Introduction

Brazil occupies an extensive territory of 8.5 million km2 where just over 203 million inhabitants currently live. Like many Latin American neighbors, it is a country marked by extreme regional, urban, social, and political inequalities that affect the collective life of most of its population, especially its socioeconomic status located in the lower positions of the social hierarchies. Among the most serious social problems it is inevitable to recognize the growth of crime and interpersonal, collective and, more recently, political violence. Between 2011 and 2021, almost 616,095 homicides were recorded (IPEA-FBSP, 2023). A substantial part of these deaths results from disputes in the domain of organized crime, especially around illegal drug trafficking, whose daily presence in the neighborhoods that make up the so-called peripheries poses challenges to the democratic control of public order and the state monopoly of violence.

The growth of urban violence coincides with the final years of the civil-military dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1988). With the transition to the democratic regime, it was expected that institutional violence and political repression, practiced by the authoritarian regime against political dissent, would be eradicated. It was believed that the restoration of the rule of law would lead Brazilian society towards internal pacification. That's not what happened. Since the beginning of the 1980s, citizens from different social classes began to express concerns about the daily recurrence of violent crimes and attacks against people and property. As crime rates have increased demands for more law and order intensified. The public authorities' response came immediately, in the form of repression and the use of abusive use of coercive force, after all, there was no rupture in the violent institutional practices of the police throughout the transition period and even the consolidation of the democratic regime.

The contradictions soon became evident. How can we contain crimes and violence without resorting to the repressive practices of the recent past? Unlike a large majority of citizens who supported heavy-handed policies, part of the citizens supported both policies to protect the human rights of anyone, regardless of differences in class and power, and policies to modernize agencies that make up the criminal justice system in Brazil, especially civil and military police, judicial agencies, and prisons. The context is accompanied by the emergence of human rights defense movements that will oppose public security policies implemented by state governments. Its initial strategies consisted mainly of reporting cases of serious human rights violations and exerting pressure on public authorities to investigate and punish those responsible.

At the same time, in the academic world, groups of researchers recognized that there was no tradition of scientific studies in Brazil, especially in the field of humanities and social sciences, that could respond to the main public concerns as well as provide support for the formulation and implementation of policies of security and justice appropriate to the democratic society that is being consolidated in Brazil. It was necessary to understand, through socio-anthropological investigations, what challenges the persistence of violence and crime, as well as traditional security policies, represent for the future of democratic order in contemporary Brazilian society. The emergence over more than three decades of research centers that contributed to qualifying the public debate and forwarding government proposals was fundamental. This essay focuses precisely on this last aspect. It seeks to highlight the main characteristics of this social process as well as its main actors, their strategies and lines of social action, the resources they used and, to a certain extent, some of the disputes in which they were involved.

Our starting point is the hypothesis, according to which the participation of actors in the scientific field was fundamental as it produced changes in collective mentalities and influenced public opinion makers. With the results of their studies and research, they contributed to the reconstruction of official crime statistics, to modernizing policing guidelines, to monitoring serious human rights violations, to disseminating updated information on the use of new technologies in public security and to the general criticism of the negative effects produced by traditional law and order policies. The importance of these actors can also be assessed by criteria such as: frequency of participation in public debates, especially those broadcasted by the printed and electronic media as well as by social networks, in courses to disseminate knowledge to broad audiences, in partnerships with governmental and nongovernmental organizations to develop intervention programs in critical situations. In fact, these actors have also contributed to strengthening the lexicon of concepts and the repertoire of arguments used by human rights defense movements. This results in a unique association between knowledge and practices; between knowledge and the power to transform social scenarios.

Theoretical framework and methodological approach

To explore this hypothesis, the theoretical axis lies in the conceptual framework offered by the theory of collective action. This theory and its variants are based on the concept of social action as formulated by Max Weber (1974). However, when we talk about collective action we are referring not just to individual actors, but collective actors. It is primarily about understanding how different collective actors influence each other, pursuing common or divergent objectives, instrumental or evaluative, employing material or symbolic resources or means and aiming at decision making. Pursuing a flow of collective actions that converge to transform social scenarios requires considering: (a) the relative autonomy of actors in their choices and social interactions; (b) its capacity for creation, invention and originality (agency) despite external pressures exerted by normative sanctions and social regulations (social structure); (c) the prior stock of knowledge that presupposes skills, abilities, moral commitments, behavior patterns, interaction rituals; (d) the relationship networks in which the different actors are linked; (e) the actors' reflexivity based on three constitutive elements: interactional, projective and practical-evaluative, which involves taking into account the actors' dispositions for judgment, including evaluative judgment. (Dawe, 1978; Emirbayer and Mishe, 1998).

Based on this theoretical and conceptual approach, this article seeks to analyze collective actions triggered by determined actors-social scientists- in their aim to build specialized knowledge about the dynamics of crime and violence in Brazilian society since the democratic transition. To this end, it empirically seeks to understand how research centers were constituted, based on what intellectual and political motivations, as well as what means and material resources they used, how they organized their research agendas, what institutional exchanges they established among themselves, and what means they used to disseminate their research findings beyond the traditional instruments of academic communication, such as publications and participation in specialized forums. Finally, what original responses were proposed to the emerging problems with the growth of violence and crimes, aiming to pressure governments to make decisions capable of guaranteeing law and order in the context of protecting and promoting a culture of human rights.

This article is part of a broader research project that investigates the new meanings of violence in contemporary Brazilian society supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). From a methodological point of view, it is documentary research. In the documentary collection, we sought to focus on collective actors moving according to determined rational objectives, within social and institutional networks. Given the nature of the investigation, it was necessary, prior to the analysis, to criticize the documentary sources, as none of them are neutral. Although it is not possible to achieve the "true document", separating the facts from their representations, including ideological ones, the investigation used techniques capable of explaining the social bases underlying different reports. These techniques consisted of compiling different documents on the same facts, evaluating the scope of statistics, identifying the corporate origins of individual actors, placing the statements in time and in the corresponding spaces.

The research that guides this article has as its empirical universe of investigation the creation of a line of research - sociology of violence - and its development over the last four decades (1980-2020). Sociology of violence is understood here as a broader line, not restricted to this scientific disciplinary field. It also includes studies in the fields of anthropology, political science, history, human geography, and even public health. It is based on data extracted from documentary sources, such as research reports, NGO reports, official documents, press reports, statistical data. At the same time, it draws on the author's experience as one of the founders and researchers of the Center for the Study of Violence, based at the University of São Paulo (NEV-USP), one of the reference centers in this field.

The following text is divided into three parts. Initially, a contextualization of the growth of crime and violence since the democratic transition until today. Next, the exhibition focuses on the academic field and the production of knowledge. The conclusion seeks to return to the central hypothesis previously announced considering the theoretical and methodological approach adopted.

Democratic transition, growth of violence, public unrest

Following trends towards political polarization in Latin America since the 1970s, military forces associated with the economic and political elite carried out a coup d'état in Brazil in March 1964, under the argument of containing the advance of communism in this society. The established political regime not only suppressed fundamental rights and fiercely persecuted political dissent but forced many political activists into hiding and exile. To achieve its anti-revolutionary purposes, it re-equipped the instruments and equipment of political repression. Consequently, it encouraged a social environment of fear, insecurity, and distrust among civilians, which did not exclude the practice of informing on the involvement of neighbors, acquaintances and co-workers with movements or opinions challenging the authoritarian regime. Thus, it stimulated the division of Brazilian society into opposite poles, further aggravating the social inequalities inherited from Portuguese colonial domination and the existence of three centuries of slavery.

It was from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s that the steps towards a return to the rule of law became more evident. Gradually, perceptions spread, notably through the alternative press and debates in public forums, that Brazilian society was immersed in an acute institutional crisis, associated with the so-called new social movements (Cardoso, 2011), these feelings rekindled the political will to return to a democratic normality. This desire immediately demanded the interruption of the cycle of institutional violence sustained by the authoritarian government. This context ended up encouraging the emergence and multiplication of human rights defense movements throughout the country that demanded direct elections for the presidency of the republic, the end of the civil-military dictatorship and the restitution of civil and political rights to the Brazilian people.

However, this same social and political situation watched uneasily, at the end of the 1970s and throughout the 1990s, the rise of violent crime, initially in the metropolitan regions of Rio de Janeiro and S. Paulo. Police and judicial forces, deeply conservative, committed to the authoritarian past, continued to enjoy a privileged position within the State apparatus. They were not completely demobilized or displaced from their posts even after redemocratization. Under this condition they managed to weaken fundamental arguments of thought and movements in defense of human rights, such as the universality of application of these rights, including for those suspected of being responsible for the occurrence of crimes.

To better understand this social and political context that stimulated reactions from civil society through human rights defense movements, some data make it possible to better illustrate these trends and social processes that are inherent to it.

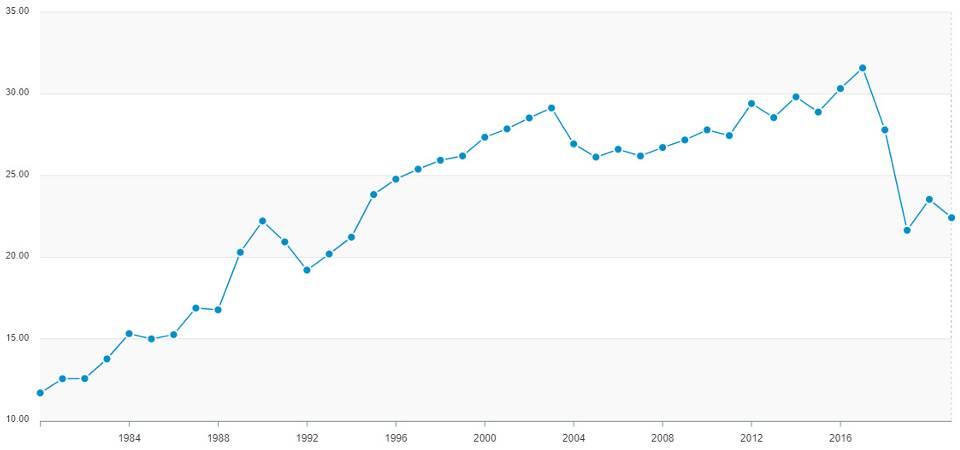

The following data illustrate the evolution of homicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants, in Brazil, between 1980 and 2022.

Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics -IBGE1 - https://www.ipea.gov.br/atlasviolencia/dados-series/20

Figure 1. Homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants. Brazil, 1980-2021

In 1980, the rate was 11.69 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. They evolved to 22.42 homicides in 2021. In the historical series, the first wave of growth occurred between 1984 and 1990, in which there was a rate of 22.22 homicides. In several capitals of the country, the absolute numbers reveal a concentration of intentional deaths in just two capitals: Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Brazil registered 32,015 homicides, Rio de Janeiro 2,912 homicides and São Paulo, the largest and richest capital in the country, 6,105 homicides in 1990. In the same year the two capitals accounted for 9,017 homicides, that is, they concentrated 28.17% of all these occurrences (Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada - Ipea, 2023). In the city of São Paulo, the rate per 100,000 inhabitants was 35.2, therefore 1/3 higher than the national rate (SEADE, 1981-95; Caldeira, 2000 and Nery, 2016). It was a period also characterized by the recurrence of cases of murders of children and adolescents throughout the country (Movimento Nacional de Meninos e Meninas de Rúa, 1991 and Castro, 1993), in addition to lynchings (Martins, 2015), summary executions carried out by death squads (Justiça Global, 2008), deaths carried out by police officers (Pinheiro, 1997).

After two years of decline (1991 -92), a new growing wave of intentional deaths covers the period from 1993 to 2004, when the rate reaches 29.14 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants (Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada - Ipea, 2023). Therefore, a growth of around 250% in 10 years. It is worth highlighting that, during the 1990s, cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro continued to present rates per 100,000 inhabitants well above the national averages, as did other Brazilian capitals in the Northeast of the country, one of the regions with the highest concentration of indicators of social inequalities. However, starting in 2000, homicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants began to decline in the State of São Paulo and in the capital city. After reaching a peak of 52.4 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 1999, it reached 39.9 homicides in 2004, still very high. In 2013, the rate reached 10.3 homicides (Seade - Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados, 2022), remaining on this downward trend until recently.

In subsequent years, between 2005 and 2021, the evolution of homicides in the country fluctuated from falling to increasing. Between 2005 and 2011, there was a downward trend, then a growth with high rates between 2016 and 2017. Afterwards, there was a downward trend again. Considering the period from 2011 to 2021, the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants fell by 18.3%.2 During the period, 616,095 intentional deaths were recorded. The overall rate was 22.4 deaths, which means that the country returned to the 1990 level (Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada - Ipea, 2023). However, this trend does not reflect regional and local realities.

Since its beginning, the period has been characterized by deaths in interpersonal conflicts, comprising fatal outcomes in relationships between known people, such as family members, friends, co-workers, and people who frequent bars and places of popular leisure. They result from disagreements in domestic and close relationships, in affective and loving relationships, or tensions in the world of work and employment (for example, between employers and employees and between colleagues in the same occupational sector). These conflicts also involve disputes over opinions on matters regarding diverse situations (such as football, religion, politics, gender) and by momentary disagreements in the streets, such as vehicle traffic conflicts, cross-eyed glances from one to the other, or motivated by disagreements in the sharing of stolen goods. At first glance, the nature of these conflicts, predominantly reaching spheres of personal and intersubjective existence, suggests the recurrence of scenarios and social environments of low tolerance, extreme irritability, as well as a weak willingness to accept norms, to share collective efforts, to exercise solidarity with the suffering of others and to exercise each one's part in social discipline.

Simultaneously with the growth in homicides, the prison population is growing as well, a result of government policies to combat crime and delinquency. In 1969, the beginning of the historical series, there were 28,538 prisoners in Brazil; it jumped to 211,953 in 2000. In 2006, there were 401,236 prisoners; in 2012, 548,003; in 2018, 744,216; and, in 2022, 832,295 prisoners. Initially, the rate per 100,000 inhabitants was 30 prisoners: at the end of the period, 409.8, a growth of around 1.266% in 53 years. Therefore, in the context of public security, the situation was not peaceful either.3 According to analyzes (Adorno and Salla, 2014) it was the policy of massive incarceration, under precarious conditions of existence in penitentiary establishments, that was responsible for the formation of factions and their strengthening, for the local increase in deaths both inside and outside prisons and due to the expansion of organized crime notably around illegal drug trafficking.

At the same time the beginning of this period is characterized by the arrival of organized crime, around illegal drug trafficking intensifying and aggravating the disputes between criminals for control of territories and between them and the police, already embryonic for at least two previous decades, and which gained a lot of visibility in Rio de Janeiro at that time. Comando Vermelho (CV), Terceiro Comando Puro (TCP) and Amigos dos Amigos have established solid connections between favela neighborhoods and prisons over the last 4 decades. The arrival of organized crime in the neighborhoods that make up the urban periphery of the metropolis ended up transforming the illegal sale of drugs into big business attracting young people to carry out various tasks such as taking drugs to buyers, monitoring the point of sale, and anticipating the announcement of police presence in drug trade areas. Anthropologist Alba Zaluar (2004) was a pioneer in drawing attention to the impact that these fatal conflicts associated with organized crime had on the evolution of homicide rates (Zaluar and Barcellos, 2014). In São Paulo, the progressive trend towards a drop in homicides was contemporaneous with the strengthening of the presence of the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) both in State prisons and in neighborhoods where low-income workers are concentrated. It was a progressive strengthening achieved in disputes between this organization and other factions, which resulted in the hegemony of the PCC inside prisons and its leadership in organizing rebellions such those occurred in 2001, 2006 and 2012. (Dias, 2013; Adorno and Dias, 2016).

Based on the above, a first conclusion stands out: a mix of governmental inertia with the internal contradictions of organized civil society created powerful obstacles preventing collective actions towards the modernization of the field of public security in the context of the culture of protection and promotion of human rights. At least four scenarios illustrate the persistence of conservative public security policies unable to face the new emerging crime economy with the spread of illegal activities in the country on a globalized scale.

Firstly, the alternation in power of progressive and conservative governments has not altered the authoritarian legacies rooted in the field of public security, despite the institutional changes that have been introduced both in criminal legislation and in the design of law and order enforcement institutions. In the period from 1994 to 2022, eight National Public Security Plans were created. The center-left governments (Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula da Silva) started by diagnosing the main problems that affected the efficient functioning of legal control of crimes and violence. The diagnoses highlighted problems related to the lack of coordination between federal and state bodies, the lack of specialized material and human resources, the lack of professional training of police officers, the persistence of traditional policies that were unable to respond to the problems posed by the emergence of the new economy of organized crime and its consequent social rooting, the failure to confront institutional violence, especially deaths committed by police officers and mistreatment including torture in prisons. In addition, the low rates of criminal inquiries responsible for high rates of impunity fueled collective feelings of fear and insecurity and even popular support for heavy-handed policies.

In particular, the center-left governments Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1994-2002) and Lula da Silva (2003-2010) revealed great protagonism in the area with the introduction of institutional innovations, including the creation of a National Public Security System (SUSP), the Law of Combating Organized Crime (Law 9034/1995), the creation of the National Public Security Secretariat (2004), and the establishment of three National Human Rights Program (PNDH). Above all, we sought to articulate the purpose of guaranteeing law and order in the context of promoting human rights, incorporating social actions in the field of public security. These initiatives required intense participation from civil society through human rights defense movements and the participation of universities and research centers in the development of projects and action plans. Civil representations took place in the councils responsible for formulating and implementing regulations, intervention projects and institutional reform of police and judicial agencies, as well as crime reduction plans, especially homicides.

Despite the government's intentions to modernize this area of public management, the National Plans failed. Its reasons are multiple and even complex. The young Brazilian democracy had not yet accumulated government experience in terms of successfully managing conflicting interests involving civil and military bureaucracies, popular participation, and the dynamics specific to the political establishment in the parliamentary sphere. Some parties opposing the governments expressed clear commitments to proposals that sought to limit the autonomy of agents and their agencies in carrying out their constitutional tasks of law and order. Furthermore, demands from organized civil society encompassed diverse focuses such as combating racism, gender violence, mistreatment of children and the elderly, along with crimes related to everyday delinquency. As a result, different defense movements of civil rights often tended to contradict each other, weakening actions capable of ensuring common understandings regarding the application of laws. Added to this scenario the fragility of some government plans that seemed to lack focus, objectivity and were lost in general principles.

A second aspect was the expansion, throughout the national territory, of criminal factions previously confined to the Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo axis, dominated by Comando Vermelho and the PCC. As of the 2010s, local factions were formed in the North and Northeast regions of the country. According to a survey carried out by the Special Election Yearbook (2018-2022) (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública - FBSP, 2022), 53 factions were identified, operating throughout the national territory. The São Paulo and Rio factions had presences in all states of the federation. The PCC is only not present in two states: Mato Grosso and Rio de Janeiro. (Muniz and Dias, 2022; Manso and Dias, 2018; Vasconcelos and Silva, 2023; Siqueira and Raiva, 2019). Furthermore, the emergence of militias4, especially in Rio de Janeiro, further aggravated this scenario (Manso, 2020; Couto and Beato Filho, 2019).

Little has been done by the public authorities to contain this expansion, mainly its connections with other criminal groups in Latin America. In the same sense, civil society has sought to monitor events, such as prison riots, prison escapes, and executions by death squads. To this end, local observatories were created with the purpose of storing information and thereby strengthening public debates. However, its effects on public security policies aimed at containing this expansion were limited.

A third aspect is the persistence of police violence resulting in deaths of civilians. Since the end of the authoritarian regime, civil society has organized itself to denounce these cases of violence and to propose institutional solutions. Nevertheless, the results have been frustrating. Between 2014 and 2022, the trend was towards an increase in cases both in terms of absolute numbers and in percentage. This trend worsened as the federal government administration transitioned from a progressive center-left government (Dilma Rouseff), more favorable to controlling police actions in the fight against crime, to conservative and far-right governments (Temer and Bolsonaro), more complicit in institutional violence.

It is not surprising that almost 30% of these death cases are concentrated in Rio de Janeiro, where police interventions in areas with a large concentration of residents in favelas and precarious housing are common. Recurring in the national and international media, such cases have mobilized public opinion through civil society actions, also promoting the creation of observatories to monitor police operations in these areas, which result in a high number of victims. Examples can be found in the websites Rede de Observatórios da see gurança (https://observatorioseguranca.com.br/) and in the non-governmental organization Fogo Cruzado (https://fogocruzado.org.br/).

Table 1 below illustrates this trend towards persistence and growth in the number of cases:

Table 1. Deaths resulting from police intervention. Brazil, 2014-2022

| Year | Administration | Numbers | %* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | progressive | 3.146 | 5,26 |

| 2015 | progressive | 3330 | 5,69 |

| 2016 | progressive | 4240 | 6,88 |

| 2017 | conservative | 5179 | 8,08 |

| 2018 | conservative | 6220 | 10,84 |

| 2019 | conservative | 6351 | 13,3 |

| 2020 | conservative | 6413 | 12,81 |

| 2021 | conservative | 6493 | 13,43 |

| 2022 | conservative | 6429 | 13,56 |

Source: Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, vários anos *Percentage of all the other intentional deaths

Finally, a fourth aspect concerns the setback in public disarmament policy. Since the issue of crime and violence became a public issue in post-dictatorship Brazilian society, currents of opinion began to question the civilian population's access to firearms and to suspect that the growth of crimes was related to the spread of these means of physical coercion. Even though the firearms market was almost restricted to professionals in the areas of public security, criminal justice, the army, and other armed forces, many of them circulated without strict legal controls and police supervision, encouraging the development of a clandestine and illegal market. Aware of this possible association between firearms and the increase in homicides, researchers and non-governmental organizations began to question the public authorities held responsible for the fragility of legal controls and the lack of statistical data to monitor the evolution of possession and carrying of these weapons. At the same time, they were encouraged to develop studies, based on rigorous methodology, to assess the extent to which permissive legislation in connection with the absence of institutional controls had an impact on the increase in crimes involving intentional deaths (Peres, 2004; Cerqueira and Mello, 2012).

Stimulated by the results of these studies, the debate intensified, not without conflicts and serious opposition, including from social groups with political representation supported by national firearms manufacturers. It resulted in the publication of the Statute of Disarmament (Law N° 10,826/03. December, 2003). The legal act created the National Arms System (Sistema Nacional de Armas - SINARM), as well as establishing the requirement for the registration of firearms, requirements for acquisition, prohibition of possession except in cases permitted by law, employment in private security companies, the competence of the bodies regulators such as the Federal Police. It also established sanctions in case of non-compliance with the rules and established a list of prohibitions regarding the possession and carrying of firearms.

Still strong political opposition to the Statute has remained over the years expressed by parliamentarians identified with conservative sectors and the extreme right as well as by sectors of civil society notably defenders of harsher punishment. During the Bolsonaro government (2019-2022), as part of his campaign promises, the former president suspended, through decrees and regulations, controls on the possession of firearms, providing broad access. To have an idea of what these measures meant, during the four years of the Bolsonaro government, 1.3 million new firearms were registered in circulation (Brasil de fato, 2023).

Given this scenario, public security policies tended to become more repressive and violent. Police and institutional violence became recurrent on the streets, in public housing and inside prisons. At the same time, opinion polls showed that citizens were increasingly worried about future scenarios. On the one hand they were concerned about the increase in crimes. In their demonstrations, there were also frequent perceptions that crimes were not being punished in proportion to their growth and worsening. Criminal impunity seemed to be the rule. On the other hand, these same citizens did not see short-term solutions that were not based on repression, harsher sentences, and mass incarceration. We were thus faced with a paradoxical scenario that required further steps. It required overcoming conflicts between right and left, between order and human rights, between applying the law according to constitutional precepts and the use of unlimited force to contain crime and violence at any cost even if this meant restricting rights. In this context the potential victims of institutional violence have remained the same for more than four decades: black, poor, peripheral, that is, residents of large urban agglomerations with a concentration of low-income workers, especially those linked to the informal market. What to do then?

From facts to academic knowledge

Therefore, in the first three decades of the democratic transition (1970-2000), conflicts and contradictions between authoritarian legacies became more evident. Struggles for the return to the rule of law and legal control of crimes and violence intensified. The situation was accompanied by collective feelings of fear and insecurity. Popular demands for harsher measures concerning law enforcement, including calls for the indiscriminate use of coercive force under the responsibility of the police were becoming intense. There were no reasonable understandings between these groups - politicians, government officials, executives of the civil bureaucracy, agents of the institutions responsible for law and order, professionals of the armed forces and the police - and the groups involved in the defense of human rights.

As public debates emerged, especially stimulated by the national and regional press and electronic media, the problems arising from the growth of crimes and different types of violence began to interest social scientists. On the one hand the media images conveyed through mass communication allowed us to glimpse scenarios of citizens, often identified as belonging to the professionalized urban middle classes, cornered by threats against their physical integrity and personal honor as well as personal property. On the other hand, these images seemed to reveal scenarios of neighborhoods with a large concentration of residents belonging to the lower strata of socioeconomic hierarchies, made up mostly of low-income workers from different sectors of the industrial economy, commerce, and services as if to suggest associations between poverty, crime, and violence. For social scientists, it was inevitable to recognize that the most vulnerable victims preferentially comprised residents of large popular housing of those conglomerates. Although these segments were often blamed for the growth of urban violence, it was within their ranks that intentional or unintentional deaths caused by interpersonal conflicts, gangs fights or violent police action, were concentrated.

Slowly intellectualized segments of Brazilian society were consolidating the understanding according to which the persistence of violence and the greater vulnerability of these poor citizens, unprotected by the laws, compromised the consolidation of democracy in Brazil. And, certainly, one of the reasons that worsened this scenario was the way in which the public authorities, through their agencies legally controlled public order. The forces of law and order faced crime as if it were a war between good men and criminals. In turn, criminals appeared represented among groups of young, poor, black people, residents of urban outskirts seen as potential criminals.

Initially the arrival of violence and crime as an object of knowledge of social sciences in the Brazilian academic world was timid. Crime and violence occupied a marginal position in the major debates regarding economic development, government policies and the future of democracy. These were topics that were not very prestigious among academic peers. Many of them considered violence and crime as a kind of pathological consequences of the way capitalism had expanded in this society, worsening social inequalities, and polarizing the interests of groups and social classes. Four decades (1980-2020) passed for the field of sociology of violence to gain relevance, legitimacy, and scientific and political density. It is not the purpose of this article to describe or analyze the details of this building process of scientific field within sociology and social sciences in general. In any case, to understand the line of argument that has been adopted it is necessary to at least outline the lines of action that resulted in the consolidation of a field of investigation and specialized knowledge with national and international recognition.

When the first concerns about the growth of crimes and violence came to the public arena at the end of the 70s, still during the civil-military dictatorship, some prestigious intellectuals, social scientists, and historians began to be questioned in public debates about the explanatory causes of this. It is never too much to remember the eagerness with which journalists and opinion makers wanted ready answers with indications of reasonable and practical solutions. However, at that time, there was no accumulated knowledge in this field in the Brazilian academic world, as there had been for more than a century in countries such as the United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy.5To answer the public unrests, some of those intellectuals sought inspiration in some familiar readings, especially those who had done their postgraduate studies at American and English universities. Others were inspired by well-known theses of social thought identified with Marxist and socialist traditions that associated crime with poverty. Of course, the explanations soon revealed themselves to be unsatisfactory and lacking empirical support.

This panorama of scarcity regarding specialized knowledge in the country began to be faced in the next generation of researchers. Lima and Ration (2011) coordinated a project that sought to identify and explore the relationships between social sciences and the pioneers of studies on crime, violence, and human rights in Brazil. The project resulted in a collection bringing together interviews with 16 researchers from different teaching and research institutions who contributed to guide themes and questions, carrying out research projects, teaching courses, training new researchers, publishing results of their research and participating in academic forums. A reading of this collection highlights at least two aspects: firstly, except for two among the group of researchers interviewed, most of the pioneers did not begin their academic careers choosing crime and violence as their field of study. Secondly, the vast majority started working with other researchers, including assistants such as undergraduate and graduate students. In a subsequent moment, collective scientific work gave rise to the creation of regional research centers that, a little later, will converge towards the creation of national networks with international connections.

Some examples can be mentioned. The anthropologist Alba Zaluar, who played a prominent role in the violence field studies and in public debates, began her career by conducting studies on popular religiosity and popular organizations in favelas in Rio de Janeiro, which led to her famous PhD in social anthropology at the University of São Paulo in 1984 (Zaluar, 1985). One of the chapters of this reference book dealt with coexistence in the same social space between workers and criminals, which sparked intense academic and public debate. This was her entry into the field of anthropology and sociology of violence. César Barreira, from the University of Ceará had also written a PhD in sociology at USP, whose object was the relations between power structures and social movements in the wilderness at the northeast of the country. It was this study that led him to the themes and issues pertinent to political and social violence. Raulo Sérgio Pinheiro who introduced human rights into university's research program, completed his doctoral thesis at Science Politique in Paris on the Brazilian working class during the first Republic (1888-1930). The author of this article is also listed among the 16 pioneers.

Therefore, for most of these intellectuals and researchers, their arrival in the field of study was lateral and even accidental. Certainly, the social pressures of the situation, the incentives provided by preliminary studies carried out as well as the challenge of offering consistent responses to legitimate concerns related to the legal control of public order influenced personal decision-making in terms of the future of the academic career. The challenge involved establishing connections between studies on crime, violence, security and justice policies, and human rights with academic debates on the transition and consolidation of democracy in contemporary Brazilian society.

Most of these pioneers belonged to public or private universities or maintained links with research centers in the areas of humanities and social sciences, where they developed research projects. At the beginning, investigation activities encountered numerous obstacles. There was no collection of reliable statistical data or historical series that would allow analyzing the evolution of crimes, trends in violence, processes of criminalization of behavior, operations of law and order agencies such as police stations and prisons, as well as related topics. There were also no documentary databases or files whose sources were accessible and whose consultation made it possible to extract data capable of supporting the answers to the main questions formulated in the projects. Furthermore, essential sources, such as police inquiries, were practically inaccessible due to the enormous distrust of those responsible for the archives regarding the interests of researchers. These public authorities considered the presence of external observers inappropriate because they believed that those ones could, enjoying a privileged position, denounce institutional abuses or serious human rights violations committed by institutional agents. In prisons, the situation of difficulties was not different. Ultimately the distrust was reciprocal and did not facilitate the creation of an environment conducive to original investigations based on fieldwork.

Other difficulties revolved around researchers' lack of familiarity with research traditions in the area. The international reference literature was still little known (Cardia and Adorno, 2002). Academic works that were the original foundations of this scientific field slowly entered socio-anthropological courses and investigations. The most penetrating works and authors were limited to the universe of symbolic interactionism, such as Goffman (1961) and Becker (1963). Classic references such as studies by Cohen (1955), Sykes (1958), Matza (1964), or Cicourel (1968) were not even translated to Portuguese language. More recently, the exceptional book by Whyte ([1943] 2005) and the classic Rusch and Kirchheimer ([1939] 1999) were translated. This last one is quoted by Michel Foucault whose work Discipline and Punish (1979) fueled increasing interest greater not only for the study of prisons and punitive power.

Step by step, this bibliography, as well as other references, were incorporated into undergraduate and graduate courses, in the social sciences and humanities. They were also discussed in seminars that brought together professors and researchers at different stages of training, from scientific initiation to post-doctorate. The socialization of knowledge contributed to the definition of lines of research - for example, epidemiology of violence; institutional violence; social control, criminal justice; serious human rights violations; violence and citizen security; criminal justice system organizations; beliefs, values and representations about crime, violence, criminals, and criminality; the city and organized forms of violence; public and private security, among others. At the same time methodological programs and strategies were developed by training researchers in qualitative fieldwork techniques, quantitative data processing and statistical model building, as well as critical analysis of data and information sources.

The socialization of knowledge was possible due to a characteristic of the organization of scientific work that was established from the beginning of the process: the building of research groups that were created and institutionalized in universities and research centers, initially in some states of the federation, and today present in almost everyone. A survey carried out in the Directory of Research Groups of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq (https://dgp.cnpq.br/dgp/faces/consulta/consulta_parametrizada.jsf ) identified, according to the last census (2016), 1009 records of a line of research on violence in general and 838 groups that have this keyword as their institutional identification as well as their line of research. Among these countless research groups, the table below identifies those that began at least 10 years ago and that enjoy academic recognition and frequent presence in the public debate.

ISER was created in 1970, in the city of Campinas and transferred to Rio de Janeiro in 1979. Although it does not focus exclusively on the themes of violence and human rights since its creation it has developed studies along these lines. NECVU-UFRJ has to its credit varied research projects, mainly emphasized on copious studies on police inquiries, on public security at national borders, on management of police expert reports, and on the police records in cases of alleged resistance to authority. CLAVIS' contribution was to highlight the importance of the epidemiological perspective in the study of violence. It also drew attention to the study of police work conditions, focusing on situations of risk and emotional and mental stress that characterize the work of security professionals especially those who monitor the streets and face crime and its threats on a daily surveillance. In turn, adopting a predominantly ethnographic approach and exploring a diversity of research themes, INCT-InEAC (UFF-RJ) has contributed to highlighting the singularities of the violence world focusing the security and criminal justice system in Brazil. One of its main objective is to dispel myths regarding forms of legal and social control in this society. CeSEC has had an outstanding importance in this panorama. In addition to monitoring police violence against favela residents in Rio de Janeiro as well as reference studies on racism in police actions, it has been promoting campaigns aimed at changing drug policy.

Table 2. Research Center. Violence, Crime, Public Security, Human Rights, Citizenship, Democracy

| Identification | acronym | university | year | site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instituto de Estudos da Religião | ISER | 1970 | https://iser.org.br/ | |

| Núcleo de Estudos de Cidadania, Conflitos e Urbana | NECVU | UFRJ | 1999 | http://necvu.com.br/ |

| Centro de Estudos de Segurança e Cidadania | CESeC | UCM | 2000 | https://cesecseguranca.com.br/ |

| Centro Latino-Americano de Estudos de Violência Saúde Jorge Careli | CLAVES | FIOCRUZ | 1988 | https://www.ensD.fiocruz.br/portalensp/departamento/claves |

| Instituto de Estudos Comparados em Administração de Conflitos | INCT- InEAC | UFF | 2009 | https://www.ineac.uff.br/ |

| Núcleo de Estudos da Violência | NEV- CEPID | USP | 1987 | https://nev.prp.usp.br/ |

| Fundação Joio Pinheiro | FJP | 1987 | https://fjp.mg.gov.br/produtos/ | |

| Centro de Estudos de Criminalidade e Segurança Pública | CRISP | UFMG | 1996 | Centro%20de%20Estudos%20de9620Cnrrinat>dade%20e%20S«Eoran%C3%A7a%20P%C39èBAbt.ca&taEstfUE |

| Grupo de Pesquisa Violência e Cidadania | GPVC | UFRGS | 1995 | https://www.ufrgs.br/gpvc/ |

| Núcleo de Pesquisa sobre Violência e Segurança | NEVIS | UnB | 2006 | https://www.pucrs.br/direito/pesquisa/observatorio-em-seguranca- |

| Laboratório de Estudos da Violência | LEV | UFC | 1994 | https://lev.ufc.br/ https://linktr.ee/levufc |

Source: Brazilian national Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq_ Directory of research Group, https://lattes.cnpq.br/web/dgp

Although the João Pinheiro Foundation (Minas Gerais) deals with other lines of research and government plans, it was one of the pioneers in promoting this area of knowledge by hosting, at the end of the 1980s, a seminar that brought together some of the pioneers previously mentioned. Likewise, it stands out for having hosted the first comparative research on the profile of the prison population of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro (1984). The final report of the research, coordinated by Antonio Luiz Paixão (MG) and Edmundo Campos Coelho (RJ), gave rise to two publications, which are still references in prison studies today (Paixão, 1987; Coelho, 2005). The CRISP-UFMG has sought to respond to problems related to the evolution of crimes, police performance, domestic violence, and prison policy. It was one of the pioneering centers in the use of methodologies for urban crime mapping.

The GPVC-UFRGS brought together researchers who sought to address a diverse range of problems related to violence and public security in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Among its productions, national and international comparative studies on police organizations and professionalization are relevant. It is also worth mentioning the publication of a series of prominent books on violence in this state of the federation. The theme and institutional problems of police organizations, civil and military, also attracted the attention of NEVIS- UnB researchers. In addition to the singularities of the presence of these forces in the capital of the Brazilian Republic, studies did not stop at analyzing facts and structures. They also directed their attention to the perspective of social representations, that is, to the way in which public security professionals understand, justify, and symbolize the world of crime and its figurations, as well as police operations and professional performance. The LEV-UFC dedicated its efforts to describing and understanding local realities, exploring the connections between violence, crime, and power structures, both in the countryside and in cities, with a focus on the formation of gangs and organized crime.

NEV-USP, one of the oldest, was created with the aim of explaining the persistence of serious human rights violations despite the return of Brazilian society to the democratic regime and the Rule of Law. It played an innovative role both in guiding research themes and questions, and in its methodological approaches. Its pioneering spirit is revealed in the scope of objects to which its researchers dedicated themselves: the use of lethal force by the police; the contacts of urban populations with the world of crime and violence; social attitudes and values regarding justice and security policies; the daily attacks committed against vulnerable groups to the protection of their rights, such as women, children, the elderly, black people and indigenous people notably against their right to life; living conditions in prisons; the city and violence; the challenges of organized crime to the preservation of the democratic order.

The NEV also innovated in the creation of databases extracted from different sources (official crime data, data from the national press), and in the monitoring of serious human rights violations through the periodic publication of yearbooks. Likewise, it innovated concerning the articulation between research and teaching for academic audiences in undergraduate and graduate courses and for non-academic audiences. It was the headquarters of the National Institute of Science and Technology - INCT-CNPq Violence, Citizenship and Citizen Security and, since 2002, it has been the headquarters of the Research, Innovation and Dissemination Center (RIDC), funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (https://cepid.fapesp.br/en), whose institutional model foresees a kind of communication chain between the production and dissemination of knowledge, education, technological innovation and dissemination of knowledge to inform public policies. Since its creation, NEV has established as an institutional axis the connections between research, intervention in governance problems and transformation of mentalities, aiming to guarantee the legitimacy of the democratic society.

It is not strange that during 40 years countless reviews of national specialized literature have been produced (Adorno, 1993; Lima, Kant and Miranda, 2000; Zaluar, 2004; Salla, 2006; Adorno and Barreira, 2010; Santos and Barreira, 2016; Campos and Alvarez, 2017; Costa and Lima, 2018; Muniz, Caruso and Freitas, 2018; Ratton, 2018; Ribeiro and Teixeira, 2018; Fachinetto et al., 2020). It is also worth noting that this vast bibliographical production has been receiving public funding since its early years from the main funding agencies such as the already mentioned FAPESP, along with other state foundations as well as the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq, the Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education - CAPES, and the Brazilian Innovation Agency - FINER International agencies such as the FORD Foundation, the European Community, the MacArthur Foundation, Open Society, the World Bank, the Konrad Adenauer Foundation among others contributed as well. In addition, the international exchange programs provided by several countries, especially the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Portugal, Spain, France, Germany, and more recently Asian countries such as Japan and China.

Funding has covered different types of support, such as institutional operations, lines of research, scholarships for different stages of training, institutional exchange, and participation in scientific events. All these combined actions and initiatives contributed to increasing the proportion of masters and doctors in this area of knowledge, the bibliographic production published by means of qualified journalsin Brazil and abroad, the participation of Brazilian researchers in the main scientific forums, such as the periodic meetings of the National Association of Postgraduate Studies and Research in Social Sciences - ANPOCS, Brazilian Anthropology Association- ABA, Brazilian Political Science Association - ABCP, Brazilian Sociological Society - SBS, Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science - SBPC, American Anthropological Association - AAA, International Political Science Association - IPSA, International Sociological Association - ISA, Latin American Studies Association - LASA.

This institutional and scientific dynamic ultimately expanded the presence of scientific research on crime, violence, public security, human rights, and criminal justice in the increasingly globalized academic world. It also contributed to refining the mechanisms and methodologies of communication, both scientific and aimed at broad and even specialized audiences such as educators, opinion makers, parliamentary advisors and of course citizens connected with the main challenges of the present time.

If, on the one hand, the incorporation of the sociology of violence as a scientific discipline with academic status was becoming an undeniable reality, on the other hand, this raised classic questions about what this same discipline had to offer as a solution to the social area problems. In other words, how to translate this scientific knowledge into a sociology of the social problems of violence to identify ways of overcoming them. It is therefore about associating knowledge and power (Foucault, 1979). Social scientists faced then some imperatives: to participate more actively in the formulation and implementation of public security and justice policies; to occupy executive positions at different levels of the state bureaucracy aiming to directly influence the implementation of institutional guidelines; to write regularly for qualified public opinion dissemination bodies; to propose innovative action plans, such as programs to reduce homicides or provide shelter for children, adolescents and young adults in situations of social vulnerability; and to participate in the organized civil society organizations focused on the production and management of data on crimes, violence, justice and public security. There were still other urgent tasks: To formulate a specific language that would make it possible to translate the results of sociological research to be understood by ordinary citizens unfamiliar with the common scientific language of academic studies. It was necessary to learn how to speak to non-academic audiences without trivializing scientific knowledge. Training was also required for the construction and management of databases, for the access to electronic sources of information and specially for social communication through broad and concentrated use of the social networks that were being created. Therefore, these social scientists learned to make use of various digital media, such as websites, podcasts, video production, WhatsApp, platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter with the purpose of achieving greater efficiency in social communication. This strategy aimed and still aims to influence collective mentalities by adapting them to the values of democratic political culture and respect for human rights.

Conclusion: From academia to civil society

This academic dynamic led to consequences among which at least two stand out: the achievement of scientific legitimacy in the field of sociology of violence and the constitution of movements and networks in civil society to denounce serious violations of human rights and to present proposals for forwarding problems in public security and justice. Gradually social scientists are being recognized as spokespeople for what science has to say about the world of crime and violence. They become public intellectuals. They are called to participate in different public debates, influence public security and justice policies, combat prejudices and mistaken political proposals, advise governmental and non- governmental organizations. Some are recognized as "experts", a designation that deserves to be better qualified.

If the incorporation of the sociology of violence as a scientific discipline with academic status was becoming a tangible reality, at the same time classic questions arose regarding what this same discipline had to offer as practical solutions. In other words, how to translate this scientific knowledge into a sociology of the social problems of violence and what ways to overcome them. Social scientists faced some imperatives: to participate more actively in the formulation and implementation of public security and justice policies; to occupy executive positions at different levels of the state bureaucracy; to write regularly for qualified public opinion organizations; to propose innovative action plans such as programs to reduce homicides or provide shelter for children, adolescents and young adults in situations of social vulnerability; and to participate in the creation of organized civil society organizations focused on the production and management of data on crimes, violence, justice and public security.

Numerous non-governmental organizations have been created in the last four decades to monitor serious human rights violations and propose action plans to reduce crimes and violence, most of them associated with groups of researchers and research centers with national and international recognition. Along with those created in the democratic transition, such as the Teotônio Vilela Commission, the Justice and Peace Commission and Global Justice, new agencies emerged such as Fogo Cruzado and the Network of Security Observatories, already mentioned, as well as Instituto Sou da Raz and Instituto Igarapé, each of them acting in specific areas such as weapons, police violence, violence against women, children and adolescents, and institutional racism.

In this scenario, Brazilian Forum on Public Safety - FBSP (https://forumseguranca.org.br/ ) undoubtedly stands out. Founded with the purpose of creating favorable conditions to stimulate technical cooperation in the field of public security, it brings together researchers, social scientists, public managers, federal, civil, and military police officers, justice operators and civil society professionals, i.e. the criminal justice system operators. The FBSP is responsible for numerous projects, including the Public Security Yearbook, the Atlas of Violence in partnership with the Institute for Applied Economic Research - IPEA, Cartographies of Violence in the Amazon, Structural Racism in Public Security, Violence against Girls, and Women. FBSP is responsible for editing the Brazilian Public Security Magazine and the Fonte Segura Bulletin. It has been considered a qualified spokesperson for print and electronic media, researchers, and government officials, having collaborated in numerous public security policies formulation and implementation initiatives. (Vasconcelos, 2022).

Finally, as we tried to suggest, the failure of public security policies in contemporary Brazilian society is not due to a lack of research, information, proposals, and initiatives from organized civil society that has fulfilled its civic missions by combining scientific knowledge, more specifically sociological, with the possibilities and alternatives for transforming the current situation of violence and crime in the country. Contrary to what Foucault thought, knowledge is not always power. The problem is not a lack of knowledge. The problem is not the translation of research findings into governmental action plans and programs nor the communication of these results to the inclusive society and opinion makers. The problem is deeply political. It deals with the power relations between the different actors operating in the field of public security, in a scenario of disputes involving actors positioned in a polarized way.