Introduction

The classic tales or folk stories, commonly known as fairy tales, emerged from popular stories originally from an oral tradition that later transitioned into written and visual forms. Their objective was to teach lessons that would be reflected in the way one interacted with the world. These stories were very different from those we know today and changed over time to meet the needs of the audience and society. As they moved to the written genre, most of these stories were transformed for a bourgeois audience. As Lerer1 said, "The term fairy tale is a translation from the French conte de fées, a genre that emerged in the salons of the nobility to give a narrative stamp to social criticism and offer moral education with a layer of fantasy".

These stories are part of our lives, becoming visual, aesthetic, and moral references. Moreover, their written and visual versions become our guides for social interaction in a world governed by codes and visual symbols, as Hernández2 said. But, as Héller3 points out, the process of combining colors and experiencing them does not happen spontaneously. On the contrary, it results from experiences and associations that we make from childhood and that accompany us throughout our lives.

Over time, these stories have naturally evolved and adapted to socio-cultural changes. However, although new versions are generated, they retain elements of the previous ones keeping symbolic elements and messages maintained from generation to generation. The permanence of these stories in the visual culture has created these messages, and associations are maintained today. However, it must be considered that these obey symbolic relationships or socio-cultural associations, whose meanings are socially given, which generates changes in their reading according to the moment of interpretation. The relevance of the remakes or versions is that they are adaptations that obey a new reality that interprets the elements differently. The teachings are transformed, even though the formal elements representing it remain the same. These formal elements refer to the visual, tactile, or auditory components that constitute the structure and appearance of the work, including line, shape, color, texture, space, light, and sound.

For this article, an exploratory and qualitative methodology was used to analyze visual and written sources in order to determine the chromatic characteristics that remain in the images of these stories over time. For the visual analysis, specific colors and their relationship with adjacent colors were considered, as well as image analysis techniques such as those proposed by Harvard's Project Zero4 methodology, which is based on the analysis of artistic images and their relationships. In this methodology, the main element is critical vision, using analytical and artistic thinking to understand multidisciplinary issues by establishing connections and concepts from different areas, in this case, literature and image.

Through this analysis, semantic connections of color were established, linked to its formal treatment, which were directly related to social issues and human rights, allowing us to determine that although the images have changed, the color in most of these classic stories, which is distinctive of a character, remains, reinforcing the ideas that are associated with its meanings over time.

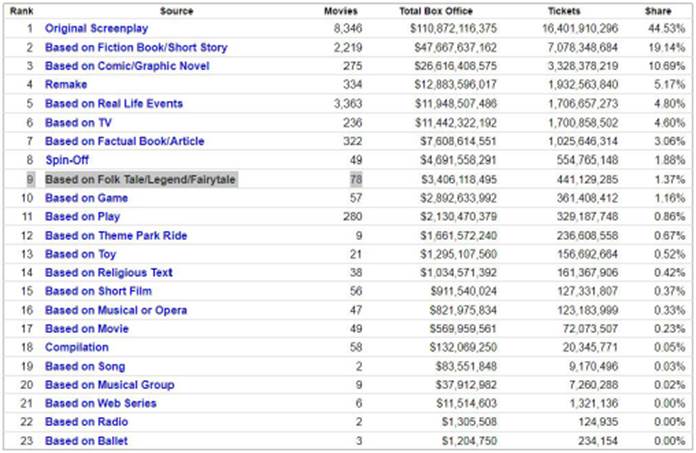

On the other hand, the increase in visual reading of these stories has been among the most viewed (see Figure 1). According to Zipes5 this growth is linked to social and cultural changes that create the need to use classic stories to emphasize or criticize these same changes, using the sociocultural connection inherent in these stories as communication tools and connections to people and their reality. As Julian Rodriguez and Andrew M. Clark 6propose, the ability to gather information is generated to achieve a visually coherent and impactful narrative.

Source: https://www.the-numbers.com/market/sources

Figure 1 Top-Grossing Sources 1995 to 20237 (2023)

Chromatic Associations

We can define our world with images; our way of learning is tied to a visual chromatic world and is one of the conditions that structure our perception of our surroundings. The image represents our world through signs and an iconic language in which we relate to reality.

Our reading and knowledge of the world are born from the experiences of our first moments of childhood. Therefore, following this logic, we could think that our chromatic relations are born from that moment. Some of the first images we relate to come from classic stories, with visual and imaginary images that develop narratives with specific lessons and messages. The visual elements we find in these images, such as lines, texture, or color, have their narrative personality associated with various social, political, or psychological readings that support the overall narrative of the image by reinforcing its meaning. In the case of color, its meaning is also related to how it is used. Depending on how it is used, we can tell whether the film is taking place in the past or the present, using, for example, black, white, or sepia as a time reference.

Classical folk tales are full of color associations to communicate the ideas and sensations of these elements', giving the stories a deeper meaning and emphasizing them. For example, we can see this condition in Snow White8:

Then they wanted to bury her, but when they saw that she was still as fresh as a living person and that her cheeks were still rosy and beautiful, they said: -We cannot bury her in the black earth-. So, they had a transparent coffin made of glass so that she could be seen, put her in it, and wrote her name and her status as a princess in golden letters.

Pastoreau9 said that in this text, we can see how color emphasizes certain ideas. Color is a pictorial partner to convey a specific idea to the viewer. Black earth has not the same connotation as red earth or yellow earth. In this case, the subject is affected by color, not only considering the color tone as a simple physical description of the object but understanding that black earth brings us closer to darkness, depth, loss, and death. Despite these characteristics, the feelings associated with black are ultimately conditioned by the experience of color and the social reading of it that defines what is "black". in a particular sociohistorical moment. In the nineteenth century, for example, this color was associated with esotericism and spiritualism, primarily with death, mourning, the occult, the desperate and the satanic.

Contrary to the ideas associated with black, pink cheeks indicate life and freshness, as the authors point out in the story of Snow White. This contrast generates the reaction that leads to the decision not to bury her. Color gives the scene additional information that helps us understand that there is still life in that body that is ready to be buried. In Snow White, color is a catalyst for experiences and ideas, so it becomes directly or indirectly a communicator. In these stories, color is used to emphasize intangible feelings or ideas associated with the point of view from which they are viewed.

Various color studies address these relationships, which can then be interpreted as messages transmitted unconsciously from generation to generation through the use of color in these stories. Two of the most relevant studies concerning classic tales are related to the social climbing and the sexual vision that Cavazotti Aires and Diogo10 explain in relation to sexual education and human rights: The first approach is the social-anthropological one, proposed by Propp11, who states that these stories are based on rites and evolutionary steps of society, arguing that the words of Snow White's mother are part of a ritual necessary for the birth of the girl. According to the author, the story teaches that this type of events in society, generates traditions that are necessary for change, growth, and evolution to occur. The second point of view is the psychoanalytic one, raised by Bettelheim12, who bases his explanation on the interpretation of the symbolic content of the stories using a sexualized point of view as a methodology of study:

The story begins when Snow White's mother, her finger, and three drops of blood slipping on the snow. Here, the problems of the story are already indicated: sexual innocence and purity are contrasted with sexual desire, symbolized by red blood. Fairy tales prepare the child to accept an even more traumatic fact: sexual bleeding as in menstruation or, later, in sexual intercourse, when the hymen is torn. Upon hearing the first sentences of "Snow White", the child discovers that the fact of bleeding - three drops of blood (three because it is the number most closely associated in the unconscious with sex) - is a precondition for fertilization since it necessarily precedes the birth of a child. In this case, the (sexual) bleeding is associated with a "happy" event; without further explanation, the child learns that no child - not even himself - can come into the world without this bleeding.

These associations generated by the use of color in the text are mainly transferred to the images. Although they are two different media for symbology, color retains this characteristic in both text and image. As a result, the symbolic meanings given in the text can be similarly or equally conveyed by the color in the image.

These meanings are presented differently in the same image, depending on the part of the image. Barbara Flueckiger13, in her research Timeline of Historical Film Colors, shows that the different techniques and the search for results related to color in cinema over time were aimed at showing the colors of reality, thus trying to identify or give color in the images that were part of the representation of scenarios and objects. It was in the backgrounds and elements of the scene that a mimetic reading of color was sought. However, in terms of characters and environment, as Nathalie Kalmus14 states, what was intended to show through color was the representation of emotions:

By understanding the use of color, we have found that we can subtly convey dramatic moods and impressions to the audience, making them more receptive to whatever emotional effect the scenes, action, and dialog are trying to convey. Just as each scene has a certain dramatic mood -some emotional response that it seeks to evoke in the minds of the audience- so each scene, each type of action, indicates a color that harmonizes with that emotion.

As mentioned earlier, these stories supported a social message. Most of them have a normative background to their images, which clarifies the enunciation and chromatic denotation of the stories. It is possible to harmonize this with our social perceptions to make them identifiable and valuable elements for society, such as human rights principles.

In the case of Snow White and Alice, it is essential to know that colors are also linked to the psychological components generated, that these tonalities have a semic value generated by other connections, achieving that this association given by society can be transmitted through the color in the image, as Hernández15 said. This transmission of concepts and ideas is presented thanks to the transversality of color, that is, having the peculiarity of being able to remain in the images as a characteristic element of them. The color in the classic tales has remained in time, either because it is transferred from the text, as in the case of Snow White's white skin and red lips, or because it is transmitted through visual culture, as it may be the yellow hair and the blue with the white color of Alice's dress.

The color is presented as a transversal element while continuing to transmit messages already associated through the chromatic characteristics. These messages can be the same from the beginning, being able to be something found in the original story and transferred in the image, and that can change according to society. As said by Hernández,16 the real challenge is to understand the ability to adapt, control and understand what happens with the information maintained and reinforced among so many versions and new data.

The image presented below is a color association developed by Nathalie Kalmus (Disney color consultant on the Technicolor processes used in the animation in these stories and whose concepts are based on most of the films).

Source: DEastmanhouse.org- technicolor 100.

Figure 2 The chart shows the expressive equivalent of the color used on the screen and the relationships the viewer creates through them

However, our chromatic associations come from our relationship to the world. Therefore, physical, scientific, and psychological relationships are always present in understanding a color in its environment. John Gage17 in "Color and Culture," Brusatin18 in "History of Colors", and Eulalio Ferrer19 in "The Languages of Color" introduced us to the idea of a relationship between society and color. There is a reciprocal relationship between how we see reality, how we use color, and how we perceive our surroundings. How we relate to color depends on our relationship to the world, so much so that the use of color helps us identify imminent danger, time periods, characters, and social groups.

Chromatic narrative

When examining the images of classical tales, we must take into account a preexisting visual culture from the same story because these classic tales are stories that have been preserved in time and passed down from generation to generation. They transmit to us, through their elements and images, different informative codes. According to Brusatin20, there are physiological, physical, and subjective colors. Each of them has particular characteristics depending on the field in which the color is analyzed. In the field of visual and plastic arts, all these elements must be considered without making a precise distinction between them, because, at the moment of perceiving a color, we do not differentiate between the physical or psychological effect. We simply read the image with everything that comes from it.

This is where the concept of color transversality becomes relevant. Through the transversality of color, as Hernandez21 said, we can explain and understand the ability of color to move from one medium to another over time without losing its narrative essence. Hernandez22 said that transversality allows the chromatic conjunction of denotative (descriptive), connotative (meaning associations), and temporal values that are conveyed through the associations generated by society when seeing color in the context of the image. This is how the chroma within the image is given its meaning, which is reflected in the final perception of the image.

Society gives these associations to color. However, much of this association is generated by our experience of color; just as our experience is influenced by the way we read color.

Although we cannot deny the importance of environmental elements: lineal forms, objects, people or animals, and their influence in the narrative of the image, it is also difficult for us not to accept that the way the image is colored expresses to us much more than what we see at first glance. It is no longer a matter of looking at each pictorial element separately, as we do when discussing color. Instead, when we perceive the image, everything in it tells us a story: the medium, the texture, the color, and the line converge to signify, to form as Hernandez23 said the narrative of the image.

Source: DeviantArt. https://www.deviantart.com/fdasuarez/art/Poisoned-apple-265145500

Figure 4 Poisoned apple by fdasuarez on DeviantAr. (October 25, 2011)

The color in this image allows us to identify the person depicted. The use of the spectrum of white, red, blue, and black enables us to identify this young woman as Snow White, the princess from one of the Brothers Grimm's classic tales. No other person could have those blood-red lips, ebony black hair, and skin as white as snow. So, without a doubt, this is Snow White.

Color in Snow White

In 1812, The Brothers Grimm published the story of Snow White, which has been illustrated in several ways. However, the most popular and widely known visual representation of the story is the 1937 Disney version. Disney defined the colors and clothing of Snow White, becoming the story's visual reference and defining its chromatic aspect. Snow White has become a sociocultural icon that merges the figurative elements of fairy tales. Michel Pastoreau24, in his book "The Colors of Our Memories" points out that red, white, and black are "the three polar 'colors' of ancient cultures, around which the majority of their tales and fables are built, and which are presented in color."

The chromatic analysis of the Snow White's images reveals the use of two-color techniques: one for the background and another for the main characters or elements. The background color is presented in more neutral tones, with adjacent colors creating a close color range and a specific atmosphere. The characters are treated with monochromatic tones without gradients or hue changes. The colors used on Snow White's character represent her state of purity and evolutionary status as a princess.

From a psychological point of view, it is clear that in the beginning we associate the character with innocence and purity, without forgetting that the use of brown was also associated with servitude and proletarian classes. In other words, at the beginning of the story, we are confronted with a reality that defines the personality and status of the main character.

Credit: George Eastman House Moving Image Collection. Photograph of the nitrate frame by Barbara Flueckiger. Barbara Flueckiger. In Timeline of Historical Film Colors.

Figure 5 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Walt Disney, 1937)

Credit: George Eastman House Moving Image Collection. Photograph of the nitrate frame by Barbara Flueckiger. Barbara Flueckiger. In Timeline of Historical Film Colors.

Figure 6 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Walt Disney, 1937)

Throughout Snow White's story, a figure characterized by her nobility, kindness, and innocence, we can find a constant reference to the red color. It certainly fulfills a narrative role through its constant presence and how it is related to elements with which it is identified, creating a sequence for the viewer and showing the evolution of the story from the birth of the girl to the end of the story. As Miguez25 said, "Some authors, such as Sawyer (2011), have even seen a correlation between the progress of Snow White and the advancement of women's rights". Before the release of Tangled and Frozen, this author argued that these princesses could correspond to the three waves of the feminist movement through the analysis of Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty and the Beast, and The Princess and the Frog. At present, we can also associate it with the fundamental right to transparency and access to public information, how white, how pure, how transparent a nation should be, thanks to access to information. This empowers its citizens to build their country26.

Color in Alice in Wonderland

This story, written by Lewis Carroll, can be characterized as a process. It is an evolutionary journey visually marked by chromatic symbolism. The evolution of the journey, marked by the encounters she has with different characters throughout the story, is the metaphor for her psychological growth and, ultimately, the path to maturity, forcing the use of intense colors that characterize not only Alice but her way of seeing the world.

When we look at the color in the images of this story, we must also look at the time and moment of its creation. This is because these elements explain the specific characteristics of the story. In this case, it was possible to identify a reflection of England's Victorian society of the 19th century. Regarding color, historical facts also influence the technique and philosophy of color in a specific way. The concept of color is undoubtedly closely linked to that of Kalmus, where a relationship of color with reality and immaterial meaning is established. However, as mentioned above, the creation of Disney's Alice was also a process presented in terms of the management of color and image.

First of all, it should be clarified that Disney was not the first person to give Alice her characteristic blue color. An earlier version of the girl with her blue dress and blonde hair, published by Thomas Crowell in 1893, had already been established. However, the Disney version made an impact with the color and its representation in 1951.

In 1941, Walt Disney and several artists from his studio went on a two-and-a-half-week tour of Latin America, a trip paid for by the US Government. It was the time of World War II, and the administration of then-President Franklin Roosevelt took a dim view of the growing influence that Germany and the Axis powers were having in Latin American countries, so to reverse the situation, they send their best ambassador: the now world-famous Walt Disney, as Arcas27 said.

Mary Blair, the artist who did Alice's illustrations, participated in this Disney journey. Her illustrations were not used in the film, but her style influenced its aesthetic. Latin America greatly influenced Blair's conception of color. A new palette of more saturated colors contrasted with opposite colors and vibrant combinations influenced the new palette in her next creations, including Alice in Wonderland.

This Latin American influence marked a radical change in the conception and management of color in the illustrations of this story. The variety and intensity of colors sought a symbolic world inherited and transmitted from its origins, establishing a union between concept and color.

The use of lighter, darker saturated colors that follow the same monochromatic range highlights certain environmental elements. For example, the contrast of the shadows in Figure 8 (these are minor details, in addition to the psychological sense of those that bring us closer to reality). Although we know we are in a fantasy world, these colors connect us and make us believe in it. For instance, it is possible to see this state through contrast and divergent colors. According to Garau28, this combination and connection of color with divergent colors "creates a tension towards a common balance".

Although Natalie Kalmus's29 color guide was still being used, especially for developing concept art for Technicolor-related films, the same author suggested a close relationship between the use of color, the technique, and the theme for its application. It is important to remember that color is related to its intrinsic relationships and social, cultural, and symbolic connections.

This social and cultural symbolic relationship is crucial to understanding Alice's images. These elements are presented together in the transversality of color, which Hernandez30 explains as those elements that we relate and connect to color that remain natural in the reading of color through time.

The transversality of Alice allows us to draw parallels between elements of the story and human rights, which are more prominent in the 2010 Disney adaptation. This version includes clear references to Alice's loss of freedom and discrimination at the hands of the Queen of Hearts. The 1951 version, however, presents a different relationship between color and these themes. From the beginning, this version aimed to promote reconciliation and political empowerment, which is reflected in its color identity. The use of certain colors reinforces the concept of equality and demonstrates that colors previously considered unworthy are now essential to the story.

A narrative that "colors" human rights

The classic tales seem to be irresistible. They prevail from generation to generation. They are renewed and transformed, constantly becoming part of our lives, moving from an oral tradition to a written one, visual and audiovisual; playing a crucial role in people's lives, staying alive and sending a message to the present day, offering hope and change in the world at the same time . According to Zipes31, "These stories capture worlds of naive morality that can still resonate with us when the underlying dramas are recreated and reimagined to respond to and collide with our complex social realities".

Despite the changes over time, the social meaning of these stories has not changed. Although they have been updated, the chromatic messages, extracted from the visual images and reinforced over time prevail in their structure, which is related to their essence, social meaning, teachings, and morals. In After Rouge, Paul Eling states, "A fairy tale, then, is about history, about morality. And this moral is meant to be retrievable from memory in all situations."

Through their images, these stories always propose an existential problem in a concise and precise way. They allow us to confront and simplify problems in their elemental form when we are faced with complicated situations. The characters are very well-defined, and complicated details are suppressed. The characters are typical rather than unique, representing opposing sides and different ethics. This duality implies a transcendental moral problem, which, when compared to a legal background, underlies the normative intention of the Declaration of Human Rights: moral justice minimums that seek to build a just society, a world in peace and harmony, defending the integrity and qualities of each person.

In Alice, the Disney version also addresses the right to life, liberty, and equality, particularly in the chapter about Alice and the Queen of Hearts. The use of red, associated with force, violence, and danger, reinforces these themes. Disney, on the other hand, places less emphasis on these elements by using a less saturated shade of red. Inequality is also present in the difference in the size and costume of the king and queen. The king's costume is much more benevolent, with only a combination of three colors (white, red, and yellow), while the queen's costume features black and yellow, the latter of which is scarce compared to black and red. The yellow and white colors in her costume are almost decorative, emphasizing the queen's power and darkness.

In "Alice in Wonderland", the use of color can also be seen as a way to challenge social and cultural conventions. For example, the character of the Duchess is associated with the color brown, which represents modesty and unimportance, but can also be seen as a symbol of the working class and oppression (Lurie, 1974). This can be interpreted as a symbol of a stratified society, such as that of the 19th century, and thus of inequality. Similarly, the character of the Dormouse wears a yellow suit, which represents cowardice and treachery, but can also be interpreted as a critique of superficiality and vanity (Kestner, 1989).

Characters such as the Queen of Hearts, represented by the color red, the Duchess, represented by blue and brown, and the Cheshire Cat, represented by the color purple, can be interpreted as a way of establishing hierarchies and contrasts between characters and can be seen as a form of culturally established discrimination. Thus, the use of color in "Alice in Wonderland", can be interpreted as a form of cultural discrimination due to its high contrast for the theme and effect it wants to create in the narrative of the story, and, therefore should be addressed from a human rights perspective.

On the other hand, Tatar (1987) notes that the use of color in "Snow White" can also be seen as a way of establishing hierarchies and contrasts between characters. The stepmother, in her black dress, is an authoritative figure who contrasts with Snow White, in her white dress, who represents the maternal figure. This contrast is further emphasized when the stepmother, in her black dress, transforms into the witch, while Snow White is rescued by the dwarfs with their colorful outfits. From Bettelheim's perspective (1989), this relationship is presented as more naturally tied to universal concepts and experiences. Fairy tales like "Snow White" use color to establish a conventional and culturally established symbolism. For example, white is often used to represent innocence and purity, while black is used to represent evil and death. In "Snow White," the use of color is very conventional. Snow White's dress is white, representing her innocence and goodness, while the stepmother's clothing is black, representing her evil and envy. The poisoned apple is red, which can represent danger and temptation.

The use of colors in fairy tales, such as "Snow White," to establish hierarchies and contrasts between characters may reflect culturally ingrained discrimination. For example, the authoritative figure, the stepmother, is represented by a black dress, while the maternal figure, Snow White, is represented with a white dress. This use of color can be interpreted as a form of discrimination on cultural and arbitrary grounds. Human rights, in their struggle for equality and non-discrimination, seek to eliminate these cultural stereotypes and promote inclusion and equality for all individuals, regardless of their gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, among others.

On the other hand, and related to the above, the fact that black is used to represent the evil and envy of the stepmother can be seen as a form of culturally embedded discrimination against the color black and people who wear it or have darker skin. Similarly, the fact that white is used to represent the innocence and goodness of Snow White can be interpreted as a way of privileging those who are perceived as "pure" or "innocent" over those who are seen as "impure" or "evil".

Colors and Social perceptions

As Eduardo Perafán states in his various works32 33, aesthetics has a political connotation that intervenes in the sensitive frameworks of society and conditions how the series of social interactions are staged in public space. Thus, we could think that color is also part of the aesthetic resources that can be used as political tools to promote certain ideologies, values, and ideas in a group of people.

The imagery of these stories tends to pose an existential problem in a succinct way, where evil and good are omnipresent. Both are embodied in individual characters and confirmed by their behavior. This duality implies a transcendent moral problem that underlies the normative intention of our social relations as compared to a political standpoint. Allusions to freedom, equality, the problem of discrimination, and the indictment of power before the most vulnerable subjects are present in the reading of these images.

The transversality of color is used in these stories as a narrative medium for social messages. Therefore, it is possible to propose hermeneutical exercises from semiotics that show this relationship, not only by the denotative and connotative chromatic character, but also by adjusting to the context that makes the reader take them as references, to extract lessons and to apply them to their own lives.

In this order of ideas, let us examine some of these interpretations:

a-) A legal perspective of equality between equals is defined in the film, as mentioned earlier in Disney's Snow White. The presence of colors such as brown and sepia, of noticeable attenuation, are designated to secondary or subordinate characters, subjects whose job is to serve, to perform hard work. Notice that it is used in the clothes of the hunter whom the Queen orders to kill the young woman, and also in the clothing of the dwarves, who work in the mines. Even the princess wears it in a ragged dress with patches when we first see her on screen.

In the group of dwarfs, the colors bind them creating a uniform to clarify their group identity. In contrast, we know that Snow White, who belongs to the nobility, a superior social class, is portrayed in most of the film in colors that allude to this position, such as yellow, red, black, and blue. These also resemble the colors of the clothes worn by the Queen.

b) In the case of Alice, everything in the story is about liberation. From the moment she enters the White Rabbit's hole, free-thinking becomes routine, so anything is possible. Anything can happen. Making herself large and then small suggests that there is no definite place for her. She enters a game of unnecessary things. She does not fit in with her surroundings, which is related to the color of her dress.

The precise combination of blue and white creates an integral vision of the definition of the human person embodied in the girl. Blue defines multidimensional freedom, for example, locomotion (she moves to any place she wants without significant restrictions), conscience, and thought (despite the inconsistencies she faces, she says what comes to her mind). On the other hand, the white refers to neutrality in the conception of things and situations: the duty to recognize and accept differences and to accept others as they are, with their characteristics and conditions.

The blue caterpillar encounter raises the story to levels of uncertainty and the notion of unlimited freedom. The conversation challenges logic and limiting conventions and is an apology for dignity in self-definition and determination. It is no coincidence that the caterpillar is also personified in blue. The characters of the Mad Hatter or the Cheshire Cat stand out for the exaggerated chromatic variety that colors their clothing, a syncretism that alludes to the pluralism of rights, while undermining the idea of a pre-established order. Self-determination is ostensibly a legal discourse.

c-) On the other hand, there will be discrimination as far as there are monarchs, which involves classifying individuals. Queens appear in both stories; therefore, they are assigned a preponderant role, highlighted by the colors they wear and their royal costumes. Scarlet, purple and black, of historical significance, associated with the ornamental costumes of positions of power. In addition, the golden crown of both queens denotes the lack of equality before the law. A monarch himself bases his power on autocracy and emphasizes the absolutist condition of the same.

Even when Snow White's stepmother disguises herself as an older woman, she does not lose her royal status. Black takes over the entire wardrobe as a symbol of dark, intimidating power, that oppresses and damages. However, these chromatic changes were not the invention of Walt Disney.

Similar aesthetic features, linked to the cabalistic and esoteric world are found in the fantastic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, by authors such as Walpole, Radcliffe, Maturín, Poe or Lovecraft, and in turn also in film productions, both European and American as Del Arco34said.

We can appreciate that the narrative elements combining a mimetic perspective of human rights are varied. But equally, the basic plot will converge representations alluding to the violation of universal legal guarantees with the semiotic condition of the suggested colors. We propose to analyze this aspect in order to find new dimensions of influence and impact of a literary genre that has accompanied humanity for centuries in terms of intellectual, artistic, sociocultural, and now, legal transcendence.

Conclusions

By understanding the concept of color transversality and applying it to the visual imagery of classic stories, we can more easily understand its use within them, approach the type of message we want to convey through them, and facilitate the power to exercise a critical look at those types of messages.

Fairy tales or classic tales have imitated and syncretized philosophical orientations and patterns of behavior, constant themes of human evolution, and a permanent reflection of the factors of power in social life that deserve new forms of reading in contemporary times.

These stories are based on semiotic elements that go beyond the exegesis of the events proposed as the structural form of the story being told. It is possible to delve into a hermeneutic study that examines the denotative and connotative treatment of color in order to identify the construction of imaginaries produced by readers according to the context in which they are located.

In "Alice in Wonderland", and "Snow White", for example, we see the permanence of this literary genre, with constant audiovisual adaptations. The interpretive presence of general principles translated into human rights is undeniable and relatively easy to identify in various socio-cultural scenarios. These principles include allusions to freedom, equality, the problem of discrimination, the accusation of power against the most vulnerable subjects, and much more.

Consequently, it is appropriate to discover new perspectives on these narratives that have endured through time, in order to look at our reality from different angles, and to understand that there are normative values that have changed form and should be recounted but not applied."