In the context of dynamic social and economic changes, consumer brands increasingly focus on providing pleasure to consumers by designing their sales processes to offer some degree of excitement, whether for functional or recreational motivation (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2021; Iyer et al., 2020; Kaltcheva & Weitz, 2006). Consumers have abstract and complex purchasing motivations, which can impact both the perceived quality of items and future purchasing intentions (Tena-Monferrer et al., 2021).

Nonetheless, the role of utilitarian, hedonic, or ethical motives in shopping still deserves advanced investigations (Iyer et al., 2020; Tena-Monferrer et al., 2021). Utility is related to the functional benefits of products and is based on situational factors, on the other hand, hedonism is more reflective, related to pleasant experiences, and based on cognitive factors (Chang et al., 2023). Ethical motives, in turn, occur when consumers recognize that they are contributing to a noble cause while enjoying the shopping experience (Tena-Monferrer et al., 2021). While there are a variety of motivations for consumption, the hedonic premise of joy and pleasure (Tiwari et al., 2020) is a particularly relevant lens for examining specific purchasing behaviors.

Considering that hedonic consumption provides pleasure, recreational benefits, and emotional value, it can strongly affect an individual's purchase intentions (Babin & Babin, 2001; Vieira et al., 2018). Research on this topic has been conducted in the areas of marketing, strategy, and retail (e.g., Alba & Williams, 2013; Babin & Babin, 2001; Babin et al., 1994; Chang et al., 2023; Tena-Monferrer et al., 2021). However, relationships among hedonic motivations, personality characteristics, impulsive buying tendencies, and specific buying behaviors have not yet been explored.

The present study advanced the field of shopping behavior by simultaneously investigating hedonic consumption motivations and their associations with individual and behavioral variables in the Brazilian context. This context and culture differ from the mainstream research area, which is generally characterized as Western, educated, industrialized, wealthy, and democratic (WEIRD) (Cheon et al., 2020).

Purchase motivations

While utilitarian motivation for purchasing generally includes formative evaluations such as the price, the product quality, convenience, or the efficiency and effectiveness of the process; hedonic motivations are a reflective construct related to curiosity, joy, immersion, and temporal dissociation (Chang et al., 2023). Utilitarian purchases are made when individuals primarily seek functional benefits or economic value in their purchases (Chang et al., 2023; Okada, 2005; Voss et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2022); whereas hedonic purchases are marked essentially by pleasure, entertainment potential, and emotional value that are associated with the shopping experience (Babin et al., 1994; Chang et al., 2023; Kumar & Noble, 2016; Muruganantham & Bhakat, 2013).

Thus, the main characteristics of hedonic purchases can be defined as emotional, sensory, and fanciful aspects that individuals seek while shopping (Alba & Williams, 2013; Babin et al., 1994; Childers et al., 2001; Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000; Hirschman & Holbrook, 1982). Hedonic consumption is also linked to aesthetic and pleasurable aspects of the shopping experience itself (Jones et al., 2006; Matos & Rossi, 2008; Tena-Monferrer et al., 2023). These aspects can create high levels of perceived value in the shopping experience because they offer more recreational benefits and pleasure (Hirschman & Holbrook, 1982; Kaltcheva & Weitz, 2006; Tena-Monferrer et al., 2023).

The multiple motivations that spur people to go shopping were captured on a scale that was developed to address hedonic reasons for consumption behaviors, including experiential and emotional aspects (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003). Babin et al. (1994) initially developed a scale to measure hedonistic and utilitarian values that are attained through the shopping experience. These authors identified two explanatory dimensions, showing that consumers perceive purchases in both utilitarian and hedonic terms. Their approach recognized that not every consumer behavior implies satisfying functional or utilitarian needs-they also entail emotional motivations. Hassay and Smith (1996) sought to holistically describe reasons for purchasing based on an analog test that employs a projective approach whereby participants should think about an animal that would best describe them as consumers. Afterward, Voss et al. (2003) extended previous studies by developing a new instrument that measures hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitudes, based on semantic differential items that specifically refer to product categories and different brands within each category. Kim (2006) also suggested an understanding of hedonic and utilitarian motivations that underlie purchases but did not propose a measurement instrument.

Arnold and Reynolds (2003) proposed an instrument that measures hedonic motivations for purchases. This instrument provided a basis for investigating interrelationships among hedonic motivations, consumer experiences, shopping results, and specific behaviors. The scale consists of 18 items that can be explained by six factors that represent individuals' hedonic motivations: Adventure Shopping, Gratification Shopping, Role Shopping, Social Shopping, Value Shopping, and Idea Shopping.

Adventure Shopping. Hedonic products can trigger an affective and sensory experience that involves aesthetic pleasure, fantasy, and even fun (Büttner et al., 2014; Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000). Adventure Shopping as a motivation is characterized by sensory stimulation that produces hedonic value for purchases. Experiencing various sensations during shopping is an element that is present in individuals who adopt a recreational and playful approach to shopping, seeking both stimulation and entertainment (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Kaltcheva & Weitz, 2006).

Gratification Shopping. Any shopping activity can serve as an escape and therapeutic experience, providing beneficial tension relief and a way to face and respond to stressful events (Guido et al., 2007). When individuals find motivations to buy to cope with negative emotions or take their mind off a problem, shopping is seen as pleasant and stimulating. This perspective of motivation is based on the idea of raising one's spirits or indulging in self-gifting during shopping (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003).

Role Shopping. Social aspects are also sources of hedonic motivations for shopping. Pleasure lies in fulfilling one's social roles in the shopping activity, such as when one rejoices from performing the task of seeking an ideal gift (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003). Role Shopping is hedonic motivation for shopping, based on the satisfaction of buying for others. The sense of accomplishment and duty that is fulfilled is hedonic motivation for individuals who like to optimize their choices, which they do when searching for the right product for the right person (Westbrook & Black, 1985).

Social Shopping. Studies indicate that shopping can also act as a pastime that is enjoyed with family and friends. Some people invest in social interaction while shopping, motivated by the opportunity to socialize with other people (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003). Previous studies of hedonic shopping identified this category of behavior, in which shopping is described as an ideal context for socializing, even with other buyers (Dholakia, 1999; Guido et al., 2007; Westbrook & Black, 1985).

Value Shopping. In addition to personal benefits and social factors, hedonic motivation for purchases can be generated by the value of the product itself. In this case, purchases whose main characteristics are good prices from the perspective of the buyer are sought. Some people derive pleasure from searching for discounts and low prices that provide strong motivation (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Dholakia, 1999; Guido et al., 2007; Westbrook & Black, 1985). Bargain shopping can also be perceived as a challenge to be met. When a buyer finds the right price, the individual feels satisfaction as a personal achievement. In this type of motivation, cost is considered a logical and efficient aspect of buying pleasure (Kaltcheva & Weitz, 2006). These consumers tend to be more oriented toward the feeling of efficiency in the act of buying. This efficiency is perceived by their potential to bargain with sellers and discover discounts (Büttner et al., 2014; Guido et al., 2007; Westbrook & Black, 1985).

Idea Shopping. One way to achieve satisfaction and pleasure with purchases is by the acquisition of novelties. People who follow new trends and innovations are often more motivated to keep up with new product releases and tend to always look for information on recent updates to their favorite shopping focus (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003).

Therefore, buying behaviors are not only determined by circumstantial resources, such as time or money, but also impacted by hedonic motivations and such traits as the search for sensations or self-control (Seinauskienè et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2022). Understanding that individual differences can also influence motivations and different everyday situations, personality factors have been studied mainly as an intrinsic component of consumer behavior (Aquino et al., 2019; Egan & Taylor, 2010; Sofi & Nika, 2016; Thompson & Prendergast, 2015).

The Big Five Factors (Big5) perspective is a trait model that presents a reasonable degree of consensus and stability, covering observable, environmental, and biological variables (Natividade & Hutz, 2015; Pervin & John, 2009). According to the Big5 model, human personality can be understood through five independent factors (John et al., 2010): Extroversion -a tendency to seek stimulation in interaction with others, to be active and communicative; Agreeableness -a tendency to demonstrate empathy, altruism, and prosocial behaviors; Conscientiousness -a tendency to self-control when carrying out tasks that lead to a goal, to be disciplined and organized; Neuroticism -a tendency to demonstrate emotional instability, experience negative emotions, anxiety, depression; Openness -a tendency to try new things, to demonstrate curiosity and intellectual complexity (Natividade & Hutz, 2015).

Despite a number of studies on the relationships between the Big Five and various shopping behaviors (Aquino & Lins, 2023; Otero-López et al., 2021; Thompson & Prendergast, 2015), there is still a dearth of research showing correlations between hedonic shopping motivations and the Big Five factors of human personality. Among them, relationships between Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Extraversion with hedonic shopping dimensions have been identified (Guido, 2006; Guido et al., 2007; Guido et al., 2015; Mooradian & Olver, 1997; Tsao & Chang, 2010).

Understanding the degree to which someone makes purchases that are stimulated by sensory stimuli expands as we delve into studies of hedonic motivations for purchases (Beatty & Ferrell, 1998; Rook, 1987). From this perspective, hedonic or utilitarian motivations can potentiate the tendency to buy on impulse, which is defined as the degree to which an individual is susceptible to making purchases that are not well thought out, stimulated by appeals that are generated by physical proximity to an object under the pretense of receiving immediate gratification (Rook & Fisher, 1995). Although personality is also a determining factor in impulsive buying (e.g., Aquino et al., 2019; Bratko et al., 2013; Thompson & Prendergast, 2015), the role of personality traits in the purchasing decisions of a consumer is still inconclusive (Aquino & Lins, 2023; Olsen et al., 2015).

The present study adds to the literature by adapting to the Brazilian context an instrument that is useful for measuring an essential construct of social psychology studies that is applied to consumption, namely the Hedonic Shopping Motivations (HSM) scale. To date, few studies have provided evidence of the validity of this instrument in other contexts. For example, we found adapted versions of the HSM scale with Portuguese and South African samples (Cardoso & Pinto, 2010; Dalziel & Bevan-Dye, 2018). To contribute to studies that adapted a relevant instrument for research on motivations and consumption to the Brazilian context, the present study tested correlational and prediction patterns of motivations for buying behaviors and impulsive buying while controlling for personality factors.

So, even though previous research has explored associations between impulsive buying and the big five, besides others that have shown that HSM and impulsive buying are related (Mamuaya & Pandowo, 2018; Widagdo & Roz, 2021), this study considers the three constructs integrated. It is proposed an advanced knowledge personality, motivations, and behavior consumer. The results of this study could reveal new research avenues in various fields, in addition to identifying hedonic motivations that predict behavioral variables and individual dispositions.

The Present Study

The present study tested the explanatory power of the HSM scale for impulsive buying tendencies and specific buying behaviors, in addition to presenting psychometric properties of the Brazilian-adapted version of the HSM scale.

Method

Participants

The participants were 429 Brazilian adults, with a mean age of 34.5 years (SD = 14,6; Min = 18, Max = 80), 73,7 % of whom were women, and 26,3 % were men. The sample included people from all states in the country, with 88,1 % of respondents being from the Southeast region; 5,8 % from the South region; 2,7 % from the Northeast region; 1,1 % from the Midwest region; and 0,5 % from the Northern region of Brazil, besides 1,6 % of respondents living abroad. Of the total sample, 0,2 % were high school dropouts, 5,1 % were high school graduates, 32,9 % had not completed college, 17,6 % had a bachelor's degree, 9,7 % had entered by not completed postgraduate education, and 34,5 % held a graduate degree or higher.

Instruments

An online questionnaire was administered including sociodemographic questions (gender, age, education), applied scales to assess hedonic shopping motivations, personality, and impulsive buying, and included six dichotomous questions about buying behaviors devised based on the theoretical definition of each dimension of the Hedonic Shopping Motivations scale. Respondents indicated, by answering yes or no, whether it was common to engage in certain purchasing behaviors. The questions about behaviors were the following: "Recently, I made purchases just for the excitement"; "In the last month, I have bought things just to relieve stress, forget about problems, and make me feel better"; "I remember how joyful I was when I recently bought a gift to show appreciation for someone"; "In the last month, I have made some purchases just to take advantage of discounts and promotions"; "Recently, I had the pleasure of spending time shopping with friends and/or family"; and "Recently, I bought a product just because it was a novelty." Control questions, mixed with the scale's items, were also asked, such as "This is only a control question. Please mark number five."

Hedonic Shopping Motivations Scale-Brazil (HSM-BR)

The Brazilian version of the instrument was adapted from Arnold and Reynolds (2003) in this study. The instrument consists of 18 items that measure hedonic motivations for purchases in six factors: Adventure, Gratification, Role, Social, Value, and Idea. The items should be answered on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 ("strongly disagree") to 7 ("strongly agree"). Evidence of validity, reliability indices, and other psychometric properties of this scale are presented in the Results section below. The adjusted indexes for the HSM-BR were CFI = 0,97, TO = 0,96, RMSEA = 0,045.

Reduced Scale of Descriptors of the five major Personality Factors (Red5;Natividade & Hutz, 2015)

This instrument measures personality characteristics from the perspective of the five major factors, containing 20 items, four for each factor. The items are in the form of adjectives or small expressions for the participants to answer on a 7-point scale to indicate the degree to which they agree to each item. In the present study, McDonald's Q and Cronbach's a for the factors were the following: Extraversion, Ω = .85 and a = .85; Agreeableness, Ω = .81 and α = .81; Conscientiousness, Ω = .72 and α = .72; Neuroticism, Ω = .73 and α = .72; Openness, Ω = .61 and α = .56. In the Natividade and Hutz (2015) study, the adjusted indexes were CFI = 0,97, TU = 0,95, RMSEA = 0,050.

Buying Impulsiveness Scale (BIS; Rook & Fisher, 1995; adapted for Brazilian Portuguese by Aquino, Natividade & Lins, 2020)

This scale proposes to measure a single factor regarding the tendency toward impulsive buying. The instrument contains nine items in the form of affirmative sentences. Participants answer the extent to which they agree with each statement on a 7-point scale. Higher scores indicate a higher level of impulsive buying. The present study found Mc-Donald's Ω = .87 and Cronbach's α = .87. In the Aquino et al. (2020) study, the adjusted indexes were CFI = 0,97, TLI = 0,96, RMSEA = 0,060.

Procedures

Translation

The original version ofthe HSM scale was translated from English to Brazilian Portuguese by four independent translators who were proficient in both English and Brazilian Portuguese. The translations were compared and synthesized by a fifth researcher in psychology and marketing with experience in adapting instruments. The researcher also compared the translations with the original English version. After this stage and minor editorial corrections, the research questionnaire became the final Brazilian version of the HSM scale (HSM-Brazil).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The project followed all standards for research with humans after approval from the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Neurology Deolindo Couto of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (INDC-UFRJ), an organization that is linked to Plataforma Brazil (protocol no. CAAE: 31253420.2.0000.5261). All procedures performed were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data Collection

Participants were recruited by e-mail and posts on social media networks. The invitations explained the survey and provided a link to access the questionnaire. On the first page of the questionnaire, a Free and Informed Consent form was available, complying with the ethical treatment and with all the guidelines, and regulatory standards for research with humans.

Results

The questionnaire was configured to disallow missing answers to the scale's items and contained control questions in various parts of the questionnaire to monitor the participants' responses (e.g., "This is only a control question. Please mark number five"). In order to eliminate any erroneous data, the responses to the control questions were subjected to a process of cleaning. This entailed the exclusion of all responses provided by participants who had answered incorrectly to a control question, resulting in the removal of the entire data set associated with these participants. We initially tested the instrument's structure using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). We used R software, the lavaan package, and the Maximum Likelihood Robust estimator in all CFAS and other structural equation analyses.

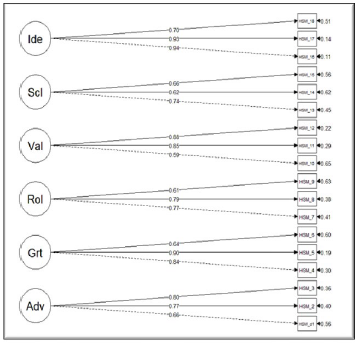

To test the structural adequacy of the instrument, CFAS were first performed. We tested adjustment of the data to the original model of the instrument, in which the items are explained by the six HSM factors that are correlated with each other (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003). The results were the following: ratio between X 2 and degrees of freedom (X 2 /df) = 1.140; Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0,97; Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0,96; Robust Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0,045 (90 % confidence interval [CI] = 0,035-0,055); Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) = 28477.3. The factorial loads of the items ranged from .59 to .94 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Standardized solution of the HSM-Brazil six-factor model. Ide = Idea Shopping; Scl = Social Shopping; Val = Value Shopping; Rol = Role Shopping; Grt = Gratification Shopping; Adv = Adventure Shopping. All factors were correlated between them.

Correlations between latent factors ranged from .31 between Role and Idea to .90 between Adventure and Gratification. Given these correlations, a general second-order factor model that explained hedonic motivations' six factors was tested. The results were the following: X 2 /df = 1,996; CFI = 0,96; TLI = 0,95; RMSEA = 0,051 (90 % CI = 0,0420,060); AIC = 28510.8. These results show data adjustment to the second-order model, but this model proved to be slightly less adjusted than the model with six correlated factors.

The calculated reliability coefficients (Cronbach's a and McDonald's Q) showed satisfactory internal consistency for each HSM dimension: Adventure, α = .79, Ω = .79; Gratification, α = .83, Ω = .84; Role, α = .74, Ω = .77; Value, α = .81, Ω = .82; Social, α = .71, Ω = .72; Idea, α = .89, Ω = .90.

To search for evidence of validity based on relationships with other variables, we tested correlations between HSM, Impulsive buying, and Big Five factors. Table 1 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients.

Table 1 Pearson Correlations between Hedonic Shopping Motivation and Other Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| HSM Adventurea | |||||||||||

| HSM Gratification1 | .74** | ||||||||||

| HSM Rolea | .37** | .30** | |||||||||

| HSM Valuea | .33** | .34** | .33** | ||||||||

| HSM Sociala | .47** | .43** | .36** | .36** | |||||||

| HSM Ideaa | .57** | .53** | .32** | .33** | .39** | ||||||

| Impulsive Buyinga | .36** | .42** | .04 | .09 | .21** | .32** | |||||

| Extraversionb | -.01 | .04 | .05 | .10* | .04 | .04 | .01 | ||||

| Agreeablenessb | .01 | -.01 | .07 | .06 | .12* | .02 | -.08 | .48** | |||

| Conscientiousnessb | .02 | .07 | .15** | .05 | .02 | .07 | -.27** | .09 | .16** | ||

| Neuroticismb | 19** | .21** | .10* | .15** | .05 | .09 | .24** | -.06 | -.26** | -.18** | |

| Opennessb | -.04 | -.01 | -.03 | .09 | .04 | -.03 | .01 | .29** | .21** | .06 | -.07 |

Note. HSM = Hedonic Shopping Motivations. a: n = 429, b: n = 329.

*p < .05

**p < .01

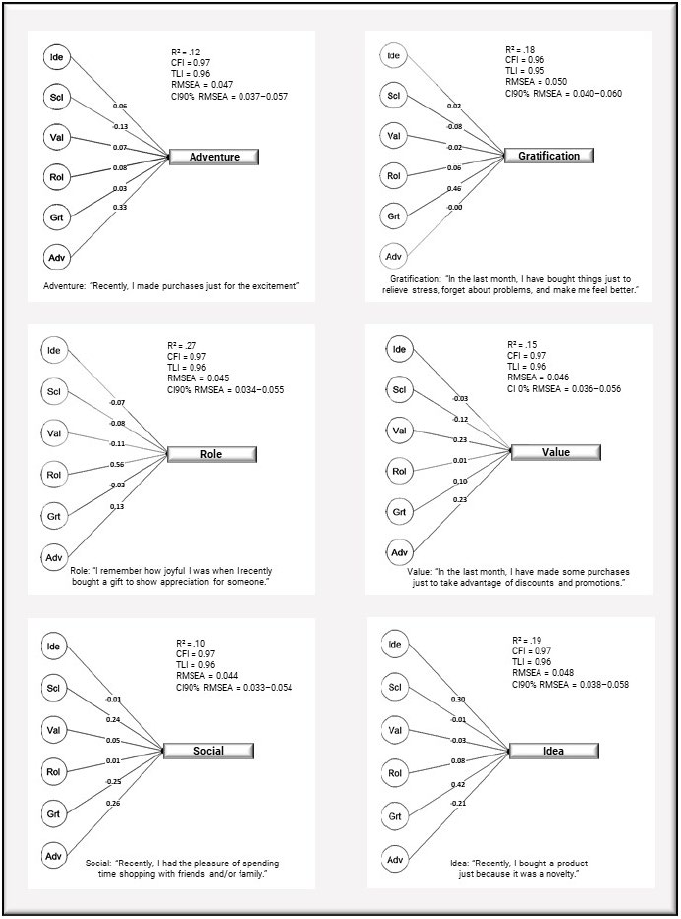

Next, we tested whether hedonic motivations could explain specific behaviors (e.g., "I recently bought a product just because it was new"). To this end, we used six questions about behaviors that were performed recently and configured six models in which the factors of hedonic motivations explained the behaviors. Figure 2 shows the tested models.

Figure 2 Hedonic Shopping Motivations predicting behavioral variables. Ide = Idea Shopping; Scl = Social Shopping; Val = Value Shopping; Rol = Role Shopping; Grt = Gratification Shopping; Adv = Adventure Shopping. N = 429.

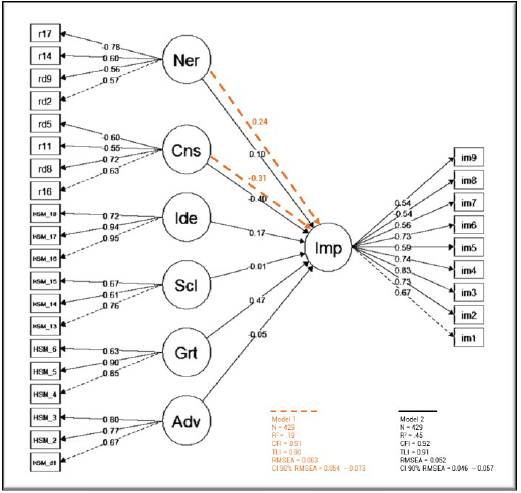

Finally, we tested whether hedonic motivations could predict impulsive buying and add explained variance beyond the Big Five. For that purpose, we ran the analyses with Big Five and HSM factors that showed correlations with impulsive buying. The Neuroticism and Conscientiousness factors explained 19,3 % of the variance in impulsive buying. When the HSM Idea, Social, Gratification, and Adventure factors were added to the model, the explained variance was 45,2 %. These results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Model 1: Personality factors predicting impulsive buying. Model 2: Personality factors and Hedonic Shopping Motivations predicting impulsive buying. Ner = Neuroticism; Cns = Conscientousness; Ide = Idea Shopping; Scl = Social Shopping; Grt = Gratification Shopping; Adv = Adventure Shopping; Imp = Impulsive Buying.

Discussion

The present study provided evidence of validity for the Brazilian version of the HSM scale. We found that the data adequately adjusted to the structure of six correlated factors of the instrument, consistent with the original study by Arnold and Reynolds (2003). Although the six-factor model had the best adjustment indices, we found that a model with one second-order factor and six first-order factors also had satisfactory adjustment indices. This suggests the possibility of computing a single score for the HSM scale. Additionally, the reliability coefficients indicated satisfactory internal consistency for factors, aligning with the original version of the instrument (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003).

To search for evidence of validity based on relationships with other variables, we tested relationships and explanatory models of the motivations with the Big Five personality factors, impulsive buying, and buying behaviors. Therefore, the present study presents results of the network of associations among hedonic motivations, individual trends (personality and impulsive buying), and purchasing behavior itself (even if evaluated retrospectively and through self-report). Such a network of associations (i.e., a nomological network) also serves as a source of validity evidence for the presently adapted instrument and a source of data for theoretical formulations on consumer behavior.

The weak correlations that were found between hedonic motivations and the Big Five personality factors suggest that the psychological roots of hedonic buying motivations are not explained by the Big Five. Future studies can investigate which individual and contextual characteristics contribute to explaining hedonic motivations. For example, one can investigate the role of affect, the time of exposure to the product inside the store, or even seasonal stimuli in hedonic motivations (e.g., Aquino et al., 2021).

We found positive correlations among four factors of the HSM scale and the tendency to buy impulsively. Adventure and Gratification were the HSM factors that were most strongly correlated with impulsive buying. Higher susceptibility to making purchases when absorbed by the idea of immediate gratification, which is typical of impulsive buying, is associated with higher motivations that refer to an individual's intrinsic longings, such as self-care and the search for stimulation. This result corroborates the idea that sensory stimulation is widely associated with impulsive buying (Aquino et al., 2020; Blut et al., 2018; Beatty & Ferrell, 1998; Coelho et al., 2023; Hashmi et al., 2020; Hirschman & Holbrook, 1982; Erdem & Yilmaz, 2021; Rook & Fisher, 1995).

Two other HSM factors that correlated with impulsive buying were Idea Shopping and Social Shopping. Idea Shopping, one factor related to external stimuli, such as the offer of products considered novelties for the general public, can explain why impulsive buying is directly linked to product attractiveness (Iyer et al., 2020; Rook & Fisher, 1995). As the tendency toward impulsive buying increases, stimulated by the desired product's physical proximity, the motivation to be informed and to learn everything about recent updates is also enhanced (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Guido et al., 2007). Social Shopping was the HSM factor that had the lowest correlation with impulsive buying. Social Shopping is linked to social interactions while shopping, and its significant correlation with impulsive buying, albeit low, can occur because social influence or the mere presence of other people at the time of purchase can affect impulsivity shopping tendency as found before (Aquino et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2013; Luo, 2005; Neto et al., 2022). The current literature indicates a relationship between shopping with other people and an inclination to make impulse purchases. However, there is no consensus on this topic, as the results of studies do not always indicate this direction (Erdem & Yilmaz, 2021).

Furthermore, we tested whether HSM factors would predict impulsive buying. Previous studies demonstrated the predictive power of the Big Five factors for impulsive buying (e.g., Aquino et al., 2019; Bratko et al., 2013; Olsen et al., 2015; Thompson & Prendergast, 2015). Therefore, we tested whether the HSM scale would add explanatory power to impulsive buying, apart from the five major factors. Although 19 % of the variance in impulsive buying was explained by personality factors, the explanatory power of the tendency to buy impulsively reached 45 % in the scope of hedonic dimensions. For example, the Gratification Shopping factor had the highest explanatory power, even greater than the Consciousness factor. These findings open the possibility of interpreting impulsive buying as a self-care mechanism when an individual engages in purchases to provide specific pleasure for oneself.

Arnold and Reynolds (2003) theorized that buyers may not easily acknowledge their reasons for buying or may not consider many things when thinking about the reasons why they go shopping. Nonetheless, hedonic motivations also proved to be predictors of specific purchasing behaviors. For example, the memory of feeling happy when buying a gift to show esteem for someone was strongly predicted by the Role Shopping factor. This factor reflects the inherent pleasure and joy of shopping for others and the satisfaction that is gained from fulfilling social roles when shopping. Idea Shopping, the definition of which includes a continuous search for recent trend updates, strongly predicts the avowed behavior of buying a product just because it is new. Knowing that purchasing behaviors can be influenced by perceptions of money or the importance of possessions (Denegri, 2022), it is interesting to find that Value Shopping was a predictor of the act of buying only to take advantage of discounts and promotions. Additionally, this engagement of individuals in "bargain hunting" behaviors was also predicted by the Adventure Shopping dimension. The personal fulfillment that is found in the act of bargaining and the pleasure of bargaining are also behaviors that are linked to the search for sensory stimuli and elation at the time of shopping.

Adventure Shopping proved to be a strong predictor of buying something solely for the excitement, which was theoretically expected, whereas the Gratification Shopping dimension predicted the behavior of buying things to relieve stress, forget about problems, and become a little excited. However, both dimensions also predicted behaviors that are already predicted by other factors, such as Social Shopping and Idea Shopping. The quest for adventure and gratification also impacts the pleasure of finding gifts for someone and the search for new things. Adventure and Gratification are factors that refer to the individual's intrinsic longings for self-care and search for stimulation, and this can instigate people to use shopping as a distraction or for fun, zeal, and attention oriented toward themselves. Notably, they are also strongly predicted behaviors that somewhat satisfy social needs (i.e., Role Shopping factor) and a reaction to external stimuli to achieve pleasure by the acquisition for their favorite shopping products (i.e., Idea Shopping factor). Thus, hedonic motivations could be considered utilitarian because they are helpful for fulfilling practical functions in people's lives.

One limitation of the present study was that the participants' mood or affect was not tested, and such variables can influence accurate interpretations of the topic (e.g., Ozer & Gultekin, 2015). Another limitation was the highly educated sample, which was concentrated in Brazil's wealthiest regions and likely biased the answers when considering the participants' rather uniform financial profiles. Nevertheless, non-probabilistic random convenience sampling provided a wide and varied age diversity that was not limited to university students, which helped reveal a trend in behavior among general consumers, without linking such trends to specific profiles (Cardoso & Pinto, 2010).

In addition to demonstrating the adequacy of the HSM scale to the Brazilian context, the present results provide evidence that some individuals buy to achieve satisfaction with the shopping experience itself and do not necessarily only see a shopping trip as the mere execution of a task (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Kaltcheva & Weitz, 2006). If other factors drive an individual's he-donic "just do it" attitude, then the challenge to determine which predictive forces drive hedonic purchase motivations remains. Future research could investigate the history of buying behaviors and motivations, such as exposure to persuasive communications, susceptibility to social influence, and other dispositional characteristics.