Introduction

A simple finding, perhaps grounded in common sense, would suggest that economically more developed countries, characterized by higher degree of urbanization, formal education and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), would naturally gravitate towards democratic governance. This is because all these elements directly and indirectly represent significant social advances to society and would be conditional on the fight against authoritarian ideas. Consequently, they favor the advancement of socioeconomic indicators, including per capita income. Hence, states facing the opposite situation - marked by a low degree of socioeconomic development compounded by structural issues - would fatally be placed in the ranking of non-democratic nations.

The literature underscores that this hypothesis is a generic and lacks empirical ballast, as the historical trajectory of states is anything but linear (Lipset, 1967). Therefore, it is reasonable to affirm that there are more complex issues involving, for example, the acting of various actors - such as the Parliament, international organizations, and NGOS - for the process of development and production of democracies. These perspectives are not necessarily linked to the conventional theories of modernization.

The main objective of this article is to analyze the situation of Haiti by examining the literature related to concepts of development and democracy. We aim to establish conections between periods of political instability and their potential impacts on development. The guiding hypothesis for this analysis suggests that the United Nations peacekeeping operations, tipically implemented during moments of democratic rupture, contribute to improving the levels of development in the affected states, thereby influencing elementary indicator necessary for addressing structural problems.

From a methodological perspective, this article conducts a comprehensive literature review on the theoretical discourse surronding development and democracy, as well as on UN-sponsored peacekeeping operations . Subsequently, the study relies on support from the Polity IV indicators sourced from the Freedom House and the World Bank. In order to analyze, respectively, the periods of failures in the democratic regime and the behavior of the GDP and per capita income variables. This analysis was adopted based on the qualitative method of case study, because it takes as object specifically Haiti's peacekeeping operation. The objective is to derive explanations that may be applicable to similar scenarios - in order to confer external validity (Yin, 2008, p. 58).

This article is divided into three sections. In the first section, we discuss the evolution of the theoretical debate surrounding the relationship between democracy and development, beginning with the tradition initiated by Lipset in the 1960s and continued by researchers such as Przeworski, Limongi and Boix & Stokes. In the second section, we analyze the un peacekeeping operations, from a case study of Haiti, the first independent republic of the Americas, which has undergone numerous democratic ruptures in its history and which today faces chronic problems to overcome its socioeconomic problems.

In the third stage, we employ readings from the Polity IV and the World Bank indicators to verify the economic and political conditions within the country. This analysis is aiming at addressing the question: Can we affirm that the peacekeeping operations are responsible for the periods of socioeconomic development in the States during democratic ruptures? Finally, the analysis of the Haitian case enables us to infer that similar peacekeeping operations have contributed in the same direction with other countries. This assertion can be corroborated through an analysis of the indicators from another operation, conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Democracy and development in Political Science

The studies investigating the correlation between democracy and development have taken on a relevant position in the field of Political Science in the second half of the last century, when part of the literature began to investigate the connections between the government regime and the overcome of the socioeconomic problems of States. The main issue involved the empirical-theoretical articulation about the functioning of contemporary democratic governments and the factors that directly or indirectly influence a country's development process - as well as the democratic ruptures' effects for investigating the apparent interruptions of economic and social growth.

Initially, the studies that started this tradition lacked quantitative instruments of analysis and empirical evidence, and, therefore, were restricted to theoretical or comparative investigations, but which presented gaps. However, these initial analyses were fundamental to guide the debate in Political Science.

These studies had as a starting point the generic premise that the higher the degree of development, the greater the probability of maintaining democratic stability, because the democratic system would be perceived as a kind of consequence of development (Lipset, 1967 49): that is, this hypothesis, which would be tested by later authors, argued that the maintenance of democratic governments was conditional to a previous situation of democratic stability.

One of the earliest significant studies on the relationship between democracy and development was published by Seymour Martin Lipset, in the United States in 1960. This work that sought to comprehend various elements, including the political behavior of American society and the link between legitimacy, democracy and economic development (Matos 1969: 240). In the study, the author initially conceptualizes democracy as a political system equipped with constitutional mechanisms of peaceful government change, while preventing the perpetuation of a single ruler in power (Lipset, 1967, p. 45-46).

The author presents one of the most interesting arguments to underscore the importance of this field of study within Political Science by stating that.

Perhaps the most common generalization, associating the political systems to other aspects of society, is that democracy is related to the economic development situation. The more prosperous a nation, the greater the chance that it will sustain democracy.

From Aristotle to the present, men have argued that only in a wealthy society, in which relatively few citizens live at the level of real poverty, there may be a situation in which the mass of the population intelligently participates in politics and develops the necessary self-discipline to avoid succumbing to the appeals of irresponsible demagogues (Lipset, 1967, p. 49).

In this context, Lipset opted for a comparative approach, studying states with similar political cultures. Regarding this article, which focuses on Haiti, it is important to highlight that the author sought to analyze Latin American countries based on the criterion of whether these states had a history of elections in the post-World War I period or not. Additionally, he considered other elements that characterize democracies. Consequently, Lip-set classifies Haiti as one of the nations that lived under the condition of stable dictatorship during the period under study, alongside Cuba, Bolivia, Honduras and nine other nations in the region (Lipset, 1967, p. 48-49).

By comparing the levels of industrial development, wealth, urbanization and education among the states, the author concluded that all these variables have an impact the level of democracy of a country. For instance, concerning education, the finding at the time was that more dictatorial nations exhibited higher rates of illiteracy (Lipset, 1967, p. 54-56).

However, Lipset's findings stirred controversial, since there were States that did not fit in the theoretical model, he proposed. For instance, China, which presented a high degree of economic development, maintained an authoritarian government. The expectations that the Chinese people would naturally progress toward democratization did not materialize. One of the criticisms levied against Lipset's work is that it did not consider the numerous regional inequalities. States experiencing acute phenomenon in an acute way tend to have problems for in establishment of democratic regimes.

Nonetheless, Lipset's studies that comparative investigations between development and democracy were consolidated in the field of Political Science. Various authors sought to find analysis' methodological tools to empirically demonstrate the relationship between democracy and development. In his work, Adam Przeworski begins by corroborating the earlier criticism previously made by Lipset regarding common perceptions: the notion that poor countries tend toward authoritarianism while affluent nations tend toward democracy (Przeworski, 2000, p. 78). According to the author, two commonly attributed motives for associating the incidence of democracy to the level of economic development: the first is that democracies are more likely insofar as countries would economically develop; the second indicates that democracies are more likely to survive in developed nations (Przeworski, 2000, p. 88). The first explanation is associated with endogenous theories that operate within the framework of the modernization thesis introduced by Lipset. The alternative perspective is exogenous and posits that democracy can thrive to survive whether the country is modern, but it is not, actually, a product of modernization.

One of the author's central conclusions is that analyzing whether the regime is democratic or dictatorial alone is insufficient to understanding the development process. It is equally essential to examine the conditions under which the regime emerged and evolved (Przeworski, 2000, p. 137-138), thereby enabling a qualitative expansion of the investigation.

Fernando Limongi, n the ther hand, underscores the importance of Robert Dahl's studies, especially in relation to the concept of polyarchy. These studies aimed to challenge the prevaling pessimistic viewpoint in earlier literature, which suggested that democracies were only possible in countries that developed during the 19th century (Limongi, 1997, n.p).

This perspective relegated poorer states to an inevitable condition of authoritarianism, even if they later found ways to achieve development. The idea of verifying the level of polyarchy allowed for an evaluation of regime transitions, contrasting the classical theory of modernization, which implied a single path.

According to Dahl, democracy would only be a hypothetical model of government, since its existence hinges on the satisfaction of the interests of nearly all citizens (Dahl, 1971, p. 13). It is, therefore, a theoretically plausible proposal but improbable proposition. Dahl's pluralistic proposal suggests that we should analyze governments based on the interplay between participation and contestation, which could create polyarchic governments, i.e., which he defines as "relatively, but not completely democratic" (Dahl, 1971, p. 18). In this sense, the Dahlsian theory would allow verifying the processes that lead States to transit from closed and authoritarian systems to models more open to participation, which opposes the pessimism in the theories of modernization and discusses that the chances of democracy depend on pluralism (Limongi, 1997). This methodological endeavor is made possible by Dahl's theory, addition which posits not only the concept of polyarchy but also introduces three other types of governments:

1) closed hegemony, a situation in which there is no dispute (without competitive elections) or inclusion (without rights to political participation); 2) inclusive hegemony, a political system in which there is no dispute (without competitive elections), but there is inclusion (with rights of political participation); and 3) competitive oligarchy, a political framework in which there is contestation (competitive elections), but without inclusion (without universal rights to political participation) (ABU-EL-HAJ, 2014, p. 14).

Each one of these regimes has the potential to undergo democratization, going through different paths and reaching some degrees of contestation and inclusion that would bring them closer to the idea of polyarchy.

In more contemporary times, other authors have also contributed to this debate. For instance, Boix and Stokes start from the premise that the debate proposed by Przeworski (2000) indicates the correct direction: the notion that endogenous theories alone are insufficient to explain the phenomenon, while exogenous theories tend to be more appropriate (Boix and Stokes, 2003, p. 517). This premise guides their study. In this respect, the research concludes that a developed states undergoing the democratization process is less likely to experience a democratic rupture and become a dictatorship.

Conversely, underdeveloped states that adopt democracy as their form of government are more susceptible to political setbacks leading to ruptures.

This brief discussion of the literature provides a basis for analyzing the case study proposed for this article, Haiti, as well as designing the conclusions about the Haitian situation for other peacekeeping operations.

The relationship between democracy and democratic ruptures in Haiti

The United Nations sanctions peacekeeping operations based on chapters vi and vu of the United Nations Charter. Chapter vi seeks to resolve conflicts through peaceful negotiation, while Chapter VII allows for the imposition of solutions (Bracey, 2011, p. 317). These operations were first employed by the un system at the end of the 1940s, when over 20 states provided troops to join in ceasefire agreements between Arabs and Palestinians. During the Cold War, only a few similar initiatives were approved, due to the adversarial stance between the United States and the Soviet Union, which limited the possibilities for consensus. However, the end of bipolarity in the early 1990s allowed more conflicts to be solved with the support of the UN troops, particularly in the Asian, African and Latin American countries.

It is important to note that peacekeeping operations are complex instruments aimed at establishing order, and they do not adhere themselves in a single template. Due to the specificities of each conflict, local and global demands, the unfolding of actions in the field, and the configuration of the Security Council in each period, the mandates of missions can encompass relatively distinct elements. This article does not aim to delve into the various types of peacekeeping operations or the internal debates within the United Nations and academia regarding these endeavors. Nevertheless, it is worth highlighting that some literature categorizes missions can be divided into three distinct phases, with the third phase linked to the period after 1999 when the un began to prioritize incorporating elements of peacebuilding to reconstruct the countries affected by wars (Gowan, 2018, p. 422-423)1.

Additionally, it is pertinent to argue that numerous studies have analyzed the performance of MINUSTAH and other missions during the 21st Century. Carhahan, Durch and Gilmore (2006) explain that United Nations peacekeeping missions currently spend billions each year and frequently face criticism for a wide array of damage they are thought to the economies of the war-torn regions where they deploy. These critiques include allegations of inducing inflation, dominating the real estate market, co-opting local talent, and drawing highly capable individuals away from government and the local private sector. Despite the broad range of criticisms, however, data on these economic impacts had not been systematically collected or analyzed.

In total, as the first semester of 2018, the un had authorized the completion of 71 peacekeeping operations, some of which concluded without effectively resolving the issues for which they were established. Out of this total, 15 were initiated in the 2000s and 2010s, periods during which the United Nations began to employ peacekeepers not only to address military matters but also to promote socioeconomic development in the target states through international transfer of public policies. Table 1 illustrates the operations initiated from the 2000s onwards.

Table 1 Peacekeeping Operations from 2000 onwards

| Acronym | Operation | Beginning | End | Country | SC Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNMEE | United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea | 2000 | 2008 | Ethiopia/Eritrea | 1312 |

| UNMISET | United Nations Mission to Support East Timor | 2002 | 2005 | East Timor | 1410 |

| UNMIL | United Nations Mission in Liberia | 2003 | - | Liberia | 1497 |

| UNOCI | United Nations Operation in Côte D'Ivoire | 2004 | - | Côte D'Ivoire | 1528 |

| MINUSTAH | United Nations Stabilization Mission for Haiti | 2004 | 2017 | Haiti | 1542 |

| ONUB | Operation of the United Nations in Burundi | 2004 | 2007 | Burundi | 1545 |

| UNMIS | United Nations Mission in Sudan | 2005 | - | Sudan | 1590 |

| UNMIT | United Nations Integrated Mission in East Timor | 2006 | 2012 | East Timor | 1704 |

| UNAMID | United Nations and African Union Mission in Darfur | 2007 | - | Darfur | 1769 |

| MTMI IDT AT | United Nations Mission in the Central African | 2007 | 2010 | Central African Republic and | 1913 |

| MINUKCAI | Republic and Chad | Chad | |||

| MONUSCO | United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo | 2010 | - | Democratic Republic of Congo | 1291 |

| UNISFA | United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei | 2011 | - | Abyei | 1990 |

| UNMISS | United Nations Mission in South Sudan | 2011 | - | South Sudan | 1996 |

| UNSMIS | United Nations Supervision Mission in Syria | 2012 | 2012 | Syria | 2043 |

| MINUJUSTH | United Nations Mission For Justice Support in Haiti | 2017 | 2019 | Haiti | 2350 |

Source: Developed by the authors based on data from UNO (2018).

According to the author, the Brazilian government chose to participate in missions based on chapter VI, as they require the consent of the parties involved (Bracey, 2011, p. 317). They prefer to operate in strategically important countries for national expansion plans, such as the Latin America ones and Africa ones (Diniz, 2007, p. 316). For the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, engagement in peacekeeping operations can extend the state's power and prestige projection, which is useful for recognizing Brazil as a regional power or, at the very least, expanding its capacity to negotiate for a possible permanent seat on the Security Council.

Having briefly explored the bibliography that correlates democracy and development, outlined the role of peacekeeping operations within the un system, we should investigate the case study proposed for this article. An analysis of Haiti's historical process demonstrates that the country has experienced numerous phases of democratic consolidation efforts, alternated with severe ruptures caused by coups throughout the entire last century and even at the beginning of the 2000s - the last of them in 2004, when Jean-Bertrand Aristide was deposed. In the 1990s, the repetition of this pattern associated with changes in the international system logic, led to the approval of several peacekeeping operations conducted by the United Nations, always with the aim of establishing political stability to the state to subsequently contribute to the development process.

Before delving into the specifical context of the 1990s and the 2000s, however, it is worth noting that the occupation of the Haitian territory dates back to 1492 with Christopher Columbus arrival in the region. Later, at the end of the 18th century and under the ideological influence of the French Revolution, a great rebellion marked the country's independence process (Montenegro, 2013, p. 23-24), making Haiti the first country in the Americas to abolish slavery. However, this seemingly progressive change left limited lasting impact, as the local reality would become turbulent in subsequent years. In the pre-World War scenario, driven by discourses tied to the Monroe Doctrine, the United States invaded the country as a way to avoid the German influence in Central America. Later, during the Cold War, the Duvalier Era began in Haiti: Dr. François Duvalier, with the support of the U.S. government, would establish himself as a dictator until 1971, when he was succeeded by his son, Jean-Claude. It was decades of violence and repression, culminating in increased instability in the second half of the 1980s.

Several political agitations made the Haitian situation troubled, until 1990 when, under the observation of the United Nations and the Organization of American States (OAS), free elections were held. These elections were won by the former Catholic priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who would be ousted the following year by a military coup and would only return to power with support of the UN in 1994. Aristide was re-elected in 2000, however in a plea marked by allegations of fraud. In 2004, former military personnel initiated an uprising, which resulted in the withdrawal of Aristide from the country on February 29th (Montenegro, 2013, p. 48) This event prompted the Security Council of the United Nations to approve the creation of another peacekeeping operation aimed at stabilizing the situation in Haiti, this time under Brazil's command, and it lasted until 2017.

According to Simões, the approval of MINUTAH is closely related to the deteriorating political and social situation in Haiti, which worsened public security, spread violence during a civil war, and resulted in the collapse of local institutions, along with an increasing in human rights violations (Simões, 2011, p. 23). It is important to emphasize that safeguarding human rights is one of the fundamental principles of a democratic rule of law, and therefore, peacekeeping operations aimed to restore democracy must address these types of concerns.

The new peacekeeping operation had several objectives, including the protection of civilians, pacifying the country, disarming various political groups, and contributing to the process of democratic transition (Rodrigues, 2015, p.149). Leading the peacekeeping mission was part of the Brazilian strategic plan to engage in Latin American territory, within a broader context of international regional cooperation in Latin America (Rodrigues, 2015, p.146). The operation's mandate included the implementation of a Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program to curb escalating violence, promote human rights, and organize a UN-monitored election process to ensure transparency electoral process and subsequently legitimacy for the elected leader (Lemay-Hébert, 2015, p. 721). From an operational perspective, the new mission would consist of a contingent of 1,622 police officers and 6,700 military personnel.

Some scholars view MINUSTAH as distinct from other authorized operations in Haiti, primarily because the emphasis on security was rooted in the commitments made by contributing states, which would provide the police and troop contingents to fulfill the mandate. Secondly, there was a stronger emphasis on human rights in the Security Council's resolutions placed these issues at the forefront of the UN'S presence in Haiti (Lemay-Hébert, 2015, p. 722). This justified all the international policy transfer efforts undertaken by Brazil between 2004 and 2017 as a means to implement actions that, from the Brazilian perspective, were essential for promoting social and economic development. This, in turn, could represent an effort to address some of the institutional weaknesses experienced by the Caribbean state.

The MINUSTAH can be considered the primary operation with Brazilian troops in the country, and it also included another significant aspect: Brazil assumed leadership in the field. In addition to two pro tempore appointed commanders, the operation had a total of 11 Brazilian force commanders, without rotation from representatives of other nations. These commanders were: Augusto Heleno Ribeiro Pereira (September 2004 to August 2005), Urano Teixeira da Matta Bacellar (September 2005 to January 2006), José Elito Carvalho Siqueira (January 2006 to January 2007), Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz (January 2007 to April 2009), Floriano Peixoto Vieira Neto (April 2009 to April 2010), Luiz Guilherme Paul Cruz (April 2010 to March 2011), Luiz Eduardo Ramos Baptista Pereira (March 2011 to March 2012), Fernando Rodrigues Goulart (March 2012 to March 2013), Edson Leal Pujol (March 2013 to March 2014), José Luiz Jaborandy Junior (March 2014 to August 2015), and Ajax Porto Pinheiro (October 2015 to October 2017). The mission chief commanded a total of 6,700 military personnel, and the initial composition of MINUSTAH included contingents from Argentina, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chad, Chile, Croatia, France, Jordan, Nepal, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Turkey, and Uruguay.

Resolution 1542 indicates that the operation was structured around three main pillars, with the following objectives: a) ensuring a safe and stable social environment, which included the need to disarm and demobilize rebel groups; b) creating conditions for the conduct of free and secure democratic elections at the municipal, parliamentary, and presidential levels; c) guaranteeing human rights for the Haitian population at multiple levels (Aguilar & Moratori, 2011, s/p). This leads us to reflect on the comprehensive scope of the operation (Le Chevallier, 2011, p. 120). Therefore, MINUSTAH can be considered an ambitious mission, mainly because some of the objectives could not be achieved solely by the mission itself, as the promotion of democratic governance would depend on other actors (Le Chevallier, 2011, p. 118). This effort included the security of children and women and concern for refugees, complemented by bilateral policies between Brazil and Haiti. These policies aimed to provide essential services that would ensure the country's socioeconomic development, which could be achieved through bilateral and triangular actions of international policy transfer, including family farming and child nutrition programs based on the Zero Hunger Program, and the drilling of artesian wells, for example, was implemented.

According to Aguilar and Moratori, the operation was not proposed solely to restore order in Haitian territory but also to create long-term structural conditions that could lead the nation towards development. This would be achieved through the articulation of public policies addressing the root causes of the conflict (2011, s/p). In this context,

The operation in Haiti relates to the concept of human security, which shifted the exclusive emphasis on territorial issues to a broader focus centered on the security of individuals, human beings. This shift moved the focus from security based on weapons to security obtained through sustainable development (Aguilar & Moratori, 2011, s/p).

This argument helps us understand that indeed, integrating peacekeeping operations is part of the Brazilian state's actions in the project of international integration. The conflict triggered in Haiti, as well as the alleged French invitation to participate in the endeavor, opened a window of opportunities for the country. This allowed Brazil not only to participate in a major operation but also to lead operations on the ground. In the post-Cold War scenario, it was undoubtedly the greatest opportunity to demonstrate international action capability in collective security, contributing to sustaining the narrative of Brazil's inclusion as a permanent member of the Security Council in a potential reform scenario. This narrative was widely disseminated by the press but not officially integrated into the state's narrative, as we will see below.

Therefore, it is essential to analyze the empirical data at our disposal in order to verify the history of Haiti's political behavior. The basic data obtained from the Polity IV database demonstrate how unstable the Haitian reality was in the 1990s. Polity IV is an indicator of democracy that measures political regimes on a score ranging from -10 (highly autocratic States) to +10 (highly democratic countries). This score is obtained from the analysis of four distinct variables: rules for the recruitment of the Executive, competitiveness of this recruitment, openness, and limits to the head of the central Executive power (Kellstedt and Whitten, 2015, p. 126). In the figure, the colors of the lines represent the condition of the regime: the green lines represent periods of transition; the blue color corresponds to the stability of the regime; red represents a period of factionalism; finally, the black color symbolizes an interregnum, that is, the time when the State is considered occupied by foreign forces.

Polity IV displays significant variation in Haitian democratic experiences. The red color indicates periods of internal conflicts that resulted in political ruptures, while green refers to the transition stages. Thus, it is evident that the 1990s represent a long period of non-democratic governments, a reality that later shifted in two brief transition periods ultimately lading to a black dashed line. This line signifies that, according to the methodology of Polity IV, the country became bankrupt or occupied starting from 2010, the year of the earthquake occurred.

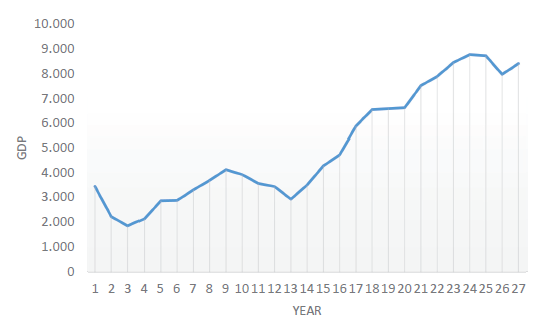

When examining another indicator, the Freedom House, Haiti is categorized as a partially free state, as shown in Figure 1. This classification is as a consequence of issues such as corruption, institutional instability and foreign influences. The Freedom House employs a scoring system oscillating from 1 (indicating more freedom) to 7 (indicating less freedom).

Source: Developed by the authors based on the data of Freedom House (2018b).

Figure 1 Haiti's freedom status (Freedom House)

After analyzing this data, we can observe that the Haitian reality is characterized by prolonged periods without democracy, although Przeworski acknowledges that dictatorial regimes in Latin America are more unstable than democratic ones (Przeworski, 2000, p. 86).

It was during the extended period marked by the red line in Polity iv, just over ten years ago, that the United Nations established peacekeeping operations to assist the country. In total, there were six operations, including MINUSTAH, which was approved after Aristide's deposition in 2004. Before the operation commanded by Brazil, there were others, such as the United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH), in 1993, the United Nations Support Mission in Haiti (UNSMIH), in 1996, the United Nations Transitional Mission in Haiti (UNTMIH) and the United Nations Civil Police Mission in Haiti (MIPONUH), both in 1997, and the International Civil Support Mission in Haiti, in 2000. This number of interventions by foreign forces suggests that, democratically, that is a State with unstable institutions, which has difficulties to establish a sustainable political regime - and which has also led to the reality of bankruptcy, noticed in Polity IV. Later we will relate these periods with the socioeconomic development indicators.

It is important to emphasize that the peacekeeping operations are emergency devices triggered by the UN in cases of civil conflict, and legitimated by chapters VI and VII of the Charter of the United Nations, which assure the arbitrated solution for conflict and the granting of peace by strength, respectively (Bracey, 2011, p. 317). During the Cold War, the architecture of the international system practically did not offer many possibilities for missions to be approved, since the United States and the Soviet Union composed the Security Council on the condition of permanent members, which could end in veto. However, the end of the bipolarity caused the peace missions to return to the United Nations agenda. In addition, in the 1990s the un began to promote several international conferences in order to give particular attention to the social problems involving the States (Alves, 2001, p. 43) - which contributes to thinking about the need for approval of peacekeeping operations to stabilize the political scenario and provide development.

MINUSTAH2, approved through the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1542, was organized around three central pillars, each with specific objectives : a) ensuring a safe and stable social environment, including the disarmament and demobilization of rebel groups; b) creating conditions for conducting free and secure democratic elections at the municipal, parliamentary and presidential level; c) guaranteeing human rights for the Haitian population across multiple dimensions (Aguilar and Moratori 2011). These dimensions encompassed the safety of women and children, concern for refugees and displaced people, and the institutional promotion of essential services that could facilitate the socioeconomic development of the country through the international transfer of public policies.

Aguilar and Moratori (2011) underscore that the operation was not solely aimed pacifying the country but primarily intended to establish the structural conditions for Haiti's development through the implementation of public policies aimed at reducing the likelihood of future conflicts. In this regard, Brazil was tasked with providing support to the Haitian government in identifying, formulating and implementing solutions to the fundamental problems contributing to conflicts, such as social inequality. The authors point out that during this process, it was crucial to consider Haiti's dire socio-economic conditions. Haiti ranked as one of the poorest countries in the world, occupying the 146th position out of 147 in the Human Development Index. Approximately 54% of its population survive on less than one dollar per day, with an inflation rate that reached 40% in 2004. Consequently, these indicators indicated that Haiti not only had a tumultuous democratic history but also suffered from poor living conditions for its population.

Furthermore, another significant indicator reflecting the country's conditions is the ranking of corruption measured annually by the NGO International Transparency. Haiti ranks 157th out of 180 States, making it one of the most corrupt nations worldwide.

It becomes evident that the peacekeeping operation of the objective was not only to restore democracy , for subsequently ensuring the resumption of the country's socioeconomic development. This aligns with the theorical discourse proposed in the literature and briefly reviewed in the previous section of this article.

Haiti and World Bank indicators

The theoretical analysis discussed here leads us to consider Haiti as an intriguing case study to empirically investigate the debate surrounding the relationship between democracy and development, as proposed in the literature. According to the proposal of this article, we now use the World Bank indicators to verify the Haitian case. Methodologically, we will employ some of the variables articulated by Lipset (1967, p. 50): specifically, GDP and per capita income.

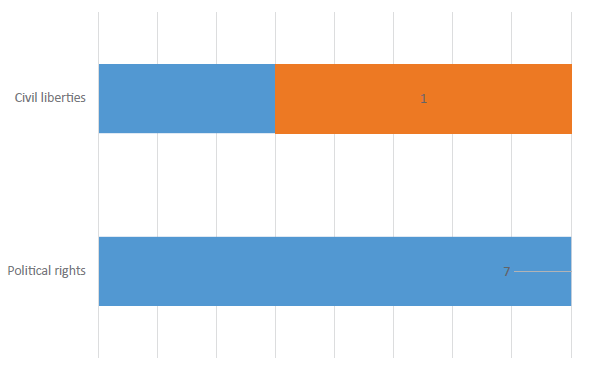

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data reveals that the sum of the country's wealth fell from US$3.474 billion in 1991 to US$1.878 billion in 1993. The period corresponds with the troubled Aristide deposition period from power. In 1994, when the president was reinstated, Haiti's GDP experienced growth, reaching its peak of us$4.154 billion in 1999. It is important to emphasize that throughout this period, the incessant presence of un peacekeeping operations persisted in Haitian territory rather than a period marked by the existence of autonomous democracy.

In 2000, the year of Aristide's new election, which was marred by allegations of fraud and incessant opposition movements, the indicator experienced another decline. It would only begin to recover in 2004 when the president was deposed once more, and MINUSTAH was established by the United Nations. This period was marked by the acceleration growth in the indicators, with a brief brake at the rise between 2008 and 2010, possibly due to the impact of the global economic crisis. The peak of economic growth, as depicted in Figure 2, corresponds to the year 2014, with a GDP of US$8.776 billion - showing not facing any development inflection, therefore, neither during the 2008 crisis of nor immediately after the earthquake that struck the country in 20103

This suggests that the international interventions promoted by the UN system align with periods of domestic wealth growth, whereas the brief republican periods, under Aristide's rule, represented moments of decline in GDP. It is worth emphasizing that, according to Correa, the Brazilian argument at the time showed that the previous attempts at reconstruction the country had failed because they were largely backed by a safety concerns, neglecting other variables of the problem, such as socioeconomic issues (Correa, 2014, p. 129-130). This brief analysis, while not delving deeply into the contextual debate of the periods in question, challenges the theory that democratic governments inherently generate economic growth. One of the potential issues could be the low quality, weakness or even instability of democracy and institutions.

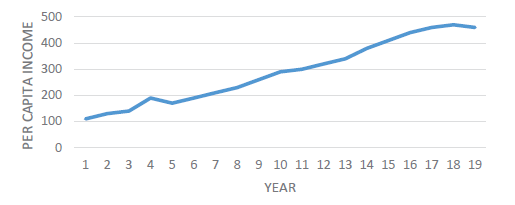

The World Bank database also enables us to explore the relationship between democracy and the Haiti's per capita income. This variable exhibits a chart with a format very similar to that of the Gross Domestic Product, allowing for a brief observation regarding concerning to the decrease in the percentage during the management of Aristide, in the beginning of the 2000 years, succeeded by a phase of uninterrupted growth until 2010. The economic crisis and the earthquake in 2010 likely contributed to the income reduction in the country.

Subsequently, per capita income growth resumed until 2014, followed by a new decline until 2016, the last year available for analysis, consistent with the GDP indicator, as previously shown. Consequently, the two wealth indicators - per capita income and the Gross Domestic Product - exhibit a remarkable similar behavior in the historical series comparison within the World Bank's data.

The observation of Figure 3 also suggests that establishing a direct relationship between the periods of democratic governance and the improvement of development indicators. This is because the interval of higher per capita income growth coincides with the period of democratic rupture and the attempt to restore the country's sociopolitical conditions of the country through the peacekeeping operation commanded by Brazil.

Source: Developed by the authors based on data of World Bank (2023d).

Figure 3 Haiti's per capita income

The descriptive analysis of the wealth variables (GDP and per capita income) leads us to a reflection: drawing inferences from the data within the investigated period, on these two specific variables does not allow us to conclusively assert that democracy corresponds to a higher degree of economic development in Haiti. This is because the moments of wealth indicators improvement precisely align with the phases of democratic rupture.

It is important to note that Brazilian foreign policy coordinated several elements of international policy transfer during the MINUSTAH mission. Although the objective of this article is not to delve into discussions about bilateral international cooperation between the two countries or triangular cooperation initiatives, it worth mentioning that such actions were primarily coordinated to promote social and economic development in Haiti. However, certain initiatives can also be understood from the perspective of strengthening the political system to rebuild the democratic regime. For instance, there were initiatives involving the dispatch of electoral technicians to the Caribbean to address issues related to Electoral Justice. In total, the Brazilian government, through the Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC), initiated a total of 114 cooperation projects in Haiti, mainly in the fields of Agriculture (essential for combating hunger) and Development.

This discussion leads us to consider that Haiti's pacification depends on the improving socioeconomic indicators, as mandated by some missions, as well as the reestablishment and strengthening of the democratic regime. The perspective of development as a security paradigm is not new for Latin America, especially concerning external pressures on the region. These two factors, security and development, began to be considered interrelated, primarly within the context of Cold War international politics, where the U.S. government saw the possibility that the two terms had a connection. In this scenario, without development, there would be no security, as economic problems could create opportunities for the insertion of supposed communist models in Latin America. This realization has been incorporated into Brazilian foreign policy at various points in our contemporary history. For example, we can highlight the elaboration of the Pan-American Operation during Juscelino Kubitscheck's administration (Altemani de Oliveira, 2013, p. 84), and certain aspects of the Diplomacy of Prosperity, adopted as a paradigm by the military president Costa e Silva (Altemani de Oliveira, 2013, p. 119).

The causal link between development and security is a central piece in understanding how international cooperation, built around a peacekeeping mission, can contribute not only to pacifying a conflict-ridden territory but also to promoting sustainable peace - a crucial point for United Nations-led operations. Furthermore, development cooperation typically includes the promotion of democracy , a factor present in the mandates of peace missions in Haiti. In this context, international policy transfer plays a fundamental role in the actions of the cooperating country, which incorporates such initiatives into its foreign policy agenda.

In general, research considers that processes of international policy transfer occur when a specific policy from one country can be employed in another political system, with or without mediation (Porto de Oliveira, 2016, p. 224). Additionally, the literature distinguishes that,

In terms of scale, diffusion can be understood as the adoption of policies by a group of countries or governments, while transfer studies are mainly concerned with assumptions of supposedly unidirectional movement involving the displacement of policies to one [government] or a small set of governments (Porto de Oliveira & Farias, 2017, p. 19).

Some of these studies, according to Dolowitz, focus on analyzing the voluntary transfer process, while they may partially overlook less voluntary cooperation and the roles of international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, NGOs. They may also inadequately consider the human aspects and ideologies related to these mechanisms (Dolowitz, 2017, p. 40).

In this context, we can understand that the 114 projects established between Brazil and Haiti (or through triangular cooperation) may have had an impact on promoting improvements in social and economic indicators, some of which are directly related to the human rights agenda. For instance, certain agreements in the field of Agriculture were executed by the Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (Embrapa), such as two initiatives for the transfer of technologies for sustainable cashew and cassava production, signed in 2005, a trilateral cooperation between Brazil, Haiti, and Nicaragua to train local producers interested in growing vegetables, and it was developed by the General Coordination for Combating Hunger in 2008. Additionally, there were several projects in the fields of family farming and food security.

Although the Caribbean state had potentially cultivable areas, there were numerous technical deficiencies in food production. Therefore, Brazilian cooperation precisely addressed this demand and contributed to the development of the agriculture sector, which was considered a priority by internal actors. The argument of certain participants in the process indicates that the Brazilian government could help meet specific local demands by transferring public policies to Haiti, which could alleviate the serious food problems faced by the local population. Based on this, the state sought to establish partnerships including with the UN's World Food Programme (WFP), to find ways to structure a family farming system, strengthen local production and, consequently reinforce school feeding programs. This effort aimed not only to improve the nutritional conditions of children but also to encourage parents to keep their children enrolled in school as a means of promoting long-term development. Therefore, nutrition and education are closely related areas in this type of context.

This context led Brazil to pursue various assistance strategies to address local problems, creating, according to some literature, a series of long-term commitments to development, even though Brazil's national conditions were quite limited (Simões, 2011). From the Haitian perspective, we can say that cooperation work is linked to the absence of local conditions for the provision of internal security, economic development, and human rights autonomously (Feldmann & Montes, 2008, p. 246), as the State was in turmoil due to the numerous political, civil, and military problems. This situation would worsen with the 2010 earthquake, which is why there was an appeal for external assistance. In this regard,

After the earthquake, the Brazilian government increased its military and economic responsibilities in Haiti. At the same time, its actions became more aligned with local demands and international expectations rather than to South American alliances. For Brazil, the assistance offered marked a continuation of its presence in Haiti since 2004, but it also revealed the expansion of the scope of its commitments as part of the active donor community in this country. In addition to the immediate dispatch of medicines, food, water, and essential products, the Lula government committed to a donation of $350 million and a 100% increase in Brazilian military contingents for MINUSTAH. The country also clearly intended to play a prominent role among bilateral donors and multilateral organizations in successive meetings dedicated to outlining the lines of action for international cooperation to rebuild the Haitian nation. (Hirst, 2012, p. 21)

As we have argued previously, the United Nations peace mission in Haiti reshaped a reality in which Brazil made the Caribbean country the primary destination for international cooperation. This led to the execution of various international projects by Brazilian domestic actors such as Embrapa and the Ministry of Health. It is interesting to note that in the context of the UN operation, both the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the GDP per capita in Haiti increased. This may have been a reflection of these actions aimed at promoting economic and social development. However, the curve of the graph suggests that the Haitian GDP per capita did not grow in proportion to the State's Gross Domestic Product. This indicates that the country's increased wealth did not translate proportionally into higher income for the population. This may suggest that if the peace mission, directly or indirectly, had positive effects on the country's development and subsequent improvement in Haiti's economic conditions, there was no proportional income distribution.

However, when we compare the growth of the country's per capita income with the number of cooperation projects signed by the Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC), we do not see a correlation between the two factors. In other words, the GDP per capita did not grow in proportion to the number of agreements concluded. Stated differently, even though there was a significant increase in the number of cooperation projects between Brazil and Haiti, this movement did not directly impact Haiti's Gross Domestic Product. Therefore, the increase or decrease in the number of cooperation agreements between Brazil and Haiti did not directly affect the income of the Haitian population. This demonstrates an absence of a relationship between the two variables studied and reinforces the criticisms that the international transfer of Brazilian public policies had limited concrete impacts on Haitians, considering only the "per capita income" variable.

As the aim of the case study methodology is to obtain insights from a particular phenomenon and generalize them to similar scenarios (Yin, 2008), it is essential that we seek to investigate other peacekeeping operations and verify whether the conclusions obtained from the Haitian reality correspond to those experienced by states that have also faced democratic crises. For this purpose, we have selected from Table 1 the peacekeeping operation of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which began in 2010 and was led by Brazilians on two (between April 2013 and December 2015 and later, from May 2018 onward). The choice of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for comparison was made because it is another peacekeeping mission that involved Brazilian participation and had Brazilian force commanders during certain periods, similar to Haiti but to a lesser extent T Therefore, the operation was also treated in a highly strategic by the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Armed Forces.

Polity IV data from 2014 indicate that the African country does not have a long history of democratic regularity. The indicator shows that, in contrast to the Haitian reality, with oscillations, the Congolese state had a score close to -10 between the 1960s and 2000s, indicating a strong association with an autocratic regime.

On two opportunities, in the early 1960s and later, between the mid-1990s and 2005, the Democratic Republic of Congo is indicated by Polity IV as a bankrupt or occupied State, marked by the black line. The peacekeeping operation was established shortly after that second period, through Security Council Resolution 1291, when the green line indicates a transition to stability corresponding to the blue color, coinciding with the end of the second civil war faced by the country, which lasted from 1998 to 2003.

Although the end of the conflict did not resolve all political and social problems, the Polity IV score indicates that from that moment onwards, a transitional period began, lasting until mid-2007, when the situation in the country stabilized to a degree close to level 6. Therefore, when the peace operation was approved by the UN in 2010, the Democratic Republic of Congo was already experiencing a stable regime.

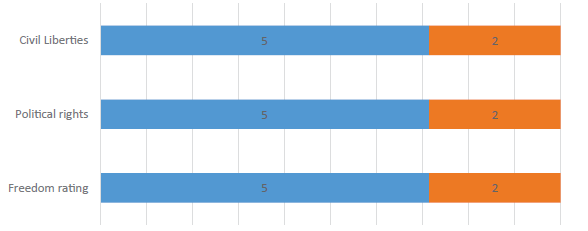

However, Freedom House (2018) indicators from 2018 classify the country as non-free, with political rights score of 7 and a civil liberties score of 6.

Source: Developed by the authors based on data of Freedom House (2018a).

Figure 4 Democratic Republic of Congo's freedom status (Freedom House, 2018a)

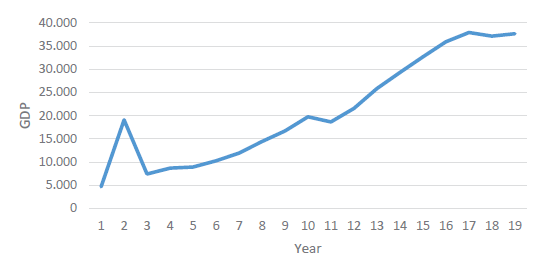

The analysis of World Bank data also suggests that the Congo's case presents singularities that do not allow us to explain the results of the peace in the same way as the investigation in Haiti. For example, the State's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) experienced a growth peak between 1999 and 2000, during the civil war, followed by a gradual increase from 2001 - almost nine years before the establishment of the United Nations operation, as shown in Figure 5.

Source: Developed by the authors based on data of World Bank (2023a).

Figure 5 Democratic Republic of Congo's GDP

In any case, it is possible to infer that the mission contributed, in some way, to the country's GDP to continuing to grow and reaching its highest level in 2015, when the Gross Domestic Product recorded the value of us$37.9 billion during the management of the Brazilian command. However, un operation was not solely responsible for this growth but contributed to maintaining stability in the indicator.

Regarding per capita income, the indicator showed an increasing starting in 2003, from us$100 to a peak of the us$460 between 2015 and 2016. Therefore, the peace operation did not initiate the reversal of the population income, but it may have contributed to the maintain these indices. Nevertheless, there was a decline in per capita income from 2017 onwards, and, according to Figure 8, the per capita income of the Congolese people is far from reaching the same level of 1984, which was the highest value achieved, at US$950.

Source: Developed by the authors based on data of World Bank (2023b).

Figure 6 Democratic Republic of Congo's per capita income

However, when comparing the World Bank variables with the Polity iv indicator, we conclude that the growth of the analyzed indices occurred at the end of the state bankruptcy stage and during the transition period following the war, continuity during the stabilization of the regime. Thus, the Congolese case is particular compared to the Haitian case. The country experienced GDP and per capita income development during both democratic periods and stages of institutional rupture.

In conclusion, Yin's guidance is that the generalization of a case study should consider the theoretical conclusions achieved through the method (Yin, 2008, p. 59). Returning to the hypothesis that guided this research, which stated that peacekeeping operations, usually established during democratic rupture, contribute to improving income and wealth indicators, we find that the comparison with the African country corroborates this idea. Both Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo showed improvements in the specific variables analyzed in this study while there was an ongoing UN operation. Even though the Congolese case the improvement of living conditions had passed the period of transition exposed by Polity IV and had reached the apex in the stability of the regime. Therefore, it is not two identical events, but currently events that have similar characteristics that can be analyzed with the hypothesis.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that peacekeeping operations are linked to the development concerns and are not purely military actions. These missions whose proposal would be to hypothetically guarantee the order to the receiving States. The missions are, at the end, multidimensional strategies, mainly in the post-Cold War context (Gilmore 2015, p. 7), whose proposals include concerns with human security and socioeconomic development.

Final considerations

From this brief analysis of Haiti, generalized with the further insights into the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, we can affirm that World Bank data prove that the peacekeeping operations established by the un Security Council contribute to improving income and wealth indicators in recipient countries. The Haitian case presented as singularity, the fact that, despite the problems faced by the nation, in which period of growth coincided with a moment of democratic rupture. because the previous governments periods based on democracy did not result in development.

This suggests that even during times of political instability may produce some form of development may occur, mainly due to external actions. Moreover, democratic governments may, in turn, result in a drop in the indicators. Therefore, there is no directly proportional relation between the democratization of the State and the increase in the indicators' performance and, in addition, it is possible to empirically verify that. Moreover, democratic governments with legitimacy problems, including allegations of corruption and electoral fraud, may face greater difficulties in promoting development than stable authoritarian governments or countries under external intervention.

For that matter, it is worth another reflection, which binds to the discussion proposed by Robert Dahl's concept of Polyarchy: to analyze the relationship between development and democracy only by the perspective of the existence or not of democratic elections is insufficient to solve the problem. It is perhaps essential to find methodological tools to ascertain the quality of democracy and institutions, evaluating the key between participation and contention. From this perspective, of a pluralistic nature, we have a new possibility to analyze the case. Przeworski, moreover, argues that democracies are not equal, and that institutional arrangements cause impacts to the sustainability of democracy (Przeworski, 2000, p. 128).

We can emphasize that, due to the numerous problems Haiti has faced in recent years, with a special focus on the political crisis, the climax of which was the assassination of then-President Jovenel Moïse, and the social situation in the context of the pandemic, there is an expectation that the United Nations will authorize a new peacekeeping mission. If this happens, there are speculations that the Security Council should coordinate the demands for establishing order and economical improvement with the promotion of democracy and the strengthening of political institutions.