Introduction

During the 19th century, the Armed Forces (AF) participated in the independence struggles in South America. Governments passed to civilian elites, and new democracies were born on the American continent. However, the AF has never wholly abandoned its power. In the 20th century, some military intervention took place in all countries in the region. Years or decades passed before power returned to civilian rulers. In the last years of the 21st century, something has changed; since 2001, several countries have faced economic, political, or social crises without the military appearing as a solution. The prospect of a military coup is no longer an option; we believe that part of this is due to civil and armed relations’ maturity.

The position of the armed institutions is crucial in this scenario because, even though they have military power (a monopoly on violence), they have not used it to their advantage, remaining subordinate to civilian authority. Thus, we ask: How did civilian control over the military process start the loss of autonomy of the South American Armed Forces? To answer this question, we proposed an AF Autonomy Index based on variables indicating the South American AF’s level of independence / civil control. The study is based on theoretical references and empirical elements. The literature review supports the theoretical basis and information mapping to the practical structure. The background of this work is the classic question of civilian control over the military (Burk, 2002; Kenwick, 2020); looking beyond official regulations and documents, a small part of the history of the Armed Forces’ participation in the region’s governments until 2017.

The text has six sections. The first section analyzes the AF’s history in forming South American nations with an internal focus. The second section observes the role of the AF in the interstate context, considering the perceptions of conflict in the region and focusing on “long peace” and “violent peace” to seek an understanding of the permanence of the external defense function. The third section discusses military regimes and their influence on military autonomy, analyzing the transition process. The fourth section focuses on civilian control over the military institutions, where we observe and compare the level of defense autonomy or degree of civilian control in the South American Armed Forces. In the fifth section, we analyze the data collected in the previous sections, creating an overview of the region. Finally, the sixth section brings the conclusions.

Armed forces in the formation of south american nations

States have always been linked to armed organizations and have evolved in parallel. This vision is shared by some authors, such as Domingos Neto (2014), Jerry Dávila (2013), Carlos Fico (2008), and Héctor Saint-Pierre (2008). According to Domingos Neto (2014, p. 206), every state establishes a historical connection with its armed organization. South America is no exception; however, it possesses unique characteristics.

Since the origin of the flaming American nations, during almost the entire 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the armed forces have played a central role in the political configuration of Latin America. This recent role of the military was partly due to the warlike exercise of liberating the metropolises, but also because armies were one of the first structures of recent states to emerge with autonomy (Saint-Pierre, 2008, p. 15).

According to Saint-Pierre, the origins of the armed forces in South American states can be traced back to the struggles for independence. This historical role allowed them to be close to the decision-making circles of the founding states, having the autonomy to organize themselves according to their demands and rules. As a result, they evolved into state institutions with distinctive cultures, setting them apart from other entities through their values, traditions, hierarchical system, and discipline. It is important to note that each country exhibited its own dynamics, where civil and military actors established their relationship with the formation and control of the state.

While essential, this detailed history of civil-military relations in each country differs from this text’s purpose. For those who want to go deeper into the topic, we recommend reading some works: (i) for an overview, Jerry Dávila (2013), Carlos Fico et al., (2008), David Pion-Berlin (2008, 2009, 2010, 2016); for Argentina, Gabriela Aguila (2008); for Brazil, Daniel Aarão Reis (2014), Héctor Luis Saint-Pierre (2008), Manoel Domingos Neto (2014), Juliano da Silva Cortinhas and Marina Gisela Vitelli (2021) e Vitelli (2022); for Chile, Luis Hernán Errázuriz (2009); for Ecuador, Juan Paz y Miño (2006); for Uruguay, Enrique Serra Padrós (2005); for Bolivia, James Dunkerley (2003); for Paraguay, José Carlos Rodriguez (1991); for Venezuela, Fernando Coronil Imber (2016) and Deborah Norden (2021); and, finally, for Peru, Cecilia Méndez (2006).

On the other hand, it is logical that, as protagonists in the formation of the South American States, the AF have reached a level of autonomy linked to their history that can be perceived from different points of view. Martin says that “the struggle for independence in the Spanish colonies was carried out by armies without any kind of civilian control. Thus, once independence was achieved, the generals became the new rulers” (2006, p. 152). It was the military elites who led the States in their first years of republican life, and the presence of civilian leaders was guaranteed from the second until the third presidential term (see Table N° 01). Martin attributes the link of armies to the State to his Spanish heritage.

Table N° 01. - Civilians and military commanding the South American nations in the independence process.

| Country | Independence* | 1st Governor | Names of the first presidents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil | Militar | |||

| Argentina | 1816 | X | Bernardino Rivadavia | |

| Bolivia | 1825 | X | Simón Bolívar; Antonio José de Sucre Alcalá | |

| Brazil | 1822/1889 | X | Don Pedro I (Emperor); Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca | |

| Chile | 1818 | X | Bernardo O'Higgins; Manuel Blanco Encalada | |

| Colombia | 1819 | X | Francisco de Paula Santander | |

| Ecuador | 1822 | X | Juan José Flores | |

| Paraguay | 1811 | X | Fulgencio Yegros; José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia | |

| Venezuela | 1811 | X | José Antonio Páez | |

| Uruguay | 1828 | X | José Fructuoso Rivera | |

| Peru | 1821 | X | José de San Martín | |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

* It was decided to indicate the final years of the wars of independence and transition to the Republic.

Likewise, the construction of national identity in South America was closely intertwined with the participation of armies in the wars of independence. This active involvement granted them the title of independent managers or founders of the Fatherland, according to Centeno:

The heroism of war is especially appropriate for the elaboration and consecration by States. (...) Wars, whether victorious or not, are also moments of national unity when the collective destiny of a nation, at least theoretically, nullifies individualist imperatives. Celebrated in stone and paper, acts of war remind the people to whom their loyalty belongs. (2014, p. 376)

During the wars of independence against the colonial powers, the struggle involved not only economic elites and the general population but also prominently featured the leadership of military figures. In South America, only Uruguay had no military person in charge of the independence process. Brazil had an emperor who was also the military chief and a military man during the Proclamation of the Republic.

One of the armies’ missions was to carry out possession and presence throughout the national territory and at the borders, working with other actors for national development. Thus, barracks were created in parallel with the installation of farmers (Steiman, 2002, p. 2), traders, telegraph lines, roads, and later airstrips. This participation in the planning, organization, and control of the territory made the AF an active entity in the decision-making process in different parts of the region: “On the other hand, while waging the war of independence against the metropolises, armies were the main tool for building national decision-making units when facing armed groups from the centripetal movements within the national territory” (Saint-Pierre, 2008, p. 15).

Thus, the decision-making process considered the wishes of the military elites, which constituted an active part in the actions of the state and were armed labor, organized and deployed throughout the national territory to combat separatist movements and defend the territory, while at the same time that collaborating with local civilian powers. The AF had a presence both in the capitals and areas far from the capitals, consolidating a role and an image with the populations and facilitating their autonomy and political power.

The consolidation of armies in South America is also due to the relations maintained between the countries’ AF and the presence of foreign military missions, notably France and Germany, which collaborated in the institutional consolidation of the armed organizations.

Armed Forces and Regional Conflicts

Once independence was achieved, the AF’s role was to protect sovereignty and the national territory, sometimes conquering new territories. In the post-conflict phase of independence, the continent’s internal conflicts promoted the formation of South American borders. In this way, the boundaries of the former Spanish viceroyalties and the Brazilian colony took on their current form.

The great wars of the period were the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), the War of the Triple Alliance (or War of Paraguay) (1864-1870), and the Chaco War (1932-1935). However, other wars that have caused territorial gains and losses have occurred, which is essential for the involved countries. The three wars mentioned were long lasting, involved large contingents, and had extensive theaters of operations. The absence of other wars of this magnitude, especially in comparison with European and world wars, generated a theory believed by certain researchers who affirm that South America was a relatively peaceful continent, in a line of interpretation known as “long peace” (Sposito & Ludwig, 2021).

Arguments based on this interpretation question the necessity of maintaining Armed Forces (AF) in South American countries due to the limited occurrence of interstate conflicts and the belief that the implicit cost of war outweighs the potential benefits for any country involved (Kacowicz 1998, Centeno 2014, Martin 2006, Krujit and Koonings 2002).

However, knowing that interstate clashes have their particularities in the region, a second approach to the region’s conflicts, called “violent peace”, is justified in interstate conflicts and tensions, where the use of force and/or demonstration of it is recurrent. David Mares maintains this position by stating that “the statement that Latin America is the most peaceful region in the world is empirically incorrect” (2001).

Going deeper into regional history is good for highlighting a series of conflicts between South American countries and foreign nations. They were not long wars, nor did they have a high economy or cost of living, but they mobilized nations and motivated nationalist feelings; at the center of events were politicians and soldiers.

The countries of South America are states with common roots that have experienced the same influences over time that suffer from similar problems (political, social, and economic) that may have influenced them to adopt a different view of how to perceive and respond to conflicts. Thus, because they do not have the necessary resources that a total war implies, they developed the Armed Forces according to their needs (Franchi et al., 2017, p. 19).

Previous studies established that conflicts in South America are in place and that States, as expressed in their constitutions, assign external security as a priority to be carried out by their AF. These moments of interstate tension would grant more power and greater autonomy to the AF since the nation’s interests or territory were threatened. Until 1995, with the end of the Cenepa War between Peru and Ecuador, several tensions and battles had taken place in South America.

In the 21st century, interstate conflicts remain latent. However, there is growing concern about emerging threats, such as organized crime, drug trafficking, and terrorism, which have the potential to generate reasons for tensions and even escalate into interstate conflicts. (Franchi & Jiménez, 2021, p. 19).

A concrete example can be seen in the case of Angostura in 2008, involving Ecuador and Colombia. During a military operation targeting the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) leaders, the Colombian Armed Forces violated Ecuador’s airspace with aircraft. They conducted a bombing raid on a FARC camp located within Ecuadorian territory. The episode led to the rupture of diplomatic relations between the two countries (Marcella, 2008; Montúfar, 2008).

Mares states, “Transnational criminal organizations are almost indestructible, as they adapt quickly to changing conditions, form coalitions, and actually corrupt regions where state authority is absent” (2006, p. 143). The capacity of the National Police to effectively combat international criminal organizations is often limited, necessitating military support, particularly in border regions. Emerging threats to the security of states domestically are present in almost all countries. South America is aware of its existence, as shown in the new scenarios considered by bodies such as the United Nations and the Organization of American States.

The transition from military regimes to Democratic regimes

In the 1950s, several South American countries had military governments that lasted until the late 1970s and mid-1980s: “As recently as 1987, almost half of the region lived under military or military-backed rule” (Croissant, 2004, p. 357). The presidents were active military personnel in the Armed Forces and had not come to power through popular elections but through coups d’état. The end of the Cold War brought about a significant shift in the international context, encouraging democratic processes and the loss of military control over executive power. As Rial states about the democratization processes in Latin America, countries “were led to regain or create a certain degree of control by the legitimately constituted political authority over matters of defense and military institutions” (2008, p. 71).

However, even though most South American countries were going through a period in which their AF returned to barracks after several years of military rule, it should be noted that in the early 1980s, there were nascent state organizations that had not yet consolidated. Conversely, the AF was an organized and structured institution capable of supporting and maintaining a presence throughout the entire national territory. According to D’Araújo’s comment after the return of the AF to the barracks, “[...] in several countries, the use of the AF has not been ruled out as a factor of national development or as a balance in the political game” (2010, p. 58). The logic would be to take advantage of the installed and operational capacity offered by the AF without losing sight of the process of untying the AF to the decision-making process of the new political elites.

The Armed Forces, as a product of the experiences developed during the period of military governments and the early stages of transition, have evolved into a moderate institution firmly committed to upholding the constitutional mandate. Over time, Ministries of Defense were created, headed mainly by civilians, allowing governments to control the AF ratifying the importance of civil power over the AF.

In 1995, the first conference of defense ministers, which took place in Williamsburg (USA) (CMDA, 2019), emphasized as a cardinal principle that “our armed forces should be subordinated to an authority with democratic control and within the limits of national constitutions, and that they should respect human rights” (Rial, 2008, p. 72). Since then, thirteen conferences have been held until 2018, in which the principles established in Williamsburg were promoted and experiences from the different ministries’ agendas were exchanged.

However, their role remained significant after the Armed Forces (AF) returned to the barracks. They continued to deploy their contingents for various internal activities beyond territorial defense, which led to new roles for these actors. Additionally, countries have been grappling with public security problems, as highlighted by Pion-Berlin: (...) In recent years, the growing problems of public security and development have led governments to increasingly turn to the military to fight drug trafficking, control delinquency, or assist with social programs (Pion-Berlin, 2008, p. 50).

Except for Argentina and Uruguay, it could be said that the transition from military to civilian governments in South America did not affect the organizational structures of the AF, as it was a process agreed upon between the political and military elites of that time, avoiding the weakening of the armed institution s image.

The notable trend in this century has been the gradual loss of autonomy by the Armed Forces (AF). This shift can be attributed to the processes initiated during the re-democratization period, including the establishment of defense ministries. These developments have contributed to a new scenario characterized by a restructured framework of civil-military relations.

Civilian control over the South American Armed Forces and the loss of autonomy

After three decades of military governments, civilian control over the defense sector was gradually organized. “Latin America has achieved an effective subordination of the military to civilian power. (...), but it does not mean that the Armed Forces have definitely withdrawn to the barracks” (Pion-Berlin, 2008, p. 50). However, the perception is that they will hardly return to occupy the leadership of the States in an authoritarian way due to the political costs of such actions:

At the beginning of the 21st century, civil-military relations in Latin America were more stable, and the Armed Forces are more politically fragile than at any other time in history. In most countries in the region, armies have lost size, resources, influence and importance. (...)

In the past, crises of this type would have been resolved through military intervention and the establishment of an authoritarian regime, but not anymore. Although some presidents were removed from office before completing their term, those responsible were not Generals, but legislators, protesters, or the force of events. (Pion-Berlin, 2008, p. 50-51)

Currently, the legislation regulates the AF’s missions and competencies, and the training and development institutes for officers and troops emphasize studies to improve civil-military relations and the rule of law (Beliakova, 2021). For South America, it is clear that “today’s military is learning to live under the rules of democratic systems” (Pion-Berlin, 2008, p. 51). For Pion-Berlin, the AF demonstrated political maturity and kept themselves out of political decisions, allowing them to be taken in compliance with constitutions and other rules. This may also have occurred due to a loss of military autonomy in the face of processes of re-democratization and systems of subordination of the military to civilian power.

Integration between South American countries has increased (Marini, 2019). Peace agreements and border recognition, cooperation agreements, both bilateral and multilateral, and the creation of economic blocs such as the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), the Andean Community of Nations (CAN), and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) are some examples (Martinez & Lyra, 2018). These initiatives contribute to regional stability in civil and military terms (Marcella, 2008). The South American Defense Council (CDS), the Center for Strategic Defense Studies (CEED), and the South American Defense School (ESUDE) aimed to build a regional defense identity and consolidate peace as a fundamental basis for the development and strengthening of defense cooperation (Briceño; Hoffmann, 2015; Mijares, 2018). The last years’ face-to-face elections have transformed the region’s political situation, generating a misalignment with the political proposals that created UNASUR, which caused its collapse (Rodrigues & Santos, 2020; Moussallem, 2021).

In this context, to systematize and compare the level of military autonomy and the subordination to state structures (civilian control), six variables were researched in ten South American countries, seeking to formulate an “autonomy index,” which later guided the analysis of the collected data. The Autonomy Index aims to determine whether the AF has been affected by civil control over the Armed Forces, or, on the contrary, how autonomous these institutions still are.

The variables are: (1) the country has a Ministry of Defense (md); (2) the Minister of Defense is civilian or military; (3) there is a Military Justice System; (4) there are White Papers; (5) Armed Forces, and participation in Public Security activities; and (6) participation in subsidiary activities. Table No. 02 shows the proposal codex, where we can see how each variable is interpreted, and some additional references support it.

Table No 02. - The Variable Codex

| Variable | Interpretation/ References | Score |

|---|---|---|

| (1) The country has a Ministry of Defense (md) | Show the country has a state structure necessary to the subordination of the military to the civilian power, at the same time, create a distance from the executive power. (Pion-Berlin, 2008; 2009) (Pion-Berlin; Martinez, 2017) (Amorim; Accorsi, 2020). | Have +1 |

| (2) The Minister of Defense is a civilian or military | A civil minister will be more in line with political (civil) demands than with military demands. It is an important part of civilian control the minister gets involved properly in defense matters. A military minister, without a political background, will be more attentive to the daily demands of the Armed Forces and may not collaborate with involving civilians in decisions about planning national defense policies. (Lima; Silva; Rudzit, 2020) (Amorim; Accorsi, 2020). | Civilian Ministry +1 Civilian/Military 0 Military -1 |

| (3) There is a Military justice System* | The fact that there is no military ustice system and all crimes committed by the military are tried in civil courts shows total civilian control over the military. The existence of military justice guarantees a degree of autonomy for the military. The autonomy varies according to each country and the scope of its military justice (Pion-Berlin, 2010) (Pion-Berlin; Martinez, 2017). | Have -1 Don't have +1 |

| (4) White Papers | White papers have a characteristic of transparency in showing the structure, means, and planning of a country's AF. This is good for foreign policy with neighbors and goes in the opposite direction to the teachings of pure military strategy (since Sun Tzu) that would induce to hide their strengths and potential from potential enemies while seeking to know the strengths of their opponents (Amorim; Accorsi, 2020). | Have +1 Don't Have -1 |

| (5) Armed Forces and participation in Public Security activities | It shows the participation of the Armed Forces in actions aimed at public safety, which increases the population's sense of security in general, despite some of these populations being in conflict spaces - Black Spots - and therefore divided. (Mendonça; Franchi, 2021) (Heinecken, 2014) (Dammer, 2021) (Noriega, Velarde, 2020) (Pion-Berlin; Martínez, 2017 (Succi J.; Saint-Pierre, H., 2020). | Do-1 Don't do+1 |

| (6) Participation in subsidiary activities | It shows the participation of the Armed Forces in subsidiary activities that generate a positive image of the Forces (In general, these are actions that directly collaborate with the civilian population, such as: actions in natural disasters, provision of medical care for needy populations, humanitarian operations) (Moncayo, 2014). | Do-1 Don't do+1 |

Notes: * The central point is not to analyze the degree of military justice or the range of participation in public security activity, but its simple existence or not. A comparison between the systems of laws that the South American military is in is a topic for another article.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

As can be seen in Table N° 02, the variables were taken from the relevant bibliography. The scoring system defines the value of (1) when the variables reflect civilian control or one less (-1) when the variables reflect AF’s autonomy. Thus, six (6) would indicate total civilian control over the AF. At the same time, minus six (-6) corresponds to total AF’s autonomy when the military class has the power to make decisions over the civilian government, or they are the executive and make their own rules.

To collect data on the variables, electronic pages and bibliographies on the creation of (i) Ministries of Defense and the (ii) civil or military status of ministers were used; (iii) the White Papers and other documents that guide defense policies; the existence or not of (iv) a Military Justice System and the laws and constitutions of these countries connected with justice processes; (v) participation in public security activities; and (vi) participation in subsidiary activities. The results are shown in Table N° 03.

Table N° 03. - Data for the Autonomy / Civilian Control Index

| N° | Country | Ministry of Defense (creation) | Minister of Defense | Military Justice System | White Book | The Army participates in activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Security | Subsidiaries | ||||||

| 1 | Argentina | 1954 | Civil | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Brazil | 1999 | Civil/Military* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Chile | 1932 | Civil | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Bolivia | 1826 | Civil/Military** | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Uruguay | 1933 | Civil | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Paraguay | 1943 | Civil/Military** | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Peru | 1987 | Civil/Military** | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Ecuador | 1935 | Civil/Military** | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Colombia | 1965 | Civil/Military*** | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Venezuela | 1946 | Military | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

* Brazil had only civilian ministers until General Silva and Luna arrived at the post.

** Civil / Military is indicated when countries had two or more military ministers in the 21st century.

*** Colombia had only one military minister, General Freddy Padilla De León (May 23, 2008, until August 2009); all the others were civilians.

Source: elaborated by the authors, based on each country's Ministry of Defense websites.

The results of Table N° 03 and the bibliography helped construct Table N° 04, which presents data from the ten countries in South America. It is observed that all countries participate in subsidiary activities and public security, reflecting a greater autonomy of the AF due to the dependence of some States on their participation in domestic non-war actions (Assad, 2018; Jiménez; Franchi, 2020). Contrarily, the presence of the Ministry of Defense is considered a crucial element in the overall process of strengthening democracy (Pacheco, 2010, p. 27). As an institution responsible for managing defense policies in all countries and being governed by civilian ministers, the existence of such ministries reflects the impact of the ongoing process to reduce the autonomy of the Armed Forces. It places them under civilian rules and restrictions. However, it is worth noting that some authors argue that the complete consolidation of Ministries of Defense has not yet been achieved.:

Table N° 04. - Index of Autonomy / Civilian Control of the Armed Forceso

| • | Country | Period of Military Governments | Ministry of Defense | Minister of Defense | Military Justice System | Hite Book | Participation in Public Security | Participation in subsidiary activities | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Argentina | 1976-1983 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 2 |

| 2 | Brazil | 1964-1985 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

| 3 | Chile | 1973-1990 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 0 |

| 4 | Bolivia | 1964-1978 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

| 5 | Uruguay | 1972-1985 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -2 |

| 6 | Paraguay | 1954-1989 | 1 | 0 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -3 |

| 7 | Peru | 1968-1979 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

| 8 | Ecuador | 1972-1979 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 1 |

| 9 | Colombia | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | |

| 10 | Venezuela | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -4 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

This historical deficit, which gave excessive power to the military in a democracy, is evident, for example, in the perennial fragility of the Ministries of Defense. These institutions are unable to complete their function: conducting defense, outlining threats, missions, and objectives (CELS, 2008, p. 80).

However, we believe that the presence of these ministries is part of civilian control over the defense sector process and that a second step was taken when the direction of these ministries started being held by civilians.

In the context of military justice, it is observed that nearly all nations have a military justice system, except for Argentina and Ecuador, where civilian entities try members of the Armed Forces. In other South American countries, a distinct military justice system exists. However, determining the exact extent of responsibility and the types of crimes tried within each system proved challenging. For instance, in Brazil, crimes against life are typically judged by civilian courts. However, if the military element is involved in executing an executive order, they are subject to the jurisdiction of military justice (Ribeiro, 2019).

As previously mentioned, the index analysis indicates that Argentina demonstrates the highest civilian control over the Armed Forces, scoring two (2) on the index. This is primarily attributed to the presence of the Ministry of Defense, headed by a civilian Minister, and the White Paper, which promotes transparency by making defense policies publicly accessible. Additionally, the military justice system has been eliminated in Argentina. However, it is essential to note that the Argentine AF retains a degree of autonomy in its participation in public security and subsidiary activities. Ecuador follows closely behind, with a score of one (1) on the index, indicating a relatively high level of civilian control over the AF.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Venezuela stands out as the country with the highest level of autonomy in the region, receiving a score of minus four (-4) on the index. While Venezuela does have a Ministry of Defense, reflecting some semblance of civilian control over the Armed Forces, it is worth noting that the Minister of Defense is a military officer. Additionally, Venezuela lacks a White Paper that would provide transparency in defense policies. The country maintains a military justice system and actively participates in internal security and subsidiary activities. It is essential to highlight the observation made by Alda (2008, p. 14) that Venezuela exhibits a process of societal militarization and politicization of the Armed Forces.

Following Venezuela, Paraguay ranks with a score of minus three (-3) on the index. It does not have a White Paper; it has a military justice system and participates in the country’s internal security and subsidiary activities. Then, Uruguay with a score of minus two (-2). Although most of the variables reflect the autonomy of its AF, it has a Ministry of Defense with a civilian minister. In the case of Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia, they all have a score of minus one (-1). These countries have had civilian and military authorities conducting the Ministry of Defense in recent years. Under a central civilian government, this alternation of civilian and military ministers does not allow much control.

Chile stands out as a country with equal civilian control and autonomy, as reflected by a zero index (0). The military justice system (more autonomy) and other indicators determined the balance between civilian control and autonomy.

From the analysis of Table N° 04, we can conclude that there have been advances in civilian control over military institutions in South America since the democratization process. Although the AF still carries out internal interventions, they are under the civilian aegis. Pion-Berlin comments: “The Latin American military engaged in numerous functions, but they did so at the request, not against, of democratically elected officials” (2008, p. 53). In the words of Mathias, Guzzi, and Giannini, “It is no longer the military that threatens democracy” (2008, p. 84). From the above, we can say that most South American countries are reaching a point of balance between the autonomy of the AF and the process of civilian defense control.

Discussion

AF in South America has particularities that must be considered. The armies participated in the independence and construction of nation-states, and they intervened throughout the republican life in the decision-making processes, together with the political elites. Besides, the close relationship with power strengthened and maintained their autonomy. The autonomy of the AF can be attributed to specific weaknesses in the States institutional structures but also to the internal characteristics configuring them as permanent and national institutions. Its hierarchical structure and values created a solid organization.

Military strength provides the structure (in conjunction with norms, institutions, and relationships) which helps to promote a minimum degree of order. Metaphorically, military power provides a degree of security in the order that oxygen is for breathing: little perceived until it becomes scarce (Nye, 2012, p. 77).

Considering the perspective of the Armed Forces and their perception of their role in society, it is crucial to recognize that they are influenced not only by constitutional mandates but also by societal perceptions and expectations (Mares, 2014, p. 93). This premise is closely linked to the favorable acceptance of the military institution in South America, particularly regarding its effectiveness in crisis resolution, as evidenced by the Latin Barometer.

Mares (2014) and Alda (2008) emphasize the unlikelihood of military regimes. “In Latin America, military subordination to civil power is a fact, and, currently, the possibility of a military coup is unthinkable” (Alda, 2008, p. 1). However, Mares does not rule out the likelihood of moderate blows demanded by the people in the face of political crises.

(...) in Latin barometer surveys, a third of the respondents indicate that they will not support military governments. However, considering that a moderate coup is not planned to establish a military government and can be expected to quickly hand over the government to new civilian leaders, the question is a misleading indication of the likelihood of a coup (Mares, 2014, p. 98).

The States’ resources are limited; AF has the infrastructure, organization, and logistical development at the national level, allowing immediate response to different crises. It is something that the government notices.

Thus, in some cases, whether due to institutional deficiency, the urgency of the electoral agenda, the fatigue of democracy or even the lack of preparation of civilians to exercise political leadership in the areas of public security and defense, the governments of the region were, more continuously and in a greater variety of missions, using its Armed Forces as the only institution available, efficient, and reliable. (Saint-Pierre & Donadelli, 2016, p. 89).

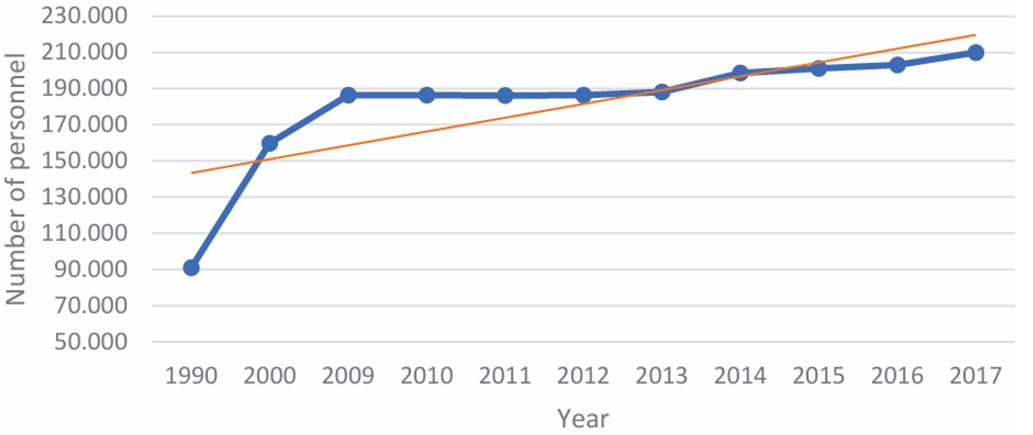

Contrasting the information presented with the analysis of the evolution of the number of military personnel from 1989 to 2017 (refer to Graph N° 1), it becomes apparent that there has been no decline in the size of military personnel.

Graph N° 01 shows the average number of personnel in the ten countries of South America from 1989 to 2017. The number of personnel has increased. In 1990, the average number of military personnel in the region was around 90 thousand per country; from 1990 to 2009, there was a growth of 105%, mainly caused by the increases in Brazil and Colombia. Between 2009 and 2013, the increment was imperceptible. It was resumed in 2014, with a rise of 5.59%. In 2015, there was notable growth in the region, reaching an average number of 210,000 men at the end of 2017.

A phenomenon observed in countries under civilian authorities that head the Defense portfolio is that they are professionals with little experience and knowledge in Defense studies (Winand & Saint-Pierre, 2007; Carvalho, 2006). However, they are considered skilled in political conduct, as stated by Pion-Berlin, who says that “Heads of state and their civilian ministers often lack the necessary preparation and expertise to engage in meaningful debates or provide effective leadership in matters concerning defense readiness, force deployment, objectives, strategy, or doctrine.” (2008, p. 58). In this sense, balancing defense knowledge and political skill is essential.

Based on the analysis conducted, it is evident that South American countries have balanced civilian control over defense matters and the necessary autonomy that the AF should maintain as an institution.

When we consider the participation of the AF in public security operations, in subsidiary activities, as well as when we observe the problems of governance in each of the countries, “the surprising thing is that, despite this, the subordination of the military power to civilians are not in danger, at least in the short term” (Pion-Berlin, 2008, p. 50). In the same vein, Alda analyzed that “Considering the AF missions and the risks of militarization existing in carrying them out, it can be said that military autonomy is not considered a problem to be eradicated or as a problem in itself” (2008, p. 14).

From these perspectives, it can be said that the autonomy of military organizations -which is vital for them to function as hierarchical and disciplined institutions- contrary to posing a threat to the State supports it (Vitelli, 2018). It is important to acknowledge that certain violent actors possess more strength and capabilities in many countries than the regular police forces, who are typically responsible for dealing with such threats. As a result, the Armed Forces are often called upon to address these types of issues, whether in a more permanent or sporadic scenario. The decision to involve the Armed Forces in such situations depends on the national legislation (Paim, 2022; Jimenez, Franchi, 2020).

However, some authors state that any AF employment in activities other than external defense constitutes a threat to democracy since this goes against the creation of spaces for AF autonomy (Alda, 2008; Alda, 2012; CELS, 2008; López, 2007; Pion-Berlin, 2008; Saint-Pierre, 2008; Jenne, Martinez, 2021). On the other hand, in the long existence of armies, they have learned to develop new capabilities, and today, they carry out numerous additional activities, including external ones linked to international bodies.

In the international context, the use of AF in Peacekeeping Operations (peace enforcement, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding operations) is part of the political game of National States in search of greater visibility on the international stage (Vaz, 2022). These missions contribute to training troops and improving their operational capacity (Pinheiro et al., 2016, p. 17).

Except for Venezuela and the small countries of Guianas Plateau (French Guiana, Guiana, and Suriname), all other states in South America are contributors to un peacekeeping operations. Its troops operate in different types of operations, such as humanitarian operations (such as Acolhida Operation in Roraima State, where the Brazilian Armed Forces, with other state agencies and NGOS, work in attention to Venezuelan migrants) (Rocha et al., 2022).

Likewise, in peacebuilding operations, military contingents from different countries play a crucial role in reconstructing the infrastructure of the affected countries, such as Brazil, Chile, and Ecuador, during the road reconstruction in Haiti. Indeed, in addition to peacebuilding operations, the AF are involved in peace enforcement operations. Examples such as the Brazilian operations in the favelas of Alemão and Maré complex, as well as the Colombian Armed Forces’ efforts against FARC dissidents, highlight the utilization of the Armed Forces in addressing security challenges in specific areas known as Black Spots (Mendonça, Franchi, 2021).

It is important to note that “There is, in the region, a certain convergence in the perception that the military should not return to power and that there is no project, by the military institution in general, to directly occupy government functions” (D’Araujo, 2010, p.39). This equilibrium point relies on two essential factors: a solid civil conviction to exercise control over the Armed Forces and their subordination to civil power, as stated by Pion-Berlin:

The expansion of roles did not lead to greater military autonomy, neither in Brazil nor in Argentina, where the presidents obtained the help of the military to put a stop to crime linked to drugs and to distribute food and health services [...]. In turn, Colombian President Álvaro Uribe maintains civilian control over the military considering their strong intervention in the fight against the guerrillas (Pion-Berlin, 2008, p. 56).

The institutional autonomy of the AF is essential for them to survive, considering their particularities, like military culture and structure (Pion-Berlin,1992). Regarding the pertinence and the possibility of using the AF in Public Security activities:

[...] Whenever there is a legal norm that regulates and limits their political use, allowing the consensus of the State’s powers, under the command of the President, emphasizing that the monopoly of force is used in an ethical, coherent and responsible manner for the benefit of State. The scarce resources available to countries make it necessary to optimize their employment, without undoing their raison d’être (Jiménez, 2015, p. 132).

Finally, according to Travis (2018), the roles and functions of the Armed Forces encompass various aspects of national security. Establishing a closer relationship between civil society organizations and the military becomes crucial to address this. This relationship should foster the study of Security and Defense topics, enabling the development of civilian specialists in defense. This approach aims to address the acknowledged deficit in this area, as recognized by academics such as Pion-Berlin (2008), RIAL (2008), and CELS (2008). Ultimately, this will enable the administration of the armed institution with a deeper understanding of its complexities and requirements.

Conclusions

A link with the existence and evolution of the AF marks the development of the South American States. From the analysis, it was observed that the levels of military autonomy and the degree of subordination to the norms of the democratic system of the Armed Forces in South American countries tend to balance. Generally, the AF maintains a degree of autonomy, and civilian control over the defense sector guarantees their subordination to civilian powers.

Defense Ministries, most of which are under civilian control, is a strong point within the civilian control over the barracks. Military Justice systems and the presence of White Papers are the indicators with the most significant variability; however, the scope and efficiency of Military Justice require specific research. White papers provide transparency with society and neighboring countries, highlighting the increase in dialogue between civilians and the military (OEA, 2003, p. 1).

The Ministries of Defense are predominantly led by civilian authorities, highlighting the subordination and political nature of the position rather than emphasizing the specific knowledge necessary for the adequate performance of defense functions. However, politicians and civilian society must be more interested in and become more involved in defense subjects. By doing so, they can actively participate in developing the nations primary defense policy.

As for the existence of specific state weaknesses and the use of the AF in non-war actions within countries, such actions would have occurred on the demands of civil authorities, indirectly favoring the acceptance of the AF as part of the solution to state problems.

Finally, it is important to note that at the end of the 20th century, moving towards the end of the second decade of the 21st century, the Armed Forces in South American countries have generally remained detached from the political oscillations of executive power, except for the Venezuela case. Likewise, in the recent past, there have been no military coups where armed forces gained control over their respective nations. This shows us the maturity level of civil and military relations. Although it still must move in this direction, South America seems to have found a way to balance military autonomy with civilian control of the Armed Forces.