1. Introduction

Psychosocial risks refer to those aspects of work design and management and the social and organizational context, which are likely to affect well-being as well as physical, mental, and social health. According to the European Agency for Safety & Health at Work (2007), the psychosocial risks that most impact people’s health are stress at work, violence, and workplace harassment or mobbing (Brun & Milczarek, 2007).

Since Heinz Leymann (1990) introduced the term workplace harassment in 1990, many definitions of the term finally coined as mobbing have been made. Piñuel and Zabala (2001) related workplace harassment

with the aim of intimidating, diminishing, reducing, flattening, intimidating and emotionally and intellectually consuming the victim, with a view to eliminating him/her from the organization or satisfying the insatiable need to attack, control and destroy that the harasser usually presents, which takes advantage of the situation offered by the particular organizational situation (reorganization, cost reduction, bureaucratization, dizzying changes, etc.) to channel a series of psychopathic impulses and tendencies1. (p. 55)

Hirigoyen (2001) defined workplace harassment as “all abusive behaviour (gesture, word, behaviour, attitude...) that attempts, by its repetition or systematization, against the dignity or mental or physical integrity of a person, endangering their employment or degrading the work environment” (p. 41). This means that workplace harassment is workplace violence (WPV) in small doses that have a great destructive capacity. People who suffer from it are deeply destabilized. The characteristics common to these behaviours imply repetitiveness (e.g., with a weekly frequency) and must be prolonged in time (e.g., at least six months). Another particularity is the difficulty that the worker who is the object of the animosity encounters in defending himself/herself, always observing a clear difference in power in favour of the aggressor (Einarsen & Mikkelsen, 2002). The different hostile behaviours take place within the framework of a work relationship, but they do not respond to the organizational needs of the latter; the purpose is to create a hostile or humiliating environment that disrupts the victim’s working life and is both an attack on the dignity of the worker and a risk to their health. It is a model of aggression that varies according to sociocultural circumstances; the higher one goes up the sociocultural scale, the more sophisticated, aggressive, and difficult to notice these aggressions are.

Workplace harassment has been given many labels, including bullying, harassment, workplace violence, mobbing (Schindeler, 2013) and discrimination (Newman et al., 2011). All these concepts are unified in this article as workplace violence (WPV), which will be treated as equal concepts.

Currently, workplace harassment or mobbing is one of the most worrying risk factors in organizations, given its relevance and negative impact on the health of workers (Sancini et al., 2012). According to the Cisneros xi barometer, in Spain 13.2% of the working population experiences workplace harassment and 21% has suffered it throughout their working life (Instituto de Innovación Educativa y Desarrollo Directivo, 2009).

Sometimes WPV can be confused with stress, pressure at work or even with the existence of conflicts or disagreements with other people in the organization. As Leymann and Gustafsson explain (1996), moral harassment is more than stress, even if it goes through a stage of stress. Stress is destructive if it is excessive. However, bullying is destructive by its very nature. Harassment is far from being an interpersonal conflict, it is an abuse and should not be confused with legitimate decisions that arise from the organization of work. According to the author, the so-called “management mistreatment”, sporadic aggressions, poor working conditions or professional coercion are not considered harassment.

The negative effects that workplace bullying causes on health come from both the personal characteristics of the worker and the work environment (Vie et al., 2012). The authors showed that self-labelling, the belief that a person has that they are effectively the object of bullying and that leads them to recognize themselves as victim, plays a moderating role between exposure to bullying behaviours and health consequences. In summary, the results of different investigations suggest that individual characteristics are important when reacting to possible situations of workplace harassment and can explain, at least partially, the effects on health.

It has also been shown in the healthcare sector that an increase in WPV has a significantly negative influence on job satisfaction. Frequent exposure to violence at work causes greater vulnerability in people, which translates into increased anxiety, nervousness, fearful and full of negative emotions. All this ends up causing a great distraction from the work itself, which makes it difficult to achieve their professional and personal goals, and results in a decrease in job satisfaction (Zhao et al., 2018). It is also known that job engagement is an essential factor of thriving at work and is a very valuable asset to overcome the difficulties of the environment. People with vitality are not susceptible to anxiety and depression (Vinje & Mittelmark, 2008).

In the scope of this study, WPV, discrimination, psychological, physical, and sexual violence are analysed. Regarding sexual violence, it is known that people who have reported being victims have significantly lower levels of job satisfaction, engagement, and performance. A-long with a greater tendency to leave the workplace, suffer work stress and physical and psychological problems than those who were not harassed (Chan et al., 2008).

1.1 Psychosocial Risk Factors and Workplace Violence

According to Hirigoyen (2001), WPV appears more easily in work environments subject to stress, with poor communication and lack of recognition at work. Recent studies show that in organizations where job insecurity prevails, situations of harassment can appear more easily due to the presence of hypercompetitive attitudes, the control of the impressions that other colleagues have of us and the narcissistic leadership style (Palma-Contreras & Ansoleaga, 2020). According to Song (2021), there is a causal relationship between psychological anxiety about losing a job and the intention of bullying (Song, 2021).

Factors such as time pressure, workload, and communication have been shown to be of great importance in the risk of WPV, suggesting that poorly organized workplaces may be more prone to experiencing psychosocial problems such as violence and harassment (Bentley et al., 2014; Skogstad et al., 2011; Zahlquist et al., 2019).

Figuereido-Ferraz (2012) demonstrates the existence of a significant relationship between interpersonal conflicts and WPV, while some labour resources such as social support and role clarity act as protectors against this WPV.

Evidence has also been found that workers’ perception of psychosocial risk factors is a good predictor of well-being at work. Observing that high levels of satisfaction and motivation are correlated with low levels of perceived stress (Luceño-Moreno et al., 2017).

1.2 Differences between the Sexes

From the scientific literature analysed, it has been observed that most research on sexual harassment is more focused on the group of women than on men. In fact, according to a recent study of Canadian public employees, women are 2.2 to 2.5 times more likely to experience workplace discrimination and harassment than their male counterparts (Waite, 2021).

Some researchers propose that this is because men may perceive sexual harassment as a compliment or as something reciprocal, so that sexual harassment would not pose a threat to them (Cochran et al., 1997). This could be the reason that men report fewer cases of harassment or even come to accept them (Berdahl et al., 1996).

Instead, other authors have reported significantly higher values in WPV in men compared to women. Although when analysed in detail, it is observed that for the dimension of sexual harassment the values are higher in women (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2016; Guay et al., 2016).

To better understand the differences between the sexes, we must also analyse the origin of sexual harassment. In this sense, we know that, for both men and women, sexual harassment is significantly related to various physical and psychological outcomes of work (Harned & Fitzgerald, 2002). Nevertheless, the physical and mental impact may not be the same between the sexes. Some studies show that the relationship between sexual harassment and depression is greater in men than in women (Street et al., 2007). Nevertheless, in a systematic review on the physical and psychological effects of harassment, no significant differences were observed between the sexes (Chan et al., 2008).

With the advent of social media, a new form of WPV has emerged, called cyberbullying. Recent studies show that women have a higher perception of cyberbullying than men, especially as women experience widespread online harassment, including insults, stalking, aggression, threats, and non-consensual sharing of sexual photos (Im et al., 2022).

1.3 Differences between Age Groups

Research on how we respond to threats of bullying according to age is related to coping with stress. In this sense, some authors report that older people have a better capacity to regulate the negative effects of stress than young people (Carstensen, 1995). Although there is not a large age difference in the implementation of problemfocused strategies (e.g., eliminating the source of the problem), when faced with everyday stressors, middleaged people seem to use more proactive strategies focused on emotions that young people (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2004).

Proactive emotion-focused coping involves directly confronting negative emotions caused by stressful events to control them (e.g., reflecting on one’s own emotions). Because personal and environmental constraints often prevent harassed workers from taking effective confrontational action (Fitzgerald et al., 1995), the tendency of middle-aged people to deal with the situation through psychological means can help regulate its impact on workrelated problems, both psychologically and physically.

There is another point of view that should be considered regarding the moderating effect that age can have on workplace and sexual harassment, and it is related to the greater dependence that older people have on their work and perceived employability. Harassment may be perceived as a threat to maintaining employment income, potentially negatively affecting job security, employment status, promotion prospects, and interpersonal support system (Lundberg-Love & Marmion, 2003).

Older people generally require more job security and regularity than younger people, as they have greater family and financial responsibilities (Finegold et al., 2002), and perceive a lower level of occupational mobility (Kuhnert & Vance, 2004). According to this perspective, sexual harassment can have greater impact on older people than on younger people. However, the greater ability to confront negative emotions that older people have seems to give them greater resistance to the negative effects of bullying (Lim, 1996). That is why the consequences of bullying seem to be more negative in young people (Chan et al., 2008).

It should be noted that there are authors who have not found significant differences between the different age groups (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2016). In contrast, other authors identify the age group of 18-25 years as the one with the lowest perception of WPV (Guay et al., 2016), so the role that age plays in the perception of WPV is not very clear.

1.4 Differences between Seniority Groups

In a recent study carried out during the Covid-19 pandemic in healthcare workers, it was observed that seniority lowers the chance of being exposed to WPV (Dopelt et al., 2022). Numerous studies show that professional experience improves the ability to manage conflict situations with angry patients (Li et al., 2018; Shapiro et al., 2022; Sharipova et al., 2010).

1.5 The Present Study

Based on the previous studies analysed, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H 1. The perception of workplace violence (WPV) increases with psychological risks.

As it has been observed in all the literature analysed, it is expected that there is a significant relationship between psychosocial risks and the perception of WPV.

H 2. There are differences in the perception of WPV according to sex, with women having a higher perception compared to men.

Most of the literature analysed places the group of women with the highest probability of suffering WPV, especially that related to sexual violence. Although some authors have observed that they obtain results where the perception is significantly higher in men (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2016), in general it seems that there is a greater consensus that the female sex is the one that is most exposed to WPV.

H 3. There are differences in the perception of WPV according to age, with younger people being the ones who will perceive more WPV.

The literature analysed is not very conclusive about the effect of age on WPV. Some authors have not found significant differences between the different age groups (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2016). However, age plays an important role in regulating emotions such as stress, and the greater experience and autonomy of older people seems that can play a protective role against situations of WPV.

H 4. There are differences in the perception of WPV according to seniority in the company, with people with less seniority being the ones who will perceive more WPV.

If age plays an important role in the perception of WPV, it is due to greater experience and autonomy. It is for this reason that it is also expected that the greater the seniority in the organization, there will also be less perception of workplace violence.

2. Method

2.1 Sample and Procedures

This quantitative-based cross-sectional designs research was carried out between 2016 and 2018 in a total of 22 Spanish companies, SMEs, and large companies, distributed in 14 autonomous communities. For each company participating in the study, the questionnaire was distributed to the entire workforce. The only exclusion criteria were being on sick leave, having worked for the company for less than 3 months and understanding Spanish, since the validated version of the questionnaire was used in this language. The sample is made up of a total of 26741 people, of which 57.1% were women, distributed in the following sectors of activity: 32.8%, administration; 3.0%, waitresses; 25.7%, management; 22.4%, sellers; 14.3%, commercial cashiers; 1.9%, health personnel.

The sample was divided into six age groups: less than 20 years old (.4%); between 20 and 30 years old (7.9%); between 30 and 40 years old (27.4%); between 40 and 50 years old (49.5%); between 50 and 60 years old (14.5%); and over 60 years old (.4%). In five groups for seniority: less than 1 year (3.3%); between 1 and 2 years (6.0%); between 2 and 5 years (6.1%); between 5 and 10 years (35.3%); and more than 10 years (49.3%).

Before data collection, we contacted the heads of each company (e.g., Human Resources and Management) to explain the purpose and requirements of the study. Likewise, it was explained to all the people that the participation was voluntary, that the presentation of the data would be aggregated, and that any identifying information would be eliminated. The surveys were completely confidential, since the questionnaire did not ask for any personal information that could identify the author. Each person received access to the questionnaire in their email, through which they could access the online form. Data were collected over a one-month period.

2.2 Instruments

The variables were measured with previously validated scales and grouped into dimensions using the FPSICO 3.1 (Ferrer Puig et al., 2011), with a 3-point Likert-type response scale (no information, insufficient, adequate), 4 points (always, often, sometimes, never or almost never) or 5 points (always, often, sometimes, never, I don’t have/I don’t try).

From the FPSICO questionnaire, 9 risk factors are obtained: working time (α = .78), e. g., “Do you work Sundays and holidays?”; autonomy (=.87), e. g., “Can you make decisions regarding the distribution of tasks throughout your day?”; workload (α = .84), e. g., “How often should you pick up the pace of work?”; psychological demands (α = .78) e. g., “To what extent does your work require taking initiatives?”; variety and content (α = .69), e. g., “The work you do, do you find it routine?”; participation and supervision (α = .82), e. g., “What level of involvement do you have in the following aspects of your work. . . ”; worker’s interest/compensation (α = .86), e. g., “Does the company provide you with professional development (promotion, career plan,. . . )?”; role performance (α = .88), e. g., “You receive instructions that are contradictory to each other (some send you one thing and others another)”; social support relationships (α = .74), e. g., “How do you consider the relationships with the people you have to work with?”

To assess the perception of WPV, an additional dimension (α = .74) was employed, applying questions 18b, “how often do situations of physical violence occur at your job”; 18c, “situations of psychological violence (threats, insults, making emptiness, personal disqualifications. . . )”; 18d, “situations of sexual harassment” with a Likert-type response scale of 4 points (rarely, frequently, constantly, do not exist); and question 20, “in your work environment, do you feel discriminated? (by reason of age, sex, religion, race, education, category. . . )”, with a 4-point Likert-type response scale (always or almost always, often, sometimes, never). It has been considered to evaluate WPV with a 4-item construct, since it is more appropriate psychometrically to assess different forms of perception of mobbing than not using a single-item (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2016).

Nowadays, there are two approximations to measure the WPV, an objective measurement and a subjective measurement or also known as self-labelling that measures the perception to be victim of WPV (López & González-Trijueque, 2022). According to Niedl (1995), the subjective assessment originates a big interpersonal variability. However, in the present study, the method used bases on four items that measure the exhibition to specific behaviours of harassment of objective form. These items do not do reference to the bullying specifically to avoid victimization or sociocultural biases (Giorgi et al., 2011).

2.3 Analysis of Data

Internal consistency analyses (Cronbach’s alpha) and descriptive analyses (means, standard deviations, asymmetry, and kurtosis) of the variables considered in the study were performed using the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0.

To verify the hypotheses, mean comparison analyses were performed using ANOVA, to identify differences between age groups, seniority, and sex. Simple linear regression analyses were performed to try to explain the possible relationship between age and the perception of WPV and seniority and the perception of WPV.

3. Results

3.1 Internal Consistency

The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the scales used exceeded the cut-off point of .70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), except for the scales of WPV (α = .63) and variety and content (α = .69), being in both cases very close to this value.

The results of Harman’s single factor test Confirmatory Factor Analysis showed a poor fit of the single-factor test model for all psychosocial risk factors analyzed, including WPV: χ 2(35) = 32.310; SEM = .19; NFI<.001; IFI = < .001; T LI < .001; CFI < .001. To confirm these results, additional analyses were performed (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This approach means to add a firstorder factor to the investigator’s theoretical model with all measurements as indicators. Results showed that the model fit improved, even though none of the trajectory coefficients, corresponding to the relationships between the indicators and the general factor method, were significative. This finding suggested that, even though the method bias may be present, it does not significantly affect the results or the conclusions (Conger et al., 2000).

3.2 Hypothesis Test

3.2.1 Differences in perception of workplace violence between the sexes

The perception of WPV between both sexes through the ANOVA test is significantly higher in men (M = 6.31, SD = 7.82) than in women (M = 5.58, SD = 7.34) F(1,26739) = 60.79, p<.001 (see Figure 1).

According to the scale proposed by the FPSICO (Ferrer Puig et al., 2011) method to determine the risk levels of psychosocial factors, it is considered that there is a high risk with scores above the 75th percentile. From the results of perception of WPV (M = 5.90, SD = 7.56), it is concluded that 73% of the sample does not present risk (below the 75th percentile), compared to the remaining 27% with an elevated risk of being exposed to WPV. Based on this scale, it has been possible to calculate that the probability of suffering workplace harassment is 11% higher in men than in women (OR=1.11 95% CI 1.04-1.19).

Likewise, it can be seen that men have a significantly higher perception of physical violence F(1,26739) = 157.68, p < .001, psychological F(1,26739) = 90.28, p < .001 and sexual F(1,26739) = 22.32, p <.001. However, it is women who perceive significantly higher values in discrimination F(1,26739) = 38.35, p < .001 (see Figure 2).

3.2.2 Differences in perception of WPV between age groups

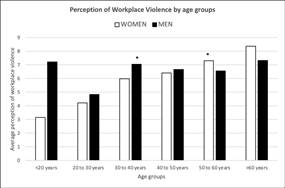

When analysed by age groups, we observe that the perception of WPV increases significantly with age, F(5,16247) = 17.87, p < .001. In the comparison between sexes and ages, we observe that the difference is significant in the groups between 30 and 40 years old, where the perception is greater in men than in women F(1,4447) = 19.91, p < .001, and without. However, in the group between 50 and 60 years old, this perception is reversed, being higher in women than in men F(1,2350) = 4.77, p = .029 (see Figure 3).

A linear regression analysis was performed to predict the perception of WPV based on age and sex, obtaining a significant regression equation F(1,16251) = 49.79, p < 0.001. The R2 value was .003, which indicates that 99.7% of the change in the perception of WPV can be explained by the regression model that includes age. The regression equation was 4.49+.52 (Age Group), in which the perception of WPV increases .52 points for every additional 10 years of age.

3.2.3 Differences in perception of WPV between seniority groups

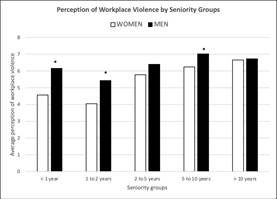

When analysed by seniority groups, we observe that the perception of WPV increases significantly with seniority in the organization, F(4,16169) = 17.98, p < .001. In the comparison between sexes and seniority, we observe that the difference is significant in the groups of <1 year (F(1,532) = 5.61, p = .018), in the group between 1 and 2 years old (F(1,962) = 9.34, p = .002), and in the group between 5 and 10 years old (F(4,5705) = 13.47, p =< .001), being the perception in men higher in the 3 cases (see Figure 4).

Note. (*) Analysis ANOVA with significant difference p < .05

Figure 4 Values of perception of workplace violence between sex by seniority groups

A linear regression analysis was performed to predict the perception of WPV based on seniority, obtaining a significant regression equation F(1,16251) = 52.69, p < 0.001. The R2 value was .003, which indicates that 99.7% of the change in the perception of WPV can be explained by the regression model that includes age. The regression formula was 4.61+.44*(Antiquity Group), in which the perception of WPV increases .44 points for each additional rank of seniority.

3.2.4 Differences in the perception of WPV according to the level of psychosocial risks

The nine psychosocial risk factors obtained with the FPSICO (Ferrer Puig et al., 2011) method were added, and a linear regression analysis was performed between total psychosocial risks and the perception of WPV (dependent variable), obtaining a significant regression equa tion F (1,26738) = 7653.63, p < .001. The value of R2 was .223, which indicates that 77.7% of the change in the perception of WPV can be explained by the regression model that includes psychosocial risks. The regression equation was 5.96+.03*(Psychosocial Risk), in which the perception of WPV increases .03 points as the total sum of psychosocial risk factors increases.

A correlation analysis was performed between WPV and psychosocial risk factors (see Table 1), observing a significant correlation with all of them. The risk factors with the greatest impact on WPV are role performance, social support relationships, and variety and content (routine). These results agree with those obtained by other authors, who associated WPV with the lack of interpersonal communication (Bentley et al., 2014), with role conflict, interpersonal relationships, and job demands (Zahlquist et al., 2019).

4. Discussion

Regarding the impact of psychosocial risks on workplace violence (WPV), it is observed that there is a significant linear relationship between the two, thus accepting hypothesis H 1. It is confirmed that WPV manifests itself more easily in environments subject to stress, with poor communication, lack of recognition (Hirigoyen, 2001) and where there are interpersonal conflicts (FigueiredoFerraz et al., 2012).

According to the results obtained, we can reject the first hypothesis H 2 raised in the study, since it is observed that it is the group of men who has significantly higher values in perception of WPV compared to women. In fact, men are 11% more likely to perceive WPV than women. It should be noted that this result is consistent with the results obtained in a cross-sectional study carried out in Canada, where more men declared being victims of WPV than women. According to this study, income level is negatively associated with reporting violence. One possible explanation is that people with lower salaries may be afraid to declare violent acts for fear of being fired (Azaroff et al., 2002). It has also been observed that for men, the fact of having been a victim of WPV predisposes them to make complaints of violence in the future, although this result has not been observed in women (Sato et al., 2013). In relation to the WPV received by clients, it has also been reported to be higher in men than in women, because male workers are more likely to wield aggression against clients and therefore to draw aggression and violence toward themselves (Enosh & Tzafrir, 2015). Breaking down WPV into physical, psychological, sexual violence, and discrimination, we observed the same trend except for discrimination, which turned out to be significantly higher in women. This finding agrees with the results obtained by other authors, who report that discrimination against women goes beyond the workplace, extending to their personal sphere. Surely, this is the reason why women have higher perceptions of discrimination than men (van de Griend & Messias, 2014).

In the analysis by age groups, we observe that the perception of WPV increases significantly with age and not the other way around, as proposed in hypothesis H 3. Therefore, this second hypothesis is also rejected. It must be considered that this study is only assessing the perception of violence and not coping strategies, which according to previous studies turns out to be higher in middle-aged groups (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2004), as well as a greater resistance of older people against negative effects of harassment (Lim, 1996). However, it could be related to the greater job security requirements of older people, due to family and financial burdens (Finegold et al., 2002; Kuhnert & Vance, 2004), in such a way that this greater perception of WPV with increasing age could be more related to the emotional impact than to a greater frequency of WPV.

In the analysis by seniority groups, we observe the same trend as by age, in such a way that with greater seniority in the organization, there is a significantly greater perception of WPV, thus rejecting the third hypothesis H 4. It seems that seniority plays an important role in managing conflicts with patients (Dopelt et al., 2022). However, the sample analysed in this study has a minority of healthcare workers, so this trend cannot be appreciated. In this case, it seems that the seniority results are equated with the age results, where the greater the age, and therefore the greater the seniority, the perception of WPV is more intense.

5. Limitations and Future Studies

Regarding the instruments used, although they are selfreported tests (with the possible bias that these may entail), those whose validity and reliability are widely documented were chosen.

For the evaluation of workplace violence, a 4-item scale extracted from a psychosocial risk survey has been used. Although the reliability of the scale used is good (α = .74), and it is known that it is a good option to use scales with four items as opposed to one with only one (Garthus-Niegel et al., 2016), the method employed has not yet been validated as other methods of recognized prestige (e. g., Gutenberg scale). For this reason, it is considered highly relevant to carry out a psychrometric validation of this 4-item scale used.

Table 1 Pearson’s correlation between psychosocial risk factors and perception of workplace violence

| Correlations | WV | WT | AU | WL | PD | VC | PS | WIC | RP | SSR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace violence | Pearson’s correlation | 1 | .052** | .295** | .268** | .275** | .313** | .327** | .275** | .404** | .395** | |

| Sig. (Bilateral) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||

| | | N | 26.741 | 26.741 | 26.741 | 26.741 | 26.740 | 26.741 | 26.741 | 26.741 | 26.741 | 26.741 | |

Note. **. The correlation is significant at the .01 level (bilateral). WV: Workplace Violence; WT: Work Time; AU: Autonomy; WL: Workload; PD: Psychological Demands; VC: Variety and Content; PS: Participation and Supervision; WIC: Worker’s Interest/Compensation; RP: Role Performance; SSR: Social Support Relationships (without workplace violence questions).

An additional limitation is based on the existence of some underrepresented demographic groups within the sample, such as the groups <20 and >60 years of age. It is very possible that the lack of significant differences in these two groups is due to the small sample size, and therefore this limitation must be considered.

Finally, for future research it would be interesting to study the effect of organizational interventions aimed at reducing WPV, and to see if they also have a different effect depending on sex and different age groups.

It would also be interesting to be able to delve deeper into the risk factors that impact WPV, which will also allow us to develop intervention programs aimed at reducing or eliminating WPV.

6. Conclusion

Workplace violence (WPV) is one of the most worrying risk factors in organizations, given its relevance and negative impact, with a great impact on job satisfaction, engagement, and performance. Studies show that people who experience WPV have significantly higher levels of job stress, physical and psychological problems, and leave the workplace more frequently (Chan et al., 2008).

For this reason, it is important to know the relationship between the perception of WPV and demographic variables such as age, sex, and seniority in the company, or if there is any relationship with psychosocial risks.

The results show that there is a direct relationship between psychosocial risks and the perception of WPV. Thus, coinciding with other authors (Bentley et al., 2014; Figueiredo-Ferraz et al., 2012; Hirigoyen, 2001; Song, 2021; Zahlquist et al., 2019).

it is shown that WPV appears more frequently in environments subject to stress, poor interpersonal relationships, lack of role clarity or toxic leadership styles.

Previous studies show that women are more likely to suffer WPV than men (Waite, 2021). In the other hand, in the present study an inverse relationship is observed, positioning the group of men with significantly higher values in perception of WPV than women. Men obtained higher values in perception of physical, mental, and sexual violence. Nevertheless, discrimination remains significantly higher in women.

Coping with threats of harassment according to age seems to be related to coping with stress. Some authors show that older people have a better capacity to regulate the negative effects of stress (Carstensen, 1995), and can apply proactive coping strategies, which gives them greater resistance to the negative effects of WPV (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2004). However, it is also observed that older people may perceive workplace bullying as a greater threat than young people, given that they have greater responsibilities and family burdens (Lundberg-Love & Marmion, 2003). This study shows that the perception of workplace bullying increases significantly with age and seniority in the company. It is possible that it is related to the fear of job loss that these threats entail, or that greater seniority implies greater permanence in the organization and therefore more interpersonal relationships that can cause WPV.

7. Practical Implication

The results obtained show us that the perceptions of WPV can be different, depending on their sex, age, and seniority. This implies that not all groups should be treated in the same way and that psychosocial interventions should be personalized. We can also base the psychosocial intervention on reducing the risk factors present in the organization, especially on improving the work environment, reducing role conflict and routine, which are the factors that have been shown to have the greatest impact on WPV.