Introduction

The origin or evolution of any security institution creates power conflicts inside governments worldwide. Security organizations have strategic goals that produce interagency conflicts such as the achievement of political (access to strategic decision-making) or economic (the budget of security agencies that in the case of Mexico is about 10 billion USD) power. Other factors include the number of members of an institution and the struggle for technology, armament and equipment (Rodriguez and Le Clercq, 2019). Nevertheless, the most important power, that which legitimizes, gives responsibility and as such, provides political, economic and budget foundations, is the legal power.

Without a law or constitutional rule, security institutions are in a legal interregnum to demand for new resources to operate. Thus, former National Defense Secretary Salvador Cienfuegos (2012-2018), unsuccessfully promoted an Internal Security Act to consolidate the power of the Armed Forces in the security strategy. However, the current political and resource war that law enforcement agencies are experiencing is due to the creation of the National Guard.

Mexico's political opposition (pan, PRI, PRD and mc) demonstrated political will to block constitutional changes that required more votes than those obtained by the coalition supporting the president. Creating an intermediary military-oriented security body by a Constitutional reform was a hazardous political bet for the Mexican government. In legal and operational terms, it was far easier to increase the force of the Federal Police (pf, by its Spanish acronym) from the National Gendarmerie with the support of the Armed Forces. Nevertheless, Lopez Obrador was backed by the opposition in reforming the constitution and, thus created the National Guard. The government is now allocating the Army and Navy budget to train and recruit new members for the National Guard. According to Security Secretary Alfonso Durazo, the ideal force of this new institution should be around 100 and 150 thousand officers.

Lopez Obrador's administration made a cost-benefit analysis in order to make this decision. This implied that the fastest, most efficient and least expensive route to create the National Guard was to entrust this responsibility to the Armed Forces. The Mexican Armed Forces (Army and Navy) is an institution that, per se, has five clear advantages to achieve this goal: a) discipline and military doctrine; b) military facilities across the country to train and host this new intermediary institution; c) mobility for deployment at a national level; d) officers and commanders to lead the strategic zones; and e) a combined force of about 45,000 military police and navy officers.

Mexican Armed Forces more frequently get involved in activities that are within the jurisdiction of civilian authorities. There is a responsibility to create a national police service with a true state of force that allows quasi ever-present territorial deployment. In this sense, the Armed Forces and civilian institutions have to understand that the military-civil post-revolutionary pact (Serrano, 1995) should be re-addressed in the framework of a new country, taking into account the complexity of the public agenda and politicization (i.e., the increase of political actors with multiple stakes). On the other hand, from the governmental-civilian and social points of view, there is a movement that opposes the structural participation of the Armed Forces in the civilian arena. This reflects the growing disapproval of the Armed Forces in the public opinion and the continual criticism of this reality by national and international media.

Therefore, this paper seeks to answer the following questions: Which are the institutional reasons and policies behind these changes in the Mexican Army? Are there institutional incentives in the Mexican Armed Forces that promote these changes? Is there a regional agenda, supported by the United States, to promote these changes? Which are the medium -and long-term- challenges of these changes in the Mexican Army?

In order to answer them, this paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the framework that explains the evolution of military institutions in the security area as a path dependence phenomenon (Mahoney, 2001 & Pierson, 2000, 2004) that is not exempt from the power-seeking fight within the country (Rodríguez, 2017) and which responds to the theory of evolution of security institutions (Zegart, 1999).

Discussion

I. Institutional incentives, struggle for power and evolution of security institutions in Mexico

The Mexican Armed Forces' participation in internal security activities is not new; nonetheless, they have been continuously used in public security matters since the administration of former President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012). The deployment pattern of the Army and Navy in these activities continued and deepened during Enrique Peña Nieto's administration (2012-2018) with the approval of the Internal Security Act, which finalized with a greater constitutional reform in the early days of the administration of current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018-).

This is a reminder that once a country has begun an institutional path, reverse-related costs are high. As Margaret Levi (1997) argued, there might be other choosing points, but the arrangements of certain institutional accords might obstruct an easy change of the initial choice (as cited in Pierson, 2000, p. 28)1.

Source: Aguilar Romero (2019).

Figure 1 Path dependence on the Armed Forces used for public security issues.

In this sense, path dependence processes can operate to institutionalize political arrangements that turn out to be particularly vulnerable to any event or process that comes in a later stage of the political development (Pierson, 2004). This translates in how path dependence works to shield decisions and arrangements, even when there are governmental changes or potential future political party transitions that are usual in the Mexican political scene.

This is especially important within the Mexican national context taking into consideration that changes of government affect previously established objectives, the design and implementation of policies, as well as the continuity of formulations and decisions. In this sense, it is essential to identify the main objective of each administration to point out motives for decisions and vulnerabilities throughout the period studied. Thus, political change or stability must be considered as an important factor to shield the research of these types of narratives, losing the institutional approach.

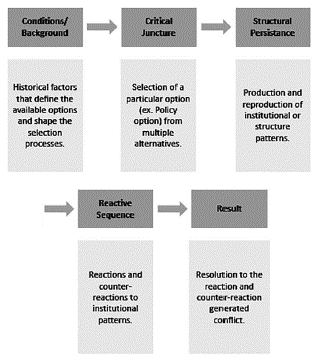

Figure 2 shows the analytical structure of an argument with a path dependence approach extrapolated to the political arena in order to understand the institutional results but, most importantly, how processes are implemented. According to Pierson (2004), there are four interconnected political issues, meaning that each one of these characteristics make political and institutional inertias prevail.

Source: Mahoney (2001).

Figure 2 Analytical structure of an explanation from a path dependence approach.

Firstly, the main role of collective action is established. In politics, the consequences of the actions of an actor highly depend on other people's actions. An important factor is the absence of a linear relation between effort and effect. In those circumstances in which making a decision would generate high costs, actors must constantly adjust their behavior to the potential actions of other actors. If there is a decision to create a new political party, join a coalition or provide resources to a stakeholder, it will depend on the probability that other actors make the same decision (Pierson, 2004).

The second characteristic refers to the high density of institutions. Institutions and policies to invest in specialization deepen relations with other actors, whereas developing particular social and political identities motivate both individuals and organizations. This causes greater attraction towards current institutional accords with regard to other hypothetic alternatives.

Actually, in institutionally dense environments, the main actions set the individual behavior towards difficult reverse paths (social actors make decisions and commitments based on current institutions and policies). Given this, there are two possible sources of path dependence in politics: power dynamics and social understanding patterns (Pierson, 2004).

The third characteristic is set in terms of power as the possibility of using political authority to enhance power asymmetries. Actors can use such authority to change the rules of the game -through institutions and different policies- in order to strengthen their power. This not only produces a change of rules on their favor but also increases their own capacities to act politically and, at the same time, decreases their rival's capacities. These changes also result in adaptations that reinforce these tendencies towards uncertain, poorly engaged or vulnerable actors joining the winners or leaving the losers -change of party or interests in their parliamentary group- (Pierson, 2004).

Accordingly, Pierson concludes that minor events that happen at the right moment can have greater and ever-lasting consequences, but the timing of these events is crucial because early events in a sequence are more important than the subsequent ones. In fact, an event that occurs 'too late' might not have effects, even when it shows that it might have had big consequences if the timing had been different. Finally, the key point within path dependence is inertia, because once the process is established, positive feedback -meaning measures or policies at different levels driven towards the same objective- moves towards the same equilibrium and probably this is going to be change-averse to subsequent events.

Pattern dependence on the Armed Forces for public security operations

Mexico's military body has been directed (from its origins) towards the confrontation of internal threats and problems. Combined with the decomposition of public security and justice bodies, this has generated an expansion of the Armed Forces, which has noticeably increased since the 2000's (Moloeznik, 2008). Nevertheless, civilian authorities' low development levels and lack of capacity depends greatly on the preferential support of military authorities.

In addition, the paradigm that favors the continuity of the Armed Forces is the one generated between national security, within their jurisdiction, and public security, within the civilian authority, particularly considering that inter-governmental strategies at different levels of government have been a failure as they ignore structural variables. The complexity of national security agencies which deal with a lack of compatibility facing the public security agencies stands out as the main issue. There are other situations such as budget allocated, social and economic perspective of each type of agency (Rodríguez, 2017).

The Armed Forces are designed and appointed to safeguard national security, that is, against scenarios in which "any of the main elements of the state such as the incumbent government, institutions, population, as well as national sovereignty and territorial integrity" are threatened (Rodríguez, 2017, p. 19). However, military corporations are progressively involved in activities pertaining to civilian authorities. This is presented in the first attributions changes, meaning that they have changed from the defense of sovereignty and national defense to tasks such as:

destruction of drug growing areas, public safety actions, cleaning and reconstructing areas affected by natural disasters, reforestation in certain regions, reducing illiteracy, battling guerillas, direct fight against organized crime, reconstructing police institutions at federal, state and municipal levels, disaster zone protection, human remains recovery missions, safeguarding strategic facilities, security during electoral periods, public health crusades and attention to pandemics, among other problems (Rodríguez, 2017, p. 134).

Power maximization conflict

The conflict between organizations to achieve the maximization of power can be explained by greater political attention from the president in order to promote personal and institutional agendas, and the presence of a struggle to reach bigger budgets in order to have more institutional capabilities, therefore causing conflicts for legal power (Rodríguez, 2017).

One of the best examples of a power maximization conflict can be seen in a diplomatic cable from the United States Embassy in Mexico (2010) that points out how "Mexican security institutions often are seen as a sum-zero competition in which the success of an agency is seen as the failure of another; the information is carefully kept and the joint operations are almost unknown".

High-level political attention (political capital). Clearly, the conflict to get the attention of the president or political leader damages the intergovernmental coordination of cabinets. The secretary that best fulfills the president's instructions has a better chance to convey his necessities in order to accomplish their missions. This can be seen reflected in the allocation of higher economic resources when compared with other security institutions.

Fighting for budget (economic power). "Budget allocation" was identified as one of the main causes of structural conflict between national security organizations that has a direct effect on their coordination. The fight for budget cannot be left out of the political conflict between SEDEÑA and CNS in 2013 and 2014 over the affiliation of the Gendarmerie to any of these institutions. Capacity-building, even if it is just for some two thousand new officers of the federal civilian or military law enforcement agencies, requires a significant amount of extraordinary public financing, doctrine instruction and operational training of new cadres. Additional funding resources in any institution help to legally finance technical and administrative areas, as well as to build or remodel facilities. The mandate to equip new members creates new opportunity areas for financing other institutional capacities that can be shared with the rest of the organization or assigned internally, for example, when there are armament and equipment industries.

Theory of the origin and evolution of national security agencies

The theory of the origin and evolution of national security agencies as proposed by Zegart (1999, p. 336) is highly useful to understand power dynamics among the actors involved, such as the government, congress, political parties and other social actors. Zegart points out that the Executive prevails in decision-making regarding institutional changes over the rest of the actors that want to participate in the construction and evolution of a country's national security agencies. Zegart's propositions that explain the original process of construction and evolution of national security agencies are the following:

Proposition 1: The executive branch drives the creation of national security agencies. Congress plays, at best, only a secondary role.

Proposition 2: In national security affairs, existing bureaucratic actors have much to gain or lose with the creation of a new agency and will ight to preserve their own institutional interests.

Proposition 3: The evolution of national security agencies, like their creation, is driven by forces within the executive branch -by the president, by the agency itself, and by its supporters and opponents in other bureaucratic offices.

Proposition 4: National security agencies develop with sporadic, largely ineffectual oversight by the Congress. Members have neither the incentives nor the capabilities to keep constant watch over agency activities.

ii. Background of the use of the Armed Forces in public security matters

Participation of the Armed Forces in public security has been intricately linked to different strategies against drug trafficking. This phenomenon is relevant for two reasons, irst, because it has been the factor that has determined the different national or public security strategies, and second, because the fight against drug trafficking should not be a matter of national security but public safety. According to Rosas, Dammert, Magaloni, Ungar, and Secretaría de Seguridad Pública (2012), a partial preventive model, the right intelligence system and a justice system could face this threat directly and robustly. The previous analysis is essential to this research because it allows to identify the initial moments and the strengthening of the convergence between military and civilian institutions.

Therefore, it is necessary to start with the moment in which the Armed Forces began to fight drug trafficking. The Mexican Army has participated in anti-drug missions since 1938, when former President Lázaro Cárdenas attempted to put narcotics production under State control. Nonetheless, Luis Astorga mentions that it officially began in 1947 with the "participation of the Armed Forces in the fight against drugs and the creation of the Security Federal Direction (DFS, by its Spanish acronym) with personnel enrolled in the Army" and the support of units such as the 10th Infantry Battalion or the 18th Cavalry and aircraft Regiment to locate plantations (as cited in García Luna, 2018, p. 25). After this, in 1948, the 'Great campaign' began, which entailed the manual destruction of illicit crops (García Luna, 2018).

The 'Canador Plan' started in 1996, which stands out because it was the first massive deployment of military troops for the task of eliminating plantations, with approximately 1,500 to 3,000 officers. In 1970, the Army and Air Force implemented strategies with the inhabitants of mountain areas to persuade them of dropping poppy and marihuana growing and harvesting, in addition to urging them to identify or break up drug trafficking organizations (Mendoza, 2016). When president Luis Echeverría took office, anti-narcotics police groups were created with the objective of stopping the market that would potentially surpass governmental control (Toro, M. in Aguayo, S. in Mendoza, 2016).

Further on, the Condor Operation was implemented in 1977 and focused on drawing the attention to the 'Golden Triangle,' comprising Sinaloa, Chihuahua and Durango, especially the mountain area. Nevertheless, according to the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) report, the mission had difficulties such as land access, aerial support, limited intelligence and communications capabilities.

In this sense, it was specified that the missions also sought to eliminate plantations, control of illegal trails and shutting down illegal laboratories (as cited in Mendoza, 2016).

In 1986, during Miguel de la Madrid's presidential term, the special forces unit was created in the Army, called the Special Forces Aeromobile Group (GAFE, by its Spanish acronym). The next year, the Mars Assignment Force began, which was the Condor Operation renamed (García Luna, 2018). That same year, the Armed Forces were integrated to the brand-new National Civil Protection System -created in response to the earthquakes occurred in September 19th, 1985, to face potential emergencies and natural disasters-, a situation that has allowed for projecting a positive and reliable image to society (Moloeznik, 2008).

In this context, drug trafficking was typified as a national security threat in 1970; nonetheless, it was not until 1987 when Mexican president Miguel de la Madrid declared drug trafficking as a national security problem, and its control as a state matter (Mendoza, 2016). This statement is a critical situation, considering that both drug trafficking and organized crime permeated -and it has remained so to this date- security institutions at all levels. In practice, these phenomena are related to public security, which eases the convergence of attributions both for the military and for police corporations. As Barrón (2004) expounds, the nature of drug trafficking poses the convergence of situations such as sovereignty, national security and corruption, but mainly, the subordination of the Armed Forces to civilian authorities, which leads to turn its organizations into hybrid police/military institutions.

In the 1990s the creation of the Control and Detection System through Mexican radars for detecting aircrafts that smuggled drugs into the country took place. In this period, there were several updates to the basic structure of the Navy, such as the release of their internal regulation in which drug-trafficking fight was the most important responsibility. Furthermore, one of the highest national violence levels was reported, especially towards the end of Carlos Salinas de Gortari's presidential term (Escalante, 2009).

In this period, there was another critical juncture of the Armed Forces. The process of enlargement of their attributions continued because of the resolution of the Supreme Court (SCJN, by its Spanish acronym) that established that the three forces could "participate in civilian actions in favor of public security aiding civilian authorities" (as cited in Moloeznik, 2008). In other words, it is not limited exclusively to drug-trafficking fight, but recognizes the support to the population in disasters or weather contingencies -(the DN-III-E plan and the SM-AM-90 plan)-, reforestation and re-vitalization of ecosystems, and even vaccination tasks and cholera prevention within the Solidarity Program framework (Juárez, 2016).

On the other hand, Armed Forces were deployed with the emergence of the National Liberation Zapatist Army (EZLN, by its Spanish acronym). According to the official version, this meant the retreat of the armed body to the jungle, enclosing and containing the threat, under the argument of the constitutional attribution that established as a "requirement of the government, to keep and safeguard the country's internal and public peace" (Salinas as cited in Juárez, 2016, p. 233).

Ernesto Zedillo's presidential term was characterized by important events. First, the amendment to Article 21 of the Mexican Constitution on December 31st, 1995, stands out. This meant the first reference to the concept of public security in a document with federal jurisdiction in the following paragraphs:

...Public security is a task entrusted to the Federation, the Federal District, states and municipalities, in the respective competences established in the Constitution. The actions of the police will be ruled by the principles of legality, efficiency, professionalism and integrity.

The Federation, Federal District, states and municipalities will be coordinated in the terms pointed out in the law to establish a national public security system. (as cited in Regino, 2007)

However, this adaptation did not translate into a better development of the concept and much less into its recognition as a fundamental right for Mexican citizens. In consequence, the General Act that established the coordination bases of the National Public Security System was passed in 1995. This new law stated a new approach to public security, maintaining the joint responsibility of the Federation, Federal District, States and Municipalities for public security. Thus, the attribution is of a state nature and it focuses on the prevention, prosecution of offences and crimes, imposition of administrative sanctions, reintegration of criminals and minor perpetrators, and all those that "contribute to achieving higher goals and safeguarding people's integrity and rights, as well as preserving liberties, order and public peace" (Ulloa, 2000).

Establishing and setting the concept of public security became more complex when this was identified in the projection of the sectoral program, announcing elements that usually favor its own militarization. In 1995, as part of his first government report, the President announced the initiative of the Federal Organized Crime Act. When announcing their arguments, president Ernesto Zedillo stated that drug trafficking was the biggest threat to national security and revealed an increase in crime rates of organized groups which jeopardize, as a whole, the coexistence, values and traditions of the Mexican people.

In spite of the aforementioned analysis, in 1999 the Senate approved an initiative to create a Preventive Federal Police (PFP, by its Spanish acronym), comprising 4,800 officers, whose objective was to organize and watch over the operation of the pf. By the time, Ernesto Zedillo's speech had evolved into one that recognized the necessity of putting law enforcement first because "public security and justice represent a main duty of the state" (as cited in Juárez, 2016, p. 239) and that all previously strategies implemented had failed, concluding with the statement that all measures would be taken to avoid further failure. It is important to mention that this new institution also proposed the grouping of all the federal corporations, something that did not happened (Regino, 2007).

The transition to democracy in 2000 represented a breaking point in the civil-military relation, because so far in history, both Mexico and military institutions had matured in a political scenario dominated by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI, by its Spanish acronym). As Moloeznik (2008) establishes, "a party other than PRI taking office, after the victory of Vicente Fox, brought out the institutionalism of the Mexican Armed Forces. Political alternation surpassed the litmus test." For the first time, the Executive and as such, the commander-in-chief, represented a new vision that sought out immediate legitimacy from military corporations on a national level.

In his inaugural address, Vicente Fox recognized a strong linkage between military institutions and public security when he mentioned that:

their loyalty to the Republic [of the Armed Forces], their strict compliance with their constitutional duties, their exemplary role in the drug-trafficking fight and civil protection and respect to the political processes of the country have become a key guarantee of democracy (Fox, 2000).

Moreover, he stated that a "new political future, after 71 years" was coming, and recognized the existence of "inertias and atavisms." This speech allowed him to position a state reform through which he sought to demolish insecurity and topple impunity (Fox, 2000). As such, in security matters there were important modifications as well as the creation of new bodies.

In 2001, the Public Security Secretariat (SSP, by its Spanish acronym) was created alongside the reform of the Attorney General's Office (PGR, by its Spanish acronym), both proposals previously made by his predecessor Ernesto Zedillo. The SSP, with its new legal framework, had the main objective of fighting organized crime through the coordination and unification of state and municipal governmental efforts. Nonetheless, when combating organized crime, the work of four institutions, the SSP, the PGR, the Navy and National Defense Secretaries (Juárez, 2016), was clearly recognized.

From that point on, SEDENA established that "the main objective of Mexican militaries is to combat drug-trafficking and public insecurity," (as cited in Moloeznik, 2008, p. 161). With the previous information, it is easy to identify that this statement depended strongly on the Supreme Court ruling of 1996 about the power of the Armed Forces to participate in civilian activities in favor of public security.

That year, the Federal Investigation Agency (AFI, by its Spanish acronym) was created as the operational arm within the administrative structure of the PGR. Nonetheless, it points out that it was enriched with former militaries and that the personnel received training in a semi-militarized environment (PGR, 2012). During 2002, the then National Defense Secretary, General Gerardo Clemente Ricardo Vega García, recognized that "the Army, in its behavior and actions, is indisputably subject by law to civilian authority" (Vega-García, 2003). This represented an imminent declaration of loyalty towards President Fox.

In this way, history confirms the construction of path dependence of the Mexican Armed Forces in public security matters. The central events that preceded the declaration of war on drugs by Felipe Calderón are: the declaration that classified the drug-trafficking fight as a national security matter; the resolution of the SCJN that authorized the Armed Forces to participate in public security issues to support civilian authorities; and the creation of the PFP with 4,800 military members.

Felipe Calderón: War on drugs

Genaro García Luna (2018), Public Security Secretary during the administration of Felipe Calderón, stated that in the last 40 years there was structural and investment abandonment of police institutions at the municipal and state levels in Mexico.

Therefore, corruption took place when using the economic resources that originated from crime activities carried out by the police itself -such as bribery and handouts- to finance operational costs that were not satisfied. García Luna (2018) explains that in this scenario, he put forward the proposal of using military personnel. After this decision, the strategy was to block the institutional development of police officers, but also wearing the Armed Forces down in its new activities as a supporter of the civilian authority. This represents the construction and first step towards path dependence, making it a critical juncture.

In the 2007-2012 National Development Plan (PND, by its Spanish acronym) there were two central points for our analysis: organized crime and law enforcement institutions. About organized crime, it was recognized that these groups represented a strong threat to national security and the resources derived from illicit activities facilitate the conditions to overcome the capacities of police bodies in charge of fighting and prevention of organized crime. So, the necessity of collaboration with the Armed Forces is reaffirmed (Gobierno Federal, 2008).

Due to state weakness, one of the objectives, specifically number 8, was to regain the State strength and security in social coexistence through the direct and successful confrontation of drug-trafficking and other expressions of organized crime. This was composed of four strategies; nonetheless, only the first is relevant to this research, given that it represents the proposition that the Armed Forces will first be in charge of safekeeping the country's internal security and second, responsible for fighting organized crime (Gobierno Federal, 2008). This became the first official declaration from a governmental entity that specifically granted authority to military corporations, beyond their responsibility for security at domestic levels.

In office, the president announced the National Campaign against crime that -through his power to deploy the entire Army- would send the Armed Forces to the streets with police-like attributions. Even, 10,000 soldiers joined the Federal Support Forces, an institution that was the strong arm of the then PFP (Regino, 2007). In the first quarter, there where resounding results: organized crime-related executions had doubled the previous year numbers. Initially, force deployment had been focused on the most vulnerable states, where there was an astonishing increase in violence (Regino, 2007).

President Felipe Calderón faced a difficult political scenario and used the security problem as a way to increase his government approval ratings. In the same way, discussion on the subject strengthened the international scenario and became an important point in the relation with the United States within multiple binational agreements. Finally, the president faced power games among political parties that, until that date, had blocked the creation of a state security policy (Astorga, 2015).

Eventually, Calderón posed his intention of improving police institutions through professionalization and through the eradication of internal corruption. However, the violence levels reached the year after taking office obscured his vision and led the decision-making process to the path of militarization that had been underway. The increase in attribution was gradual but constant. In political terms, powerful actors favored the Armed Forces. Nonetheless, towards the mid-term, results were not as expected and the international public opinion towards the military strategy was critical due to poor local police conditions and corruption (Juárez, 2016).

Based on the previous reconstruction, President Felipe Calderón issued in early 2009 the General National Public Security System Act (LGSNSP). This act, according to Article 21 of the Constitution, clearly defined the objective of "establishing the distribution of tasks and the foundations of coordination among Federations, states, Federal District and municipalities in this regard" (Article 1 of the LGSNSP) and, most importantly, with the purpose of evaluating and certifying the country's police bodies. This act stands out for defining that all the police corporations have to be civilian, disciplined and professional. It also recognized the importance of the promotion of citizen's participation and accountability of the public security institutions. Notwithstanding, results showed that the strengthening of the police at the federal, state and municipal levels was not adequate and this blocked the gradual roll-back of the Armed Forces.

Between 2009 and 2010 and because of the strong deployment, the Armed Forces were questioned over human rights matters and military jurisdiction. Nevertheless, there was military personnel integrated to the federal and local public administrations. For example, the National Defense Secretariat proposed to the Governor of Chihuahua the appointment of a retired Division General, Julián David Rivera Bretón, as Public Security Secretary and of Colonel, Alfonso Cristóbal García Melgar, as Police Municipal Director of Ciudad Juárez (Moloeznik, 2012).

In response to criticism by both national and international non-governmental organizations, Felipe Calderón justified the action taken by saying: "Only by having truly professional police officers, we can make sure that the Armed Forces are relieved from their temporary and subsidiary positions of undergoing citizen's security, without posing a danger to society" (Juárez 2016: 258).

Enrique Peña Nieto: National Gendarmerie, Military Police and the Internal Security Act

Path dependence theory shows that the route traced by Felipe Calderón's presidential term did not generate institutional blockades except when there was a moment of structural persistence. The administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto represents that phase of structural persistence. Although campaign discourse raised the reorientation of the public security strategy, governmental actions demonstrated the existence of continuity in the strategy. It is in these dynamics that the relevance of the approach stands out since these policies were, rather, the result of an existing path, backed not only by the discourse but also by the institutions, their structures and approaches.

At the beginning of his term Peña Nieto proposed the creation of a National Gendarmerie, which would be an organization different from the pf and which would consist of 40,000 military members under civilian rule (Hope, 2017). The Armed Forces showed resistance to this proposal but, allegedly for budgetary restrictions, the Gendarmerie was created in 2013 with only five thousand members under military and police instruction (Hope, 2013). In the end, the PF was maintained, the Armed Forces continued in public security operations, and the Gendarmerie became a small organization.

This new body became a division of the pf, opposite to what it was originally proposed to be: an intermediary body of military origin and identity. This plan sought to take advantage of the good image of the Armed Forces in order to build trust with society. It is important to highlight that even though this idea was altogether eliminated, upon defining the Gendarmerie as the seventh division of the PF, its training was military nonetheless (Hope, 2013). In the same way, the existence of this new security institution, in the words of the head of the Interior Secretariat (SEGOB), Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, would enable both the Army and Navy to retreat to the barracks.

Notwithstanding, it was clear that in this setting the use of the Armed Forces in tasks assigned to civilian authority presented serious threats such as the persistence of high levels of violence. Because of this, the same military organizations demanded regulation and legal certainty regarding the lack of definition of concepts such as public security. As Moloeznik (2012) points out, ever since Felipe Calderon's term, the Armed Forces started the search for an "ad hoc legal instrument that allows them to withdraw from any type of complaint or legal process" (p. 139).

This concern, addressed by the PND as a challenge to the Armed Forces, required an immediate response. It identified the necessity of having a better legal framework -specifically in internal security matters- that could provide them with certainty in its acting as a military organization, as well as for respecting human rights (Gobierno de la República, 2013).

In the PND there was a first approach to the concept of internal security as an element on its own. Particularly, it was agreed that, as the Constitution points out, the mission and purpose of the Armed Forces would be "defending the nation and contributing to its internal security" (Gobierno de la República, 2013, p. 32).

Nevertheless, multiple criticism and gaps identified in the initiatives led to the passing of the Internal Security Act, published on November 30th, 2017. This document, from which several controversies arose, maintained the established definitions and stated that internal security "responds to keep internal stability, peace and public order, and is a responsibility of the three government branches" (Cámara de Diputados, 2017, p. 50). This seemingly justified the participation of the Armed Forces and made legislators assessed their involvement, as necessary. Once the Act was approved by the Chamber of Deputies, the opposition parties condemned it strongly having identified multiple risks and vulnerabilities that were not answered, despite it being only one bill.

It is important to note that the Act would have institutionalized the Armed Forces' participation in several areas. That would have forcefully blocked all development plans in slate for police officers, in areas such as economic resources, training, and professionalization. Nevertheless, the greatest threat was that it would have replaced the police force in its function, thus creating a new panorama in which civilian authority would have been useless.

There were movements, groups and organizations that impetuously contributed to the declaration of unconstitutionality by the SCJN. The participation of the opposition in the Chamber of Deputies, with 115 votes signed against the bill, also stands out. Nonetheless, these actions could also have been in response to the political parties' narratives under political junctures. This is where the next phase of the path dependence process, called reactive sequence, begins. In this phase, actors respond to prevailing agreements through a series of predictable answers and counter-answers. This stage is specifically important because it takes the process directly to its final result (Mahoney, 2001).

The failure of the Internal Security Act sparked off the debate on the necessity of a framework that endorsed the Army day by day. However, from this particular point onwards it is necessary to highlight that even though it is not possible to have military personnel without a legal framework, creating a law that allows them to be on the streets without the necessary adjustments, favors directly the continuity of path dependence.

During Peña Nieto's government, there was a rise in the political power of the Armed Forces through the long reach of public debates and public opinion. There was also the absorption of new bodies comprised of civilians that contributed to their public security tasks. On the other hand, the declaration of unconstitutionality of the Internal Security Act made clear that it was not a measure that catered correctly to the needs and considerations of the state's own survival. Even if it was victorious as a statement in favor of strengthening public security in Mexico, it was enough to keep alive the tenure in this route.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador: National Guard

Upon being elected president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) presented his Peace and Security National Plan. This document presented an ambitious plan that ranged from the elimination of corruption and the ethic regeneration of society to the reformulation of the fight against drug trafficking and the public security arena. In relation to the country's militarization, it began by revealing that in Mexico more than 200,000 people had been the murdered and more than 37,000 had disappeared as a result of a "police and warmongering strategy" (López-Obrador, 2018, p. 10).

In the face of this scenario, the most important driving force was the public security plan, which was divided into three proposals, of which the first two are analyzed herein. Proposal number one revolved around rethinking national security and redirecting the Armed Forces, which had been worn down because of their fulfillment of tasks that were not within their jurisdiction. It also mentioned that the people's trust had decreased, a particular situation considering that in the previous administration this was a key element to maintain the status quo (López-Obrador, 2018).

That same document recognized that military forces did not have the sufficient training to prevent and investigate crimes, which seemingly explains why human rights violations have taken place. Likewise, it accepts that the military deployment has disabled the civilian public forces in the tasks of crime prevention and fighting since 2006, and also acknowledges that forty thousand elements from the pf were poorly trained and mostly fulfilled administrative tasks.

Despite this alarming diagnosis, it declared that it would be "disastrous to relieve the Armed Forces from their current activities in the public security area" (López-Obrador, 2018, p. 14). For this reason, there would be continuity in this provision taking into account Article 89 of the Constitution, favoring respect for human rights, as well as personal integrity and property. It is important to point out that as portrayed in AMLO'S Nation Project, the Armed Forces would disappear from the streets in the medium-term to make way for the National Guard, which would assume civil protection functions at a federal level on all issues (López-Obrador, 2018).

The second proposal was the formal establishment of the National Guard. In order to achieve this, it was necessary to amend Article 76 (XV) of the Constitution so that this body could be an essential tool of the Executive branch for preventing crime, safeguarding public security and fighting crime in the country. The document proposed the participation of military and navy police officers, the former PF in addition to the recruitment of civilians, specifically around 50,000 new guards (López-Obrador, 2018).

It is important to remember that President López Obrador's administration is characterized by the victory of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA, by its Spanish acronym) in the Executive power. Furthermore, it has the majority in the Federal Congress with 259 deputies and 59 senators, and the majority in 20 local congresses. This configuration shows the overwhelming power that MORENA and the president have at a national level. Nonetheless, this situation has also brought uncertainty on how this power would be used in the Mexican political scenario.

This represents the continuity of the status quo, where the Armed Forces continue to be deployed on the streets, but now with a constitutional support; that is, an institutionalization of this measure has taken place at a national level. Furthermore, in the transitory articles of the act concerning the creation of the National Guard, it is stated that in the next five years, both SEDENA and SEMAR are going to be involved in the hierarchic structure and discipline regime They will have control over the income admission tools, education, training, pro-fessionalization, promotions and benefits of the Armed Forces (DOF, 2019).

III. The National Guard: Upcoming conflicts and future challenges

With the creation of the National Guard as an intermediary civilian-military force, Mexico is debating the most profound reform of the security and national defense apparatus since the 1917 Constitution. The creation of this organization seeks to give the country an institution with a true national force. In order to contextualize the situation of security institutions, it is necessary to know specific data of their chronic fragmentation. Mexico has less than 30,000 pf officers, 36,000 Military Police members and close to 9,000 Navy police officers to serve its 130 million habitants.

The country is a federation, and as such, its 32 states and 2,458 municipalities are jointly responsible for public security. However, according to the National Diagnosis of state police officers, that was published by SEGOB, in 2017 the local government barely has half of the minimum State police of force that it should have. According to this report, the state requires at least 115,943 new police officers to reach the minimum standard of 1.8 for every one thousand habitants, totaling about 234,944 police officers. Most governors in Mexico have been highly irresponsible for not creating public security institutions with enough human, professional, equipment and training capacities in order to meet the required numbers.

The deployment of the Armed Forces in public security matters has generated an institutional trap. States have been affected by common crimes and by the violence provoked by the Mexican cartels, while governors rest in a comfort zone by continuing to use military and navy personnel in order to fulfill this security deficit.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador received a country with the highest levels of violence, corruption and impunity that have been registered probably since the Mexican Revolution at the beginning of the 20th century. According to the Institute of National Statistics and Geography (INEGI, by its Spanish acronym), in 2018 there were 36,685 murders in Mexico. As seen in Figure 3, these have been critically on the rise since the start of the 'war on drug-trafficking' in 2006. Given this, and because of the high incompetence of local governments, he wanted to accept full responsibility for the situation and proposed a militarized model of national police with legal arrest, investigation and deterrence capacities. Nevertheless, in the Senate, the opposition, scholars and civil organizations pushed the premise that the National Guard should have a civilian rule, albeit military doctrine and training.

In all the discussions, there was the issue of the country's militarization and the threat of the rise of the Armed Forces' political power, which indeed have very few checks-and-balances and management mechanisms by civilian authorities. As expected, governors and mayors prefer to have, as a mediator in the deployment of the National Guard, a civilian minister whom they could negotiate with and not an intransigent military officer when making their political petitions.

The first challenge that the National Guard is going to face is the recruitment of new cadets. Because of the infrastructure and national deployment of facilities, it would be much easier for the Army and Navy to train the new future members of the Guard with military discipline in matters of information analysis, tactical operations, the handling of firearms and the use of vehicles. The pf, through its Police Development System, would help train future national wardens supported mainly by the Scientific, Intelligence and Gendarmerie divisions. Although the number of members has been on the rise, it remains an important element for the success of national security strategies. As portrayed on Table 1, the National Defense Secretariat has deployed close to 52,000 members in 2018, a significant increase with respect to 2005 with only 32,074.

Table 1 Personnel of the National Defense Secretariat deployed in the fight against drug-trafficking and as back-up for public security, 2000-2018

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2016 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30,991 | 32,074 | 49,650 | 51,994 | 52,000 |

Source: Benítez (2019, p. 191).

The standardization of salaries and social benefits is going to generate tensions, as well as the origin of the ruling in different areas of the Guard. The doctrines, codes, languages, thinking and the organizational culture are different between the military and the police. Changing the mentality of first-generation wardens that come from different institutions is not going to be an easy task, but it is not an impossible one. The key component is going to be in the secondary laws that the Congress approves.

Everybody wins with the creation of a National Guard with a civilian rule, as was approved in Congress. The Defense and Navy Secretariat would receive the additional budget approved in 2018 for the formation of this new institution. In political and strategic terms, the Security and Citizen Protection Secretariat, under Alfonso Durazo's direction, is the winner. He is going to have a strategic role in the creation of this new organization. He will have to manage the structural power conflicts that are politically within the national security system. President López Obrador was recognized as a true leader by accepting the modifications that the political opposition, accompanied by activists and scholars, proposed.

There also remains the question of the powers that each institution has in internal security operations. As stated by Pion-Berlin (2017), the success of each operation (which in themselves are different from one another) will depend on how well-designed its institutional and operational framework is. If recruitment in the National Guard is deployed to fulfill the tasks it was trained for, then it will be easier for it to avoid collateral damage. In this sense, the institutional design of the National Guard will be key to understand and have success in its activities as a public security institution.

Nevertheless, violence and impunity will not simply end with the creation of the Guard. These are problems structural in the security and justice systems, which are currently collapsed. Mexico has poor justice institutions in the local field, with very little independence from the local power. Very few state police bodies are truly professional. The government is barely paying attention to the issue of money laundering and asset recovery. If the current trend of creating and strengthening institutions continues, it is going to take at least a decade for Mexico to have security and justice institutions that allow impunity and violence level reductions.

Finally, there are two specific challenges for Lopez Obrador's administration. The first is that in the next couple of years the National Guard should move from being a military institution towards a civilian one. The second challenge is achieving the proffessionalization and strengthening of State security organizations which should reach minimum structure and functioning standards that are actually verifiable. If this second challenge is not fulfilled, we are in danger of facing the debate of whether to employ the Armed Forces in public security matters in five years due to the incompetence of local governments and civilian authorities.

The model of the National Guard has to be a 'modernized one' as Sampo states (2019). Traditional Armed Forces are not ready to face modern threats and phenomena such as public security. Renewing its tasks can have a better impact in re-directing their activities in order to carry them out correctly. Through its deployment, this new security force has to be adapted to a civil police model, going through changes that do not necessarily represent a 180-degree turn of its capabilities. Even if the National Guard comes out as a hybrid force, there has to be reassurance that this new institution has a limited transitory model (Sampo & Troncoso, 2017 in Sampo, 2019) in order to carry out conventional and non-conventional tasks.

Using the Armed Forces in public security tasks (specifically in the fight against drug trafficking) is not something as new as it might seem, especially in countries such as Bolivia, Venezuela and Colombia. Regarding Bolivia (one of the largest cocaine producers globally), the Armed Forces work on this issue since the 1980s and currently work to back-up the logistical operations of police forces in specialized groups. In Venezuela, the change in the use of the Armed Forces increased at the end of the Cold War and now develops as a full involvement model, with the Armed Forces intervening in most of the social life in the country (Bartolomé, 2019). Finally, in Colombia the involvement can be divided roughly in two phases: between 2007-2010 and from 2012 to these days. The Armed Forces were within the framework of Plan Colombia and its main actions focused on combating guerrillas with an exponential increase of their budget (Ríos, 2019). In the current scenario of the post Peace Deal, the situation is on a 'limbo' because of the uncertainty of their role in this process.

Conclusions

The participation of the Mexican Armed Forces in security matters is not a new trend, as some critics might say. On the contrary, their actions go back about 80 years, which has given rise to chronic path dependence. In the same way, the methodology used in this research allowed for a historical approach that contributed to identifying a trend -the militarization of public security in Mexico- as well as to the understanding of its perpetuation and of the institutional changes that favored this scenario.

In addition to this civilian dependence on military action for public security issues, it is important to take into consideration that the Mexican Armed Forces have strongly benefited from the extraordinary human, economic, technological and even international cooperation resources since 2006. These incentives have generated dynamics between civilians and the military that nowadays perpetuate the inertia, and which has resulted in the creation of an organization such as the National Guard.

The analysis of results over time also allows for identifying that rollback costs are remarkably high, particularly because the immediate return of the military to the barracks is impossible. There are no police institutions with the sufficient capacity for countering the violence crisis. This scenario generates uncertainty while suggesting an overwhelming rise of insecurity and violence levels. Likewise, it points to a conflict amidst the pursuit of justice in Mexico, because the attributions and duties have blurred. This has resulted in a dangerous perception that the civilian authorities appear to be unnecessary.

The fight for power and resources in the public security sector will continue between civilian and military institutions. It is still too early to define who will be the real winners after the creation of the National Guard.