1. Introduction

Banerjee and Duflo consider that the problem of poverty has given rise to a series of political positions that reduce the public debate to simple formulas in which very little account is taken of the poor as a source of knowledge. The everyday behaviors and decisions of individuals turn out to be of little interest to these economic perspectives, which, in the end, affect the bid to end poverty.

The approaches that focus on the free market as a factor favoring opportunities, or those that emphasize the role of human rights in strengthening capabilities, or the need not to lose sight of social conflict in the analysis of causes, to those that consider it imperative to increase transfers to address the vulnerability, and the significance of international development aid, has made significant contributions to understanding the problem, but what the authors suggest is that we should not lose sight of how the poor life, which implies intense fieldwork focused on the experiences of the subjects.

Duflo and Banerjee are two economists from France and India, respectively, who have served as research professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and are co-founders and co-directors of the J-PAL Poverty Action Lab (Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab) founded in 2003 and currently composed of 750 researchers, which is dedicated to evaluating the effectiveness of public policies for poverty reduction1.

Through donations, they have managed to carry out more than 1600 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in more than 80 countries; in addition, the verification of programs through this methodology has allowed the expansion of public policies that have benefited 600 million people around the planet (J-PAL, 2023). This hard work has earned them many recognitions, the most important being undoubtedly the Nobel Prize in Economics received by Banerjee, Duflo, and Michael Kremer in 2019 for their methodological contributions to development economics that is concerned with providing reliable results from small-scale analysis (THE ROYAL SWEDISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, 2019) (Adriano, 2020).

As is well known, experimental studies have an outstanding trajectory in research in the field of health; in some areas of the social and human sciences, it has also made a career, specifically in psychology and political science (Casas and Méndez, 2013). In the economic discipline, the first experiments date back to the 1930s and 1940s (Fatás and Roig, 2004) (Brañas and Paz Espinosa, 2011); however, their application to measure the effect of poverty intervention policies is relatively recent.

It is in this area that the authors' invitation is focused, not to lose sight of the details, basically for two reasons: first, because for those responsible for public policy, it is not always a priority, and when they must face them they do so based on speculation, without much regard for the evidence. Second, those details that are considered unimportant may turn out to be extraordinarily significant in determining the ultimate effect of a policy, while some first-order theoretical issues may not be as relevant (Duflo, 2017). In this way, they have been able to understand how large investments end up failing for reasons or attitudes that, in principle, have no apparent logic or rationality.

Thus, Esther Duflo asked in 2003, "How has a given program in a developing country influenced the poor whom it is supposed to benefit" (Caminis, 2003, p. 4). Moreover, Banerjee, referring to international cooperation aid, added "much of this money is being misspent, guided by ideologies or political beliefs, but with little faith in science" (Aunión, 2009). Therefore, they recommend that economics should not start from global questions (What is the main cause of poverty? To what extent should we believe in the free market? Is democracy good for the poor?) but determine specific problems that affect the subjects, and examine the most appropriate mechanisms to intervene (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021).

In this sense, the fundamental question of this pair of researchers is based on the recognition of the role of economics as a discipline in the formulation of policies for the resolution of social problems, so they consider it necessary that the epistemological contributions to public management do not remain in analytical models but understand the complex world of details and circumstances of social intervention, that is, intellectually face the uncertainty of the processes to define much more effective and efficient tools and actions (Duflo, 2021).

But how does this proposal differ from others that have existed for the same purpose? In these twenty years, the work of the laboratory (J-PAL) has had an important influence on policy in a way that is different from other processes; Duflo points out that these basically consisted of a set of advisories by experts who, with a certain regularity went from one place to another offering macroeconomic advice in coherence with an economic theory or the intuitive notions they had. He also mentions that it differs from the influence exerted by the so-called "Chicago Boys" who advised Pinochet's Chile in the 1970s.

The J-PAL perspective is less concerned with global theses and focuses much more on specific suggestions. It is here that they make a strong critique of Jeffrey Sachs and William Easterly, who have staged a debate around the importance of cooperation vis-à-vis the fight against poverty in developing countries. "We take seriously both the guiding principles and the less glamorous, but still crucial, realities of day-to-day policy implementation." Thus, when engaging in public policy design anywhere in the world, one must "take responsibility for getting the big picture and the broad design right" (Duflo, 2020, p. 1953). Thus, the laboratory researchers are aware that the proposed strategies could be implemented in various parts of the world, so they must be responsible for the specific aspects that may arise and that the models or theories constructed have not been addressed in a timely manner.

In this sense, this article reflects on some of the academic contributions made by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo to the understanding of poverty. To this end, the analysis is focused on the works Rethinking Poverty. A radical turn in the fight against global inequality (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021) and Fighting poverty. Experimental tools to confront it (Duflo, 2021) and other articles where specify, define, and expand their research concerns. From a qualitative approach with interpretative scope, hermeneutics was applied, where the text serves as a tool for observing the social phenomenon (Naranjo, 2020).

For this purpose, this paper was divided into three sections: the first part presents a general presentation of the methodological notions of randomized controlled studies, the second part presents the discussion on human development as a public policy approach to health care and education, and the third part deals with the policy of autonomy, which includes contributions on the role of microfinance in the generation of individual capabilities. It is expected to contribute to the understanding of a complex social phenomenon of high importance in the public and academic debate.

2. Experimental methodology, in general

To experiment is to intentionally place the object of study in certain conditions in order to observe its behavior. This implies modifying the natural environment or creating an artificial environment for the purpose of recording the changes, permanence, and fluctuations that are provoked. For these dynamics of the object to become evident, it is necessary to the existence of a control group, which is the group of the sample that does not see its conditions affected or receives a differential treatment, becoming a point of reference when assessing the effect of a certain action on the experimental group, who are directly involved in the core of the research intervention.

These two population sets must have similar aspects that allow their comparison in order to make the respective inferences; thus, the selection of individuals is a fundamental part of the design; of course, the externalities of the process must be made aware since it is not possible to have absolute control of all the factors. It is not superfluous to indicate that, prior to the experiment, a diagnosis should have been carried out in order to be clear about the initial characteristics of the subject (the so-called baseline of the object problem) (Hernández Sampieri and Mendoza Torres, 2018) (Ñaupas, Valdivia, Palacios, and Romero, 2018).

In the social sciences, of course, this process is not a simple exercise, mainly if the experiments are carried out in the field (Cárdena, 2013) (Vélez, Moros, and Bermúdez, 2013). Paul Samuelson, Nobel Prize in Economics (1970), asserted that because social behavior is very complex, it was not possible to achieve the precision of other disciplinary research, and he dared to sentence: "nor perform the controlled experiments of the chemist or the biologist; we must be content with «observing», much as the astronomer does"; but even observation is limited because events and economic data do not behave as orderly as the trajectories of the planets (Samuelson, 1975).

Thirty years later, other economics nobels were still recognizing the absence of a great universal answer, but with the difference that there were higher quality data and a powerful instrument, the randomized controlled trials (RCT), precisely to carry out "large-scale experiments in which researchers, working with a local partner, test their theories" (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021). The itinerary of this methodology was not linear and owed much to Psychology, Political Science (Casas, 2013), and pioneers such as Vernon Smith, another Nobel laureate (2002), who was the one who finally catapulted this type of research in the economic field in the 21st century (Smith, 2005) (Talavera Aldana, 2003).

Nevertheless, how does one conduct an experiment in the social sciences? Without being exhaustive, experts recommend some basic issues: a concrete problem, a straightforward design, and having the greatest control over contingencies and incentives (Brañas and Barreda, 2011). This means that the selected individuals must face a situation (e.g., taking their children to vaccination, going to work) that has to be described in detail in the framework of the project (the whole planned exercise), which is intended to ensure that accidents or risks have the minor effect on the experiment (unobservable variables that may interfere) (García, 2008), and, finally, it is necessary to offer stimuli that provoke the behavior (a subsidy, a pound of lentils).

In this sense, what should guarantee the researcher a well-conducted experiment is that it is possible to "observe the decision-making process in a controlled environment, ensuring that the variations are the product of the experimental conditions intentionally promoted by the researcher, and not of external circumstances" (Méndez, 2013, pp. 28-29). In short, in order for the results to be generalizable, it is imperative to control the conditions and randomization. The former involves defining the baseline that will be useful for recognizing changes and permanence, and the latter refers to the mode of selection of the sample members to ensure neutrality.

A couple of examples may help to clarify these characteristics and resolve certain doubts. Duflo and Banerjee have worked with the NGO Seva Mandir, an organization with more than 50 years of experience based in Udaipur, India. Among the many problems they identified in this population was that the proportion of children with complete basic immunization was less than 5% of the total. There is agreement among the scientific community that these have the capacity to save lives since around three million people die annually from diseases preventable with this immunization scheme.

However, these data were not enough for the citizens, and the fact that it was free of charge did not seem to be a sufficient attraction. What was going on, and why was this behavior occurring? Early impressions focused attention on the absenteeism of nurses at health centers, for which it was common to blame them. In 2003, Seva Mandir launched its own vaccination campaign with systematic outreach. Although they succeeded in getting an average of 77% of children in the campaign sites to receive at least one injection, the difficulty was in completing the process.

That is, despite the fact that the action was private, free, and domiciliary, "8 out of 10 children were left without full vaccination" (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021, p. 83).

Among the many hypotheses that were considered, they decided to experimentally explore people's beliefs. Contrary to what one might think, the poor are very concerned about health and are able to spend large amounts of money, both on medical treatments and on culture-specific interventions (healers, sorcerers, and preachers) (Banerjee and Duflo, 2007). However, their concerns will be more intense if it is about a present condition, while if it is about preventing future disease, there is a relaxation in attitudes; individuals allow themselves to postpone some decisions.

This added to the deficiencies of the public health service, the ideological notion that defines <<free as useless>>, and the traditional beliefs in relation to diseases, creating a more complex problematic knot. Is it possible to undo it? How long would it take to see the first signs of behavioral change? Moreover, of course, surely it must be a very costly process. A pilot program implemented by J-PAL and Seva Mandir may offer some preliminary answers. Let us see what it is all about.

Banerjee and Duflo were able to convince the NGO delegate in Udaipur to offer a kilo of dal (dried beans, a staple food in Udaipur) to people for each vaccination they received and a stainless steel dinner service for anyone who completed the treatment. There was much skepticism among the medical staff in charge of leading the program, but in the end, they did it. What could be the relationship between a commonly used, otherwise inexpensive food and vaccination? It didn't seem to be much of an encouragement to the population, but that's exactly what Duflo and Banerjee wanted to test: beliefs were strong enough that they wouldn't succumb to such a basic gift. The results were surprising: where they focused the campaigns, vaccination rates rose from 6% to 38% and even increased in the surrounding villages due to the spontaneous circulation of information.

What this meant in terms of preventing deaths was that those responsible set out to replicate the exercise in other settings. However, among medical staff, these effects were not met with the same astonishment, as they noted that "38% was far from the 80% and 90% required to achieve herd immunity" (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021, p. 91). This, of course, the researchers knew, but they considered that the "all or nothing" argument was not really sensible, for protecting one child at least protected those around him or her, which was a relevant social benefit. However, an aspect that should also be emphasized as an epistemological resource is that some beliefs of the poor do not always constitute a firm conviction, so there may be simple strategies that, like a drop of water, end up breaking the hardness of a traditional notion that hinders the resolution of a social problem.

Another example concerning education in the same city refers to teacher absenteeism in rural schools, which represented 44% of working time. Since public incentives that rewarded teachers based on students' academic results did not work, a less orthodox strategy was chosen. Seva Mandir distributed cameras to record work with students twice a day. Participants in the experiment were to receive "a bonus for each additional day of presence" in addition to their fixed salary. This program quickly generated important changes in faculty behavior: in the institutions where it was implemented, the absenteeism rate dropped by half (from 44% to 22%) and was maintained not only during the process but even when it ended, so the NGO adopted the experiment as a permanent strategy (Duflo, 2021) (Duflo and Hanna, 2005).

It may not work in all contexts, however; Duflo notes that a similar gamble was applied in Kenya and proved a total failure. Instead of cameras, teachers offered bicycles to reward regular attendance under the supervision of the school principal. Although internal evaluations indicated total success (all received bicycles), random external monitoring showed that absenteeism continued. Part of the explanation is related to a certain complicity between the staff and the school administration, as opposed to the NGO that was committed to the experiment. However, the author points out that it is possible to motivate teachers; it is only necessary to build strategies that allow focusing on a concrete cause for action in which all the actors involved are committed (Duflo and Hanna, 2005).

This is the epistemological richness provided by RCTs; they help to reveal hidden or at least not-so-visible aspects of the usual theoretical models, contributing not only to the understanding of some failures but also to the formation of alternative solutions. Of course, it would be wrong to think that an experimental exercise is enough to reach general conclusions and evaluate the social impact of a program. "Each experiment is like a dot in a pointillist painting: by itself, it does not mean much, but the accumulation of experimental results ends up drawing a picture that helps to understand the world and to guide policies" (Duflo, 2020, p. 1955).

It should be remembered that RCTs are data collection instruments, so in order to obtain a volume of information, they must be applied according to the parameters, the problem, and the objectives of the research or intervention. Therefore, Duflo invites the economist's work to be more similar to that of the "plumber" and less like that of bureaucrats or civil servants2, since in this way, one could be more attentive to the details of the circumstances surrounding the social problems on which one seeks to have an impact (Duflo, 2017). Consequently, the authors, in their analyses, do not lose sight of the general and the particular (even the singular) of the facts; their reflections have a movement that allows them to intellectually attend to the conditioning factors (social, cultural, economic, political and institutional) and the subjectivities of the poor.

3. Human development: the expansion of capabilities

Adam Smith (1776), in his work Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, pointed out that "no society can be flourishing and happy if the greater part of its members are poor and miserable" (Smith, 2017, p. 77) with which he indexed a moral purpose to the economic process for the general welfare. This idea was already found in Aristotle, when he pointed out wealth as an instrument for the achievement of other purposes, in Kant, with his categorical imperative, and in the precursors of the economic discipline (UNDP, 1990).

However, it was on December 4, 1986, that the United Nations General Assembly approved the Declaration on the Right to Development, which established it as an inalienable human quality and equal opportunities as a prerogative of citizens and countries. In this sense, promoting development implies attending institutionally in a holistic manner to "the application, promotion, and protection of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights," whereby development policy turns the human being into a participant and beneficiary of the process "3.

However, the hegemonic political discourse continued to conceive development in terms of major structural processes, such as the growth of gross domestic product (GDP), industrialization, technological progress, etc., where the human condition and quality of life remained on the periphery of the models, but some had already been indicating their disagreement with this position. Since the 1970s, new visions have emerged, with some elements in common and others contrasting, namely the welfare economy approach, liberal egalitarianism, capabilities, and basic needs.

The first, rooted in Bentham's utilitarianism, defined the individual as sovereign in the definition of his interests so that needs were equated with preferences. The second is a major source in the work of John Rawls, who superimposed the just over the good "and took up the treatment of the so-called distributive justice." The third is directly related to Amartya Sen, who recognizes that "freedom and rights have intrinsic importance in people's lives" and, finally, the needs approach that cannot be attributed to a particular author since there is plurality in the conception of needs (subjective or objective) even though there is consensus regarding their universal character, as certain "serious harms" that may affect people's moral and agency capacities are thus noticed (Di Pasquale, 2021).

These trends are essentially distinguished in the way they perceive welfare; there is the one that reproduces the notion of the individual as an instrument of the production system (welfare economy), the one that understands the citizen as a beneficiary of redistribution policies (liberal egalitarianism), and, finally, those that focus on the generation of opportunities and provisioning of goods and services that poor population groups lack (capabilities and basic needs approach) (Correa, 2020).

Thus, poverty gradually ceased to be understood as a strictly monetary issue, although this aspect is still in force as a methodological indicator for indirect measurements. In this context, Amartya Sen, economist and philosopher, contributed to emphasizing the role of income in the analysis of needs and moving towards a multidimensional vision. At the end of the 20th century, he proposed that development should be understood as "a process of expanding the real freedoms enjoyed by individuals." Therefore, he conceived poverty fundamentally as a deprivation of capabilities, thus specifying three basic principles: one, attention should be focused on what is intrinsically essential instead of only what is instrumentally important; two, it should be clear that there are other sources that affect the expansion of capabilities; and three, it should be understood that the effect of the income factor on freedoms is heterogeneous (Sen, 2000).

Capabilities, in turn, are related to the agency of the individual, that set of faculties and conditions that allow for influence in the affairs of the world and of the person himself. Every subject must have the possibility of interacting in the market mechanism and in the social field, without arbitrary restrictions, to achieve what he would like to achieve, be they material, symbolic, political, cultural, or social objectives (Sen, 2000). In short, human development, which results from the combination of the basic needs and capabilities approaches, seeks not only to satisfy basic needs but also to generate "a dynamic process of participation"; the idea is to arrive at the best alternatives of what one should have, be and do for one's own subsistence (UNDP, 1990).

The human development approach is now recognized in the economic field and multilateral institutions. For example, of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) signed by 193 countries in 2015 (the 2030 agenda), two are directly related to health and education (SDG 3 and SDG 4), and two others are related (SDG 2 Zero Hunger and SDG 6 Clean Water and Sanitation), each in turn has a particular set of indicators for their concrete assessment. Duflo and Banerjee, precisely, continue this line of reflection to show the importance of education and health as crucial factors in the development of human potential, becoming an intermediate perspective between those skeptical of aid to the poor and those optimistic about its effectiveness in combating poverty. The development of capabilities," he argues, following Sen, "cannot be left entirely to the initiative of those whose freedom is restricted by obstacles of all kinds" (Duflo, 2021, p. 46).

For example, a person who has grown up in the midst of material precariousness, whose physical and mental efforts are focused on the resolution of daily needs, who suffers from time to time some crisis due to the flexibility or informality of the labor market in which he is integrated, or the environmental vulnerability of his home, with little or no academic training, among many other characteristics that act socially in an intersectional way, is likely to make him feel in a kind of labyrinth that is very difficult to get out of, blocking him emotionally and mentally. In this way, the pair of researchers recognize the weight of structures in the experiences of individuals, but with the difference that they believe that intervention mechanisms or strategies can be designed to allow people to escape the traps of poverty.

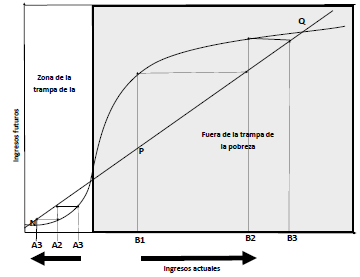

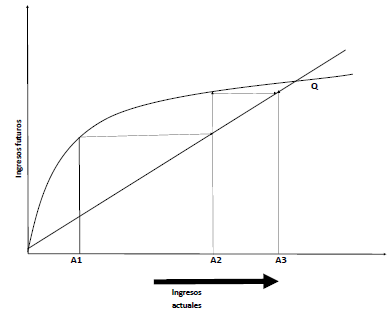

What is a poverty trap? In general terms, it is considered to be a structural situation that perpetuates multidimensional precarious conditions in countries, population groups, families, and/or individuals. For such a phenomenon to occur, a series of factors must converge to limit the growth of income or wealth in those who have very little to invest but not in those who have the capacity to invest much more (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021). Based on the macroeconomic assumption that the current income level of individuals or families can influence and project future income, two graphs are presented that allow us to observe possible scenarios of social mobility.

On the one hand, as shown in Figure 1, the S-shaped curve exhibits the poverty trap, which suggests that the poorest people, i.e., those with the lowest current income, are located at the beginning of the curve below the diagonal Q, which places them in the poverty trap area; this would mean that their future income will tend to decrease shifting to the left, with a possible path from Al towards A2, then decreasing towards A3 and so on, making it impossible to get out of the poverty trap. Under this assumption, as time passes, the poor become poorer.

In this sense, in Figure 1, those outside the poverty trap area would have a trend increase in future income as they move from Bl to B2, then to B3, and so on until income reaches a constant point.

On the other hand, in Figure 2, the L-shaped curve shows the assumption that there is no poverty trap; the curve grows faster at the beginning and then at a slower rate; according to this view, the income of the poorest always exceeds the income with which they started until income stops growing to be constant. In this scenario, the trajectory from Al to A2 and then to A3 reveals that people increase initial wealth; however, even if income increases, the curve points out that in the end, they always head to the same destination; thus an increase in income due to some subsidy or support would only mean accelerating the trajectory, but the final destination would be the same (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021).

For the authors, neither scenario is entirely applicable to reality (theory is not enough). According to their vision, each case would imply different factors that would influence the analysis of social mobility in a different way. Although there are structural elements that limit people's actions, human capital and the different ways of coping with poverty are more complex than the graphic models just described; an important point to consider would be the way in which societies distribute their wealth. Therefore, it is not a matter of evaluating each modality in which people are trapped, "but rather the few key factors that generate the traps," in order to then design effective intervention strategies to solve the specific difficulties that would rescue the poor, channeling them onto the virtuous path of economic prosperity (growth of wealth and investment) (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021).

It is not strictly speaking a middle ground between the positions that privilege supply or demand, but a critical point, since from the latter they rescue the need to take into account the needs of the poor, and from the former the moral obligation to help others. The invitation is to act on the basis of a set of specific knowledge and to take into account all the results that this action triggers. In this sense, the authors experimentally review some ideas or theses that are commonly repeated in the political and academic jargon related to education and health.

Why do schools fail? Does top-down education policy work? Have private schools solved the quality problem? Do expectations ultimately have a negative effect? These are some of the questions that the pair of economists ask themselves in the specific case of the educational field. It is not the intention to give a punctual answer to each of them, as there would not be space in this exercise. But in order to give an account of the arguments of the approach, we could point out the nuances they propose in the supply and demand debate, that is, whether the state should act for the benefit of the needy population (offering social services) or whether it is better to respect people's decisions regarding their circumstances (if they do not do so, it is because it is not in their interest).

The difficulty they find with respect to the latter position is that it is not about access to luxury goods but issues that are considered central to a dignified life, such as drinking water, academic training, vaccines, etc., so that the rational perspective would have its limits. With respect to the others, due to their conviction of the imperative of intervention, they lose sight of the details of the problems and seem to be satisfied with certain global indicators. Therefore, the debate is "whether governments should intervene and whether they know how to do so" (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021, p. 103) (Muñetón and Gutiérrez, 2017).

It is clear that public management today suffers from a bad reputation in terms of effective or positive results; the problems of corruption and the heaviness of the administration in the execution of actions sustain this reputation. However, the public sector is, in reality, the power with the greatest capacity to generate long-, medium--, and short-term changes in multiple areas (Mazzucato, 2022). In the social sphere, some of its practices have become a point of reference (Lindert, 2011).

One of these remarkable experiences is represented by the "Progresa" program that inaugurated conditional cash transfers (CCTs) in the world. Implemented in Mexico by economist Santiago Levy, it consisted of offering "money to poor families, but only if their children went to school regularly and if the family sought preventive health services" (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021, p. 110). Because of its good results, this redistribution mechanism was applied in a variety of countries in the East, Latin America, and even in cities in the USA (Rezzoagli, 2017).

However, some studies tested conditionality to observe its determinant character in the behavior of families and surprisingly found that it was not so significant since "the effects were the same for those who received the conditional transfer and for those who received it in an unconditional form" (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021, p. 111).

On the other hand, the privatization of education, which could represent the demand sector, was a phenomenon that became widespread in the 1980s and 1990s as a way of avoiding dependence on public education, which was considered to be of low quality. Although students seemed to learn more in those institutions, there is not enough data to evaluate its effect. But that has not mitigated the ideological voices calling for the privatization of everything. Nevertheless, the authors find that they are not as efficient as they proclaim, since in an exercise comparing the instructional effectiveness of a Pratham program (a very important NGO dedicated to teaching) with private schools and public, they found that the results were more significant in the former, despite the fact that the collaborator (balsakhi, friends of the children) had only received a one-week training and had a much lower level of training than the teachers in the schools (Banerjee and Duflo, 2021).

Therefore, for Duflo, it is necessary to form a set of best practices based on the comparison of the effects of implemented projects. Otherwise, anyone can justify his idea or miraculous solution and resign himself to some results (Duflo, 2008). It is the accumulation of evaluated experiences that gives meaning and justifies the whole enterprise. Ultimately, it is an epistemological and methodological call for the construction of inclusive public policies and not the application of proposals based on hegemonic ideological notions.

4. The policy of autonomy

Do the poor have the capacity to generate tools and actions that allow them to get out of poverty traps? How successful are policies aimed at the poor that seek to encourage economic development through fiduciary or women's empowerment? Various studies by Duflo and Banerjee shed some light on these questions, the basis of which seems to be a reflection from different perspectives, including anthropological, sociological, psychological and, of course, from the perspective of decision-making under the rationality of homus economicus.

Through a series of experiences and social experiments that are reflected below, the Nobel laureates have challenged some classic theories that assumed that with a little "help," the poor could self-generate better employment conditions and thus improve household welfare. However, as is often the case in the social field, there are several factors involved in individual and family decision-making. This allows us to understand the poor not as mythical beings who may be villains or heroes of stories or stories of sorrow or success but as complex individuals with desires and wishes and with different ways of reacting, even within the family nucleus in which negotiation seems to play a fundamental role in deciding the household's economic policy (Pande, 2008).

The first experiment that examines this issue is the joint study by Duflo, Banerjee, Glennerster, and Kinnan (2013), conducted in Hyderabad, India, to randomly assess the impacts of microcredit in new markets. This analysis begins with the premise of a significant increase in the number of poor households that have applied for some form of microcredit, which grew considerably from 1997 to 2010. Although, from the most optimistic theory, it was seen as a profitable and altruistic business to grant loans to poor people (under the conception that this tool would represent an incentive against poverty), in practice, the results were not as optimistic as it has been proven in different countries, even in those considered as developed; an example of this is what happened in 2010 in the United States of America, where a wave of suicides related to over-indebtedness with microfinance institutions was reported. It is from the scarcity of statistical data that the authors seek to explain the effect or effects that microcredits could have on poor households.

The proposal by Duflo et al. (2013) is an ideal experiment to study access to microcredit in a randomized manner, assigning it to some areas (experimental group) and not to others (control group); the objective was to compare the result between the two, it was a more complete test and of greater scope by analyzing households in the medium term (households were followed for three and a half years after the introduction of the program).

The study was initiated in 2005 in 42 of the 104 neighborhoods of Hyderabad; these neighborhoods were randomly selected (randomization) to participate in the opening of a new microcredit branch called Spandana. In this first analysis, 6,850 households were surveyed; at the same time, other microfinance institutions also offered programs in the selected and other areas. It should be noted that, from the beginning of the program, the potential recipients of credit were groups considered to be poor but not the poorest. The areas in which the trial was applied were urbanized areas with services such as water and electricity; in addition, the families were expected to have their final residence in permanent settlements, that is, to prove the tenure of their homes, in any case, the logic of the microcredit is to guarantee the payment of the loan to the capital with the respective interest.

Some of the first significant findings were that in households that could be followed up, the loans were larger and had been borrowed for longer periods of time. Secondly, because the study model considered several variables of analysis, it was possible to observe that households that had access to microcredit tended to sacrifice short or even medium-term consumption in favor of durable goods4 or investment in a new or pre-existing business. This means a change in decisionmaking in the family nucleus, as well as better rationalized actions. Households reported a decrease in spending on festivals and on what they define as "temptation goods" (alcohol, tobacco, betel leaves, gambling, and food consumed outside the home). Another effect is the increase in the supply of labor; since the microcredit was taken, families have tended to seek extra income to repay the loan. An advantage of the economic model developed by the authors is the predictability of the debt cycles; according to the data, the second cycle of indebtedness can be like the first if there are durable goods to be acquired.

However, an effect contrary to what might be expected was that the microcredits did not make the average enterprise more profitable. According to the study, the tendency is that larger enterprises are the ones that show growth in profits, and no improvement effects were found in other social variables such as women's empowerment or health. In the context of these results, the authors emphasize that microcredit is not applicable to all households and note that it does not trigger the fundamental social transformation that many have advocated. Instead, they found that the main effects took place in the way of defining spending, prioritizing durable goods, or the stability of the family business without implying a leap that would make it possible to fundamentally modify the dynamics of social deprivation (Duflo et al., 2013).

Another experiment that can be related to the premise of the effect of microcredit as a policy of autonomy in the fight against poverty is the study conducted by Crepón, Devoto, Duflo, and Parienté (2011); in this work, the authors analyzed the effect of microcredit in rural areas of Morocco through a randomized experiment. The analysis studied the expansion of a microfinance institution called Al Amana, surveying 4,495 households in total.

In principle, it should be noted that microfinance institutions have been successful in expanding their financial services to sectors of the population marginalized by the conventional financial system. Sometimes, the discourse of supporters of microcredit policy is based on the belief that microfinance can alleviate poverty, create self-employment, promote gender equality, empower women, and improve children's education. On the other hand, those who criticize the microcredit policy argue that it can lead to indebtedness and that, in the end, this mechanism does not solve the problem of poverty. Faced with this dilemma, Crepón et al. (2011) present a randomized analysis test that sheds more light on this phenomenon that has gained strength in developing countries with populations seeking alternatives to their economic deprivation.

The first effect found was that, for the first time, sectors of the population that had been excluded from this tool were given access to credit; another effect was that existing self-employment activities in families expanded, as shown by the increase in sales in households engaged in agricultural and livestock activities. However, they were also able to observe that due to the compensatory effects on wages due to the payment of credit, average consumption did not increase; however, there were cases of households that allocated part of their income to savings, although there were no effects on poverty reduction.

In addition, in order to access larger loans collectively, the requirements were increased since it was required to have certificates of residence and to be involved in activities other than agriculture and livestock farming. For individual loans, the eligibility criterion was based on the borrower having been carrying out the economic activity in the same physical space for at least 12 months. This seemed to coincide with the criterion of granting credit to the poor but not to the poorest, i.e., those who did not carry out economic activities of greater scope would be excluded from credit.

In this sense, the results indicate that the female participation rate was not as high as expected, nor was t h e r e a n y effect on the probability of households starting new economic activities. Similarly, the per capita consumption analyzed even two years after the start of the program did not report increases either, which reinforces the conclusion that there was no effect on poverty reduction. It seems instead that this type of financial tool allows for sustaining the economic activities of families and that the destination of the extra income, in most cases, was directed to the purchase of livestock and other savings without having a significant impact on household consumption or on the improvement of their living conditions. In terms of education, there was no significant impact on household consumption or the improvement of living conditions. The survey did find significant results that demonstrate the positive effect of the credits in this area, although it was observed that there was no increase in child labor in the households surveyed.

Finally, the heterogeneity found in the surveys showed that there was a discrepancy between households with and without self-employment activity. Households with an existing activity had an increase in their activities through growth in sales, expenses, and savings, which were associated with a reduction in consumption, mainly in social consumption. On the other hand, households with no pre-existing activity, although they increased their participation in applying for microcredits, did not have significant increases in their activities and did show an increase in consumption, mainly in food and what they call durable expenses (Crepón et al., 2011 ). In short, the richness of the study also lies in the development of a model to predict the probability of household indebtedness.

Therefore, in order to break the vicious circle of poverty, the empowerment of women is indispensable, as it can be an accelerator of economic development. Duflo's analysis shows, on the one hand, a criticism of the policy that argues that gender equality increases when poverty decreases, but this is not entirely true since actions are focused on creating conditions for economic growth but without specific strategies to improve the status of women.

On the other hand, if an environment of greater opportunities for women were to be created first, this could enhance development and thus overcome conditions of poverty. This has been emphasized in some World Bank reports, which have pointed out the need to review institutional structures to balance the gender gap and thus comply with quotas that guarantee more significant development opportunities for women. However, recommendations regarding economic growth are not enough; it is necessary to achieve equality in the political sphere and for political actions to guarantee the right to equality between men and women.

It is then a matter of seeking a balance between creating conditions of economic growth for the poorest and, at the same time, developing actions that focus on reducing the gender gap by giving more space to women. However, in the social field and within family relations, these general conceptions may not be the panacea needed for households to act in a balanced and efficient manner. It is here that Duflo's analysis acquires greater importance by emphasizing everyday situations experienced by families facing unfavorable economic conditions. By understanding how relationships between men and women develop in poor households, better public and autonomous policies can be generated to help improve the living conditions of families.

For Duflo (2011), the first way in which economic development can reduce inequality between men and women is by alleviating the constraints faced by poor households since greater economic solvency can eliminate life-and-death decisions in which women are often the most vulnerable. In extreme circumstances, differential treatment between boys and girls has been observed; for example, in the slums of New Delhi, girls are more than twice as likely to die of diarrhea if poor households are less likely to spend money on girls' health, a possible solution to this inequality could be found in public policies of free health care for the poor, which would directly benefit girls even if their parents do not change their behavior toward them.

In countries with high poverty rates, it has been shown that in times of crisis, women tend to be more vulnerable. In India, for example, the excess mortality rate of girls increases during droughts. In this scenario, although the objective is not to reduce the gender gap, increasing the economic capacity of poor households to cope with crises would substantially help women.

In addition, opening up work opportunities for women can change the family's own perception of them. If the belief that women can only dedicate themselves to domestic work and marriage is modified, the aspirations of both fathers and daughters will change, allowing girls to have greater access to education and health. To exemplify the above, we can observe the incorporation of the Indian economy into world dynamics, a phenomenon that has generated positive effects in the creation of more significant opportunities for women.

In new economic sectors such as telemarketing, new job opportunities have opened up for women who were previously excluded from the labor market, even in poor sectors. Language instruction in English for both boys and girls seems to be a trigger for equality that will allow them to insert themselves more easily into the new labor market in the future. In any case, even if policies are not designed with a gender perspective, the diversification of the economy and the increase in job opportunities that include women may cause households to transform their behavior and reduce the gaps.

In this regard, there are two central problems that must be addressed in order to stimulate structural transformations. First, the time spent on housework. Duflo emphasizes this as a severe issue in terms of gender inequality since, at all income levels, most women spend more time on housework, and this is accentuated in poor households. The fact that women are unable to develop in the labor market, allowing them to have greater independence and economic influence in the household, reduces their bargaining power within the family dynamics.

If women's time is freed up for housework, the positive effects can even be seen in improvements in coexistence and in the reduction of intra-family conflicts, as reflected in the case of poor households in Morocco which, by connecting to a drinking water network, freed up the time of the women who performed this activity and saw improvements in the reduction of stress and in the reduction of conflicts.

Secondly, fertility reduction is of vital importance in female "empowerment." As is well known, maternal mortality is a severe issue in poor countries; in turn, if women marry or become pregnant at an early age, their degree of autonomy is significantly reduced. It should be noted that in developing countries such as Mexico, family planning campaigns such as the one carried out in the 1970s, which sought to reduce the demographic boom, allowed more women to study and enter the labor market (Torres, 2000).

In addition, women's rights need to be equalized to enable their access to economic and political improvements. In some cases, it has been observed that economic growth may lead to a progression of women's rights, but this has not been sufficient to guarantee conditions of respect and equality, as can be reflected in the still low political participation of women in political positions compared to men. Although it would seem that economic development alone adjusts inequalities between men and women, this may be a hasty conclusion. The case of China, for example, which has shown significant economic growth in recent decades, exhibits a detriment in the sex ratio at birth that favors boys, and it is worrying that the phenomenon of selective abortion has spread to other countries; similarly, at the wage level, it can be seen that even in developed countries, although women have the same qualifications, they continue to earn less than men.

Duflo's (2011) analysis of women's "empowerment" is very vast and leaves many lessons on policy aspects that should be addressed, such as the very perception that families and society have about women, and that must be transformed to ensure conditions of equality between sexes (Botello and Guerrero, 2017). Increasing opportunities for women and improving their living conditions, in addition to contributing to the reduction of poverty, is an unquestionable human right, and although it seems that it will take time to close the gender gap, education and providing women with greater political and economic rights seem to be key to achieve this goal.

In this sense, public and private policies that seek to provide the poor with tools to improve their quality of life should include gender perspectives and incentives for education and health. Finally, financial education and proper family negotiation seem to be key to good decision-making within households.

5. Conclusions

Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee's experimental approach to understanding poverty, and more importantly to proposing solutions, is a hopeful proposal in the most objective sense possible. It is a new, optimistic view of economics that seeks to understand the way of life of the poor and how they cope on a day-to-day basis. When reading the social experiments and the reflections of the authors, it seems that the central question they ask themselves is: how does one survive in a state of lack? The way of answering this question is an enriching epistemological exercise by uniting several social disciplines in empirical reasoning through data, with the objective of exploring and questioning paradigms that were supposed to understand and solve the complex social phenomenon of poverty.

Indeed, a great leap is made in moving from orthodox economics to a more humanistic vision that seeks to understand and integrate the poor as subjects of the economy who, on the one hand, cause social and economic discomfort and, at the same time, suffer the effects of a marginalizing economic system that, in reality, violates fundamental human rights, such as equality among people.

In Duflo and Banerjee's work, the field study plays a primordial role, and more social variables are considered, placing people at the center of the analysis. The shift from the general to the particular as the object of research reveals a panorama that is largely forgotten by public policymakers: the context of the poor as described by the poor themselves. Under the lens of this model, different phenomena and social problems can be questioned, and more efficient alternatives can be presented.

The authors' study proposal is comprehensive and includes another series of questions on current socio-institutional issues, such as corruption, which seems to be one of the main obstacles to be overcome in order to eliminate poverty. Another virtue of the study models developed by the authors is that the method of analysis can be replicated in other latitudes; the statistical validity presented in their models allows reliable data to be obtained and, based on this reliability, better public and private policies can be generated, both in the social and family spheres. Several important conclusions can be drawn from the work of Duflo and Banerjee discussed in this paper. First, it must continue to be emphasized that the phenomenon of poverty is a global problem that needs to be addressed urgently as a matter of simple social justice. Secondly, although human development policies (support for women entrepreneurs and microcredit policies) do not totally solve the problem of poverty, they can alleviate shortages and set a course to improve the quality of life of the poor and make their choices more efficient.

On the other hand, it should not be overlooked that the prevailing economic inequality in global capitalism is a structural issue that can trap families in poverty despite autonomous attempts and policies to mitigate it. In this sense, policymakers in all nations have an ethical commitment to address the problem of inequality within countries in a sustainable manner.

Similarly, the epistemological aspect is a central aspect of the economists' proposal, as they invite public management to be a field of knowledge generation that will end up forming a set of good practices. Although the structural aspect is not the focus of attention, the contextual aspect is no less complex, given that it implies a set of dynamic factors whose intervention can provoke a diversity of processes.

In this sense, the circumstances of the context move in a temporality of short, medium, and long duration so that many of its events, situations, and conditions are not simple ephemeris of a monotonous everyday life. This is the natural territory of the human, which is not strictly homo economicus or the free rider but can always be something else. From the social emerges the multidimensional. Consequently, due to the complexity of its analysis or understanding and the epistemological and methodological issues involved, interdisciplinarity becomes the best mechanism for building some resolutions (Rao, 2008). This indicates that this goes beyond economics as a discipline; dialogue and the construction of holistic perspectives constitute a research and social management need.

text in

text in