Introduction

Pansori (sometimes spelled ‘p’ansori’, depending on the romanization system used)1 is a type of traditional dramatic art, which is thought to have appeared in Korea in the mid-eighteenth century. In 1964, the Korean Ministry of Culture designated pansori as an Intangible Cultural Asset.

Explained by some as “one-man opera” [1 p227], or “solo-singer type of story-telling” [2 p122], it is performed in its traditional form by a solo vocalist with the accompaniment of a drum (puk), alternating spoken (aniri) to sung (chang) passages to tell folktales, playing the role of the narrator and of all the characters in the story. The original repertoire of pansori consisted of 12 pieces, but only 5 of them have been passed on to contemporary performers. A pansori performance can last up to 8 hours and was originally performed predominantly outdoors, in parks or courtyards. However, pansori is currently performed mostly indoors, in concert halls or theatres [3], and new forms of performances subsequently appeared, such as new pansori (pansori created since the beginning of the twentieth century and therefore not belonging to the traditional repertoire mentioned before), changgeuk (a fully staged form of pansori, performed in theatres with different actors playing different roles, costumes, an orchestra, etc.), and other forms that will be discussed in the second section of this article.

Today, pansori is performed and appreciated not only in Korea, but also in many other countries. Scientific investigations have been dedicated to pansori, analyzing its features from different perspectives -artistic, historical, anthropological, etc. In particular, many studies have dealt with artistic and vocal issues related to pansori, unsurprisingly, because of the peculiar vocal technique adopted.

In these studies, a number of widely accepted findings about vocal training, vocal health, and vocal technique in pansori arise. Mainly: pansori has a very specific sound; it can be achieved only after years of demanding training that may result in damage to the vocal cords of the students; training is based on non-codified mimetic techniques passed on through a strong master-disciple relationship.

Although its strong traditional component is still a crucial aspect, in recent years pansori has also integrated some modern innovations, which have -to some extent- addressed important issues, such as the working circumstances of the performers and the incorporation of alternative artistic forms of pansori performances.

Despite these changes, the pedagogy of pansori has not had many significant modifications since its origin.

Furthermore, although several studies have highlighted the expressive evolution of pansori, it is mostly taken for granted that the traditional vocal requirements of pansori are still valid, despite the vocal risks. There has been very little attention given to the importance of vocal quality and health for performance beyond those traditional requirements of the pansori singers’ training.

It has been noted that the repeated production of the particular sounds of pansori is often associated with vocal damage [4-7]. However, in the commonly accepted view, this is simply necessary in order to become a pansori singer.

This view makes two assumptions: 1) these sounds are essential for the pansori performance and, therefore, the consequent vocal damage due to the training is an unavoidable requirement for a good performance; 2) pansori students and performers do not know the risks of the training or do not consider vocal health very important.

Both of these assumptions may need to be adjusted, given the recent and continuous evolutions occurring in the world of pansori.

To investigate, we decided to look at the points of view of pansori students and performers, highlighting and evaluating the opinions of those who are involved in the training, by designing and submitting to them an anonymous survey. We wanted to understand whether -and to what extent- changes in the performance and in the working circumstances of pansori have altered how performers and teachers perceive the importance of vocal health and the impact of vocal disorders in their overall life and work. We were interested in learning whether the responses in this survey would suggest a need for a change in the training of pansori.

The results of our investigation are presented and explained in the following sections of the article, supported by figures (graphs). The relevant parts of the survey and the answers collected are presented in detail in Appendix A. We are keen to note that these results -with particular regard to the two assumptions previously mentioned- are quite surprising, especially if we compare them to the commonly accepted view of this subject.

The survey was supported by an interview with a young expert teacher of pansori, who pointed out how a new view of the pedagogy and the specific features of pansori has been emerging and that this view is not always in line with the prevalent, more traditional approach.

Although the interview is transcribed in Appendix B, we decided to detail the most relevant passages in the body of the article when they are particularly useful in understanding the intrinsic evolution of pansori from the point of view of performers or in support of the results emerging from the survey.

In addition to this interview, a comparison of previous studies is also provided in order to highlight the main steps of the evolution of pansori and to hypothesize the object of our investigation. The main findings of these previous studies are tabulated in Appendix C and detailed information about changes that have been occurring in the evolution of pansori are given in the article.

Methods

The aim of this study is to investigate whether there is a need to update the training of pansori performers with special attention given to vocal health. The investigation included three different strategies.

Previous studies

Through a literature review, we analyzed the evolution of pansori, highlighting its most traditional aspects and the main changes that have occurred, pointing out how these changes might have produced a demand for innovations within the training. This preliminary analysis has also been useful in order to further specify our initial hypothesis and aim.

Many studies have analyzed pansori in its social, anthropological, historical, and musical aspects. Far fewer have analyzed the acoustics of pansori and the associated physiology involved. Only a few provided details of the pedagogy of pansori (see references). However, there is a general agreement regarding the crucial consequences of training and vocal health, i.e., that pansori would require a peculiar husky and hoarse voice quality that is obtained after years of severe training, which aims to damage the vocal cords of the students in order to obtain the required sound.

A comparative analysis of several studies enabled us to highlight some important conclusions and to form some preliminary hypotheses. Appendix C shows the main findings that we took into consideration for our work, divided into three different relevant aspects: history and evolution of pansori, training in pansori, voice quality and its acoustic and medical analysis.

Comparing these main findings, it is evident that while scholars point out a continuous evolution of pansori and its forms of performance, little evolution of its training has been noted or reported. Furthermore, many scholars agree about the frequent (and, for some, unavoidable) vocal damage among pansori singers. This led us to investigate whether the evolution of pansori has changed the perception of the importance of vocal health in the new generations of singers and teachers and, consequently, the requirements of its pedagogy.

Survey

We designed a survey in order to investigate the viewpoints of pansori singers about crucial aspects of its characteristics and training, with specific attention given to the comparison between innovations that have occurred in pansori and how it is traditionally viewed and perceived. We submitted an anonymous survey to pansori performers, using the CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interview) technique, in order to investigate their perceptions of the importance of vocal health, of the efficiency of their previous training according to their working needs, and the impact of vocal damage and fatigue on their overall life and work (which may be intrinsic to pansori and unavoidable, especially in training).

Due to the relatively small number of respondents, descriptive statistics were used to analyze and present the data. Although further and more detailed analyses are required, the study gives surprising results about a new point of view that may be an important reference for further research -a point of view that focuses on the performers’ opinions and perceptions, which is something still relatively unexplored, especially with regards to new generations.

The survey was developed by the authors of this paper in order to evaluate how performers and teachers perceive the importance of vocal health and the impact of vocal disorders in their overall life and work. Additionally, the survey investigates their beliefs about some widely accepted characteristics of pansori. It consists of 22 closed-ended questions asked in the Korean language. It was spread by word of mouth among pansori students, teachers, and performers. Data collection lasted approximately one month, and the total number of respondents was 41; all the responders answered all the questions in the survey, so there were no changes in the number of respondents during the data collection process. However, question 6 of the survey was addressed only to the responders who perform in changgeuk, either as an exclusive activity or in addition to traditional pansori (28 responders out of 41).

The survey was completed anonymously in order to preserve the privacy of the interviewees. An anonymous survey also allowed us to deal with two facts, which might have affected the quality of the responses: 1) the close master-disciple relationship and the conservative environment around pansori could represent an obstacle for the honesty of singers who would not have wanted to hurt or offend their mentors; 2) some participants might be skeptical toward foreign research, especially if dealing with potential voice damage caused by pansori traditional training and performance. The latter consideration also led us to paying particular attention to avoid an inquisitorial tone in phrasing the survey’s questions.

Computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) was chosen as the surveying technique. It presented the best choice for addressing statistical quality issues and guaranteeing the survey’s feasibility. The relatively small number of respondents allowed us to produce only descriptive statistics.

The main topics on which the survey has been designed are the following: 1) whether pansori singers perform and/or study other musical genres or new forms of performance (e.g., changgeuk); 2) beliefs about certain well-known characteristics of pansori performing and pedagogy; 3) the perception of the relationship between pansori and vocal health, and, accordingly, the importance that pansori singers assign to vocal health.

The results of the survey are presented, explained and discussed below. Appendix A shows all the questions and answers (translated for Korean to English), as well as graphs in order to facilitate reading the data.

A young teacher’s point of view

Watching live performances or listening to recent recordings of pansori, especially in its fully staged form (called changgeuk), we noticed that not all the voices heard on stage sounded breathy or hoarse. Different performers used varying degrees of hoarseness, even though many scholars pointed out that hoarseness and breathiness have always been important requirements of the voice quality used in pansori.

To gain an expert point of view about teaching pansori and the related voice production issues, we interviewed Moon SooHyun, a professional pansori performer in her late thirties, which is considered young for a pansori performer. She has won two national competitions: the Korean Traditional Music Association and the Namdo Folksong Competition. At the moment of the interview (2018), she was a teacher at Chung-Ang University (regarded as one of the top Universities in Korea offering degrees in pansori), and she was a guest instructor at TBS efm (Sounds of Korea). In addition, she was a pansori instructor at National Theater of Korea’s Traditional Performing Arts Academy for Foreigners, and occasionally leads introductory workshops for foreigners at Bukchon Traditional Culture Center (see Appendix D).

Moon SooHyun shared her perspectives from the inside of the world of pansori. Her contributions proved important for the purposes of our study [8], in part because she teaches Koreans as well as non-Koreans and she represents the younger generation of both teachers and singers. Many other studies only incorporate interviews with master singers and teachers from previous generations.

Results

Previous analyses of pansori seem to highlight the importance of hoarseness and voice disorders in order to achieve the unique tonal quality that is attained after years of demanding training. The balance between vocal health and artistry in pansori seems to be both challenging and controversial. Training in pansori is based on mimetic training and it has not changed significantly since its origins. However, through an anonymous survey submitted to 41 pansori singers, we have noticed that a new tendency is appearing. A cleaner sound is more accepted than it has been historically, and hoarseness does not seem to be an essential requirement neither for the essential expression of han (an emotion often defined as “sorrow”, that fulfills the majority of Korean artistic production) nor in considering whether a performer is good; there is much more attention paid to vocal health, as many of our interviewees are concerned about it and experience some discomfort in their life and work attributable to voice disorders.

This might be due to the ongoing evolution of pansori that now includes more western influences and new forms of performance with new accompaniments that create potential challenges for singing according with the traditional pansori style. Most of our interviewees perform in western-derived musical styles, but they would be prevented from doing so by having an unhealthy voice. Changgeuk is a very popular fully staged form of pansori that not only involves the majority of pansori singers, but it is an important part of their job, and it also contributes to the definition of the voice quality due to its popularity, and it also has technical requirements that the traditional training in pansori does not address.

As the results of the survey show, this evolution has changed the attitudes of performers towards vocal health and this might suggest a change in the way pansori performers are trained.

Discussion

A specific voice quality with unique acoustic and physiological characteristics and some vocal health issues: han in pansori

An important concept needed to understand voice production in pansori is the notion of han, which fulfills the majority of Korean artistic production in many different fields, including pansori.

When asking Koreans “what is han?”, they would likely answer that it is impossible to explain to foreigners, since it is a typical Korean emotion that includes historical memories of invasions, wars, famines, and other problems that contributed to a collective trauma and a national feeling of grief. It has been reported that han is a relatively recent idea in Korean culture, first appearing during the Japanese colonial period following the treaty of 1876 [9].

Han seems to be one of the most important expressive elements when singing intense and dramatic moments of pansori. Although it is not consistently used in all of the repertoire, it is expected that han will be expressed at some point in a pansori performance. The movie Seopyeonje and its popular musical theatre adaptation beautifully illustrate the importance of this emotion in pansori. Han is often defined as ‘sorrow’, though Moon SooHyun points out that it is rather “repressed sorrow”2 (see Appendix B).

Seongeum, the voice quality in pansori and relative importance of hoarseness: is this ‘han’ in voice?

Teaching such an undefined sentiment creates problems in pedagogy and voice technique. We asked Moon SooHyun: “how would you express han in your voice?”

This is actually the most difficult question. I’m sure that every singer has a different idea about han. I can share with you my personal thoughts, though. We use the word ‘seongeum’ to define the tone color of pansori. This is the most important thing that a pansori singer must achieve: the particular tone color. That seongeum will come to singers who have a drastic training for a long time or [have] special talent. And that color expresses han. This means that han is not a technique, but the color that the singers have, that is influenced by their life. So, if the singers have suffered or they have much repressed sorrow in their life, their voice color would be great. That’s why older generations are much more talented than younger generations, even though I think it’s not only a matter of quantity of han, but also of kind of han. New generations have a different han, they experience different kinds of sorrow. (Moon SooHyun’s personal interview, 2018; Appendix B).

Many other scholars, performers, and teachers point out that the ‘tone color’ or ‘voice quality’ is the most essential thing in pansori [10,11]. This quality is very particular and it is said that it is only attained after years of severe and demanding training. However, while most attempt to describe it from a perceptual and subjective point of view, there are very few studies on the objective acoustics and physiology of this voice quality.

Moon Seung-Jae of Ajou University conducted two valuable analyses on acoustic characteristics of pansori voice quality [4,12]. The following points summarize his conclusions:

He noticed a relatively flat spectral slope3.

Pansori singing has a uniquely identifiable vibrato, so different from the ‘western’ standard that he questions whether we should actually call it vibrato (confirmed by Hong, Kim H, and Kim S, 2006) [6].

There is a prominent partial located lower than 1kHz.

Most pansori singers’ voices sound hoarse.

Some sounds, anticipated to be periodic, like vowels, are actually aperiodic.

Some of these characteristics were present also in the speaking voice, which suggested that the source (vocal folds) had been changed permanently by an intensive training.

For the purposes of this study, points four and five are the most interesting (although we will discuss point six in the following chapter). The “aperiodicity” observed by Moon is often described by scholars as “typical husky sound”, “hoarse voice”, “rough sound”, etc. [10,11]. Others have reported high levels of jitter and shimmer in pansori voices4 [5], parameters often connected with hoarseness in voice [13]. Many also think that this hoarseness is actually han in voice. Willoughby tried to describe the musical and vocal features of han in pansori, and she concluded that among other factors, harshness has an important role in the expression of han [10]. Other studies have tried to describe the acoustic characteristics of han [14]. But is “harshness” actually aperiodicity? Is it “hoarseness”? Is it really important to have a “hoarse” voice in contemporary pansori?

Not really. It is not compulsory. I would never say that a pansori singer is bad just because he or she has a clear tone. Hoarseness comes naturally with age; nowadays, if the voice doesn’t get hoarse with age, the singer is even considered a better singer. (Moon SooHyun’s personal interview, 2018; see appendix B).

This surprising assumption seemed to contradict the common view of voice quality in pansori, so we asked the same question to our interviewees. Figure 1 and Table 1 show their answers (see also Appendix A). As noted below, hoarseness is important for only 27% of the interviewees, and not all of them use a hoarse voice on purpose.

Table 1 Use of hoarseness in performance

| (For those who assign any importance in having a hoarse voice) Do you ever sing with hoarse voice ON PURPOSE? | |

| Yes | 63.9% |

| No | 36.1% |

| TOTAL | 100.0% |

To quantify the level of hoarseness required in pansori, we asked participants to rate the ideal level of hoarseness in pansori voice on a scale of one to ten, where one is a clear tone (not hoarse at all) and ten is a tone so hoarse that it is impossible to perceive the pitch. As Figure 2 shows, some interviewees answered 1 and some others answered 10, suggesting that there is a broad range of opinions about this aspect of the voice. However, when we asked them to give the minimum and the maximum levels of hoarseness, they gave us more even values (see Appendix A).

As the answers received from the interviewees and as Moon SooHyun suggested, the features of han, as well as of pansori itself, are not necessarily connected with hoarseness. Thus, they suggest that there is neither a direct correlation between hoarseness and han, nor between hoarseness and the appreciation of a singer’s skills.

Vocal health and physiology of pansori

Why is it so important to discuss hoarseness? As previously discussed, many scholars consider it an essential part of the pansori sound. Its connection with potential vocal health issues cause concern and require consideration that cannot be ignored in a contemporary pedagogical setting.

Hoarseness has been associated with voice disorders and it is an important factor taken into consideration in the majority of systems for perceptual evaluation of dysphonia, such as GRBAS scale [15,16] and the VHI -Voice Handicap Index [17-20].

In fact, pansori singers have often been diagnosed with severe voice disorders: researchers observed nodules, asymmetrical vocal folds, and damage to the mucosa that often required treatment. In some cases, problems were so significant, even after treatment, that the voice was no longer audible. Some concluded that this was the result of a non-scientific training method, dating back to the 18th century, which has only been transmitted orally [5-7].

Moon made almost the same conclusion (see point six of the summary, above), noting that many characteristics of pansori singers’ voices were also present in their speaking voices. He hypothesized that a permanent change occurred in their voice source (larynx and vocal folds) due to intensive training. This was the result of another important observation: pansori voice seemed to be “pressed” yet “breathy”, which suggests a physical change that prevents the vocal folds from closing, so that they can produce an “aperiodic noise under pressure” [12 p23]. However, it is important to note for our study that his research was based on recordings (rather than live performance) of five eminent and aged pansori singers, including two who were no longer alive at the time.

Pedagogy of pansori - The demanding training

In 1980, university courses in pansori were introduced in South Korea. However, it is commonly acknowledged that the university can only partially provide the students with the appropriate training that they need [21]. This is due to the universities providing limited contact time for pedagogical input and, therefore, the learning and performance outcomes of the trainees. Pansori singers start their training much earlier than when they enroll in college, usually when they are age 15 or 16 at the latest [21] (see also private interview to Moon SooHyun, Appendix C)

The way pansori is often taught is through mimetic techniques, even in universities, where students record the voice of their teachers and try to repeat what they do [22]. The techniques of pansori have traditionally been transmitted through this master-disciple relationship paradigm [23].

Appendix D offers an example of how Pansori is taught today, describing a one-day workshop that we observed in May 2018. Although this was a workshop for foreigners at the amateur level that was taught in English over the course of only one day, it still shows the general characteristics of the pedagogy of pansori and its training methodology (such as call-response and other mimetic techniques, attention given to different embellishments, etc.).

In the training of pansori, little attention is given to voice technique; most of the training is focused on artistic aspects, such as different “modes” (jo, scale or style) [24] or different embellishments. In fact, in pansori the word “voice technique” is often synonymous with “embellishment” rather than technical voice production [3]. Technical work is mostly focused on breathing, which is considered to be responsible for a powerful and loud sound [7], despite recent research indicating that breath is only partially responsible for the intensity of voice [25].

Part of the traditional training of pansori used to occur in the mountains, or in a natural environment, over 100 days. The legend says that students used to train their voices surrounded by waterfalls in order to develop loud sounds that could be heard over the noise of the water. Pihl described it like “a period of deprivation, of exhausting efforts to acquire ‘a voice’”, reporting that during this training, singers often spat blood from their mouths [23 p51].

Contemporary students still follow this tradition, but with less intensive training over a shorter time period: one week at the shortest, one month at the longest [2] (see also private interview to Moon SooHyun, Appendix B).

In spite of these historical reports, the vast majority of our interviewees (almost 71%) say that their training was not focused on producing a hoarse voice (Appendix A).

Is vocal health a real issue?

Some say that these voice disorders should not only be accepted, but encouraged by pansori singers [2,22,23]. The Western training is now more focused on preserving the vocal health of the students, so we might find this encouragement of disordered usage absurd.

However, the balance between the artistry of a sound and the vocal health of the singer is something that in this case can be very delicate. Only some have reported these voice disorders as a negative consequence of excessive vocal effort; others seem to agree that pansori singers have certain voice disorders that contribute to the unique aesthetic of the voice quality required by the genre [2,4,10-12,23].

Korean newspapers have reported on doctors making claims about singers losing their careers after surgery for voice disorders, or about singers who decided not to receive treatments for dysphonia even though their voices were becoming increasingly pathological.5

However, this idea may be changing, given that Table 2 reveals how important our interviewees consider vocal health for pansori singers.

Table 2 Importance of monitoring vocal health in pansori/changgeuk

| How much do you think it is important to monitor vocal health and to keep the voice healthy for those who had an excellent artistic training in Pansori/Changgeuk? | |

| Very important | 92.7% |

| Quite important | 7.3% |

| Not very important | 0.0% |

| Irrelevant | 0.0% |

| TOTAL | 100.0% |

Is this the result of an increased level of attention to vocal health in general within the field of the performing arts? Is pansori evolving so much that hoarseness has become less important? Has the traditional role and the job of a pansori singer changed to include other styles of performances of musical genres? Singers today consider vocal health more important than singers from two or three hundred years ago, who used to sing outdoors in a traditional performance context accompanied by only a drum. Does this indicate that the pedagogy of pansori has changed according to these new views? We will answer these questions in the next sections of this article.

Evolution of Pansori

“‘Traditional pansori’ was designated as an Intangible Cultural Asset by the Korean Ministry of Culture in 1964 and was also proclaimed one of the UNESCO Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2003” [26 p26]. Even though it might seem that these attempts to preserve pansori are the expression of a generally conservative attitude, the reason why they occurred is that the evolution of pansori risked going too far.

Many scholars observed numerous changes in pansori due to its “encounter with modernity”. Some reported an evolution of the genre that elicits contrasting reactions from traditionalists and innovators [26]. Despite the contrasting reactions, the dialectic between innovation and conservation in pansori is clearly present.

The purpose of this study is not to take a position in this dialectic, saying whether the evolution of pansori is something to encourage or counteract. Our purpose is to report these changes and to see if they suggest that some adjustments in pansori technique and its pedagogy may be allowed as part of modern performance practice.

New venues and new audiences

One of the biggest changes that has occurred in pansori since its origin is in the venues where it is performed.

Originally performed outdoors, it was supposed to be heard “amidst the loud hurried crowds of the market-place” [22 p298]. More recently, pansori is performed in theatres or concert halls, sometimes even amplified by a microphone. As Yeonok Jang analyzed [3], this change had a huge impact on the response of the audiences during the performances and consequently on the performers’ attitude and on the performances themselves.

Therefore, the intensity originally required in pansori may now be considered optional, belonging more to the realm of art and style rather than that of an essential technical requirement of pansori.

New styles, new forms of performances, new perspectives, internationality of pansori

Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, pansori has undergone an evolution that has produced new forms of performance that coexist with more traditional styles and performances.

New accompaniments

In 1987, the first pansori performance with the accompaniment of a western ensemble took place. After that, even some of the oldest and most popular performers participated in various kinds of pansori performances accompanied by a western ensemble (although these performances are still relatively rare among traditional singers).

The most important consequence of these new accompaniments (for our purposes) is the lack of freedom in choosing the key of the song, in addition to the impact on the perception of tempo and management of speed. When only a drum accompanies the singer (as in the traditional form of pansori performance), the drummer adjusts his speed to that of the singer, and no melodic or harmonic references limit the choice of key. The singers are able to choose the most comfortable key and are free to adjust it according to their vocal condition or tiredness relative to their sensations and feelings [3].

New pansori

The original repertoire of pansori consisted of 12 pieces, but only five of them have been passed on to contemporary performers. They coincide with the five cardinal principles of Confucian ethics.

As Hae Kyung Um reported [26], in 1904 the very first piece of “new pansori” appeared. The term “new pansori” refers to pansori created since the beginning of the twentieth century and therefore does not belong to the original repertory (the five pieces). These new pieces and songs are compositions that are arranged, improvised, and performed according to the conventional musical styles, techniques, rhythms, and modes of traditional pansori. There are, however, new influences in text, music, performance style, and also production and consumption of performances. For example, they emphasize humor in contrast to the han of previous pieces, and they introduce a new language much closer to contemporary colloquial Korean, using a wider variety of regional accents. Many elements of popular culture (including Western culture) are added to these new performances.

These changes (less han and more humor, contemporary language, different dialects, Western influence, etc.) affect and modify the voice quality used in new pansori, and gives rise to controversies.

Although new pansori is gaining popularity among young audiences, more conservative people have voiced strong criticism. In spite of this, new pansori performers proudly claim that they are regaining the original spirit of pansori “as living art”, rallying against the fossilization of the art form following the 1964 declaration of pansori as a “national intangible cultural asset”. This statement is present in a declaration made on February 13, 2004, by a group of new pansori performers that call themselves National League of Ttorang Kwangdae. It is essential to explain the meaning of the word kwangdae, the relevance of this declaration and even of the name of the League itself:

Kwangdae and Ttorang Kwangdae. The word kwangdae refers to the professional pansori performers that have received their training and the acquisition of the repertoire and style from one of the major pansori schools or “proper” lineage of style. Ttorang kwangdae, instead, are those singers that do not belong to any of these schools and the word ttorang is generally used in a pejorative way to label those who are not likely to be able to attain the status of a “proper” performer. Ttorang kwangdae have not attained the seongeum, the sound or unique voice quality of pansori that is usually acquired after years of demanding vocal training. It is important to note that the artists of the League proudly used the term ttorang Kwangdae to define themselves and declare their intent to make pansori “regain a new life”, implicitly undermining the importance of the seongeum, and even highlighting the lack of this sound as a positive feature. The debate around new pansori is not only artistic, but political, cultural, and social. As a team of researchers, we have neither the right nor the knowledge to take part in this debate or align ourselves with one side or the other, but we are interested in reporting these changes that affect all forms of pansori. As Hae-Kyung Um observed in 2008:

It is perhaps too soon to predict where all these creative energies will lead. But one thing we could deduce from the dynamics of pansori development in modernity is that tradition and creativity are not only compatible with each other but inspire and give new life to artistic expression [26 p48].

In other words, it is likely that the importance of new pansori might have affected the form of performances of traditional pansori itself, especially in terms of voice quality, contributing to stimulate a continuous change of the preferences of the audience that is unavoidable and contribute to a certain evolution of every musical style.

Changgeuk

Korea didn’t have theatres until the beginning of the 20th century, more than a hundred years after the appearance of the first forms of pansori. For this reason, the role that was played by indigenous narrative theatrical forms in other Asian countries, such as Peking Opera in China or No, Joruri or Kabuki Theatre in Japan, was played by pansori in Korea.

However, when in the early 1900s the first theatre opened in Korea, a stage form of pansori, where different actors performed different roles, appeared. Gradually, costumes and sets were added, and this fully staged form of pansori became an independent genre where the singing style used by the performers is still pansori, even though the form of performance is considerably different from the traditional. The name of this new style is Changgeuk, and its popularity has been steadily increasing. Some consider it a “popular” form of pansori, as it attracts a big (and often younger) audience; most of the changgeuk are performed with English subtitles, indicating that the interest of non-Koreans in this form of performing art is increasingly important.

In changgeuk, unlike traditional pansori performances, a singer plays only one role. There are ensembles and choirs and the show is accompanied not only by a drum but by a whole orchestra. Even though it is usually comprised of traditional Korean instruments, it occasionally includes those from west.

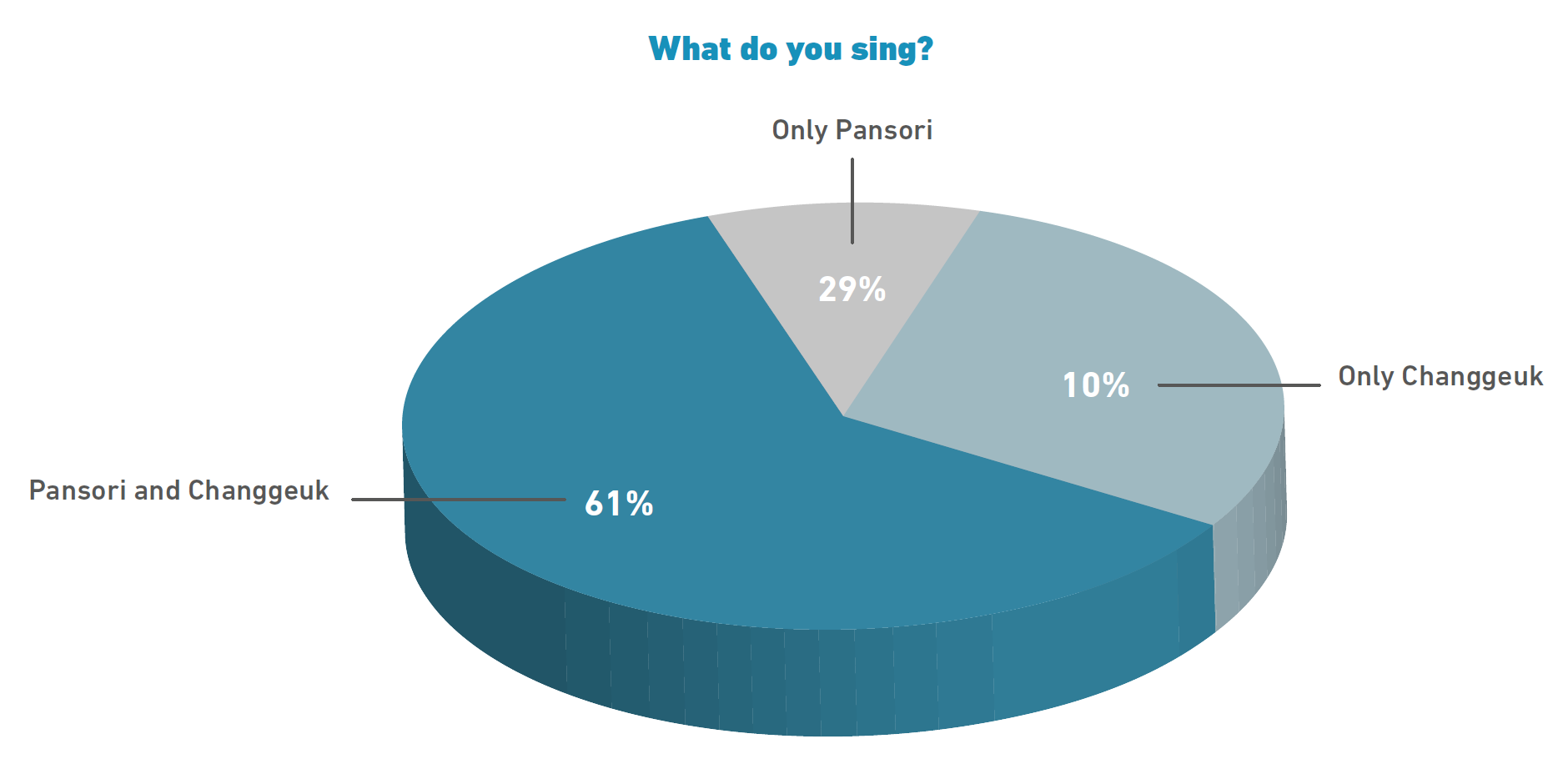

Due to its popularity, changgeuk attracts many pansori performers, and it is an important (and lucrative) part of their job. As Appendix A and Figure 3 show, only one third of our interviewees perform exclusively pansori, while the majority of them perform in both genres. Only a small group of them perform exclusively in changgeuk.

As Moon SooHyun highlighted during her interview, “Western culture affected changgeuk very much”, due to the fact that theatres in Korea are a consequence of the Western influence of the twentieth century [27], “especially in the acoustic system” (Appendix B); this is a crucial observation for our purposes of the analysis of the management of voice, because the traditional training of pansori is the only training that Changgeuk performers receive and it does not take into consideration a (relatively) new and western influenced type of performance. We will analyze this aspect in detail below.

Andrew P. Killick, senior lecturer in Ethnomusicology at University of Sheffield (UK), is one of the most published western scholars of changgeuk, and in his publications he highlights many interesting points about this form of art, that are relevant to our study: Killick explained that changgeuk is “traditionesque”, rather than ‘traditional’ and defines the distinction as follows:

These ‘traditionesque’ practices base their appeal in large part on association with tradition, but (perhaps because of their dubious credentials for traditional status according to local criteria) are not protected from change [11 p56].

Changgeuk and challenges for performers. We asked Moon SooHyun to explain the differences between the voice quality required in traditional pansori and those used in changgeuk:

There are many styles of changgeuk, because changgeuk had a big development since its origins. (…) Generally, I would say that changgeuk should be more simple, clearer, so that people can understand it more easily (Moon SooHyun’s personal interview, 2018).

Although changgeuk has its own individuality, it is a very popular form of art that is continuously changing, and it represents a major aspect of the job for many performers, who do not have a specific training in singing changgeuk, since the singing style used in changgeuk is still pansori.

But in his book, In search of Korean Traditional Opera [28], Killick highlights the technical problems that pansori singers encounter when they move to changgeuk:

The typical husky voice quality used in pansori “does not project well through a texture of other pitched sounds, particularly in large venues” [28 p197]. Microphones are largely used in changgeuk, but the orchestra is amplified as well, and the use of microphones present aesthetic problems that, according to some, affect the artistry of changgeuk.

To combine different pitched voices is hard using a pansori voice quality, and there might be challenges in intonation and coordination. Voices in changgeuk are not divided in sopranos, altos, tenors, etc., like in western music, and choirs sing in unison. This problem is yet more prominent when male and female voices are combined.6

Pitched Korean traditional instruments can play comfortably only in a few keys, reducing the possibilities of adjustment necessary to facilitate vocal comfort, which is guaranteed in pansori performances where the singers are accompanied only by a drum and can choose their most comfortable pitch, even adjusting it during a song.

We asked the interviewees who sing in changgeuk (28 responders out of 41) whether they find the control of their voice easier or harder than in pansori. In Table 3 you can see their answers.

Table 3 Difficulties in voice control for changgeuk singers

| (Only for those who sing Changgeuk) Considering than Changgeuk, unlike Pansori, is performed with an orchestra and choirs and then the performer needs to sing on tune without choosing his most comfortable pitch, when you sing Changgeuk, how do you judge your ability to manage and master your voice (your technique)? | |

| Very good | 20,70% |

| Pretty good | 51,70% |

| Pretty bad | 27,60% |

| TOTAL | 100,00% |

Importance of changgeuk in pedagogy of pansori

In conclusion, due to its popularity and ability to develop and renew itself, changgeuk makes significant contributions to the definition of the pansori sound among the new generations of audiences. It also represents an important aspect of the job of several pansori performers. The traditional pansori training may not sufficiently address the performance demands expected of singers in changeeuk and those it may make in the future as the art form continues to change and evolve, moving it further away from the traditional requirements of pansori.

Pansori internationally

Changgeuk and new pansori are not the only two examples of western influences in pansori.

Hae-Kyung Um reports that transnational forms of pansori or pansori-derived genres have been appearing [26]. He mentions the forms developed in China and the former USSR due to the Korean diaspora, but also a form of pansori created in English for non-Korean speaking American audiences by Park Chan E., and a pansori version in Japanese.

As Moon SooHyun’s workshops and courses for non-Koreans prove, there is an increasing interest from Westerners in pansori.

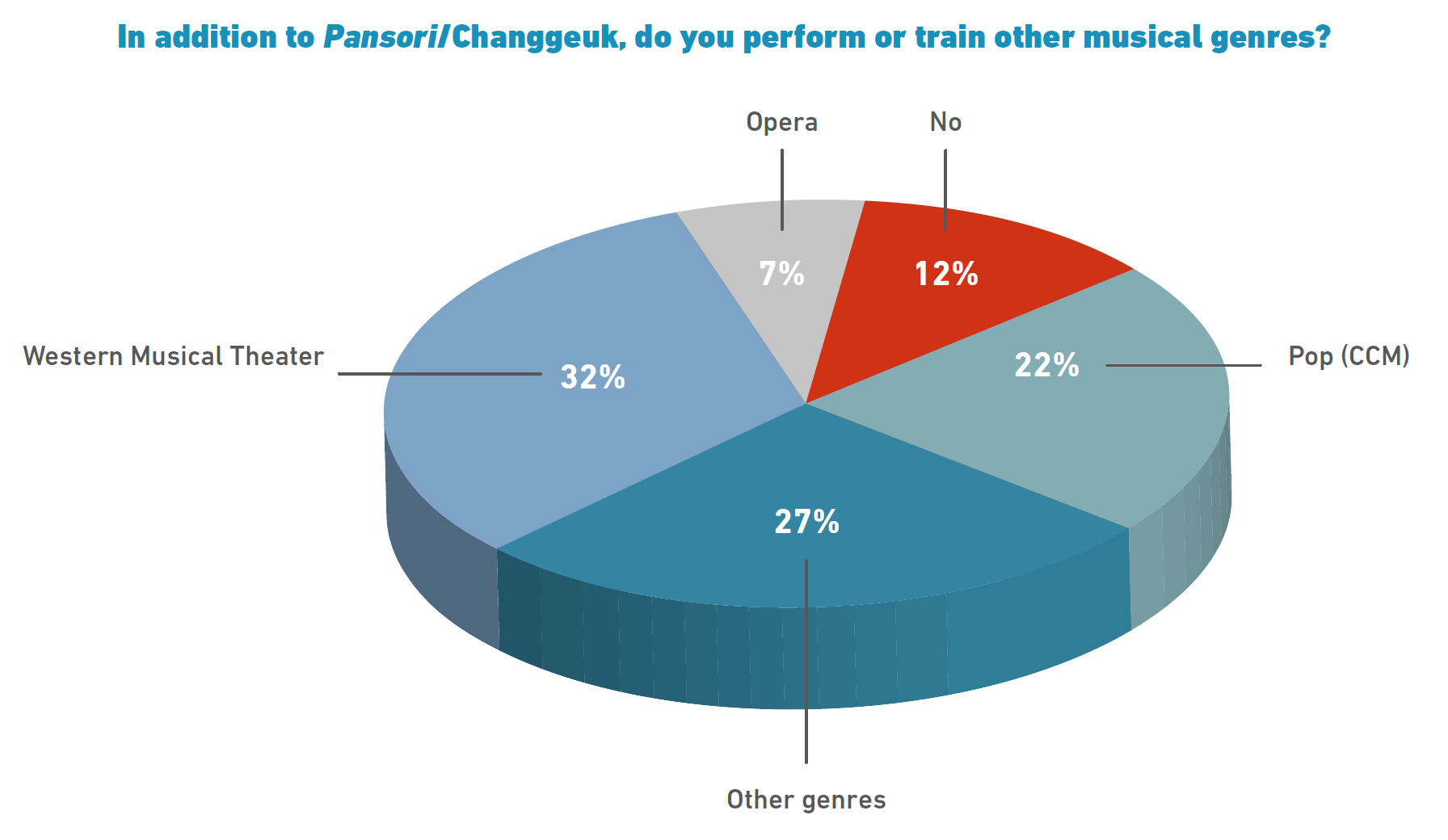

While there are many westerners that are interested in pansori, we must report that pansori or changgeuk performers do not perform exclusively in these two genres. Figure 4 shows that the majority of our interviewees perform in other musical styles, and in almost two thirds of cases they specifically indicated that they perform genres that are derived from the West, such as opera, Contemporary Commercial Music (CCM) and Western Musical Theatre.

As many pansori performers are no longer exclusively performing in traditional Korean music, the demanding training in pansori, that aims to allow the singer to attain the unique hoarse voice required in pansori, might actually represent a problem when they perform other styles that require a cleaner tone and a different management of voice.

Perception of vocal health of contemporary pansori singers and impact of voice disorders in their life

This unavoidable evolution of pansori (either in its aesthetics or in its working circumstances) is likely to be one of the reasons why vocal health is considered increasingly important among contemporary pansori singers (see Table 2).

In fact, almost all of our interviewees have experienced some kind of concern for their vocal health in their life, as Figure 5 shows.

Therefore, unlike Korean newspapers and different commenters traditionally report, vocal health does not seem to be an irrelevant issue among pansori singers.

In order to understand whether these concerns were motivated by some actual vocal discomfort, we used part of VHI (Voice Handicap Index)7 in our survey [17,20] Our purpose was not a medical diagnosis, but a way to monitor the perception that the singers have of their own vocal health. We also asked our interviewees whether their symptoms tended to worsen after performing and if they experienced fatigue at the end of performances or in intense periods of work. In order to avoid any kind of bias and derogatory meaning of the word “symptoms”, we decided to use the word “phenomenon”. Tables 4, 5 and 6 show the answers of our interviewees:

Table 4 Perception of vocal health by pansori singers according with VHI

| Do you ever experience this phenomenon in your life? | Always | Almost always | Almost never | Never |

| I feel breathless when talking | 0.0% | 2.4% | 61.0% | 36.6% |

| My voice seems hissy or dry | 0.0% | 9.8% | 61.0% | 29.3% |

| My voice sounds hoarse | 9.8% | 22.0% | 58.5% | 9.8% |

| I make a lot of effort to speak | 2.4% | 14.6% | 58.5% | 24.4% |

| The clarity of my voice is unpredictable | 0.0% | 19.5% | 53.7% | 26.8% |

| I try to change my voice in order to sound different | 7.3% | 34.1% | 51.2% | 7.3% |

| I struggle to produce voice | 0.0% | 17.1% | 48.8% | 34.1% |

| My voice is worse at the end of the day | 2.4% | 12.2% | 43.9% | 41.5% |

| My voice fails in the middle of a conversation | 0.0% | 17.1% | 24.4% | 58.5% |

| MEAN | 2.4% | 16.5% | 51.2% | 29.8% |

Table 5 Impact of intense work on vocal discomfort

| In periods of more intense performances and work, AFTER SOME PERFORMANCES, do you notice that these phenomena increase? | |

| Not at all | 19.5% |

| Yes, a bit | 70.7% |

| Yes, very much | 9.8% |

| TOTAL | 100% |

Table 6 Impact of the performance on vocal tiredness

| When you perform, AT THE END OF THE PERFORMANCE, your voice is: | |

| Like at the beginning of the performance | 31.7% |

| A bit tired | 48.8% |

| Very tired | 19.5% |

| TOTAL | 100% |

But what is the actual impact of these phenomena on their work? Some of our interviewees experienced troubles in their work due to vocal issues. Table 7 show the overall impact of voice disorders on work of the singers.

Table 7 Impact of voice disorders on work

| Has it ever happened that you had to interrupt a tour or a season or reject jobs because of lack of voice (except the normal cases of a flu or a cold)? | |

| Never | 85.4% |

| Sometimes | 14.6% |

| Often | 0.0% |

| TOTAL | 100% |

More precise statistical measurements are required, but it would be interesting to compare these data with performers in other musical genres. Having no comparative data, we want to suspend judgment and instead report our observations.

Conclusions

Further studies and more detailed research on larger groups are required, but a new approach to singing pansori is arising, as many pansori singers nowadays do not perform solely pansori. This is contributing to spread a bigger attention to vocal health among pansori singers, and despite the attempts to protect pansori from its evolution and changes, preferences of pansori listeners and audiences have been changing. These facts cannot be ignored and offer new thoughts on pansori pedagogy. Unlike previously thought, perhaps a more scientific and health-conscious approach to pansori voice training will be something from which many pansori singers can benefit, as many of them perform in western-derived musical styles, but would be prevented from doing so by having an unhealthy voice. Changgeuk is also an important part of their job, and it also contributes to the definition of the voice quality due to its popularity, although it has technical requirements that the traditional training in pansori does not address. All these facts are contributing to an increase in the awareness of pansori singers regarding vocal health.

By analyzing the unavoidable and intrinsic evolution of a traditional dramatic art that tends to be protected from change by many conservative traditionalists and describing the impact that this evolution has had on the requirements for a more effective training, appropriate for contemporary performers, our work can be situated in a more general context that reflects the need for continuous changes in voice pedagogy in response to the evolution of musical genres.