1. Introduction

Developing a comprehensive picture of “sexual attitudes” implies a hard effort. In a review of current literature (Velo & Ruiz, 2023), we found two main difficulties: the first one is the unlike current definition of what an at titude is, reporting distinctly depending on different as pects such as the value of the action (Redfearm & Laner, 2000), a moral judgment (Blanc et al., 2018), a mix of social norms, own beliefs, and own behavioural tenden cies (Marks & Fraley, 2005), or a general overview of one’s own personal perspective when evaluating situa tions (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014), among others.

In fact, other variables such as desires regarding sexual and romantic relationships (Maxwell et al., 2017), or even the concept of “sexual beliefs” (Nobre & Pinto-Gouveia, 2006) have also been labelled with the term “attitude”. Furthermore, in our previous review, we revealed variables that have different names but almost identical descriptions (Velo & Ruiz, 2023). For instance, Erotophilia (del Río et al., 2013) and Eroticism (Brito-Rhor et al., 2020).

This inconsistent conceptualization of sexual attitud es is not new. For example, in the questionnaire assess ment review by Blanc and Rojas (2017), the authors discussed how “production is diverse and dispersed” (p. 18), either at a conceptual level or in the way of measure ment, and concluded that there is a need for a “precise definition acknowledged by specialists” (p. 23).

Albeit this inconsistency related to the definition of sexual attitudes, a second main difficulty was identified in the high variability within the structures of previous proposals. In our work (Velo & Ruiz, 2023), we set a theoretical criterion to define what a self-oriented cogni tive schema of sexual behaviour (SO-CSSB) is, in order to review studies that fit that frame. The key point was that even though the scope of the included variables was shared, the reports which were found did not follow a common structure of considerations or a shared model. Table 1, extracted from that review (Velo & Ruiz, 2023), illustrates how several studies to date have not broached sexual attitudes in a unified way, matching again with the aforementioned “diverse and dispersed” discussion of Blanc and Rojas (2017).

As we already discussed, we could not find a broad model which encompassed the wide range of variables. On the contrary, we reported a set of different defini tions and conceptual structures that had been shortly described, and which were not based on any kind of val idated model of cognition on sexual behaviour. More over, we are not the first authors to offer these conclu sions. Despite the large volume of research focused on sexual attitudes, several authors have discussed the lack of unified evidence that leads to variability of perspec tives, fuzzy labelling, and, also, inconsistency among the studies (Blanc & Rojas, 2017; Kane et al., 2019; Sánchez-Fuentes & Santos-Iglesias, 2016; Shaw & Rogge, 2016).

With this background it is not possible to properly assess attitudes towards sexual behaviour simply based on raw definitions extracted from the literature, but rather a disambiguation process is needed. Therefore, our work had to be divided into a two-step research pro cess. For the first part, we attempted to use information strictly stemmed from the thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to consolidate a theoretical unification ex tracted from the current literature, by gathering and analysing prior definitions, and bearing in mind the self oriented meaning and the likely interference of moral judgment in the description of the items (Velo & Ruiz, 2023). This first step sought to overcome the “insuffi cient reporting of qualitative research methods used to generate questionnaires” (Ricci et al., 2019 p. 153),, ensuring rigor in the literature disambiguation as the subsequent baseline for developing the model.

From that effort, the systematic review of the liter ature added to the thematic analysis of the variables re sulted in a compilation of 17 self-oriented cognitive schema ta of sexual behaviour (SO-CSSB). This outcome gath ered definitions used in previous studies and relabelled them using a common classification which aimed to achieve the maximum possible scope. Those theoretically de fined factors included several areas of appraisal and self oriented beliefs such as general perception, the search of pleasure or pain (self or partner oriented), spirituality, role performance, self-presentation, emotional bond, re production, behavioural variability in different scenarios, the achievement of non-sexual profits, and the importance of own and partner’s faithfulness (Velo & Ruiz, 2023).

Nevertheless, this review does not provide a model vali dation process from real-world data, but only a theoretical compilation and disambiguation of the literature. There fore, it is still not possible to assure the proposal’s level of adjustment. This is why a second step is needed to collect real-world data from a sample of subjects, and to explore the composition structure and adequacy of the model in a comprehensive exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

For that purpose, it becomes imperative to rely on the subjects’ individual self-reports, assuming that sex ual behaviour attitudes cannot be observed directly. Re gardless of the differences in cultural norms around the world, sexual behaviours and related information are commonly constrained to private activity, censored, or, at least, subject to some kind of cultural pressure (Fen ton et al., 2001; Langhaug et al., 2010).

In this regard, three characteristics of the assessment may influence the reliability of self-reports (Durant & Carey, 2000; Langhaug et al., 2010): one is the pri vacy of the information held; other key is the perceived anonymity; and, additionally, the credibility of the re search team or assessor.

Self-reports have been concluded to provide more ac curate results and less discrepant responses than face-to-face interviews (FTFI) in different populations (Durant & Carey, 2000; Langhaug et al., 2010). For that rea son, the self-administered questionnaires (SAQ) may be the most used method for studies on sexual behaviour (Durant & Carey, 2000).

Table 1 Extracted from (Velo & Ruiz, 2023): “Table 3. Grid of Information Gathered and Sources”

| Erotophilia | Erotophobia | Self-pleasure | Partner’s pleasure | Spirituality | Domination | Submissiveness | Cooperation | Self-pain | Partner’s pain | Self-presentation | Variability | Emotional attachment | Instrumentality | Reproduction | Resolution (unfaithfulness) | Susceptibility (unfaithfulness) | ||||

| Questionnaire’s authors | Year | Sum | Questionnaires* | |||||||||||||||||

| Arcos-Romero et al. | 2020 | • | 1 | SOS-6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Barrada et al. | 2018 | • | • | 2 | SOI | |||||||||||||||

| Brito-Rhor et al. | 2019 | • | • | • | • | 4 | IEASF | |||||||||||||

| del Río et al. | 2013 | • | • | • | • | 4 | EROS | |||||||||||||

| Fino et al. | 2018 | • | • | • | • | 4 | TSAQ | |||||||||||||

| Hendrick et al. | 2006 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 8 | BSAS | |||||||||

| Horn et al. | 2015 | • | 1 | ESS | ||||||||||||||||

| Leiblum et al. | 2003 | • | • | • | • | 4 | CCAS | |||||||||||||

| Lief et al. | 1990 | • | • | 2 | SKAT-A | |||||||||||||||

| Nobre et al. | 2003 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 9 | SDBQ | ||||||||

| Meskó et al. | 2022 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 12 | YSEX?-HSF | |||||

| Shaw and Rogge | 2016 | • | • | • | • | 4 | QSI | |||||||||||||

| Snell et al. | 1993 | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | MSQ | ||||||||||||

| Stulhofer et al. | 2010 | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | NSSS | ||||||||||||

| Tavares et al. | 2021 | • | 1 | MSP/PSP | ||||||||||||||||

| Reviews | Year | |||||||||||||||||||

| Buhi and Gooson | 2007 | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Calvillo et al. | 2018 | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Carpenter | 2001 | • | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| DeNeef et al. | 2019 | • | • | 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Impett and Peplau | 2003 | • | • | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Kane et al. | 2019 | • | • | • | • | • | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Marston anKing | 2006 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 6 | |||||||||||

| McKee et al. | 2021 | • | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Petersen and Hyde | 2011 | • | • | • | • | • | 6 | |||||||||||||

| Sánchez-Fuentes et al. | 2014 | • | • | • | • | • | • | 6 | ||||||||||||

| Wesche et al. | 2021 | • | • | • | • | • | • | 6 | ||||||||||||

| Woertman and van den Brink | 2012 | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Yapp and Quayle | 2018 | • | • | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| % of records included in the review | 53 | 39 | 57 | 21 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 46 | 21 | 60 | 14 | 10 | 21 | 14 |

Note. SOS-6 (Sexual Opinion Survey); SOI (Sociosexual Orientation Inventory); IEASF (Instrumento de Evaluación del Autoesquema Sexual Femenino); EROS (Encuesta Revisada de Opinión Sexual); TSAQ (The Trueblood Sexual Attitudes Questionnaire); BSAS (Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale); ESS (Embodied Spirituality Scale); GCAS (Cross Cultural Attitude Scale); SKAT-A (Sexual Knowledge and Attitude Test for Adolescents); SDBQ (Sexual Dysfunctional Beliefs Questionnaire); YSEX7-HSF (Why Hungarians Have Sex? Developed in Hungarian sample); QSI (Quality of Sex Inventory); MSQ (Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire); NSSS (New Sexual Satisfaction Scale); MSP/PSP (Maternal Sex during Pregnancy/Partner Sex during Pregnancy).

The SAQ allows participants to be less influenced by social desirability to answer every question, although it is reported to increase answer rates compared to other self-report surveys in different populations (Durant & Carey, 2000; Langhaug et al., 2010).

In addition to affording privacy, they are less labour intensive to researchers, and make it possible to adminis ter them to a larger number of subjects in an affordable way (Blumenberg & Barros, 2018; Fenton et al., 2001; Langhaug et al., 2010).

In conclusion, SAQs are reported as a preferred method to reduce the cost of distribution and administration (Blumenberg & Barros, 2018; Fenton et al., 2001; Langhaug et al., 2010), and yield the most accurate infor mation (Durant & Carey, 2000; Langhaug et al., 2010; Schroder et al., 2003).

For all those reasons, the SO-CSSB theoretical model stands as a substantiated candidate to draw a comprehen sive framework for attitudes towards sexual behaviour, and may be evaluated through self-reported methods.

Thereby, the aim of the present study was to empir ically explore the structure of the SO-CSSB model. It was planned in two operational objectives: 1) to develop a prototype of a questionnaire substantiated on the the oretical review and 2) to explore the structure of the SO-CSSB model.

2. Method

The present study was designed in two stages, starting with the development of a questionnaire from the theo retical proposal, and followed by the data analysis for structure exploration. The study was evaluated and ap proved by the ethics committees of the Doce de Octubre, Gregorio Marañón and Clínico San Carlos hospitals, and that of the Autonomous University of Madrid.

2.1 Item Generation and Expert Panel

A prototype questionnaire was designed based on the theoretical approach (Velo & Ruiz, 2023). It included 4 items for each SO-CSSB factor, distributed in a non- consecutive order. Items were created to describe ob jectives, drives, motivations, attitudes, as well as the degree of satisfaction/annoyance in the fulfilment of the factor, following SO-CSSB criteria. Thereby, the 4 items of each factor were designed to express levels of intensity in a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, referring to one’s own perception at present from minimum self-identification to maximum, respectively.

The questionnaire was presented to an expert panel that consisted of four psychologists specialized in dif ferent areas of sexual behaviour, who made comments they considered relevant to improve the instrument, and rated every feature: theoretical factors adequacy, item descriptions linked to the factors’ meaning, adequacy of the Likert type of items for the purpose of the study, item understanding, questionnaire accessibility and for mat adjustment to different devices, and questionnaire length from 0 (minimum) to 5 (maximum).

2.2 Pilot Administration

The proposed instrument was administered to 10 sub jects who were asked for feedback regarding any possible difficulty that could be encountered while answering it. The comments alluded to three areas: excessive length of the questionnaire, overlapping, and difficulty under standing some items.

Once all the information was collected, the question naire was modified to adapt it to the comments from the expert panel and pilot subjects, in order to make it eas ier to understand and answer. Finally, sets of items for every theoretical factor were reduced from four to three, except for Resolution and Susceptibility to unfaithful ness, due to content considerations.

2.3 Quantitative Analysis

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted. It was approved by the ethical committees of Doce de Oc tubre, Gregorio Marañón and Clínico San Carlos hospi tals, and the one of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

2.3.1 Sample

Subjects were selected by incidental sampling amid the participants and patients of the hospitals involved in the project, from external centres, in different outreach ac tivities organized by the research group, and using the snowball method from already recruited subjects. All participants signed the informed consent, were Spanish speakers and at least 18 years old, had to be able to receive emails, and were not diagnosed with any impair ment which could prevent them from understanding and answering the questionnaire.

2.4 Procedure

The newly designed questionnaire was administered on line once the informed consent had been accepted and signed. The instrument was sent to the subjects’ email address. They were asked to answer all the questions in one attempt, considering only their current situation. Finally, they were also offered to comment on the un derstanding or composition of the questionnaire. No comments were received.

No participant was paid or rewarded in any way for participating.

All items were coded and scored with Qualtrics on line survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, Copyright ©2020). The completion rate was over 80% for the 16 incom plete questionnaires, which were imputed using R software (R core team, 2020) with random forest multiple imputation. The outcome of the analysis was compared with non-imputed results.

Table 2 Sample Description

| Variable | Descriptive |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean 25.27 | |

| SD 6.61 (18-56) | |

| Biological sex | |

| Male | 62 (33.2%) |

| Female | 125 (66.8%) |

| Gender (self-identified, mostly fitted) | |

| Masculine man | 63 (33.5%) |

| Feminine man | 2 (1.1%) |

| Masculine woman | 5 (2.7%) |

| Feminine woman | 113 (60.1%) |

| Trans woman (man born) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Agender (neutro) | 4 (2.1%) |

| Academic level | |

| Basic | 5 (2.7%) |

| Medium Professional degree of Bachelor | 58 (30.9%) |

| High Professional degree or University degree | 60 (31.9%) |

| University postgraduate | 65 (34.6%) |

| Household income per year | |

| <20k | 84 (44.7%) |

| 20-25k | 43 (22.9%) |

| 25-30k | 30 (16%) |

| >30k | 30 (16%) |

Table 3 Total Variance Explained

| Component | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadingsa | ||

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | |

| 1 | 5.554 | 10.480 | 10.480 | 4.270 |

| 2 | 4.706 | 8.879 | 19.358 | 3.196 |

| 3 | 3.339 | 6.299 | 25.658 | 3.028 |

| 4 | 3.169 | 5.980 | 31.637 | 2.688 |

| 5 | 2.492 | 4.701 | 36.339 | 3.278 |

| 6 | 2.246 | 4.237 | 40.576 | 2.630 |

| 7 | 1.814 | 3.422 | 43.998 | 3.036 |

| 8 | 1.748 | 3.299 | 47.296 | 2.103 |

| 9 | 1.576 | 2.973 | 50.269 | 1.677 |

| 10 | 1.541 | 2.908 | 53.177 | 2.565 |

| 11 | 1.420 | 2.679 | 55.856 | 2.255 |

| 12 | 1.351 | 2.549 | 58.405 | 1.730 |

| 13 | 1.323 | 2.496 | 60.901 | 1.674 |

| 14 | 1.154 | 2.177 | 63.079 | 1.591 |

| 15 | 1.117 | 2.108 | 65.186 | 2.393 |

| 16 | 1.076 | 2.031 | 67.217 | 2.260 |

Table 4 EFA Structure Matrix

| Component | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 48 | .854 | |||||||||||||||

| 50 | .854 | |||||||||||||||

| 53 | .797 | |||||||||||||||

| 52 | .780 | |||||||||||||||

| 47 | .563 | -.558 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16 | .734 | |||||||||||||||

| 27 | .687 | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | .678 | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | .581 | |||||||||||||||

| 30 | .522 | |||||||||||||||

| 24 | .858 | |||||||||||||||

| 18 | .727 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | .646 | -.538 | ||||||||||||||

| 22 | .862 | |||||||||||||||

| 28 | .833 | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | .535 | .495 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | .852 | |||||||||||||||

| 42 | .792 | |||||||||||||||

| 31 | .781 | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | .725 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | .811 | |||||||||||||||

| 20 | .805 | |||||||||||||||

| 32 | .776 | |||||||||||||||

| 44 | -.783 | |||||||||||||||

| 11 | -.687 | |||||||||||||||

| 37 | -.674 | |||||||||||||||

| 25 | ||||||||||||||||

| 23 | -.80 | |||||||||||||||

| 36 | -.745 | |||||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | .663 | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | .614 | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | .753 | |||||||||||||||

| 45 | .745 | |||||||||||||||

| 40 | .718 | |||||||||||||||

| 49 | .755 | |||||||||||||||

| 51 | .570 | -.640 | ||||||||||||||

| 39 | .796 | |||||||||||||||

| 46 | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| 38 | -.658 | |||||||||||||||

| 26 | -.59 | |||||||||||||||

| 35 | ||||||||||||||||

| 29 | .724 | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | .491 | |||||||||||||||

| 43 | ||||||||||||||||

| 33 | .778 | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | .763 | |||||||||||||||

| 21 | .548 | |||||||||||||||

| 41 | .692 | |||||||||||||||

| 34 | .608 | |||||||||||||||

| 15 | .557 | |||||||||||||||

2.5 Analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted (Principal Axis extraction method with oblique rota tion). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was performed to evaluate worthiness of the correlation matrix (null hy pothesis indicates that the variables are uncorrelated), and also KaiserMeyerOlkin test (KMO) was reported to evaluate the adequacy of the analysis technique. Follow ing the Kaiser and Guttman K1 rule, only factors with eigenvalues greater than one were selected.

Reliability analysis was performed using Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega indexes. Both indica tors were considered because of the Likert-type variables (Hayes & Coutts, 2020) and multidimensional structure. For the sets with only two items, the Spearman-Brown coefficient was used (Eisinga et al., 2013).

3. Results

The results of the expert panel survey regarding the qual ity of the questionnaire were the following: theoretical factors adequacy (M = 5, SD = 0), item description linked to factors’ meaning (M = 4.75, SD = .5), adequacy of the Likert type of items for the purpose of the study (M = 4.75, SD = .5), item understanding (M = 4, SD = .81), questionnaire accessibility and format adjustment to different devices (M = 4.5, SD = 1), and questionnaire length (M = 4, SD = .81). One comment was received expressing the excessive length of the instrument.

From all the participating centres, 345 subjects were recruited. Of them, 207 answered all the characteriza tion questions and 188 completed over 80% of the ques tionnaire (172 complete).

Mean age was 25.27 (SD: 6.61) from 18 to 56, and 66.8% of subjects were biological females. In addition to that, 93.5% of biological males identified themselves with the masculine male gender, while 88.8% of the bi ological females identified themselves with the feminine female gender.

The first step was a comparison of the results from the exploratory factor analysis before and after includ ing the imputed answers. No relevant differences were found in item classification or model outcome (n = 172: KMO = .661, Barlett’s = 3789.1, sig.<.01, 70.1% of the variance explained; vs. n = 188: KMO = .672, Barlett’s = 3958.7, sig.<.01, 67.2% of the variance explained). Fi nally, the imputation of 16 subjects was performed and included in the analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis of the 53 items yielded 16 factors with eigenvalues above 1, accounting for 67.21% of the available variance (see Table 3), and item com- munalities ranging from .44 to .80. Table 4 shows the structure matrix with the items of each component, with an agreed-upon cut off of >.49 (Kyriazos, 2018), which resulted in loadings from .49 to .86.

Finally, the internal consistency of each factor was assessed computing Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonal’s Omega’s indexes. For the sets with less than three items, reliability was assessed using Spearman-Brown coeffi cient (Eisinga et al., 2013), as it can be seen in Table 5. Every component was reassessed to evaluate the suitable labelling in terms of the EFA outcome. Additionally, Ta ble 6 shows that no correlation between components over .20 was found, ranging from -.19 to .20.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to add a quantitative framework to a previously reported disambiguation re view and theoretical proposal of cognitive schemata on sexual behaviour (Velo & Ruiz, 2023), in order to em pirically identify its factors and evaluate the feasibility of the model for further research. As shown in Table 5, we found a preliminary set of results supporting the general meanings of the suggested factors but with some key changes needed.

First, the factors related to faithfulness were consis tent with the initial proposal (Velo & Ruiz, 2023). The only discrepancy was an initial item planned for Resolu tion that was finally included as a Susceptibility factor (see result 1, Table 5), even though one component focused on Resolution came up too (see result 11, Table 5).

We considered this outcome to be a relevant find be cause of the need to distinguish between two options for unfaithfulness: if the concept applies equally no matter whether it relates to infidelity intercourse or experienc ing jealousy, or, on the contrary, as upheld by Schmitt and Buss (2000), they are different factors with different attributes for individuals.

Thus, in the light of our results, we considered it suitable to assess them separately for a correct evalua tion of the schemata, but taking into account a likely connection between them.

On the contrary, a different outcome was found re garding the theoretical factors related to seeking pleasure (Partner’s and Self-oriented). The EFA yielded one factor containing items from Partner’s pleasure, Self-pleasure, Self-presentation, and the inversed form of a strict item of Reproduction, which leave out the pleasure motiva tion in sexual activity. Thereby, we addressed this result as evidence of a probable general pleasure-orientation in the context of intercourse, self- and partner-oriented, in which sexual joy or delight is the main purpose of the action (Pleasure focus; see result 2, Table 5).

Moreover, this Pleasure Focus was not the only pleas ure-oriented outcome. Another yielded component was found, including 2 items of self-pleasure (see result 8, Ta ble 5), which likely evidences a specific identification of a self-oriented need of physical pleasure to achieve a satisfying experience (Self-pleasure).

Table 5 Summary of EFA and Reliability Analysis

| Exploratory factor analysis | Scale analysis and decision making | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Total | % of variance loading | Items resulted* Factors theoretically based | Reliability*** | Final label |

| 1 | 5.554 | 10.48% | 4 Susceptibility to unfaithfulness (1 inversed load) | α = .860 | Susceptibility to unfaithfulness |

| 1 Resolution to unfaithfulness (inversed load) | |||||

| 2 | 4.706 | 8.87% | 2 Partner’s pleasure | α = .67 | Pleasure focus |

| 1 Self-presentation | |||||

| 1 Self-pleasure | |||||

| 1 Reproduction (inversed load) | |||||

| 3 | 3.339 | 6.29% | 2 Partner’s pain | α = .75 | Pain focus |

| 1 Self- pain | |||||

| 4 | 3.169 | 5.97% | 1 Erotophilia | α = .72 | Social erotoph |

| 2 Erotophobia (both inversed load) | |||||

| 5 | 2.492 | 4.70% | 2 Submissiveness | α = .81 | Submissiveness |

| 2 Self-pain | |||||

| 6 | 2.246 | 4.23% | 3 Spirituality | α = .77 | Spirituality |

| 7 | 1.814 | 3.42% | 2 Domination | α = .66 | Domination |

| 1 Partner’s pain | |||||

| 8 | 1.748 | 3.29% | 2 Self-pleasure | r = .63 | Self-pleasure |

| 9 | 1.576 | 2.97% | 1 Cooperation | r = .47 | Agreement |

| 1 Submissiveness | |||||

| 10 | 1.541 | 2.90% | 3 Instrumentality (1 inversed load) | α = .66 | Instrumentality |

| 11 | 1.420 | 2.67% | 2 Resolution to unfaithfulness (inversed load) | r = .68 | Resolution to unfaithfulness |

| 12 | 1.351 | 2.54% | 1 Self-presentation | Self-presentation | |

| 13 | 1.323 | 2.49% | 2 Cooperation | r = .46 | Desist |

| 14 | 1.154 | 2.17% | 1 Reproduction (inversed load) | r = .61 | Variability |

| 1 Variability | |||||

| 15 | 1.117 | 2.10% | 3 Emotional attachment | α = .67 | Emotional attachment |

| 16 | 1.076 | 2.03% | 2 Erotophilia | α = .64 | Erotoph/ |

Note. *Number of items resulted for each factor out of the 3 designed for each aspect, 4 in the case of Resolution and Susceptibility to unfaithfulness. They are labelled by every theoretical area they are meant to, as defined in the disambiguation review (Velo & Ruiz, 2023). **Only items with factor load >.50 are shown in the table. ***α=Cronbach’s alpha; r=Spearman-Brow coefficient. McDonald’s omega is not shown because no differences over .03 with Cronbach’s alpha were found.

Table 6 Component Correlation Matrix

| Comp. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 1 | 1.000 | -.009 | −.126 | .156 | −.068 | .057 | −.026 | .003 | −.060 | −.094 | −.166 | −.030 | .064 | −.062 | .142 | −.101 |

| 2 | -.009 | 1.000 | −.035 | .033 | .059 | .109 | −.190 | −.100 | .005 | −.003 | −.046 | .135 | −.085 | −.029 | .023 | .086 |

| 3 | -.126 | -.035 | 1.000 | .008 | .128 | −.006 | −.096 | −.038 | .054 | .201 | .072 | .006 | .007 | .073 | −.091 | −.062 |

| 4 | .156 | .033 | .008 | 1.000 | .031 | −.023 | −.163 | −.066 | .037 | −.015 | .029 | −.004 | .050 | −.020 | −.039 | .161 |

| 5 | -.068 | .059 | .128 | .031 | 1.000 | .045 | −.120 | .045 | .026 | .078 | .058 | .039 | −.050 | −.027 | −.054 | .078 |

| 6 | .057 | .109 | −.006 | −.023 | .045 | 1.000 | −.083 | .026 | −.024 | −.025 | .008 | .104 | .016 | .064 | .141 | −.031 |

| 7 | -.026 | -.190 | −.096 | −.163 | −.120 | −.083 | 1.000 | .016 | −.047 | −.063 | −.021 | −.108 | .040 | −.048 | −.048 | .008 |

| 8 | .003 | -.100 | −.038 | −.066 | .045 | .026 | .016 | 1.000 | .000 | −.035 | .025 | −.051 | .050 | .049 | −.061 | −.029 |

| 9 | -.060 | .005 | .054 | .037 | .026 | −.024 | −.047 | .000 | 1.000 | .074 | .016 | .028 | −.004 | −.034 | −.040 | .040 |

| 10 | -.094 | -.003 | .201 | −.015 | .078 | −.025 | −.063 | −.035 | .074 | 1.000 | .013 | .014 | .023 | .093 | −.011 | −.066 |

| 11 | -.166 | -.046 | .072 | .029 | .058 | .008 | −.021 | .025 | .016 | .013 | 1.000 | −.029 | −.009 | .081 | −.160 | .007 |

| 12 | -.030 | .135 | .006 | −.004 | .039 | .104 | −.108 | −.051 | .028 | .014 | −.029 | 1.000 | −.022 | .067 | .014 | −.028 |

| 13 | .064 | -.085 | .007 | .050 | −.050 | .016 | .040 | .050 | −.004 | .023 | −.009 | −.022 | 1.000 | .028 | −.029 | −.003 |

| 14 | -.062 | -.029 | .073 | −.020 | −.027 | .064 | −.048 | .049 | −.034 | .093 | .081 | .067 | .028 | 1.000 | −.032 | −.074 |

| 15 | .142 | .023 | −.091 | −.039 | −.054 | .141 | −.048 | −.061 | −.040 | −.011 | −.160 | .014 | −.029 | −.032 | 1.000 | −.049 |

| 16 | -.101 | .086 | −.062 | .161 | .078 | −.031 | .008 | −.029 | .040 | −.066 | .007 | −.028 | −.003 | −.074 | −.049 | 1.000 |

We consider this result highlights the main idea up held throughout the theoretical and empirical study: sche mata may vary and differentiate depending on the self or outer focus of the action. One’s own consideration within a given scenario constitutes then a key variable to have in mind when evaluating sexual behaviour and appraisal. In this case, equal pleasure is found to be a general objective for individuals themselves and when they focus on their partners, but another specific consid eration turns up remarking the own and personal phys ical intercourse experience.

Furthermore, we found more changes in factors re lated to social standing and pain. Although we theo retically divided them into role (Domination and Sub missiveness), and pain focus (Partner’s and Self), they finally turned out to be just three factors with mixed items from the previous four.

We reviewed the item descriptions in order to un derstand the reorganization and considered that those pain items eventually associated with role performance were the ones depicted with the lowest level of intensity. Therefore, we discussed the possibility of distinguishing between these two apparently related aspects. For one thing, what subjects understood as a role performance (eventually defined by items theoretically designed for Domination + Partner’s pain, and Submissiveness+Self- pain), as shown in results 5 and 7 in Table 5, would not mean hard pain or humiliation but may only imply a graded way of interacting during intercourse. This role would differ from what we called Pain Focus (see result 3, Table 5), which consequently means a tendency specif ically oriented to higher intensity of physical or mental suffering, aimed at oneself or one’s partner.

This reassignment and the careful analysis of the items led us to discuss the Domination and Submis siveness roles as possibly being associated to some be haviours and attitudes with mild or moderate intensity, unlikely perceived by subjects who consider the sexual context as a scenario of intense pain-oriented acts (Pain focus), in which the intensity of similar actions may de fine the way individuals plan, behave and appraise.

Another change showed by the analysis was the general conceptualization of sexual intercourse (Erotophilia and Erotophobia), which were intentionally proposed using two terms, although they had also been previously defined as two poles of the same factor (Shaw & Rogge, 2016).

Indeed, we finally labelled the continuum between those two poles, philia and phobia, Eroto/ (see 16, Table 5). Unexpectedly, we found that individuals selected the newly designed items by answering in different patterns for what could be labelled as Social erotoph/ (see result 4, Table 5), and the relevant result, (self) Erotoph/ (see 16, Table 5).

This conclusion of splitting Erotoph/ into social and self was made after a careful review of the items that com pose both factors and becoming aware of the unlikely def inition of those focused on self or outer purpose. While trying to formulate items following the SO-CSSB condi tions (Velo & Ruiz, 2023), it seems that we crossed the line between one’s own and others’ appraisal, and eventu ally participants pointed it out. These results strengthen again the main precept of the need of individual and self-focused assessment in sexual behaviour to avoid biases in the final outcomes. We, therefore, decided to remove Social Erotoph from our final model given that it did not meet the baseline conditions and, consequently, we labelled Self-erotoph/ as simply Erotoph/.

The EFA also pointed out that Cooperation was an other factor subject to modification. It was divided into another two components, which we discussed from their item composition as one oriented to the degree of explicit agreement among partners during sexual in tercourse (Agreement; see result 9, Table 5)), and an other describing one partner desisting or waiving some behaviours in favour of the other during the intercourse (Desist; see 13, Table 5). The Agreement set was con formed also by a prior Submission item.

Conversely, regarding the accurate elements of the theoretical proposal, three factors corroborated the the oretical model in the exact same consideration: Spiritu ality, Instrumentality and Emotional Attachment (see results 6, 10 and 15, respectively, Table 5).

Finally, focusing on the weakest results of the anal ysis, we found an isolated item of Self-presentation (see result 12, Table 5), indicating the social status held by partners after the intercourse, and a last facet with Vari ability and Reproduction items (see result 14, Table 5), apparently sharing the meaning on purpose or motiva tion for sexual intercourse, to the Variability definition as discussed.

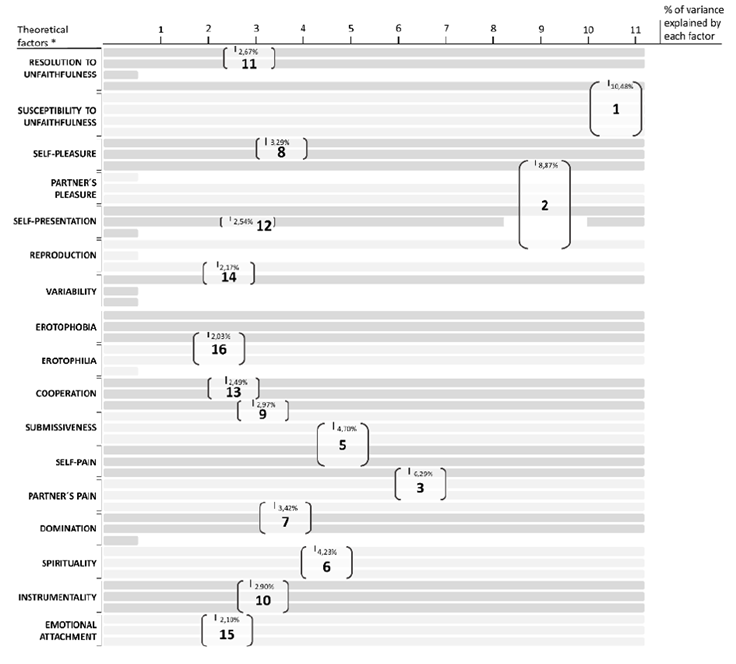

Figure 1shows the final allocation of every compo nent in a scale from minimum to maximum percentage of variance explained in the analysis. It provides a compre hensive picture of the evidence obtained along with the modifications of factor compositions, easing comparisons between the theoretical model and the empirical outcome.

Essentially, the quantitative analysis specified the theoretical factors in terms of the participants’ answers, achieving a more accurate picture of the real boundaries within the schemata applied by individuals.

5. Conclusion

In this study we report a second stage to overcome the actual lack of consistency among studies on sexual be liefs by introducing a set of results based on data col lected within the frame of theory disambiguation and unification, gathering a wide range of approaches.

Note. *Numbers matching to final outcomes from EFA (Table 5). Factor 4 was excluded after discussion on Erotoph/ results.1: Susceptibility to unfaithfulness; 2: Pleasure focus; 3: Pain focus; 5: Submissiveness; 6: Spirituality; 7: Domination; 8: Self-pleasure; 9: Agreement; 10: Instrumentality; 11: Resolution to unfaithful ness; 12: Self-presentation; 13: Desist; 14: Variability; 15: Emotional attachment; 16: Erotoph/.

Figure 1 Comparison between Theoretical Model and EFA Results

The quantitative result concerning the present report constitutes a key step to validate the theoretical model which, indeed, exposed the necessity to include some changes to improve the understanding of sexual behaviour appraisal and the self-oriented goals of individuals.

In short, this effort provides a comprehensive picture of sex cognitions constrained by an accurate definition of what can be identified as a cognitive schemata, revealed after a process of concept disambiguation, and a whole set analysis.

For all aforementioned reasons, we consider the model of SO-CSSB to be a good candidate to improve the qual ity of sexual research and the validity of its results. This increase in the quality of evaluations is believed a poten tial improvement in the development of more predictive models and tools in the research of human sex behaviour.

6. Limitations

Two main limitations must be mentioned about the study. The first one is the early stage of model development: as the present study is substantiated in a literature review (Velo & Ruiz, 2023), the actual lack of evidence within its terms hinders the model to be subject of further con siderations regarding the accuracy of the internal and ex ternal consistency of the factors when compared to other samples, or the prospective or retrospective prediction of some variables of interest. On the contrary, it introduces a quantitative set of results to support the consideration of the SO-CSSB model. Therefore, every conclusion must be regarded within a preliminary stage scope.

Secondly, regarding to the sample, a larger group for the EFA, and an addition of a second sample to test the model in a confirmatory analysis, would be desirable to set a more robust model. On the same line, different samples may be relevant to test the general character of the model, and if is equally applicable to every popula tion as it is designed.