The Inca state was the most extensive prehispanic political unit in South America, spanning from Colombia to central Chile and Argentina. Its development involved the control of various territories and ethnic groups, within a multifaceted process whose chronology and dynamics are not yet well known. For Collasuyu, the southern region of the empire, the idea of a very rapid, homogeneous, and late expansion dating back to the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui, after 1471 AD prevailed for several decades. This vision was based on a documentary analysis carried out during the mid-20th century by Rowe (1945). In recent decades, with the advancement of studies and dating techniques, archaeologists began to question this chronology (e.g., Adamska and Michczyński, 1996; Cornejo 2014; D’Altroy et al. 2007; Marsh et al. 2017; Meyers, 2016; Ogburn 2012; Raffino and Stehberg 1999; Schiacappasse 1999; Williams and D’Altroy 1998 ) and to recognize a significant variability in the strategies used to expand and consolidate the Inca territorial domain (Malpass and Alconini 2010 ). At present, there is widespread consensus on the need to reconsider the dates provided by ethnohistoric studies and to develop a chronological framework that allows a better understanding of the profound and diverse impact of Inca control in the area.

In Argentina, this interest has been accompanied by a significant increase in research focusing on the Inca domination of the region and on obtaining new radiocarbon dates. Some proposals have also been put forward regarding the time in which some territories were incorporated to the Tawantinsuyu (e.g., Marsh et al. 2017; Nielsen 1997 ), but the extent of these studies is partial. Thus, faced with the need to analyze the chronology of the Inca’s expansive - and possibly fragmentary - process in the region with a global panorama, in this paper, we look at all published 14C dates from northwest and center-west Argentina. Nevertheless, the discussion revolves around the dates corresponding to samples with detailed contextual information, which increases the possibilities of confirming that association with an event in the Inca period is correct. This, in turn, ensures the greater reliability of the chronological estimations of the development of this expansive process in each one of the areas involved.

Methodology and Samples

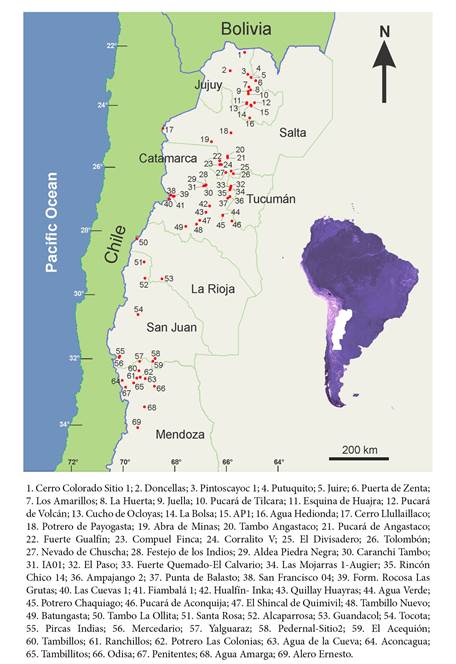

For the current study, we considered every 14C date explicitly attributed to the Inca domination that was adequately published with the corresponding laboratory code. The sample consists of 178 dates from 76 archaeological sites distributed in seven provinces in Argentina: Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan, and Mendoza (Figure 1). All of them come from archaeological contexts without materials of Spanish Colonial origin. These dates were calibrated with the Southern Hemisphere curve of the Calib7 software (Hogg et al. 2013; Stuiver and Reimer 1993 ) and, for the analysis, we considered the periods that were within two standard deviations.

Source: Alejandro García, 2020.

Figure 1 Location of the main archaeological sites mentioned in the text

The obstacles limiting the precision of radiocarbon dating corresponding to short and recent periods are widely known. Among these, we must include the error margin in dates, the diversity of analyzed materials and conditions in the processing of the samples, as well as the post-depositional alterations of contexts and/or samples (Cornejo 2014; Meyers 2016 ). Accordingly, we agree to approach this subject in terms of time periods and not of specific dates, even though we propose estimated years for the annexation of each sector of Tawantinsuyu. Given the fact that the extension of the calibrated ranges exceeds the period of analysis, and the fact that all the dates used correspond to Inca contexts that did not include Colonial elements, to interpret the data, we considered the average dates from the main distribution areas with two standard deviations (95 % probability), and only in some cases (dates from San Juan), with one standard deviation (68 % probability). Even when we acknowledge that probability distributions are not symmetrical and that the midpoints are not necessarily the dates of highest probabilities, we think that they offer fairly proximate and acceptable alternatives with which to handle the information obtained.

The quality of a 14C date depends on the degree of confidence in the archaeological context from which a sample is recovered, on the purity of the analyzed material and on the precision of the analytical method (Boaretto 2009 ). It is therefore necessary to consider whether every date linked to the problem approached here (in this case, the chronological frame of the Inca expansion) presents the same degree of confidence, since those with a high degree of uncertainty should not be considered. Do all 14C dates considered Inca dates really correspond to materials or events of that period? In order to assess the reliability of a date, several authors have proposed to rate the degree of confidence in the association between the material sample and the archaeological record or the event involved (e.g., Greco 2012; Taylor 1987; Waterbolk 1971 ). However, many articles fail to offer the information required about the contexts. So, as an alternative, this study considers three groups of dates, defined by the quantity and quality of the available contextual information for each sample and the possibility of verifying the cultural assignation proposed by each researcher.

For the dates in Group 1 (G1), detailed descriptions are provided for the location of the dated sample, the archaeological register of the dated context, its stratigraphic distribution and spatial relation with the sample. This is done so that the composition of the contexts can be reconstructed in order to verify the association with the sample and its Inca character. For dates in Group 2 (G2), the excavation, stratigraphy, and archaeological materials used are often described, but the information provided is not sufficient to adequately reconstruct the contexts and their associations with the dated samples, nor to verify their Inca character. Finally, the dates integrating Group 3 (G3) present scarce and/or imprecise information, generating important doubts about the integrity of the context, the cultural assignation, and the association with the dated sample, even in those cases where the sample was recovered in an archaeological site with Inca architecture. In this group, we included those cases in which it was not possible to verify whether the dates corresponded to an Inca occupation or not (for example, those with no association to evidence of Inca presence).

Results

After analyzing the data, 28 dates were incorporated into Group 1, most of them (19) corresponding to sites located in the province of Jujuy. Another 36 were assigned to Group 2, and the 112 remaining dates to Group 3. The greatest probability areas of the oldest dates in G1 (mostly Jujuy) essentially ranges from 1381 until 1498 cal AD. Only one date from Salta was included in G1, showing a probability area that coincides with the Inca period with an average of 1486 cal AD. The main areas of the three oldest dates from G2 range between 1390 and 1597 cal AD. The only sample from Tucumán was assigned to G3. In Catamarca, the two calibrated dates in G1 range between 1428 and 1667 cal AD, and the average for the main areas in the calibration with 1 δ is 1481 and 1502 cal AD, while the average for the case of the four oldest samples of G2 extends from 1458 until 1466 cal AD. The only group represented in La Rioja is G3. In San Juan, the main areas of the three oldest dates from G1 mainly covered the second part of 16th century, with averages ranging from 1478 to 1487 cal AD. Finally, in Mendoza, two dates in G1 obtained from the same archaeological site provided different calibrated results: 1408-1503 and 1439-1670 cal AD.

The majority of the analyses were conducted using charcoal or wood samples (n=113) that, to a greater or lesser extent, implies problems of “old wood” and delayed use of firewood (Bowman 1990 ). The presence of 20 cases with no data in terms of sample characteristics illustrates the frequent scarcity of information regarding the contexts of the dates.

Discussion

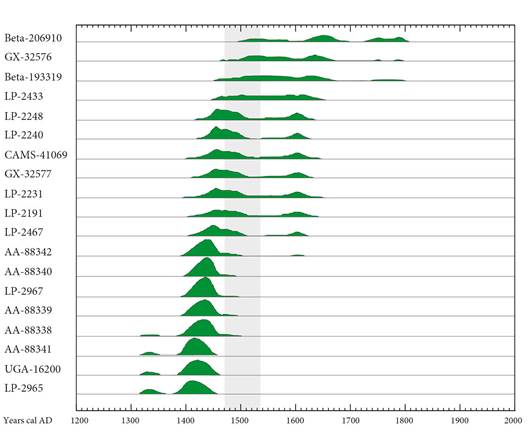

The traditional ethnohistoric proposal places the Inca entrance to northern Argentina during the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui, between 1471 and 1493 AD (Rowe 1945 ). A more recent ethnohistoric alternative proposes a slightly older entry, between 1467 and 1475 AD (Bárcena 2007). Our analyses, in concordance with previous research (D’Altroy et al. 2007; Williams 2000 ), suggest that the Inca domination of Jujuy would have started during the first half of the 15th century (G1 dates visible in Figure 2). The average date for the three oldest dates (main probability areas) is circa (ca.) 1420 cal AD, showing a certain correspondence with the earliest dates in G2 (Figure 3). These results fall within the intermediate position of 1430 and 1410 cal AD proposed by Nielsen (1996, 1997) and Palma (2000) respectively, in the first case based on the dates obtained in the archaeological site Los Amarillos (G2) and the second considering a date obtained in La Huerta de Huacalera (Raffino and Alvis 1993 ). In our case, the dates correspond to the archaeological sites Pucará de Tilcara, Esquina de Huajra, and Pintoscayoc (Cremonte et al. 2006-2007; Greco y Otero 2016; Hernández Llosas 2006; Otero 2013).

Source: Alejandro García, based on graphs obtained using the Calib 7.0.4 program, 2020.

Figure 2 Distribution areas of G1 14C calibrated dates (2σ) from Jujuy. Highlighted in grey is the traditional Inca period according to ethnohistorical sources

Source: Alejandro García, based on graphs obtained using the Calib 7.0.4 program, 2020.

Figure 3 Distribution areas of G2 14C calibrated dates (2σ) from Jujuy

The G1 date from Salta (Figure 4) falls in the second half of the 15th century, and the average of the probability area corresponding to the Inca period is 1486 cal AD. The marked difference with that of Jujuy’s dates suggests that the Capacocha of Cerro Llullaillaco was conducted a couple of decades after the Inca expansion in this sector. Capacochas were celebrated for a wide variety of reasons and not necessarily at the time of annexation of a new territory (Schroedl 2008 ). In agreement with this scenario, G2 dates show a certain delay in the annexation, considering that the earliest average is 1451 cal AD.

Source: Alejandro García, based on graphs obtained using the Calib 7.0.4 program, 2020.

Figure 4 Distribution areas of G1 (above) and G2 (below) 14C calibrated dates (2σ) from Salta

Tucumán provided only one 14C date for the period analyzed (Figure 5), whose principal area occupies the second half of 15th century (average of 1486 cal AD). Despite the fact that it corresponds to G3, it is worth noting its closeness to the oldest G1 date from the province of Catamarca (average of 1481 cal AD). The averages for the main probability areas of Catamarca’s G2 dates are only a few years older, ranging between 1458 and 1476 cal AD. Overall, these results provide evidence of the annexation of these territories during the first two or three decades of the second half of the 15th century.

Source: Alejandro García, based on graphs obtained using the Calib 7.0.4 program, 2020.

Figure 5 Distribution areas of the Tucumán (G3, above) and Catamarca’s (G1 in the center and G2 below) 14C calibrated dates (2σ)

Southwards, in La Rioja, there are no G1 dates. Most of the available analyses are from the pre-Inca village of Guandacol, in the southern extreme of the province (Bárcena 2009a; Callegari and Gonaldi 2007-2008), showing signs of architectonic modifications and later Inca occupation. Given the scarcity of contextual data, the contribution of these dates to the discussion is very limited.

In San Juan, calibration with 2σ of the G1 dates produces 95 % probability areas that are too large (Figure 6). In contrast, the 1σ calibration (68 % probability) of the three oldest dates of G1 presents "Inca" distribution areas with averages of 1478, 1487 and 1488 cal AD. These dates were obtained from Tambo de Tocota, Pedernal-Sitio 2 and Cerro Mercedario (Albero and Angiolini 1985; Berberián et al. 1981; García 2015).

Source: Alejandro García, based on graphs obtained using the Calib 7.0.4 program, 2020.

Figure 6 Distribution areas of G1 14C calibrated dates (2σ) from San Juan

These results would indicate a very late entry of the Incas to the south-central sector of San Juan, although the probability ranges of various G2 and G3 dates go back to the 14th or even the 13th century.

Finally, both G1 dates from Mendoza were obtained at the same archaeological site: Cerro Aconcagua (Figure 7). They correspond to analyses conducted on bone and hair from an individual sacrificed in a Capacocha (Bárcena 1998a; Schobinger 2001 ). The results are quite different (Table 1), as one of them points towards the mid-15th century (average 1446 cal AD for the main area), and the other shows a much wider distribution area with an average of 1554 cal AD. Beyond these differences, the problem of using these results for dating the incorporation of Mendoza to the Tawantinsuyu lies in the probable origin of the Capacocha. In fact, Cerro Aconcagua seems to have been linked mainly with the Inca occupation of the Aconcagua Valley (Central Chile) and not with that of the oriental Andean territories (Stehberg and Sotomayor 2005 ). This leads us to think that the ritual involving this human sacrifice probably originated in the current Chilean territory before the annexation of the Cuyo Valley (Mendoza). If we take the G2 dates as an alternative, the main area’s averages of the two earliest dates are 1477 and 1459 cal AD, which somewhat coincide with those obtained in San Juan. Nevertheless, the scarcity of dates does not allow us to solve the issue in this area.

Source: Alejandro García, based on graphs obtained using the Calib 7.0.4 program, 2020.

Figure 7 Distribution areas of 14C calibrated dates (above, G1; below, G2; 2σ) from Mendoza

It should be noted that Marsh et al. (2017) used Bayesian statistics to analyze the entire set of 14C and TL presumably Inca dates from Mendoza and proposed a much earlier Inca entry for this province of between ca. 1380 and 1430 cal AD. The evaluation of this interesting work requires a more extensive space than the one available here. The main problem with it is that the authors gave all the dates a high degree of confidence (including those from problematic or scarcely informed sites such as Ciénaga de Yalguaraz, Odisa, Cerro Penitentes, Tambillos, Tambillitos, and Alero Ernesto). They also failed to consider the problems with TL local dates (Bárcena 1998 a ). From our perspective, this constitutes a serious problem that undermines their conclusions.

It is also important to note that although we use the average of the main areas, the probability ranges of the dates are wider and not necessarily represented by the mid-points. The use of full probability ranges provides a more complex picture. On the one hand, in 54.5 % of the cases (n=96) it is observed that part of the probability range falls in the Colonial period. This is related to the precision of the method and calibration, since all the dates used correspond to Inca contexts that did not include Colonial elements. This makes it possible to rule out the possibility that the correct dates belong to this last period.

On the other hand, many dates have probability ranges that extend through the 13th and 14th centuries. Since the Inca state would have still been developing in the Cuzco valley during the 14th century (Bauer and Smit 2015; Covey 2003 ), previous dates should be discarded. The beginnings of the main areas of probability correspond to the end of the 14th century and first decades of the 15th: 1381 and 1382 cal AD for the oldest G1 and G2 dates from Jujuy, 1390 and 1428 cal AD for Salta (G2 and G1), 1398 (G2) and 1409 cal AD (G1) for Catamarca, 1394 cal AD (G2) for San Juan, and 1408 (G1) and 1438 cal AD (G2) for Mendoza. These dates maintain a certain progression from north to south and would indicate the possibility of expansion from Jujuy to Mendoza in less than 30 years, between 1381 and 1408 cal AD. This would represent a very rapid advance, discordant with the large quantitative and qualitative differences in the Inca archaeological records for the whole area. In addition, a beginning of the Inca expansion in Jujuy towards the end of the 14th century does not coincide with the information available for Bolivia, where this process (necessarily previous) would have begun around 1400 AD (Alconini 2016; Gyarmati and Varga 1999; Korpisaari et al. 2003; Meyers 2007, 2016; Pärssinen et al. 2003; Rivera Casanovas 2014 ).

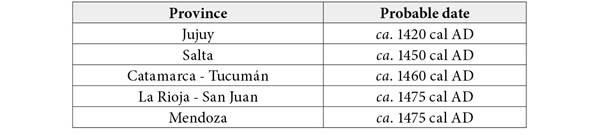

On the contrary, if we take into account the averages of the main areas of probability, the result shows a more extended progression for the beginning of the annexation process in each sector of the current Argentine territory, as suggested in Table 2.

Table 2. Approximate chronological sequence proposed for the Inca annexation of Argentine territories

Source: Alejandro García, 2020

According to this sequence, and considering the location of the analyzed archaeological sites, we can distinguish at least three stages corresponding to three sectors in the southwardly annexation process. At first, the Incas would have advanced until approximately ca. 24° S, in southern Jujuy, and followed on to the territories located in southern Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, and Catamarca up to ca. 28° S. Finally, they would have reached and incorporated those territories located until ca. 34° 30' S, in the current provinces of La Rioja, San Juan and Mendoza, a few years later. In this wide space, the chance of distinguishing at least two more advancing stages through future dates is not discarded, the latter possibly linked with the conquest of Mendoza. The ordered distribution from north to south of these sectors does not necessarily mean that this was always the course followed by the Incas. Considering the scarcity of G1 dates, especially in the southern half of the analyzed area, a larger sample is likely to provide evidence of a more complex advance, as suggested by Cornejo (2014) for the Chilean case. In fact, in San Juan there are vast territories with no evidence of Inca occupation. Nevertheless, they are located between areas effectively ruled (García 2017 a ), and it has been proposed that this space and the one corresponding to Mendoza were in fact annexed from the west (Bárcena 1992, García 2009). In sum, instead of a sequential and continuous process from north to south, the Inca expansion in Argentina probably showed interruptions and transverse movements linked to already dominated populations on the Chilean side.

This would illustrate the marked quantitative and qualitative difference in the Inca infrastructure and material culture observed between these areas of the Argentine Collasuyu. The delay in continuing the expansion southwards from Jujuy could be linked both to local resistance and to the importance assigned by the state to the domination of this area as a strategic base for future movements. Archaeological evidence of sites such as Los Amarillos and Juella (Leibowicz 2013; Nielsen 2007 ) has been interpreted as a result of abandonment related to the entrance of the Incas, and signs of destruction are evident in sites located south of Jujuy, such as Potrero de Payogasta (Salta) and Fuerte Quemado - El Calvario, in Catamarca (D’Altroy et al. 2000; Reynoso et al. 2010 ). While this, together with indications of the construction of large defensive sites (pucaras), such as Pukará Morado, Puerta de Zenta, Pucará de las Pavas, and Pucará de Aconquija (Nielsen 1996; Williams and D’Altroy 1998 ) is not undisputed evidence of resistance, it cannot be ruled out as a possible reflection of it. On the other hand, the late annexation of those territories south of ca. 30° S, bordering with the spaces occupied by hunter-gatherers, could have been linked with the low demographic density of those groups and their non-centralized political organization.

In the southern extreme, the Huarpe groups were probably not more than 30 000 individuals distributed throughout a wide space, adjacent to the south and east with non-sedentary populations (Comechingones, Pampas and Puelches). It is true that Inca domination was very strong in Central Chile, where local populations would also have followed a village settlement pattern. However, for the previous 1500 years, both sides of the Andes show remarkable differences of cultural development within the same socio-political organization class (i.e., tribal), which are reflected both in the characteristics and visibility of the archaeological records (Falabella et al. 2016; García 2017 b ). Thus, dozens of habitation sites and cemeteries have been studied on the Chilean side, while in the Huarpe area, despite the intense work conducted during recent decades, remains of just one village and one cemetery have been found in San Juan (Cerro Calvario; Gambier 2000 ) and in northwest Mendoza (Rusconi 1962 ), respectively. The uneven degree of elaboration of some handicraft goods (mainly pottery) is another element that reflects the differences in the complexity between the eastern and western village organizations, undoubtedly related to significantly disparate levels in terms of demography and population concentration. Therefore, the presence of multiple groups of low demographic density and the absence of centralized authorities in San Juan and Mendoza could have constituted an obstacle for the advance of the Inca domain, in the same way as it did later for the Spaniards (García 2004). Hence, it is not surprising that the Incas prioritized the control of central Chile, and that the Cuyo territory was annexed decades later, based on consolidated power on the Chilean side. Besides, the advance through this area could have also been related to the interests of Chilean Diaguitas, the principal allied in this part of the Collasuyu.

In turn, this panorama suggests a marked variability in the development of the successive borders resulting from the advance towards the south. The configuration of the boundaries must have depended on a series of factors (Williams and D´Altroy 1998 ), such as the degree of local resistance, the importance of local resources, the demographic and organizational characteristics of each population, and the mode of control over each region (direct, indirect, or delegated, sensuLima Tórrez 2005 ). The presence of state fortifications in the tropical flanks of northwest Argentina could respond to the need to defend against possible attacks by eastern groups, such as the Guarani (Raffino and Stehberg 1999 ). In the south of Catamarca, on the other hand, the absence of fortresses would indicate a more stable and controlled situation, probably related to the lower demographic density, and economic, and sociopolitical level of the native groups in the area.

Another important aspect to highlight is the scarce quantity of dates corresponding to G1 (n=28), representing only a 15.7 % of the assemblage. If we exclude the dates obtained from the archaeological sites of Esquina de Huajra and Pucará de Tilcara (n=18), the percentage diminishes to 5.6 %, which corresponds to only 8 of the 74 remaining sites. In contrast, most of the dates (n=114) correspond to G3 (64 %), and many of them are simply referenced as “Inca” for their likely spatial association with sites, architecture or objects of Inca provenance, without any contextual information of the sample guaranteeing such assertion. The need to improve the transmission of the information of the dated samples and their cultural contexts is evident; the confidence inspired by this data should rest on the detailed and precise presentation of dated materials and associated elements, rather than on the authority of the researchers. In this sense, it is worth noting the scarce reference to post-depositional alteration studies in articles referring to Inca dates. Many dates were obtained in residential sites, and are very likely to have been altered because of the great possibility that they may have been modified, given their normal use and posterior formation process. Thus, these aspects must be approached as accurately as possible, in order to increase the level of confidence in our chronological dates.

Finally, the chronological differences of our results with the traditional historical view are evident, but also with those archaeological approaches that trace the inclusion of some of these territories back to the 14th century (Marsh et al. 2017; Schiappacasse 1999 ).

Conclusions

Although obtaining an exact chronology for the Inca expansion is not possible, conducting an analysis providing an approximate chronological frame for this process is feasible. The earliest ages of the main probability areas of the best-informed 14C dates suggest that the Incas were able to incorporate Jujuy ca. 1381 cal AD, and reach Mendoza ca. 1408 cal AD. Nevertheless, this chronology would not be coherent with that of the beginning of the Inca expansion out of Cuzco and with the archaeological records for Collasuyu. It also seems not to adjust to the time required to successfully annex such a vast territory.

Alternatively, the mid-points of those ranges indicate that the Inca annexation of the western Argentine territories would have initiated in ca. 22° S towards 1420 cal AD and would have reached ca. 29°-33° S in the second half of the 15th century, perhaps ca. 1475 cal AD.

These dates are far from those traditionally proposed in ethnohistorical research. Indeed, the latter should be abandoned as a general chronological framework to understand the Inca expansion to the south, as has been repeatedly pointed out by various archaeologists in recent decades.

The rhythm of advance towards the south would have been articulated with the political and economic situation in the rest of the Empire, but organizational structures of local populations and available local resources could have played an important role as well. In this sense, the chronology obtained reflects a notable state interest in securing dominion primarily over the densely populated territories in the Quebrada de Humahuaca and surrounding areas before continuing the advance southwards, as well as a late interest in villages with low demographic density located beyond ca. 31° S.

Finally, it is important to highlight the scarcity of precise context data from the dated samples, which constitutes a difficult problem to solve that considered into account in future fieldwork and articles concerning the topic.