate comprehensive knowledge of the criminal event that has occurred (Pérez et al., 2021). This is done through the implementation of other technological tools such as data mining and machine learning, which allow coding and automating the information collected from different sources into a single unit, and this in turn facilitates the integrity and cleaning of data for effective decision making by the institution.

That is why the architecture of the system must be oriented to the different tools and components that intervene to accelerate the collection and processing of information, which will later be known in the research processes, through the successful integration of massive data flows from different sources.

In addition, it is important to consider that an application of these characteristics must provide modules to organise and classify the information and that are interconnected, not so much for the citizen who supplies the information, but for the institution that must analyse and operationalise it, including: visual intelligence, representation and semantic fusion, trend detection and prediction, among others.

These modules are the component that is being enriched with the analysis of human actions, recognised by addressing different aspects such as the value that can be extracted from the information collected from different sources; the development of algorithms that allow for the recognition and facial detection of people and objects contained in images or videos, considering the place and time where it is recorded; transformation of the information into valuable knowledge that comes from sources such as: geospatial data, web data, data from darknet, video/image data, road traffic data, financial data, telecommunication data, social networks, data and information systems and data security; creation of datasets by applying data analysis techniques of big data analysis techniques to identify hidden trends, for the purpose of predicting behaviours and actions; application and algorithms of machine learning and artificial intelligence (Demestichas et al., 2020).

The discussion on the subject is broad, diverse and, above all, constantly growing, paving the way for the implementation of innovative and disruptive technologies that contribute to a significant improvement in the mechanisms of analysis, processing and production of knowledge, in the field of security and the prosecution of the possible criminal actor involved, through the rapid identification of the alleged perpetrator or person responsible for the theft from persons.

The continuation of the project consists of: (a) complementing technology watch with other tools that will enable the collaborative system to be more efficient in decision-making; (b) link other actors with a social responsibility approach. For example, mobile phone operators, so that people can deliver information without the need for the Internet or to those who do not have connectivity; (c) evaluate CIUPOL features with high-fidelity prototypes; and (d) complement the first results of the proposal with system dynamics, as the technique for understanding and making effective decisions in complex social environments or systems. Finally, once the aspects of the second phase have been developed and evaluated, it is necessary to carry out a third phase, focused on a pilot test to diversify the proposal in relation to other crimes in the city or, perhaps, massify it for other major cities with a problem similar to that of theft from persons in Bogotá.

Conclusions

This research shows that -although there is a latent problem in terms of the rates of insecurity due to cases of theft from persons in Bogotá, as well as the low effectiveness of the criminal information reported in investigative matters and a high percentage of non-reporting of these incidents to the judicial and police authorities. -there are technological innovation projects in the world for emergency cases that can be adapted to the security and defense sector, especially to the criminal investigation processes of the National Police, with the purpose of optimising them through the timely and efficient identification of perpetrators, in the clarification of criminal acts for theft from persons and in improving security and perception indices in the city.

In the development of the project, it is evident that it is in a first phase, with a large amount of information collected and validated with actors, technologies and experiments carried out to obtain data that allowed to determine the right direction of the research and the steps to follow in the future. This leads to the implementation of an artefact with a social focus that materialises the effort not only of the police but also of the police institution itself. This leads to the implementation of a socially focused artifact that materialises the effort not only of the police institution when collecting and processing criminal information to counteract crime, but also of the citizenry when capturing and delivering the information in a timely and efficient manner to the police.

Thus, the context analysis for the project revealed an opportunity because the usefulness of information systems and the applicability of technologies in security matters is carried out for emergency purposes and not for criminal investigation, i.e., once an event occurs, police authorities are informed to coordinate, depending on the case, to call the ambulance or the fire department or the surveillance patrol to arrive at the scene of the incident in a shorter period of time.

In addition to the above, with an observation window of eight years in a process of technological surveillance with the use of keywords such as user, design, criminal investigation, innovation and technology, it was possible to identify and prioritize five disruptive technologies applicable to the project. This finding starts with the way of capturing information through the internet of things, then with the process of delivering information through GPS (coordinates), then with the consolidation of information in a cloud (for both reported and unreported thefts), followed by the processing and analysis of the information collected through big data and, finally, the automation of processes with artificial intelligence.

In this context analysis it was necessary to carry out a low-fidelity prototype by mapping the actors that influence the project in order to validate the hypothesis based on what is desirable; 3 actors were selected: citizen, police and victimiser. With these actors, 54 user stories were constructed in 9 groups through the use of observation tools used in the design, where 5 interviews were applied, 30 instruments were used to collect information and 12 hours of video from security cameras of the National Police of Colombia were analyzed.

On the other hand, the hypothesis was validated as feasible with a medium-fidelity prototype. This was done through validation surveys (3 instruments) with citizens and police investigators. The instrument showed that 87 % of the respondents would collect and hand over information to the National Police and the type of information would be 55 % videos, audios, photos and location; on the other hand, the researchers indicate that 72 % of the respondents would collect and hand over information to the National Police which hinders the investigative process related with logistical and technological aspects.

Once the results of the surveys had been analyzed, another validation of the hypothesis was carried out based on what was desirable, viable and feasible for the actors., and this was by means of a mediumfidelity prototype. In this case, it was the explanatory video of the project’s value proposition. This validation was carried out with 186 people (122 citizens and 64 shoplifting investigators). The results were as follows: 89 % of citizens would use the CIUPOL collaborative system from their mobile devices. On the other hand, they indicate that the impact that CIUPOL would have would be 70 % in identifying criminals, 68 % in improving security indices and citizen perception and 88 % that the information would be useful for them in security and prevention issues; and as for the investigators, 69 % would use it for their investigative processes and 50 % indicate that it would optimise criminal investigation by identifying criminals and in the dismantling of criminal gangs.

With all the information gathered and the results obtained, we propose a collaborative system (citizens Police) with a social focus, which allows the information provided by citizens (reported and unreported theft from persons) to be captured, consolidated, processed, analyzed and automated by the National Police for three purposes: The first is to improve crime prevention processes; the second is to provide people with useful data on security and prevention; and the third is to optimise criminal investigation by identifying perpetrators.

Fortunately, these innovation processes today veil a problem and multiple ways to solve it, which, for this case, is no exception, and there are different technologies to carry out a scenario of applicability and implementation: the collection, processing and analysis of all information, and therefore it is important to recognise that the current technological universe is in constant development and evolution. This leads the National Police not only to venture into innovative tools such as CIUPOL, to control the flow of information subject to scrutiny by the competent authority, but also to discover, relate and correlate information on unreported theft from persons with other heterogeneous sources of information.

This proposal leads to the fact that, although CIUPOL is an excellent alternative to favour the police service, it is important that the information provided by the system’s stakeholders can be analyzed using tools such as system dynamics to understand the different feedbacks over time from the stakeholders and their impact on the researchers’ decision-making for the proposed collaborative system.1