1. Introduction

This research seeks to contribute to closing the existing gap in the relation university-business and the ethical gaps in the educational system, as reflected in the National Youth Survey (Colombia Joven, 1972). This research is developed within the generic competences of the Tuning Proyecto Tuning (2004), its replica for Latin America (Tuning-Alfa, 2007) and the Productive Transformation Program of Colombia (2009). The university distance from the industrial and technological growth processes is caused by different factors, such as the business sector’s lack of interest, the weak integration and the scarce budget for R&D assigned by entrepreneurs. The comparison indicates that in countries like Chile, 56% of the researchers work for companies, 34% for universities, and 4.1% for the government. In Colombia, the percentages are 2.5%, 80.5% and 8.7%, respectively (Herrera et al., 1994). Despite the high concentration of researchers in academy, the business sector needs are not being solved effectively.

Insufficient development of labor competences is also another limiting factor for sustainable growth. According to Colombia’s National Planning Department, the effort to innovate and the highly qualified human capital are concentrated on the large and medium-sized companies of the manufacturing industry; 83% of the spending on innovation and business development is concentrated on them. Half of the personnel employed in the manufacturing industry bears high-school education, 16.2% elementary education, 9% possesses technical education, 12.2% undergraduate education and 0.3%, bears master’s and doctoral training.

Thus, the country’s offer of highly qualified human capital is limited. In 2008, Colombia had 3.7 doctors per million inhabitants; however, this figure was 327 in the United States (DNP, 2011). Globalization and the accelerated changes in ICTs reveal the low educational levels of Colombian managers and administrative staff (Caballero, 2001).

According to the World Economic Forum (2014), Colombia has stagnated in recent years, occupying the 68th position in 2010 and 2011, the 69th position in 2012 and 2013, moving to the 66th place in 2014 (WEF, 2014), and 61 in 2015 (WEF, 2016). Its efficiency in the labor market and its technological developments are below those from Mexico, Peru, Chile and Panama; corruption, delays in infrastructure works, government bureaucracy, poor access to financing, high interest rates and crime rates, increase country risk (Delgado, Sánchez, & Vélez, 2016). They also demand educational transformation, social innovation (Tunning América Latina, 2013), and the improvement of management in World Class Sectors (DNP, 2011).

1.1 The Modern Origin of the Concept of Competence

In the 1940s, the pressure from the scientific-technical development required the individual and organizational psychology to generate new applied knowledge (Mayo, 1945); competences such as motivation, leadership, teamwork, among others are proposed (Dávila & de Guevara, 2001). Chester Irvin Barnard (1959), concerning the role of an executive, contributes with his cooperative systems theory; he stated that, “to achieve the objectives people do not act alone, but relate. Organizations arise through cooperation and the participation of people” (Rivas Tovar, 2011, p. 11). Thus, psychological factors and limitations in the purposes determine efficiency or inefficiency (Barnard, 1959). For Parsons (1951), the achievement of goals and the skills attributed are mechanisms to assess people for their accomplishments rather than for their qualities (Zapata Cantor, 2014). McClelland (1973) proposed competences as deeper alternative to the traditional measurement of intelligence (Galindo Pinzón, 2005). R. Boyatzis (1982) considered that competences are permanent qualities over time and are causally related to good or excellent performance in the fieldwork. Today, competences are considered as capacities or abilities; series of related and different behaviors (conducts), organized around intentions over time (R. E. Boyatzis, 2008).

In cognition psychology, learning is a fundamental factor and the subject is the process’ core. Competences, therefore, constitute the language’s theoretical and practical knowledge in everyday life (Chomsky, 2011); it is a relation between knowledge and know-how, the ability to create new things from a critical perspective through learning and accommodation (Piaget, 1978). Superior psychological processes generated socio-historically in a community and cultural way (Vigotski, 1978); metacognition that makes it possible to reflect on knowledge and potentials; regulation of actions and recognition of socio-environmental contexts from values, attitudes and perceptions (Ausebel, 1994). According to Gardner (as cited in Tovar Galvez, 2008), competences are multiple intelligences needed to solve problems and create products in community and cultural contexts. Structuralism is overcome through processual approach; a leap from content to cognitive processes that range from logical operations to contextual relationships (Organista, 2000).

Competences are characterized by a visible conceptual inaccuracy. According to Clark (as mentioned in Pertegal Felices, 2011), this is due to the lack of empirical foundations in their definition, to different uses and to culture. Based on studies such as that of Repetto and Pérez Gonzalez (2007), three model perspectives can be identified to refer to competence as behaviorist (McClelland, 1973) (performance according to a list of tasks), as qualities or attributes (Royo & Del Cerro, 2005) (successful performance traits), and as holistic (Vargas, Casanova, & Montanaro, 2001) (the integration of tasks and attributes in an assertive manner according to contexts). Simultaneously, the term “competences” has been approached from the performance associated to the competitiveness perspective (Tejeda Díaz, 2011).

1.2 The Tuning Project

The university-business cooperation affects labor insertion (Pertegal Felices, 2011), and for this reason is necessary to modify the learning systems, standardize programs, and strengthen academic communities in terms of building a multidisciplinary international network culture (González Jaimes & Salgado Vargas, 2016). However, this project faced several manifestations of rejection by principals and students (Campos Rodríguez, 2011). Several statements (the ones from Lisbon in 1997, Bologna in 1988, Sorbonne in 1998 and Bologna in 1999) (Menéndez Varela, 2009), seeking for the transformation of teaching practices focused on learning, knowledge, understanding and skills for action, and existence were rejected. Nevertheless, career areas were mapped (2000-2002), generic and specific competences were established (20032004), and, finally, the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) to facilitate mobility and homologation (2005-2008) was created.

Facing Europe’s challenges of knowledge economy (Consejo-Europeo de Estocolmo, 2001), the project focuses on structures and contents of studies, competences, employability, citizenship, and exchange under the concept of competence, understood as a dynamic combination of attributes, in relation to procedures, abilities, attitudes, and responsibilities (Bravo Salinas, 2007). According to González and Wagenaar (2003) (as cited in Pertegal Felices, 2011) competences are transversal (cognition, technology, methodology and linguistics), interpersonal (personal aspects and social factors in the sense of cooperative interaction), and systemic (skills conceiving systems as a whole).

1.3 Tuning-ALPHA

In the Latin American version (ALFA-Latin America Academic Training), employers are linked with a contextualizing desire; quality is conceived as transparency, adaptation of educational objectives, response to beneficiaries, and sense of relevance (Campos Rodríguez, 2011). The generated debate promoted the development of quality, efficiency, and (Tuning-Alfa, 2007; Tunning América Latina, 2013). This notion of competence overcomes traditional models of education and labor certification, as Gomez proposes (as mentioned in Rodríguez Zambrano, 2007).

In 2008, Colombia established common references and identified four generic competences for higher education, such as “Communication in Mother Tongue and a Foreign Language, Mathematical Thinking, Citizenship and Science, Technology and Information Management” (MEN, 2009, p. 13) . The articulation of education to the productive sector is promoted so that the neoprofessionals respond to the labor market (MEN).

The research work by ASCOLFA-GRIICA, based on Bédard (2003), shows that in our context, epistemological and praxeological competences are privileged; this helps orienting the construction of curricula, recruiting processes and professional performance evaluation (Lombana, Cabeza, Castrillón, & Zapata, 2014), as well as the most relevant generic competences (Castrillón, Leonor, & Lombana, 2015). A research developed in the Colombian Caribbean context identified competences such as the strategic, tactical, and operational approach (Daza Corredor, Charris Fontanilla, & Viloria Escobar, 2015).

Knowledge is one of the most decisive competences despite the little evidence on skill-related competences (Toro, 1997), on intangible assets management such as the intellectual capital (Araujo, Barrutia, Hoyos, Lan- deta, & Ibañez, 2006), the leadership styles (Alacon & Arango, 1994), capabilities and resources (Martínez Santa María & Araujo de la Mata, 2010), and financial results (Thompson, Peteraf, & Gamble, 2012). Today’s manager must have comprehensive competences in international contexts (López Rodriguez, 2016).

2. Methodology

This research is correlational-causal and it measures the competitiveness level of the World-Class Companies in Colombia. This is based on the level of motivation and self-efficacy of the generic competences developed by the Tuning Project for Latin America. The dependent variable is the managers and administrative staff’s competitiveness, understood as the ability to do something right. This activity allows the accumulation of experience that can later be reflected in costs, thus, evidencing the efficiency of an area, a discipline or a function (Thompson Jr. & A., 2008). The independent variable is the generic competences. It refers to an integral formation of citizens; a set of capacities to solve a given problem within a specific and changing context (Tunning América Latina, 2013).

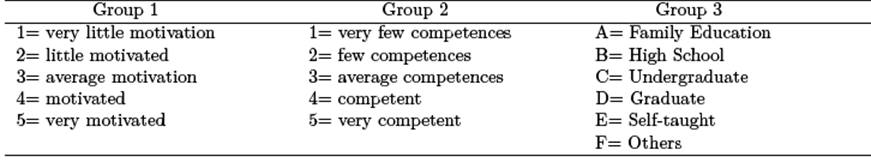

We used psychometric techniques with a rating scale of 1 to 5 for the first two groups or categories: MotivationCommitment and Self-efficacy. For the third group, we studied the origin of the competence by using letters: from “A” to “F” (Rodriguez, Olmos, & Martínez, 2012). Table 1 details the rating scales for each of the three groups or categories.

The sample population is constituted by managers of some of the 16 economic sectors of the country, distributed in services, manufacturing, and agro-industry. Table 2 shows the activities performed by that population and the number of existing companies, according to the information provided by the sources described in column 3.

A survey was applied to 280 managers to evaluate the 27 generic competences proposed by the Tuning Project. As it can be observed, activities like the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO), the metallurgical, the automotive spare-parts sector, the health and wellness tourism, the cosmetics, and the cleaning sectors were not considered since the samples were very small. Nature Tourism, fashion, and textiles were taken into account. The last column of the previous table corresponds to the population size, whose total is 695 companies, according to Table 3.

The most relevant competences were identified in the managers and administrative staff’s performance. They were found through descriptive analysis techniques for nominal variables and the use of sector graphs, bar and frequency graphs, and some contingency tables with the SPSS software. By means of exploratory factor analysis and validity tests, the main components were extracted. The matrix of components and rotation of the factors were calculated thanks to the Varimax Method.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive Analysis

The 27 competences were grouped by type, as shown in Figure 1. Since they are generic competences, they focus more on doing (capacity and ability) than on knowledge.

3.1.1 Motivation-Commitment and Self-Efficacy

The results indicate that more than 83% are motivated and committed to their organizations, and none of them show little or no commitment, neither are they discouraged. The Self-efficacy results reflect a different composition from Group 1. These managers have little or very little competences; however, the greater weighting (41.67%) corresponds to Regular Competences. 58% of Colombian managers have good or very good competences for the development of their general functions; the rest of them need to improve their levels. The motivation of Colombian managers and administrative staff is greater than their own ability to be more competitive.

3.2 Analysis of Averages and Comparison between Means

Table 4 compares the average to validate the findings. It indicates that for groups 1 and 2, with a general average of 4.43 and 4.1 respectively, the motivation is higher than the level of effectiveness they have in the performance of their functions.

The average value of 2.44 in Self-efficacy indicates that the managers and administrative staff have little or no ability to communicate in another language. The foreign language score (3.31) shows little ability to work in international contexts and understand the dynamics of globalization according to Tuning-Alfa (2007).

The ethical commitment and the one to quality are the two most important competences that a manager should have. Even though reality is contradictory, since “bribery is still the most widespread practice when doing business since 62% of businessmen perceive that if bribes are not paid, business is lost” (Transparencia por Colombia, 2013, p. 93).

3.3 Origin of Competences

It shows a managerial profile, with an undergraduate academic education; professions related with administrative sciences and engineering predominate. Graduate studies majoring in administrative sciences and the absence of Master Degrees and Ph.Ds. prevail.

With regard to the origin of each of the 27 competences, family and undergraduate training are highlighted, as shown in Figure 2.

58% of the competences are related to the family and undergraduate education; high school education is not representative in the manager’s background for their performance; 16% of the competences are self-taught. Only 5% of them has a graduate degree.

3.4 Factorial Analysis

Analyses by factors create a new set of uncorrelated variables (underlying factors), from a set of correlated variables in such a way that they allow a better understanding of the data and new associations between the variables.

The initial results showed a determinant of 1.27x10-12, close to zero, indicating that the matrix is not equal to the identity matrix. The Chi Square distribution for the Bartlett Sphericity Test showed a significance level of less than 0.05, thus the null hypothesis is rejected and confirms again that the correlation matrix is not equal to the identity matrix. The Chi Square distribution for the Bartlett Sphericity Test showed a significance level of less than 0.05, thus the null hypothesis is rejected and confirms again that the correlation matrix is not equal to the identity matrix. However, the value of 0.357 in the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test is a not suitable value for factor analysis. Thus the following eight competences with the lowest correlations were excluded.

Ability to act in new situations.

Ability to identify, pose, and solve problems.

Research ability.

Commitment to quality.

Commitment to the preservation of the environment.

Commitment to their socio-cultural environment.

Ethical commitment.

Ability to work autonomously.

All commitment competences have little relation with the competences of capacity, ability and knowledge, in spite of the fact that the “commitment to quality” and the “ethical commitment” scored the highest in the descriptive analysis. It is inferred that little knowledge, skills, and abilities are required to effectively manage an organization’s quality of processes, products, and services. Table 5 shows the results of the initial tests that validate the procedure.

According to this, the model is valid since the correlations matrix of the 19 competences resulting from the purification is different from the identity matrix.

For values greater than 1, there are six main components, since from the seventh component the results are lower (component 6=0.963) in the “Total” column. The column “variance’s %” indicates that the first component explains 37.155% of the data variability; the second component explains 10.359%. The “accumulated %” indicates that the six main components are explaining 73.373% of data variability, which is a significant value for the research’s purposes (Figure 3).

3.5 Component Matrix

The Component Matrix is evaluated in order to identify which competences are grouped in each of the factors. Table 7 shows the list of the 19 competences with the value of their respective values obtained from the SPSS.

The first factor consists of the first 13 competences with high correlations among them and a higher load value. The second consists of the next three and the third factor includes the last two competences. From competence 14 (Respect for Diversity and Multiculturalism), the load value in Component 2 is higher.

3.5.1 Rotation of Factors

This procedure intends that the largest number of possible loads is close to zero and maximize the others. The method used for the rotation was Varimax with Kaiser normalization and the results are presented in Table 8, where they converged after nine interactions. Based on the correlation level in the previous table, the result of the factor analysis suggests to group the 19 competences into six main components or factors.

The first factor brings together the first five competences, which combine the ability to create, communicate, and criticize based on knowledge. In fact, they were grouped under the name of “learning”. When comparing the results of this factor to the Tuning Project, there is an important level of consistency between both studies, since the latter group includes nine competences and the present research comprises the same ones (except for the Creative Capacity). In this sense, the results also converge with Tuning Project in the Social Responsibility and the Citizen Commitment competences. The second factor is made up of capacities associated with mental processes that allow arguing, making decisions, and planning future actions through projects; these are grouped in the “Reasoning Factor”, as shown in Table 9The third component, called “Leadership and social values”, compiles three competences that mix basic elements of management, such as leadership, motivation and teamwork, with social responsibility, and citizen commitment.

Factor 4, “Interpersonal skills and ICT”, is a mixture of skills to research, use ICTs, and personal relationships with the ability to communicate in a foreign language.

Factor 5, “Time Planning and Knowledge Management”, refers to the efficient use of time and the ability to apply knowledge.

Factor 6, “Global Thinking”, corresponds to respect for multicultural diversity and the ability to work in international contexts.

4. Discussion

The generic competences model, Tuning, is proposed from an educational sociology approach. It intends to revolutionize educational systems, not from an integralethical education perspective but from the tuning-in with companies’ viewpoint (based on the homogenization of syllabuses in terms of teaching, learning and evaluation), that is to say, these competences have an economic background (Menéndez Varela, 2009), which questions university autonomy. The project does not contemplate the tuning-in of companies with universities but vice versa, since the graduates’ profiles and the learning outcomes do not go beyond employment. Given this situation, the sense of having universities as the centers of knowledge can be questioned.

The challenge universities face, based on the expectations generated by the Tuning project, is to train highly disciplined professionals, that is, experts in the domain of their disciplines with transversal competences that allow them to face the contextual changes of work and of existence (Olivares et al., 2018). In this sense, it is not possible to ask about the scope of curricular designs and redesigns while the emphasis on their contents still prevails.

Professionalization, understood as a training process within the different disciplines, is not enough in front of the challenges of knowledge and performance. As the frontiers of science have been broken, it is also necessary to train people to make them capable of working in transdisciplinary fields (this is the demand generated by the dynamics of today’s problems). Weaknesses in social skills are well known (Muñoz-Osuna, Medina Rivilla, & Guillén Lúgigo, 2016) as well as the great tendency towards hard competences, oriented to technical-practical tasks. Facing these realities, it is necessary for universities to review curricular innovation processes, since such competences are essential, especially at the level of managerial decision-making.

Despite the national government’s interest in incorporating the Productive Transformation Program into its strategic lines, its 20 World Class Sectors have not been able to achieve the expected results. In this sense, the National Administrative Department of Statistics (2017) says that between 2013 and 2017 non-traditional exports went from 17,000 to 13,588 million dollars (FOB). This shows, among other aspects, the limitation of speaking a foreign language and the lack of global thinking of managers.

On the other hand, the systematic review of university curricula for the training of managers indicates that they do not focus on the strengthening of managerial competences. In this way, this research coincides with Marín, Michelsen, and Ospina (2008) by stating that companies do not communicate to academy their need to train managers in certain skills, nor do universities adequately train their professionals in the requirements of the labor supply to achieve superior performance. Indeed, the commitment of universities and the State towards the improvement of higher education is essential; it should be aimed at strengthening the culture of innovation, greater use of ICTs, and the consolidation of productive alliances with the business sector to solve the structural problems of the World Class Sectors.

Based on Bédard (2003), the results coincide with Lombana et al. (2014), when affirming that in the pro esses of academic formation in higher education, epistemological, and praxeological competences are privileged, while ontological competences are poorly developed. This leads to a poor development of the others. In the same sense, both studies also evidence the need for developing the latter (ontological) competences from the first years of life within the family and during the elementary education years, aspects that would be perfected during the university years and working life.

Other nuances of the weak university-enterprise relationship are also proposed for discussion. Universities, due to their “market focus”, are forced to behave like a company and incorporate into their strategies reduction of costs, low prices, or quality of service. risking the generation and transfer of knowledge and technology towards the productive sector (Espinoza, 2017). The second is incapable of structuring organizational forms, demanding highly competent managers and administrative staff. The above, in addition to the few funding for science, technology, and innovation, leads to low levels of competitiveness in international markets.

5. Conclusions

In the training of skills, undergraduate programs predominate as the source providing the most competences. Nevertheless, some results are striking. For example, 36% of managers learn to communicate in a foreign language during high school. The third part of them develops themselves, the capacity for criticism and self-criticism; on the other hand, the creative capacity develops almost in the same proportions within the main sources, such as family (22%), school (17%), university years (25%), and self-learning (25%), while in postgraduate studies it is null. This behavior is similar for the ability to work as a team.

The skills were developed while studying undergraduate programs, except the interpersonal and autonomous work that are formed within their family. The high school years and the graduate studies are the sources that contribute least to this type of training.

The competences related to commitment, responsibility, and respect are highlighted by being taught from family, training for two thirds of managers. Knowledge competence is acquired by 58% of managers while studying their undergraduate programs, 22% in their families, and 8.3% are self-taught.

The results, consistent with the Tuning study, allow us to conclude that family education is one of the main sources of competences, especially those related to the being, such as responsibility, commitment and respect.

The ability to communicate in a foreign language and the ability to work in international contexts are the weakest competences.

Consequently, in order to improve the level of competitiveness of managers and executives in World Class Companies, it is recommended to encourage graduate training with more comprehensive curricula that includes six factors in their curricula: learning, reasoning, leadership, social values, interpersonal and ICT skills, knowledge transfer, and global thinking.