Introduction

A characteristic of today's post-modern societies associated with the consolidation of the neoliberal economic model is the importance of consumption as a driver of the economy and economic development. In Chile, the neoliberal model produced a redesign of the borders between the market and the State (Madariaga, 2020), changing culture and the relationships between social groups in which consumption became a structural foundation of identity and status definition, with practices that appear closely linked to personal identity, social belonging and life satisfaction and the feeling of happiness or discomfort, both key elements of subjective well-being (Araujo & Martuccelli, 2013, Denegri et al., 2007; Berger & Heath, 2007; Dittmar, 2008). Additionally, individualism and competition are now associated with success and satisfaction with life as by-products of the material success that the same system requires (Denegri, 2019; Denegri et al., 2014a).

This process has impacted generations of Chileans that have grown up with the implementation of the neoliberal model and especially the generations that were born in it -adolescents, and current young adults- in whom materialism and impulsivity play an important role at the moment of purchase (Castellanos et al., 2016). An example of adolescent behaviour and its relationship with consumer society and the impact of the neoliberal logic it is observed in how shopping centres have managed to position themselves as a space for social encounters, and the dispute and construction of identity (Bermúdez, 2008). Here, the identity construction rises, to a large extent, on the basis of inclusion-exclusion systems that configure identity in adolescents’ and youths’ individualization processes. This is one of the consequences of a neoliberal model that’s been assumed in recent decades by countries in Latin America with great economic, political and cultural consequences in Chile (Garretón, 2012; Larraín, 2014; Madariaga, 2020). In this scenario, young and adolescents form an increasingly attractive market segment, and many technological marketing strategies are oriented towards influencing and impacting their consumption patterns (Arias & Rodriguez, 2021; Zmuda, 2011). Adolescents are also some of the most frequent visitors to malls, spending significant amounts of time and money there, buying clothes and food, and the marketers are investing increasing amounts of research money in efforts to find ways to appeal to the consumer behaviour of young people (Shim et al., 2011; Spasova & Gundasheva, 2019). This is especially important considering that it is in this stage of life that consumption practices become consolidated, especially the linking of these with the adolescent's construction of his/her identity and with the notion of the roles that he/she must play (Ersoy-Quadir, 2012). (Isaksen and Roper. 2012) have described that in this stage, self-esteem is “mercantilised” very effectively. These authors argue that young people may seek stability and try to “fit in” with the world and with their peers through the opportunities offered by consumption as this stage in life is seen as a moment of “crisis and confusion” in their development where they experience high levels of insecurity and doubt. This way, adolescents generate more permanent behaviour patterns that will accompany them throughout their adult lives.

At the same time, and as a result of the change in upbringing patterns and the greater independence enjoyed by children and adolescents, it is observed that the young have great influence in the consumption decisions of their families, have their own money and take independent decisions on how to spend it from an early age (Barros et al., 2019; Denegri, 2019; Denegri et al., 2008; Fromm & Garton, 2013; Palan et al., 2010; Singh & Nayak, 2014). Different authors have taken different positions regarding this subject. Some, like (France. 2000), state that the young are active and reflexive in their consumption habits and therefore not easily influenced. Others, however, say that even if we suppose that the young are in some way inherently resistant to market pressure, we may be forced to the conclusion that this resistance does not appear to have been very successful, as many young people continues to participate so enthusiastically with the principles that underpin the consumer society (Croes & Bartels, 2021; Winlow & Hall, 2006).

(Oyeleye 2014) considers that adolescents have been particularly affected by the impacts of neoliberalisation, since they are especially defenceless compared to other generations. This is because their own parents have submitted and become dependent on the consumer society, and thus the young are being educated mainly as consumers and not as citizens (Giroux, 2014; Mandel et al., 2017). There is nothing surprising in this, since a recurrent theme of modern consumer culture is that happiness is for sale in the shopping centre, the internet, or a catalogue (Kasser, 2002).

Materialism in the young

Materialism, or the presence of material values, has been defined as the belief that success and happiness in life depend on material goods, i.e., the importance and value that individuals assign to possessions (Belk 1985; Chan & Prendergast 2007; Clark et al. 2001; Ravhuhali, 2020; Richins 1994). Thus, although the accumulation of material possessions may be an end in itself, it is also seen as a means of achieving goals related with self-definition and self-realisation, in which the value attached to possessions is related with the expression, maintenance and consolidation of a person's self-concept (Belk 1985; Czikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981; Hausen, 2019; Kasser & Kanner 2004). Thus, people with high material values not only focus on the acquisition of goods, they also construct beliefs on the psychological benefits that these can bring (Dittmar et al., 2007; Kasser et al., 2007; Yu-Ting & Qing-Qi, 2020).

Studying the impact of materialism in adolescence is especially important in a context where it is observed that materialism among the young, who attach great importance to money and to possessing expensive articles, has increased over the generations, reaching a peak in the late 1980s and early 90s with Generation X. It has since remained at a historically high level down to the present generation, the Millennials, born after Generation X (Janos & Ágnes, 2020; Maras et al., 2015; Twenge & Kasser, 2013). Other studies have shown that being rich is the highest aspiration of many adolescents and even primary school children (Brown & Kasser, 2005; Schor, 2004) and found between and buying-shopping disorder severity and materialism (Estévez et al., 2020).

Adolescence is a period of important developments which include biological, psychological, and social changes that make young people feel particularly vulnerable to the positive and negative effects of social pressure (Loureiro, 2020; Maras, 2007; Maras et al., 2012). The evidence indicates that in this stage, while fears related with physical threats (such as dangers and punishments) diminish, those linked with social evaluation, acceptance and success increase strongly and that the relationship between social influence and maturity is dependent on the nature of the social influence and gender. (Ahmed et al., 2020; Westenberg et al., 2004). Thus, in this period of greater social vulnerability adolescents are more susceptible to the social influence of peers, and especially to the context of consumption in which they live (Pechmann et al., 2005; Truman & Elliott, 2019). This leaves them exposed and vulnerable to the pressure of ever more aggressive marketing campaigns aimed at this segment, which help to increase the presence of materialist values.

Evidence from a variety of sources focuses on identifying the correlates, determinants, predictors and possible variables for moderation and mediation in the development of materialism in adolescents. Among others, it has been observed that those who overvalue money and material possessions run a greater risk of poor psychological health (Dittmar et al., 2014; Kasser 2002), low self-esteem and low satisfaction with life (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2002; Janos & Ágnes, 2020; Kasser & Kanner, 2004).

There are two measurement scales which have traditionally been used to understand materialism in adults (Belk, 1985; Richins & Dawson, 1992). One of the most frequently used is the Material Values Scale (MVS) of (Richins and Dawson. 1992), structured in three dimensions: centrality, success, and happiness. The first dimension refers to the central importance adopted by the acquisition of possessions, in comparison with other personal goals; the second is linked with the tendency to judge one's own and other people's achievements as a function of the quantity and quality of material objects accumulated; and the last to the belief that the possession of material goods is an essential condition for well-being (Denegri et al., 2014b). In the specific case of adolescents, (Goldberg et al. 2003) developed a scale oriented towards this segment, using language and contexts more easily understood by young people.

Materialism and Satisfaction with life

Numerous studies in adults have found a negative association between satisfaction with life and materialism, whether operationalised as a personality trait (e.g., Belk 1985) or as a value orientation (e.g., Richins & Dawson 1992). Most previous studies suggest that materialism makes people unhappy (Solberg et al., 2004; Castellanos et al., 2020), other research suggests that unhappiness may promote materialism, and that material possessions can fulfil a defensive function when individuals suffer anxiety (Sheldon & Kasser, 2001).

In a review of more than 1,200 effect sizes by (Dittmar et al. 2014), it is shown consistently that materialism, however measured, is related with lower personal, financial, and social well-being. This negative association has been found in different countries and cultures, and in different age groups, in levels of education, and socio-economic condition. Analysis of the moderators showed that the strength of the effect depended on certain demographic factors (sex and age), the value context (study/work environments which support materialist values and cultures which emphasise affective autonomy), and prevailing cultural economic indicators (differential economic growth and wealth). Analysis of the mediators suggested that the negative association can be explained by poor psychological satisfaction (Betul & Zerrin, 2020). Other explications show the two dimensions of materialism-success and happiness-may influence life satisfaction differently (Sirgy et al., 2021).

An important issue to take in consideration is that studies of materialism tend to focus on adult populations, nevertheless, the study of materialism on younger populations is relatively scarce. For example, several studies have focused on the study of materialism of higher education students and young adults (Adib & El-Bassiouny, 2012; Chaplin & John, 2010; Durvasula, & Lysonski, 2010; Goldberg et al., 2003; Karabati & Cemalcilarb, 2010; Lučić et al., 2021), however similar studies can barely be found on younger populations. Therefore, the present work explores materialism on adolescents.

Regarding the study of materialism and its association with other variables, some studies have found negative correlations between materialism with emotional and behavioural problems (e.g., Gupta & Singh, 2019; Flouri 2004), pathological consumption behaviours (e.g., Dittmar 2005, 2007; Harnish et al., 2019), and greater participation in risk behaviours (Auerbach et al., 2009; Livazović & Jukić, 2017). In a similar manner, studies have found that a negative association between materialism and satisfaction with life, and that this association is stronger in individuals whose ideal acquisitive power and social status differ considerably from their ideal ones, a fairly frequent situation in lower income segments (Chan & Prendergast, 2007; Howell & Hill, 2009; Howell et al., 2012; Kasser et al., 2014; Ravhuhali et al., 2020). Lastly, other studies have found a significant negative association between materialism with satisfaction with life, emotional well-being, subjective vitality and self-realisation, and said associations are mediated by the satisfaction of psychological needs and personality (Chen et al., 2014; Górnik-Durose, 2020). Since these studies focused on adults, the present study aims to test if similar effects could also be found in younger populations while considering into account the particularities of said age group.

Attitude towards money as a mediator

According to (Belk, 1985), highly materialistic individuals tend to experience a greater negative affect and a lower positive affect than less materialistic people; they therefore tend to be more concerned about their social image, which is projected through the use of material goods, and to value their possessions for their utilitarian and social benefits, rather than for the pleasure and/or convenience that they offer (Richins & Dawson, 1992). This association is explained by some authors as by individuals spending a large part of their time and energy acquiring, possessing, and thinking about material things, and worrying about getting more possessions and therefore more money (Denegri et al, 2021; Durvasula & Lysonski. 2010) Prioritising money over other values such as personal development can lead to low levels of well-being, to sickness, and in extreme cases to pathologies (Inseng et al., 2021; Richins & Dawson, 1992; Tatzel, 2002). It seems reasonable to believe then, that materialism would be inversely associated with a persons’ well-being only if there is a high preoccupation with money.

In this regard, it could be argued that money is even more important for materialistic people since money would not only be a mean by which they obtain desired goods (Durvasula & Lysonski, 2010; Janos & Agnes, 2020), but is also vested with various meanings and attributes which go beyond its economic function (Aknin et al., 2018; Luna-Arocas & Tang, 2004; Matz et al., 2016). (Christopher et al. 2004) and (D’Ambrosio et al. 2020) found that they need a larger income to satisfy their needs when compared to less materialistic individuals. With this in consideration, the present study aims to test to what extent materialism is associated with well-being (measured as life satisfaction), and the extent to which attitudes toward money mediates the association between the two.

Peer influence as a Mediator

During adolescence, peer influence play an important role on identity construction and affirmation in general, but it has been found that it may also play a relevant role on the formation of consumption values and purchase decisions (Sirgy et al., 1997). In detail, studies have shown that communication with peers has a positive effect on the adolescents’ motivation for consumption and with the development of materialistic values, correlating with awareness of and loyalty to brands and fashion, and impulse buying behaviours (Churchill & Moschis, 1979; Luo, 2005; Mangleburg et al., 2004). These findings suggest that susceptibility to peer influence may also affect specific domains of adolescents’ lives.

Moreover, studies have found that peers influence may affect an individual’s materialistic values through peer pressure. According to some authors, adolescents can enforce material conformity by objectively influencing peers (Wooten, 2006), but also peer influence could be part of perceived peer pressure by, for example, feeling the need to right kind of clothes and possessions to fit in the group of peers (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008; Richins, 2017), which in turn could be associated with the development of materialistic values.

Susceptibility to the normative influence of peers reflects a desire to fit in and be accepted (Inguglia et al., 2019; Wooten & Reed, 2004), a particularly important concern of adolescents. It could be expected then that adolescents with highly materialist values would be more concerned about social comparison and are more susceptible to peer influence, paying a lot of attention to approval or disapproval of what they buy (Barros et al., 2019; Kasser & Kanner, 2003); they will also be more inclined to compare their possessions with those of their friends (Chan, 2007; Likitapiwat et al., 2015; Moschis et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2008) and identify more with celebrities (Engle & Kasser, 2005; Opree et al., 2012, 2013).

Considering the above, the present study aims to test to what extent susceptibility to peer influence mediates the association between materialism and well-being.

Objectives and hypotheses

Considering the studies reporting associations between materialism with subjective well-being, and with attitudes towards money and with peer influence, and the relevance of the latter in adolescents’ identity construction, the present study aimed at testing the association between materialism and satisfaction with life in a sample of Chilean adolescents, while also testing the possible mediation effect of attitudes towards money and peer influence in said association.

To address the main objective, the study defined the following specific objectives: a) to describe the associations between materialism, attitudes towards money, susceptibility to peer influence, and satisfaction with life in Chilean adolescents, b) To identify the direct effect of materialism on satisfaction with life in Chilean adolescents, c) To identify the indirect effects of materialism on satisfaction with life in Chilean adolescents through mediation of attitude towards money, through attitudes towards money and peer influence (in series), and through peer influence (only).

Based on these objectives, the following hypotheses are proposed. With respect to the direct effect of materialism on satisfaction with life in Chilean adolescents, an inverse association is hypothesised between the two variables, meaning that individuals scoring high on materialism will present lower scores of satisfaction with life, and vice versa.

Three hypotheses are proposed in regards of the indirect effects of the mediator variables: attitudes toward money and peer influence. First, it is proposed an indirect effect of materialism on satisfaction with life, mediated through attitudes towards money. Consequently, a positive association between materialism and attitude towards money is expected, as well as a negative association between attitudes towards money and satisfaction with life.

Regarding the indirect effect of materialism on satisfaction with life through attitude towards money and peer influence (acting in series), two further hypotheses arise. First, a positive association between attitudes towards money and peer influence, and a negative association between peer influence with satisfaction with life.

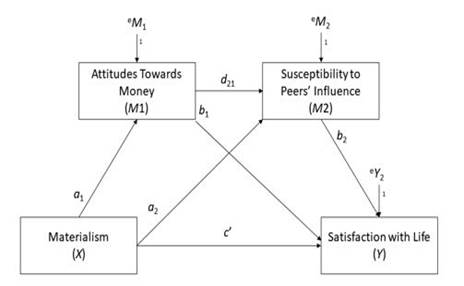

Lastly, regarding the indirect effect of materialism on satisfaction with life, through peer influence, a positive association between materialism and peer influence is hypothesised (see Figure 1).

In view of the importance of materialism in post-modern societies, this phenomenon has been widely studied, but specifically in adults, with relatively scarce research being done on younger populations. To address this gap in the literature, the present study followed a quantitative approach, with a non-experimental transactional design. To do this, the validity of the scales was assessed first, secondly the direct association between materialism and satisfaction was assessed, as well as the indirect effect while mediated through attitude towards money and peer influence.

Method

Design

The present study followed a quantitative approach, with a non-experimental transactional design, and a correlational-explanatory scope (Hernández-Sampieri and Mendoza-Torres, 2018). The study consisted of a questionnaire for Chilean adolescents exploring their materialism, attitudes towards money, susceptibility to peer influence and satisfaction with life that was answered by each participant at a single point in time. The hypothesized model was based on evidence found in the scientific literature regarding the association between the variables and was tested following the guidelines by (Hayes. 2013) for conditional process analysis and its implementation for mediation testing.

Participants

The population consisted of Chilean adolescents of the cities of Temuco (southern Chile), Santiago (centre) and La Serena (northern) enrolled in their first or second year of secondary education.

The sample, obtained by two-stage non-probabilistic sampling by conglomerates, consisted of 1325 pupils (54% girls, 46% boys), between 15 and 16 years old (Mage=15.4 years, SDage=.8).

Instruments

Satisfaction with Life Scale for Students developed by (Huebner. 1991). Comprises 5 items in a Likert format of 1 to 7, with 5 specific domains for satisfaction with life: family, friendships, school, satisfaction with “self” and satisfaction with place of residence. The internal consistency of the measurement was adequate (Cronbach's alpha =0.79).

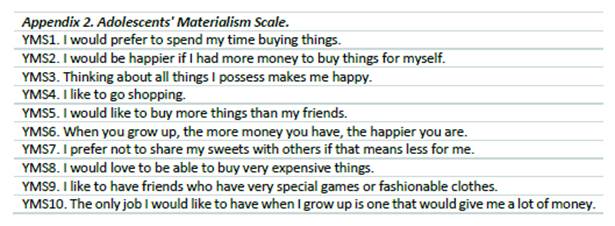

Adolescents' Materialism Scale, developed by (Goldberg et al. 2003) for application to adolescents aged up to 15 years old. The scale reflects different materialist values, expressed in questions such as “I would be happier if I had more money to buy more things for myself” or “the only job I would like to have when I grow up is one that would give me a lot of money”. The scale is unifactorial and consists of 10 items measured on a 6-point Likert-type scale which varies from 1: totally disagree to 6: completely agree. The internal consistency of the measurement was adequate (Cronbach's alpha =0.76).

Attitudes towards Money Scale, developed by (Luna-Arocas and Tang. 2004). Consists of 17 items in 4-point Likert format which varies from 1: strongly disagree to 4: strongly agree; the items are organised in 4 dimensions: Happiness, Freedom, Power and Bad, reflecting two factors: (i) the social factor, made up of six items related with the power of money in social terms, i.e. having more friends, being more respected, influencing others, having a good image, etc.; and (ii) the personal factor, related with personal desire to obtain wealth and with the subjective happiness and well-being that money provides. This scale has previously been used in studies with young Chilean university students, showing adequate internal consistency (Denegri et al., 2012). The internal consistency of the scale was also adequate (Cronbach's alpha =0.82).

Susceptibility to Peer Influence in Consumption Scale. Originally developed by (Bearden et al. 1989), consists of 2 dimensions: the first, called normative influence, can be divided into a significative value and a utilitarian value. The former is the human tendency to behave based on other people's expectations in order to improve one's self-image (significative value) or to earn rewards or avoid punishment (utilitarian value). The second dimension, called informational, is associated with the human tendency to accept information from others as evidence of reality. In this work we use the reduced version for adolescents adapted by (Zhang. 2001). It consists of 6 items which measure susceptibility to the normative influence of peers using a 6-point Likert scale varying from 1: totally disagree to 6: completely agree. The internal consistency of the measurement was adequate (Cronbach's alpha =0.88).

Procedure

In stage 1 a list of secondary schools located in the cities where the study took place was made, from this list one third of schools were selected at random (first conglomerate). Formal contact with the selected schools’ directors was made, detailing the aim of the study and inviting them to take part in it. Those who agreed were asked to authorise the application of a battery of instruments, in the form of questionnaires, to all pupils in first and second year of secondary education (second conglomerate consisting of complete year groups). To formalise the authorisation, the director was asked to sign a consent for the participation of the pupils in the school.

Once authorisation to apply the instruments had been obtained, the class teachers of each group were contacted to coordinate a date for application. Direct contact was made with the classes to explain to the pupils the objectives of the investigation and the criteria of confidentiality and voluntary participation. The parents of the students who agreed to take part in the study were contacted prior to data collection by sending them a letter of presentation and an informed consent form detailing the main aspects of the study including but not limited to objectives, variables, scope, ethical guidelines, researchers’ contact information. It was required that parents signed the informed consent form and the students the assent form prior to them start answering the questionnaire. Data collection took part during class times for all students of the class who agreed to take part in the study and had the consent forms signed by their parents.

The data derived from the quantitative section of the batteries was transferred to the database for statistical analysis, carried out with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 23.

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Universidad de La Frontera under the research protocol number 038/15. The ethical guidelines of the study include the voluntary nature of the students’ participation, their right to stop participating at any point of the study. Taking part in this study did not entail any risks regarding participants’ physical and psychological wellbeing. Participants did not receive any incentives for taking part in this study. These guidelines were presented to the participants and their parents in the respective informed consent and assent forms.

Data Analysis

Prior to the main analyses if the study a set of descriptive analyses were conducted to check the quality of data as well as a set Confirmatory Factorial Analyses (CFA) was conducted to validate the scales. The main analyses of the study consisted of testing the theoretical model hypothesised in Figure 1 using the PROCESS macro developed by (Hayes. 2013), which allows testing mediation models by bootstrapping with SPSS. Thus, for the mediation test simultaneous regressions were carried out of the direct (independent variables on dependent variables) and indirect effects (independent variables on dependent variables through the mediator variables) as per (Preacher & Hayes. 2004).

Results

The present study aimed at testing the association between materialism and satisfaction with life in a sample of Chilean adolescents, while also testing the possible mediation effect of attitudes towards money and peer influence in said association. Prior to the main analyses of the study a set of descriptive analyses were conducted followed by CFA to ensure quality of the data and measures used in the study and to validate the scales. To test the study’s hypotheses the theoretical model presented in Figure 1 was tested using mediation analyses. Results of these analyses are presented below.

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive analyses. The satisfaction with life scale presents a mean of 27.7 (SD= 5.0, range 9-35); the materialism scale presents a mean of 15.3 (SD= 5.2, range 5-30); the susceptibility to peer influence in consumption scale presents a mean of 11.8 (SD=5.5, range 6-36) and the attitude towards money scale presents a mean of 11.5 (SD= 3.9, range 6-24). It is worth mentioning that the scales included only those items selected after the factor analysis.

Regarding the associations between variables, satisfaction with life showed a negative correlation with the other three scales: (r = -0.110, p <0.01) with materialism, (r = -0.156, p <0.01) with attitude towards money and (r = 0.083, p <0.01) with peer influence. The direction of these associations turned as expected.

Materialism showed a positive correlation (r = 0.475, p <0.01) with susceptibility to peer influence and with attitude towards money (r = 0.597, p <0.01), which also presented a positive correlation with each other (r = 0.425, p <0.01). See Table 1 for more details regarding the descriptive results.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and Pearson's correlation of the scales.

** Correlation is significant at 0.01 (bilateral)

Confirmatory Factor Analysis. After verifying the structure of the data, we used CFA to validate the scales. The items of all the scales presented significant factorial coefficients for the constructs they were intended to measure, in detail: between .56 and .71 with CR .79 for Adolescents' Materialism Scale; between .71 and .83 with CR of .88 for Susceptibility to Peers’ Influence; and between .52 and .80 for Attitudes Towards Money with CR .81 for Personal Happiness subscale, and with CR .69 for Social Power subscale); the fit between the models estimated and the data observed is quite good. This may be observed in Table 2, which shows the values of the indicators resulting from the CFA for the 3 scales.

The Adolescents' Materialism Scale consisted of 6 items; YMS1, YMS2, YMS5, YMS6, YMS8 and YMS10; while items YMS3, YMS4, YMS7, and YMS9 were eliminated (see Appendix 1 for more details regarding the items of this scale). The Susceptibility to Peers’ Influence scale consisted of 5 items; only SUSCEP5 was eliminated (See Appendix 2 for more details regarding the items of this scale). Lastly, the Attitudes Towards Money scale consisted of 2 subscales: Personal Happiness which comprised items EAD6, EAD8, EAD13, and EAD14; and Social Power which comprised items EAD2, EAD10 and EAD11 (See Appendix 3 for more details regarding the items of this scale)

Regarding results of the goodness of fit indexes, values of the RMSEA for the Susceptibility to Peers’ Influence and Attitudes Towards Money resulted greater than .07 which according to convention would indicate that the model testes is unacceptable (not a good fit). Nevertheless, the SRMR values resulted close to .03 and the values for NFI, CFI, GFI, AGFI and IFI presented acceptable values, higher than or very close to .90, indicating a good fit (Hair et al., 2019). Complementary, chi-squared test (χ²/g.l) also resulted in values considered acceptable (close to .3) for Susceptibility to Peers’ Influence and Attitudes Towards Money, and a quotient of 2 for Susceptibility to Peers’ Influence, indicating a reasonable fit.

Table 2 Indices of fit for the factorial model of the YMS, SUSCEP, EAD scales.

χ² = chi-squared, χ²/g.l = ratio of chi-squared over degrees of freedom, NFI= normal fit index, RFI= relative fit index, CFI = comparative fit index, GFI= goodness of fit index, AGFI=adjusted goodness of fit index, IFI= incremental fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, SRMS = standardised root mean square.

* p < 0.01

Main analyses, mediation analysis

Regarding the effect of materialism on satisfaction with life, results of the total effect indicate a significant association between the two variables (c = -0.11, SE = 0.03, t = -3.96, p < .0001, CI = [-0.16; -0.05]), with the overall model for the total effect also resulting significant, R 2 = .01, MSE = .99, F(1,1290) = 15.66, p < .001. Accordingly, the direct effect of materialism over satisfaction with life also resulted significant (c’ = -0.02, SE = 0.04, t = -0.57, p = .57, CI [-0.09; - 0.05]), as well as the total indirect effect (c-c’ = -0.09, SE = 0.03, CI [-0.15; -0.04]). Overall, these results support H1 of this study.

To discover which of the three indirect effects (paths in the prediction model presented in Figure 1) contributes the most to the prediction of satisfaction with life, models were compared. Results for each indirect effect are presented next.

Results of the indirect effect 1 (a1*b1 = -0.08, SE = 0.02, CI [-0.13; -0.04]), which describes the prediction of satisfaction with life by materialism while mediated by attitudes towards money, resulted on a significant effect. In detail, the association between materialism and attitudes towards money resulted positive and statistically significant (a1 = 0.60), thus supporting hypothesis H1a of the study. Complementary, the association between attitude towards money and satisfaction with life also resulted statistically significant and negative (b1 = -0.14), and so hypothesis H1b of the study is also supported.

Regarding the indirect effect 2 (a1*d21*b2 = -0.00, SE = 0.01, CI [-0.01; 0.01]), describing the prediction of satisfaction with life by materialism while mediated by attitudes towards money and susceptibility to peers’ influence (in series), results yielded a non-significant association, thus H2 was not supported. In detail, the association between attitudes towards money and peer influence resulted statistically significant (d21 = 0.23), and so H2a is supported, but the association between susceptibility to peers’ influence and satisfaction with life (b2 = -0.01) resulted non-significant, so H2b is not supported.

Lastly, indirect effect 3 (a2*b2 = -0.00, SE=0.01, CI [-0.03;0.02]), which describes the prediction of satisfaction with life by materialism while mediated by susceptibility to peers’ influence, resulted non-significant, and so H3 is not supported. In detail, although the association between materialism and peer influence resulting significant and positive (a2 = 0.34) thus supporting hypothesis H3a, the association between peer influence and satisfaction with life resulted non-significant.

Regarding the contrast of indirect effects, effect 1 resulted greater than indirect effect 2 and indirect effect 3, neither of which are significant. This would mean that materialism has a greater effect on satisfaction with life while mediated by attitude towards money in isolation, and that this prediction works better than when the effect is mediated by susceptibility to peer’s influence alone, and with it in series.

To summarise, the results described above show that in general, materialism predicts satisfaction with life in adolescents by influencing their attitudes towards money. Considering the direction of the associations, this means that the more materialistic an individual is, less satisfied with their own life they will be, but this is explained by materialism boosting an individual’s positive attitudes towards money (positive association), which in turn has a detrimental effect on satisfaction with life negative association). Conversely, these effects are not present when considering susceptibility to peers’ influence.

Discussion

The relation between materialism and well-being has been arousing interest for a long time and has been the object of several studies. (Dittmar et al. 2014), in a meta-analysis with 257 different population samples in North America, Western Europe and Asia, concluded that materialism is negatively associated with personal well-being; a negative relation is invariably found between these constructs. However, no clear information is found on the strength, direction and consistency of the negative relation reported between the variables. In the same line of reasoning, another meta-analysis (Fellows, 2012) of 47 works which studied the association between materialism and well-being and its effect size in more than 39,000 people. This study found that there was a great statistical heterogeneity in the studies, and that the sizes of the effect varied widely. These results suggest that there are other factors influencing the strength of this relation. Based on the above, the purpose of the present work was to broaden the previous studies available on the association of materialism with satisfaction with life in Chilean adolescents, focusing on the strength of this relation and observing what other factors influence this dynamic to diminish or increase the strength of the association. To do this we examined the relation between materialism and satisfaction with life, seeking to identify the direct effects between the variables, and to identify the indirect when said association is mediated by other variables, namely, attitude towards money and peer influence.

The main finding of the study is the significant direct association between materialism and satisfaction with life. These results suggest that materialism is a predictor of satisfaction with life in adolescents when no other variables are considered. Another relevant finding relates to the association between materialism and satisfaction with life being mediated by attitudes towards money, which suggests that the inclusion of said variable improves de overall prediction of satisfaction with life when considering materialism as a possible predictor. Lastly, no evidence was found for a mediating role of susceptibility to peers’ influence in the association between materialism and satisfaction with life. Implications of these findings are discussed below.

In the case of peer influence, we found a significant, strong positive association with materialism. During adolescence, young people must consolidate a new identity and establish their independence from their parents. Therefore, they tend to identify with their classmates and friends who become the principal socialising agents of consumption values. These peers play an important role in the development of young consumers' preferences; previous studies have found that those who are more susceptible to the influence of their peers are also more materialist (La Ferle & Chan, 2008). However, as shown by the results of La Ferle and Chan (2008), when these variables are controlled, they do not significantly predict values of materialism suggesting that other factors such as attitudes, and judgements and beliefs about money probably play a more important role in predicting levels of materialism (than peer influence).

This was confirmed in our results, as we found that attitude towards money mediate the negative association between material values and satisfaction with life. These results coincide with the proposal of (Durvasula and Lysonski. 2010) that young people consider money a way to display power and status; therefore, what is acquired with money is very important, leading to a higher level of materialism and a greater impact on psychological well-being. Our results suggest that although a materialist desire for possessions is negatively associated with well-being, the strength of this association increases when other related variables are included, such as the value given to image and status, and the belief that money is a sign of success and happiness.

The results of the present study also coincide with those of (Dittmar et al. 2014), who say that materialism can be best conceived of as a group of beliefs and values, and not as a simple desire for money and material goods. This means that to identify the strength of the correlation between materialism and well-being, other measurements must be incorporated which evaluate materialist beliefs more broadly; we have tried to do this by including the relation with attitude towards money as a mediator variable.

As (Jacob. 1997) and other authors (Ersoy-Quadir, 2012; Schmidt & Marratto 2008) say, in post-modern societies the values associated with more traditional culture have been replaced by materialistic worldviews in which access to material goods determine human desires and objectives; establishing money as the means to accessing these goods, and thus to well-being and happiness. Furthermore, according to results of the present study, these beliefs appear to be present in adolescents as this study focused on a specific age range (mid-adolescence). Nevertheless, future studies should include other age ranges of adolescence since some works (e.g. La Ferle & Chan, 2008) propose that materialism reaches a peak in the early and middle stages of adolescence, when adolescents experience a decline in their self-esteem associated with construction of their identity and the abandoning of childhood beliefs. At the end of adolescence, self-esteem improves the tendency to use material possessions as a vehicle for self-definition probably diminishes. Longitudinal studies should also be considered which will reflect these changes.

In terms of limitations of the study, the main issue comes from the cross-sectional design used in the study. Overall, since cross-sectional designs only measure variables at one point in time and do not allow manipulation of a variables, it is not possible to definitively conclude a causal effect of materialism over satisfaction with life, nor with attitudes towards money. Considering this, the present study should be considered as initial evidence of these variables’ associations, but further research would be needed to infer causal relations. In this regard, we propose that future studies explore such design by implementing experimental o quasi-experimental designs.

In conclusion, this work contributes to knowledge of the presence of materialism and the influence of attitudes towards money in the conception of well-being and satisfaction with life of our young Chilean adolescents. Identifying this aspect is important for its future impact on their financial health and their well-being. People who present high materialist values have greater financial worries and poorer abilities for managing money, and therefore present a greater tendency towards getting into debt and impulsive and compulsive buying (Garoarsdótti & Dittmar, 2011).

It may be noted that these young people will shortly have access to credit cards and other financial instruments which will make it easier for them to spend beyond their means and encourage tendencies towards excessive buying and other behaviours like pathological gambling (Saldanha et al., 2018) and compulsive buying (Garoarsdótti & Dittmar, 2011). Therefore, there is a need to develop educational interventions designed to reduce the fixation of adolescents on the acquisition of money and possessions. Education must contribute to the awareness of these young consumers, helping them to reflect on how their purchase decisions may be influenced by their perceptions about money and the importance of possessions, giving them the tools with which to evaluate their actions critically, and helping to improve their financial well-being and psychological health in the long run.