Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.6 no.2 Medellín July/Dec. 2013

The effect of occupational meaningfulness on occupational commitment

El efecto de la relevancia laboral sobre el compromiso profesional

Itai Ivtzana,*, Emily Sorensena, Susanna Halonena

a Department of psychology, University of East London, London, England.

* Corresponding author: Dr Itai Ivtzan, Department of psychology, University of East London, Stratford Campus, London E15 4LZ, UK. Email: i.ivtzan@uel.ac.uk

Received: 06-05-2013-Revised: 23-10-2013-Accepted: 20-11-2013

ABSTRACT

Existing research lacks a scholarly consensus on how to define and validly measure 'meaningful work' (e.g., Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski, 2010). The following correlational study highlights the value of investigating meaningfulness in the context of occupational commitment. The study hypothesizes that occupational commitment is positively correlated with occupational meaningfulness, where meaningfulness is defined as the extent to which people's occupations contribute to personal meaning in life. One-hundred and fifty-six full-time office based UK workers completed an online questionnaire including 18 questions measuring levels of occupational commitment (Meyer, Allen & Smith, 1993), in addition to six novel items measuring occupational meaningfulness. The results supported the hypothesis and also showed that the affective sub-type of occupational commitment had the highest correlation with occupational meaningfulness. Such results exhibit the importance of finding meaning at work, as well as the relevance of this to one's level of commitment to his or her job. This paper argues that individuals should consider OM before choosing to take a specific role, whereas organizations ought to consider the OM of their potential candidates before recruiting them into a role. Possible directions for future research directions are also discussed.

Key Words: Personal Meaning, Occupational Meaningfulness, Occupational Commitment.

RESUMEN

La investigación existente carece de un consenso entre expertos sobre la forma de definir y medir válidamente "el trabajo significativo" (p. ej, Rosso, Dekas y Wrzesniewski, 2010). El siguiente estudio correlacional destaca el valor de la relevancia de la investigación en el contexto del compromiso laboral. El estudio plantea la hipótesis de que el compromiso laboral está correlacionado positivamente con la relevancia laboral, donde tal relevancia se define como el grado en que las ocupaciones de las personas contribuyen al significado personal en la vida. Ciento cincuenta y seis trabajadores de oficina de tiempo completo del Reino Unido completaron un cuestionario en línea, incluyendo 18 preguntas que miden los niveles de compromiso con el trabajo (Meyer, Allen y Smith, 1993), además de seis nuevos ítems que miden la relevancia laboral. Los resultados apoyan la hipótesis y también muestran que el subtipo afectivo de compromiso ocupacional tuvo la correlación más alta con la relevancia laboral. Estos resultados muestran la importancia de encontrar significado en el trabajo, así como la relevancia de esto para nuestro nivel de compromiso con el mismo. Este trabajo sostiene que los individuos deben tener en cuenta RL antes de elegir tomar un rol específico, mientras que las organizaciones deberían considerar la RL de sus posibles candidatos antes de contratarlos para una labor. También se discuten las posibles direcciones para futuras líneas de investigación.

Palabras Clave: Significado Personal, Relevancia Laboral, Compromiso Profesional.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, there has been increasing interest in the idea that meaningful work has a pivotal influence on workers (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009). This assertion is supported by a wide range of empirical research indicating, for example, that people who feel their work is meaningful report higher levels of job satisfaction, effort, and work unit cohesion (Sparks & Schenk, 2001); they are also said to have greater well-being in life (Arnold, Turner, Barling, Kelloway, & McKee, 2007), hardiness (Britt, Adler & Bartone, 2001), work engagement (May, Gibson & Harter, 2004), and to prize their work more than individuals who do not find their work meaningful (Nord, Brief, Atieh & Doherty, 1990). Moreover, studies concerning factors people believe to be personally important at work have indicated that one's job is an important source of personal meaning (Dik, Duffy & Eldridge, 2009; Penna, 2006).

However, a key problem in behavioral research has been the fact that 'meaningful work' can have a variety of connotations to researchers studying the concept (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009). In order to gain a practically useful accumulation of knowledge around a subjective concept such as meaningful work, there must be a measure of coherence, in ideological or methodological terms, to increase the collective validity of findings in this area of research. Hence, in an effort to clarify the type of meaning used in the present study, the definition of "meaningful work" has to be explored.

1.1. Defining meaningfulness in terms of its sources and experiences

In scholarly papers, the term 'meaningful work' can refer to either the sources or subjective experiences of meaningful work itself. A classic example of how meaningful work can be regarded in light of its sources is the Job Characteristics Model (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), which asserts that the presence of job characteristics such as skill variety, management style, task identity, and significance can cause the psychological experience of meaningfulness, which will subsequently affect people's work-related behaviours (Juhdi, Hamid & Siddiq, 2010; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). In other words, the focal points of this theory are the sources (job characteristics embedded in the job role) of meaning and their work outcomes (such as work engagement, job satisfaction, and productivity), whereas 'meaningfulness' is a subjective experience mediating these factors. After the introduction of the Job Characteristics Model (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), research on meaningful work has increasingly focused on measuring these proxies for meaningfulness (i.e. job characteristics and work outcomes) and less on finding ways to directly measure the subjective experience of meaningfulness (Steger, Dik & Duffy, in press).

The last two decades, however, have yielded a renewed interest in the investigation of the subjective experience of meaningful work, and this has led to more rigorous attempts to reach a scholarly consensus on the definitions of 'meaning' and 'meaningfulness' at work (Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski, 2010). 'Meaning' has been interpreted as ways in which workers make sense of their work (understanding of work role and tasks), whereas meaningfulness has been interpreted as the amount of personal significance people attach to their work or the psychological valence of work (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003; Ikiugu, 2005). The present study will focus on work meaningfulness - the positive sense of significance people experience with relation to their work.

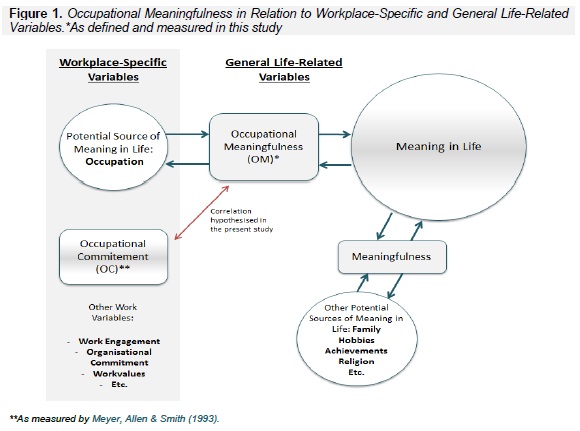

Despite these clarifications, there remains room for mixed interpretations of this positive sense of significance and how it relates to specific work as well as general life specific variables. This is important to clarify before considering methodological means of measuring meaningfulness, as leaving room for misinterpretations may cause problems in the comparison of results on meaningful work with other findings in this general area. A recent example of measuring work meaningfulness is presented by Steger et al. (in press) Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI), which is designed to tap into the full complexity of meaningful work. Though the WAMI appears to be a useful predictor of work-related behaviours, the words 'meaning' and 'purpose' sometimes remain ambiguous in terms of whether they relate to experiences that are felt only at work, or also to experiences of meaningfulness felt outside the workplace, as part of an overarching sense of meaning in life (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). The current study will aim to consistently avoid ambiguities related to this distinction, focusing on work meaningfulness with relation to how work provides meaningfulness in people's general lives, as opposed to people's workplace-specific sense of well-being (Figure 1).

1.2. Occupational commitment and meaningfulness

Businesses are experiencing increasing pressure to undergo organizational changes as a result of external economic crises or in order to keep up with technological developments (Dixon, Meyer & Day, 2010). As a result, organizations may be unable to provide the usual sense of job security that enables people to feel content within companies (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006) â hence employees may be less committed to their organizations and may subsequently transfer their commitments to their occupation (Carson & Bedeian, 1994; Irving, Coleman & Cooper, 1997; Laschinger, Leiter, Day, & Gilin, 2009). Currently, organizational commitment has been the most extensively studied form of work commitment (Joo, 2010), despite the fact that organizational commitment has been shown to have an independent effect on job involvement, job satisfaction, occupational commitment, and job performance (Lee, Carswell & Allen, 2000; Meyer et al., 1993). The acknowledgement of such a distinction is pivotal because these dimensions represent two qualitatively different work-employee relationships: a person-occupation relationship represents the interaction between a worker and his/her job role demands (Tubre & Collins, 2000), while a person-organziation relationship represents the interaction between a person and his/her organization (Shamir & Kark, 2004).

Evidence suggests that job roles hold a more personally significant importance to individuals than do other work-related variables, such as workplace environments (Ikiugu, 2005; Loscocco, 1989; Tubre & Collins, 2000). Previous research has highlighted the importance of meaningfulness in connection with a personal sense of attachment to one's occupation (Dik et al., 2009; Ikiugu, 2005; Juhdi et al., 2010). Dik et al. (2009) point out meaningfulness at work correlates positively with desirable career outcomes, as well as general well-being. This implies that meaningfulness is also correlated with occupational commitment. This relationship will be the focus of the current investigation.

Meyer et al. (1993) have constructed a reliable and widely-used measure of occupational commitment (OC) in the form of a questionnaire which taps into three distinguishable commitment sub-types: affective OC (i.e. intrinsic desire to stay in the occupation), continuance OC (i.e. perceived cost of leaving the occupation), and normative OC (i.e. experienced obligation to stay in the occupation). These dimensions, collectively called the Three-Component Model, have been differentiated from each other because they correlate with different work-related outcomes (Irving et al., 1997). This Three-Component model (and its accompanying scale) was originally used to conceptualize and measure organizational commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Because of the positive relevance between organizational and occupational commitment, Meyer et al. (1993) adapted the model and created a new scale to measure occupational commitment specifically. The model and its scale have been widely used in studies on occupational commitment (e.g. Irving et al., 1997; Snape & Redman, 2003; Stinglhamber, Benstein & Vandenberghe, 2002), and Meyer et al.'s (2002) meta-analysis supports the scale's effectiveness in bringing out consistent findings. Based on this, the current study uses OC to refer to occupational commitment and used Meyer et al.'s (1993) occupational commitment scale to measure it.

The overall construct of OC can be conceptualized as the sense of attachment workers feel towards their occupations. The sub-types of OC should be taken into consideration in research because of their different relationships to various work-related constructs. For example, affective OC correlates more strongly with organization-relevant outcomes, such as intention to leave the organization (Meyer et al., 1993) or job satisfaction (Irving et al., 1997), as compared with normative and continuance OC. Because Meyer et al.'s (1993) measure of OC has been widely used in research and relates to both person- and work-related variables (Lee et al., 2000), it seems a suitable measure of OC in the current study, where meaningfulness will be related to this construct.

In an attempt to disambiguate the word 'meaningfulness' in the context of occupational commitment, a definition of occupational meaningfulness (OM) specific to this study will guide the construction of questionnaire items measuring meaningfulness in relation to occupations. The use of the term OM will specifically denote the extent to which people's occupations contribute to their overarching sense of meaning in life (Figure 1). 'Meaning in life' (Steger et al., 2006) is seen as a single construct that can be affected by different sources, such as one's occupation. Previous indications suggest that individuals derive meaningfulness from a variety of sources, including personal projects (Powell, Moss, Winter, & Hoffman, 2002), relationships (Prager, 1998), and creativity (O'Connor & Chamberlain, 1996). Ikiugu (2005) discusses occupational meaningfulness through Royeen's (2003) chaos/complexity theory, proposing OM as a subset of meaning in life. Hence, relating a person's occupational role to his or her meaning in life (OM) could be contrasted with workplace-specific experiences of meaningfulness, which are only prevalent at work (Figure 1).

1.3. Rationale and hypothesis

The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between meaningfulness and OC, using a measure of meaningfulness intended to reduce the likelihood of misinterpretation. Since meaningfulness at work has been associated with desirable career outcomes and improved overall well-being, understanding the link between OM and OC could play a beneficial role for both individuals and organizations. It may help individuals to understand the implications of finding meaning through their occupations, and perhaps encourage them to more actively pursue it. It could also provide clarity to organizations on whether OM and OC are something they should invest in for their employees to explore. Based on the previous indication that workers value and attach meaningfulness to their occupations (Dik et al., 2009; Ikiugu, 2005; Juhdi et al., 2010), it is hypothesised that occupational commitment (OC) is positively correlated with occupational meaningfulness (OM). In other words, the more OM people experience, the higher their level of OC is predicted to be.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants and procedure

156 full-time office workers and professionals (age range = 19-64 years; mean age = 35.54, SD = 11.30, Median = 32.00), of various occupations and education backgrounds, in the United Kingdom, completed the questionnaire. Due to time constraints and access to participants, the inclusion criteria included being presently active in the workforce and having access to the internet to complete the survey. The most frequently listed occupations include various types of managers (42), directors (13), assistants (11), receptionists/secretaries (8), administrators (7), and estate agents (6). Eighty-seven questionnaire respondents were female.

Questionnaire respondents were a sample of volunteers who were sought via the researcher's existing contacts through professional networks. Potential respondents were either sent an email with a web link for the online survey or were given a sheet of paper listing the same link, enabling people to enter into their Internet browser. In all cases in emails, on information sheets, or via online forums – all respondents received a short description of the purpose of the survey, participant criteria, and contact details. They were given informed consent at the start of the study, were informed of their voluntary participation, and of their right to withdraw at any point in time. The research procedure and all participant facing materials were approved by University College London's ethical board.

2.2. Questionnaire construction

Twenty-four questions (18 measuring the OC variable; 6 measuring the OM variable) followed in a predetermined order that was uniform for all respondents. The 18 OC questions were taken from Meyer et al.'s (1993) study, and 6 of these measured affective OC (e.g. "I am enthusiastic about my occupation", "My occupation is important to my self-image"), 6 measured continuance OC (e.g. "I have put too much into my occupation to consider changing now", "It would be costly for me to change my occupation now"), and 6 measured normative OC (e.g. "I would feel guilty if I left my occupation", "I am in my occupation because of a sense of loyalty to it"). These were, collectively, representative of the overall variable OC referred to in the hypothesis.

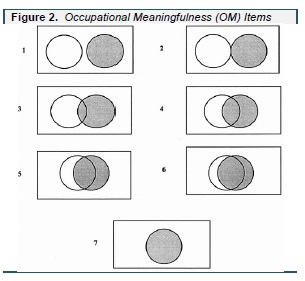

Additionally, 6 novel items (5 non-illustrated and 1 illustrated) were included to measure occupational meaningfulness (OM) (See figure 2). The OM items were carefully formulated to ensure that:

A) All of these used the word occupation rather than similar classifications, such as profession, career, or work, in order to avoid ambiguity (Blau, Paul & St. John, 1993; Meyer et al., 1993; Morrow, 1983).

B) The word occupation was consistently related to respondents' meaning or purpose in life. The emphasis on the latter is crucial because it clarifies that the words meaning and purpose refer to the definition of occupational meaningfulness, which examines how the occupation contributes to the presence of experienced meaning in one's life. By clearly and consistently relating one's occupation with one's meaning/purpose in life (i.e. overall life-related meaningfulness as opposed to workplace-specific meaningfulness), it should be possible to avoid analytical issues regarding participants' interpretation, on the form, of 'meaningful work.'

The five non-illustrated OM items were edited versions of the questions originally intended to measure a presence of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2006). By adding the relation between occupation and Meaning in Life (MiL), whilst retaining the same sentence structures, OM items were produced. The 18 OC items, and 5 non-illustrated OM items, required an answer on a 7-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (Absolutely Untrue) to 7 (Absolutely True), classified in words rather than numbers. The altered OC instrument indicated good test-retest reliability (Spearman's rho = 0.60, p < 0.01).

The illustrated OM item that was added to the questionnaire was a figure showing seven boxes, each containing one white and one grey circle, overlapping to different extents. This was originally used in a study investigating organizational identification (Shamir & Kark, 2004). The text accompanying the figure was a paragraph closely resembling the one used in its original context; instead of describing the circles as representing "you" and the organizational "unit", as described in the original study, the new paragraph describes one circle as representing "you doing the work you noted in question 4" (i.e. the respondent's occupation) and the other denoting "your meaning in life". Respondents were asked to identify the pair of circles that best illustrates the described OM relation, as applicable to their circumstances.

Non-Illustrated

1. I understand how my occupation contributes to my life's meaning.

2. My occupation gives me a clear sense of purpose in life.

3. I have a good sense of how my occupation makes my life meaningful.

4. I have discovered how my occupation gives me a satisfying life purpose.

5. My occupation does not make my life purpose clearer. (R)

Illustrated

This chart is intended to assess how much your occupational role makes your life meaningful.

Above you will find 7 rectangles. In each rectangle there are two circles. One represents you doing the work you noted in question 4, and the other circle is the meaningfulness you feel in your life. In each rectangle the circles are overlapping differently. In the first rectangle (number 1), they are totally separate and represent a situation in which you do not feel your work contributes at all to your meaning in life. In the last rectangle (number 7), the circles are totally overlapping and represent a situation in which you feel your work totally gives you a sense of meaning in life. Choose out of the 7 rectangles the one that most highly represents the extent to which your work contributes to your meaning in life.

RESULTS

3.1. Main findings

In order to test the hypothesis that occupational commitment (OC) has a positive linear correlation with occupational meaningfulness (OM), a correlational design was employed. The overall average of the 18 OC items was compared with a) the overall average of the 6 OM items (1 illustrated and 5 non-illustrated), b) the average of the 5 non-illustrated OM items, and c) the illustrated OM item in a Pearson regression analysis. All of these comparisons yielded significant moderate positive correlations (Table 1), confirming the experimental hypothesis that OM is positively correlated with OC.

3.2. Additional Findings

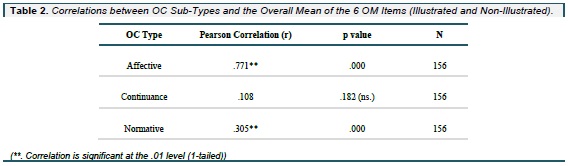

Explorative analyses on the data yielded important additional findings. Regression analyses were performed in order to test for the possibility that affective, continuance, and normative OC (each represented by 6 OC items) correlate to different extents with OM. Pearson regression analyses confirmed this to be the case (Table 2). Affective OC was most affected by OM scores, showing a strong correlation with OM. This was followed by normative OC, which yielded a moderate correlation. Finally, the correlation between continuance OC and OM was non-significant, implying that OM is not at all related to this type of OC.

DISCUSSION

As predicted, results confirmed the hypothesis that individuals' occupational commitment (OC) is positively correlated with their levels of occupational meaningfulness (OM). Both the illustrated and non illustrated OM items used in the measure showed relations with OC, resulting in an overall average of the 6 OM items as an acceptable independent variable in the analyses of the relationship with OC.

In this study, work meaningfulness was defined as a form of meaningfulness relating to the sense of meaning in one's life. As originally suggested by Ikiugu (2005), the above results confirm a relationship between work-specific factors and life- related experiences of meaning. Evidence of this link suggests that work meaningfulness is not only a construct that mediates workplace-specific job characteristics (Hackman & Oldham, 1976) but can also be an affective connection between a person's occupational role and general meaning in life. This implies that research on meaningful work would neglect the full complexity of meaningfulness if the focus remained entirely on indirect proxies of meaningfulness, such as work engagement (May et al., 2004). Rather, meaningful work research should take into consideration the extent of congruence individuals experience between their occupational roles and their meaning in life.

Additional analyses revealed that OM was highly correlated with affective OC and less so, but still significantly, with normative OC. This suggests that the level of OM influences people's intrinsic desires to stay in their occupations â data which employers should take into account in recruitment processes. Moreover, affective OC is a sub-type of work commitment with the strongest influence on work-related behaviors (Irving et al., 1997; Meyer et al., 1993), hinting that OM may exert substantial effect on whether workers choose to perform their jobs as best they can.

Results also revealed that continuance OC was not at all correlated with OM, as opposed to affective and normative commitment. This makes sense as continuance OC involves a concern for practical or objective matters surrounding the potential idea of leaving one's occupation (e.g. thoughts of whether there are alternative careers one could pursue), whereas the normative and affective forms of OC both involve considerations relating more to psychological concerns (i.e. concern of making the right decisions or satisfying a personal need for fulfillment) (Meyer et al., 1993). Similarly, OM is a highly subjective construct more psychological in valence than it is objective, so it is unlikely that this should be related to continuance commitment. In fact, the insignificant correlation between continuance OC and OM indicates that other non-affective factors have an influence within the broader construct of OC. Hence, when addressing the needs of employees low on OC, OM is only one of a variety of factors determining whether or not they would choose to stay in their occupations. The more comprehensive our knowledge of various influences on OC, the more informed we might be about causes of occupational turnover.

4.1. Methods to study OM

Having purely office based professionals as participants, limits the generalizability of this study findings, but still offers new, relevant insight to defining occupational meaningfulness. Future studies should explore OM beyond professional level workers and explore whether differences exist between types of professions. The current study's findings were also correlational, not causal, which means it is not possible to determine whether perceived OM is a cause or consequence of occupational commitment. A study with longitudinal design could explore whether a causal relationship exists, and exploring the impact the number of years one has spent in an occupation has on OC or OM will help clarify the relationship.

In addition to the promising uses of measuring OM, future studies ought to investigate this construct and its correlates further in order to increase the theoretical validity and usefulness of OM. Even though the altered OC instrument with the 6 new OM measures demonstrated good test-retest reliability, testing it further with a more varied population will strengthen its validity.

4.2. Implications

The emphasis in the present study was to define occupational meaningfulness (OM) in terms of its relation between occupational commitment and meaning in life, as originally indicated by Ikiugu (2005) and further explored here. The 6 OM measures and their significant correlation to affective OC demonstrate a clear connection between OC and OM. This simplifies the application of the findings to real-life occupational situations. Consistently asking about the same type of meaningful work (how one's occupation contributes to one's meaning in life) ensures that, for example, employers can ask this specific question when interviewing job candidates or assessing the root problems of employees who consistently under perform. When an employee's occupation does not appear to contribute to his or her sense of purpose in life, an employer can begin to question whether this person is suitable for the role or would benefit from being transferred to a role which contributes to greater personal significance for the individual.

An important potential consequence of this study is the ability to compare levels of OM between relevant populations. For example, businesses needing to determine which of their professionals require the most motivational attention could measure their employee's level of OM and identify employees who require additional meaningfulness added to their workplace-specific environment.

In addition to the promising uses of measuring OM, one might question whether or not OM can be induced in employees who already feel their occupations are meaningless. Employers might benefit more from transferring some employees to other roles rather than investing in training and motivational strategies to enhance commitment. Hence, testing for changes in levels of OM over time can prove a useful indicator of whether specific forms of meaning-making programmes or managerial influences can positively impact employees' levels of OM.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between occupational commitment and occupational meaningfulness, which was defined as contributing to overall meaning in life. The survey results produced a significant positive correlation, implying that occupational meaningfulness is a key consideration for individuals when choosing the appropriate occupation, and for organizations when choosing the right candidates for their roles. Despite the new use of the 6 OM measures, the scales indicated good test-retest reliability with this sample. Future research should aim to replicate the findings to strengthen its validity, as well as explore the potential causal relationship between the two variables through a longitudinal study with a wider array of professions.

REFERENCES

Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 193-203. [ Links ]

Blau, G., Paul, A., & St. John, N. (1993). On developing a general index of work commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42(3), 298-314. [ Links ]

Britt, T. W., Adler, A. B., & Bartone, P. T. (2001). Deriving benefits from stressful events: The role of engagement in meaningful work and hardiness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 53-63. [ Links ]

Carson, K. D., & Bedeian, A. G. (1994). Career commitment: Construction of a measure and examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 237-262. [ Links ]

Cartwright, S., & Holmes, N. (2006). The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review, 16, 199-208. [ Links ]

Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Eldridge, B. M. (2009). Calling and vocation in career counseling: Recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(6), 625-632. [ Links ]

Dixon, S. E. A., Meyer, K. E., & Day, M. (2010). Stages of organizational transformation in transition economies: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 416-436. [ Links ]

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250-279. [ Links ]

Ikiugu, M. N. (2005). Meaningfulness of occupations as an occupational-life-trajectory attractor. Journal of Occupational Science, 12(2), 102-109. [ Links ]

Irving, P. G., Coleman, D. F., & Cooper, C. L. (1997). Further assessments of a three-component model of occupational commitment: Generalizability and differences across occupations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 444-452. [ Links ]

Joo, B. K. (2010). Organizational commitment for knowledge workers: The roles of perceived organizational learning culture, leader-member exchange quality, and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 69-85. [ Links ]

Juhdi, N., Hamid, A. Z. A., & Siddiq, M. S. B. (2010). The effects of sense of meaningfulness and teaching role attributes on work outcomes - using the insight of Job Characteristics Model. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 2(5), 404-428. [ Links ]

Laschinger, H. K. S., Leiter, M., Day, A., & Gilin, D. (2009). Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: Impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management, 17, 302-311. [ Links ]

Lee, K., Carswell, J. J., & Allen, N. J. (2000). A meta-analytic review of occupational commitment: relations with person- and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 799-811. [ Links ]

Lips-Wiersma, M., & Morris, L. (2009). Discriminating between 'meaningful work' and the 'management of meaning'. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 491-511. [ Links ]

Loscocco, K. A. (1989). The interplay of personal and job characteristics in determining work commitment. Social Science Research, 18, 370-394. [ Links ]

May, D. R., Gibson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 11-37. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualisation of organisational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualisation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78 (4), 538-551. [ Links ]

Morrow, P. C. (1983). Concept redundancy in organizational research: The case of work commitment. Academy of Management Review, 8(3), 486-500. [ Links ]

Nord, W. R., Brief, A. P., Atieh, J. M., & Doherty, E. M. (1990). Studying meanings of work: The case of work values. In A. Brief & W. Nord (Eds.). Meanings of occupational work: A collection of essays. Lexington: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

O'Connor, K., & Chamberlain, K. (1996). Dimensions of life meaning: A qualitative investigation at mid-life. British Journal of Psychology, 87, 461-477. [ Links ]

Penna (2006). Meaning at Work. Research Report. Retrieved from http://www.penna.com/research/Detail/meaning-at-work [ Links ]

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviours: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 327-340. [ Links ]

Powell, L. M., Moss, M. S., Winter, L., & Hoffman, C. (2002). Motivation in later life: Personal projects and well-being. Psychology and Aging, 17(4), 539-547. [ Links ]

Prager, E. (1998). Observations of personal meaning sources for Israeli age cohorts. Aging and Mental Health, 2(2), 128-136. [ Links ]

Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton, & R.E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 309-327). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. [ Links ]

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. [ Links ]

Royeen, C. B. (2003). Chaotic occupational therapy: Collective wisdom for a complex relationship. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(6), 609-624. [ Links ]

Shamir, B., & Kark, R. (2004). A single-item graphic scale for the measurement of organizational identification. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 115-123. [ Links ]

Snape, E., & Redman, T. (2003). An evaluation of a three-component model of occupational commitment: Dimensionality and consequences among United Kingdom human resource management specialists. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 152-259. [ Links ]

Sparks, J. R., & Schenk, J. A. (2001). Explaining the effects of transformational leadership: An investigation of the effects of higher-order motives in multilevel marketing organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 849-869. [ Links ]

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. (in press). Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment. [ Links ]

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80-93. [ Links ]

Stinglhamber, F., Benstein, K., & Vandenberghe, C. (2002). Extension of the three-component model of commitment to five foci: Development and measures and substantive test. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 123-138. [ Links ]

Tubre, T. C., & Collins, J. M. (2000). Jackson and Schuler (1985) revisited: A meta-analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conflict, and job performance. Journal of Management, 26(1), 155-169. [ Links ]