Emotions are psychological processes that encompass changes in subjective experience, observable behaviours, and autonomic-neuroendocrine physiology. Their impact can be either advantageous or detrimental, depending on the context in which they develop. Given this, the acquisition of appropriate regulatory mechanisms becomes crucial, including strategies to moderate, sustain, amplify, or modify their expression in accordance with personal objectives and specific conditions within the physical and social environment (Gross, 2015, 2024).

Emotional regulation can take the form of cognitive reappraisal, involving various emotional response possibilities, or the suppression of expression (Aldao, 2013; Aldao & Plate, 2018). It can be asserted that individuals who attain proficiency in employing cognitive reappraisal strategies regulate their emotions more effectively in alignment with their objectives and context (Seligowski & Orcutt, 2015). These individuals exhibit high levels of socio-emotional functioning and adapt better to challenging events, resulting in improved indicators of physical and mental well-being (Appleton & Kubzansky, 2014).

Many of the differences reported in the success or failure of emotional regulation (ER) among individuals are associated with factors such as the frequency of implementation, overreliance on a single strategy, the way strategies are combined, and the perception of excessive or insufficient self-efficacy. However, the clear-cut categorisation of individuals who favour one strategy over another, does not inherently align with a single adaptive behaviour a priori. It seems that effective emotional regulation requires individuals to possess substantial flexibility to adjust their choice of strategies based on environmental demands, individual personality, and cultural context. The exploration and understanding of this emotional flexibility have become significant research topics (Gross, 2015, 2024).

Due to the contemporary challenges and the inequities in health and well-being, some people manifest difficulties in regulating their emotions in the face of daily events (Rofey et al., 2013). This event invites us to think about, for example, the importance of the generation of plans, programmes and projects associated with the increase in ER as a facilitator of the sustained execution of adaptive behaviours, as well as the reduction of situations that may be related to hostility, associated with violence in all its manifestations (Gross, 2015, 2024; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2015), the management of emotional eating underlying eating disorders (Giuliani & Berkman, 2015), the treatment of borderline personality disorder (Carpenter & Trull 2013), headaches (Laguna & Magan, 2015), somatoform disorders (Berking & Wupperman, 2012), the approach to pathologies such as generalised and specific anxiety, depression and drug use (Sloan et al., 2017), and the effects on mental health, especially in young people (Martins-Barroso et al., 2023). There is evidence that we need to deepen the analysis of the implications of personality traits on the difficulties in emotional regulation experienced by young adults (del Valle et al., 2020), as well as in adults with greater symptoms of depression when experiencing difficulties in emotional regulation when exposed to a divorce situation (Garrido-Rojas et al., 2020)

On the other hand, it’s worth emphasizing the importance of developing greater competence in ER during the course of the life cycle, as it enables individuals to attain high levels of socio-emotional functioning, which could be related to other psychological potentials such as empathy and improved stress management (Hu et al., 2014); For their part, Curhan et al. (2014) propose a reevaluation of the inappropriate and negative connotations often linked to negative affect, since it would not necessarily report a significant influence on the development of mental illness symptoms in all individuals (Luong et al., 2016), and even emotional suppression is not necessarily related to negative emotions (Hu et al., 2014).

Colombia is a country undergoing a transition from a belligerent state to a post-agreement stage, linked to an armed conflict that has had far-reaching effects on the ER of its population. Many individuals, often involuntarily, have experienced violence, including massacres, torture, disappearances, forced displacement, sexual and political violence (Barreto-Galeano et al., 2022; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2015). Additionally, there are people in large and medium-sized Colombian cities who, though not directly exposed to the atrocities of war, still exhibit behavioural adaptation issues, family disruptions, school-related problems, relationship conflicts, and marital or family violence. Underlying these issues are potential difficulties in ER, creating a detrimental and persistent cycle that contributes to the development and maintenance of mental health problems. In this context, it is essential to promote initiatives at all levels that contribute to the proper identification of ER issues, including the validation of internationally recognised assessment tools for this purpose.

Regarding the measurement of emotional regulation, Pérez-Sánchez et al. (2020) find that the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) is one of the most used instruments to evaluate this construct and that the re liability expressed in internal consistency coefficients can be positively valued. Several studies in Latin America show interest in the psychometric analysis of the ERQ (Braule-Pinto et al., 2021; Gargurevich & Matos, 2010; Moreta-Herrera et al., 2018; Valencia & De la Rosa-Gómez, 2022; Vizioli & Pagano, 2022). According to the reviewed Colombian literature, it was found that, except for the efforts of Muñoz-Martínez et al. (2016), in measuring emotional dysregulation with the DERS and the processes for evaluating the psychometric properties of the ERQ carried out by Alfonso and Prieto (2021), which did not adjust to the original version, and the exploratory study by Canales-Ramírez (2020), no research has been carried out that vindicates the usefulness of the ERQ for the measurement of ER in the Colombian population, and that exhaustively evaluates its factorial structure.

To this extent, it is hypothesised that the development of a review process for the psychometric properties (incorporating factorial invariance analysis) of the ERQ instrument (Gross & John, 2003), recognised worldwide, and validated in Spanish by Cabello et al. (2013), can be useful to discriminate the two most common ER strategies, specifically in the Colombian population, recognising the linguistic and cultural distinctions that characterise this county’s population (Hervás & Jódar, 2008).

Method

Participants

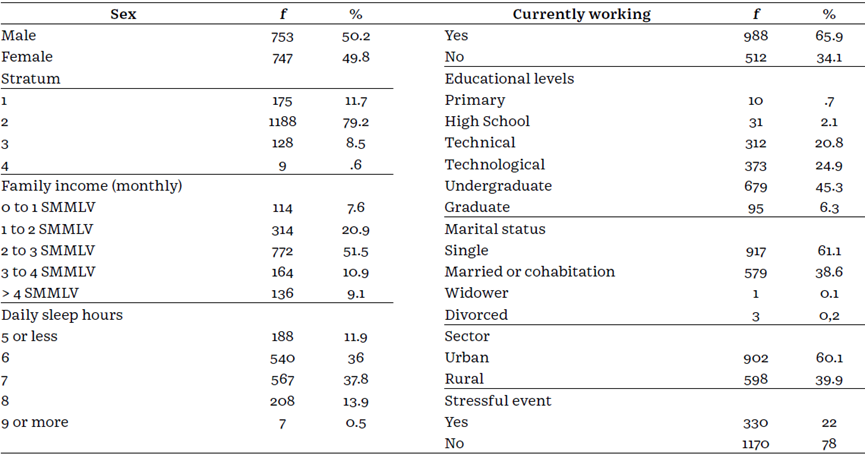

The sample consisted of 1,500 people, over 18 years of age, of all ages (X = 32.98, SD = 12.007) with reading-writing skills, chosen at convenience, from various Colombian municipalities (see Table 1).

Table 1 Sample description

Note: SMMLV (salario mínimo mensual legal vigente) meaning Current Minimum Legal Monthly Salary.

Exclusion criteria for this study included minors, individuals who had experienced a stressful event within the last three months, consumers of psychoactive drugs, and those who explicitly declined to participate.

Instruments

The Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), originally developed by Gross and John in 2003 and later translated into Spanish by Cabello et al. in 2013, assesses two common emotional regulation strategies: (a) cognitive reappraisal, consisting of six items, and (b) expressive suppression, measured with four questions. This instrument comprises a total of ten items, and respondents provide their answers on a Likert-type scale, where 1 corresponds to “strongly disagree,” and 7 represents “fully agree.” Additionally, the questions incorporate elements that estimate the regulation of negative emotions, specifically focusing on anger and sadness (Cabello et al., 2013). Both the original North American version and the Spanish translation are freely accessible.

The Flexible Regulation and Emotion Expression Scale (FREE Scale) was developed by Burton and Bonanno (2016). It is a self-report instrument that that explores how individuals apply ER strategies in their daily lives. This scale comprises 16 items with six response options in a Likert-type format. It evaluates four fac tors: F1, increase in positive expression (Alpha a = .77); F2, increase in negative expression (Alpha a = .65); F3, suppression of positive expression (a = .66); and F4, suppression of negative expression (Alpha a = .68). These coefficients are reported in the original study. An initial examination of its psychometric properties in Colombia indicated an a = .76 for Factor 1, a = .72 for Factor 2, a = .74 for Factor 3, and a = .71 for Factor 4 (Gómez-Acosta, 2022).

In addition to these scales, a sociodemographic data sheet was administered, gathering information on variables such as age, gender, daily sleep duration, socioeconomic status, educational level attained, occupation, marital status, place of residence (rural or urban), and recent experience of unmanageable stressful events within the past month.

Procedure

We used a snowball strategy, disseminated through social networks, to recruit participants. The survey contained an invitation to participate, an informed consent form detailing all relevant regulatory considerations, and the necessary instruments (the ERQ, FREE Scale, and sociodemographic questionnaire). Participants completed the online form, and we ensured that all items were answered. We thanked them and provided feedback to those who expressly requested it via email.

This study fully complies with the requirements outlined by both the American Psychological Association in its stated ethical codes and standards (2017) (sections 4, 8 and 9), and in article 2 (sections 5, 6 and 8) of Law 1090 of 2006, which refers to the professional practice of psychologists. It also adheres to the principles of data protection as mandated by Law 1581 of 2012, which ensures privacy, anonymity, and complete transparency regarding the study’s objectives for all participants. It’s important to note that the execution of this project did not involve any invasive actions that would compromise the physical, mental, or moral integrity of the participants.

Data analysis

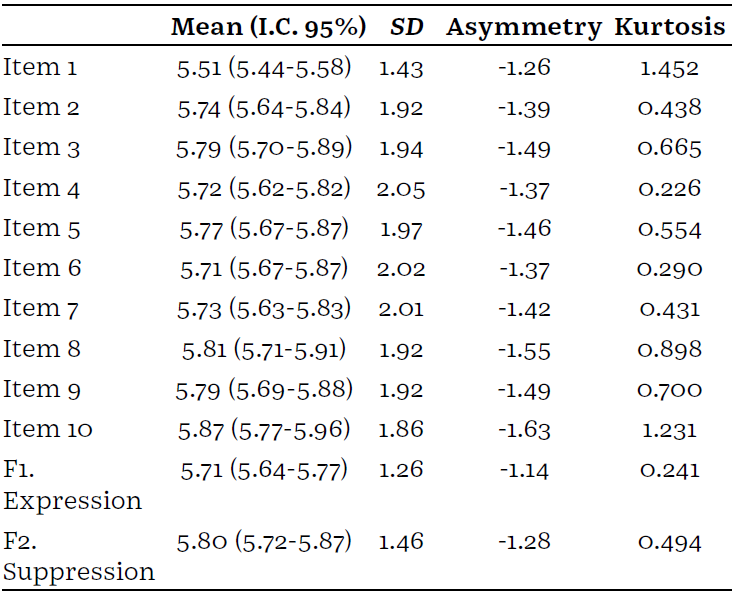

We initiated the analysis by examining each item, considering its mean, standard deviation, asymmetry, and kurtosis. Furthermore, we conducted a Kolmogorov-Smirnov analysis to assess whether the variable followed a parametric distribution, as well as a comparative analysis to determine if there were any statistical differences in scores based on sample characteristics. This analysis included the student’s t test and one factor ANOVA.

Following this initial phase, an exploratory factorial analysis was carried out under the assumptions of the Classical Test Theory (CTT) with half the sample (750 participants, drawn from the final sample). The sample was initially described using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient, to then project a factorial analysis with extraction of principal component analysis, and Oblimin rotation, with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 26 ® software.

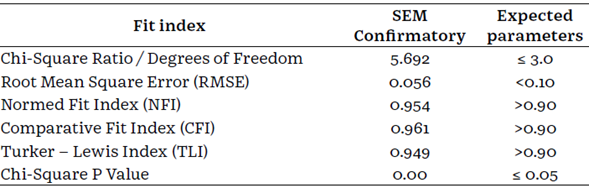

The second half of the sample was used to perform a confirmatory structural equation model (SEM), ensuring that goodness-of-fit indices conformed to the standards established by Escobedo et al. (2016) for this type of analysis. These standards included the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Normed Fit Index (NFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), with indicators exceeding .90, and an approximation Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of less than .08.

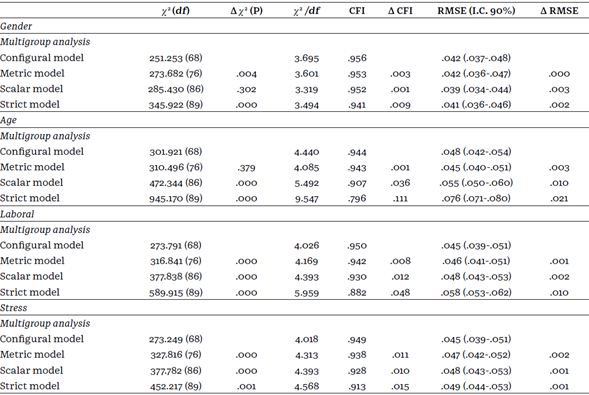

In addition, we conducted a configural invariance analysis based on gender and origin (rural or urban) following Chen’s (2007) criteria, with a ΔCFI less than or equal to .01 as well as Brown’s (2015) criteria, using the AMOS® application. To assess convergent validity, Spearman’s Rho was applied. Reliability indices were established, and internal consistency was evaluated through item-test correlations, Macdonald’s w, Gutmann’s l2, and Cronbach’s a, using JASP® software.

Result

The evaluated sample exhibited moderate to high scores in the two dimensions of the ERQ, as well as the four analogous dimensions of the FREE Scale. Notably, the distribution of items displayed a platykurtic distribution with negative asymmetry, as presented on Table 2.

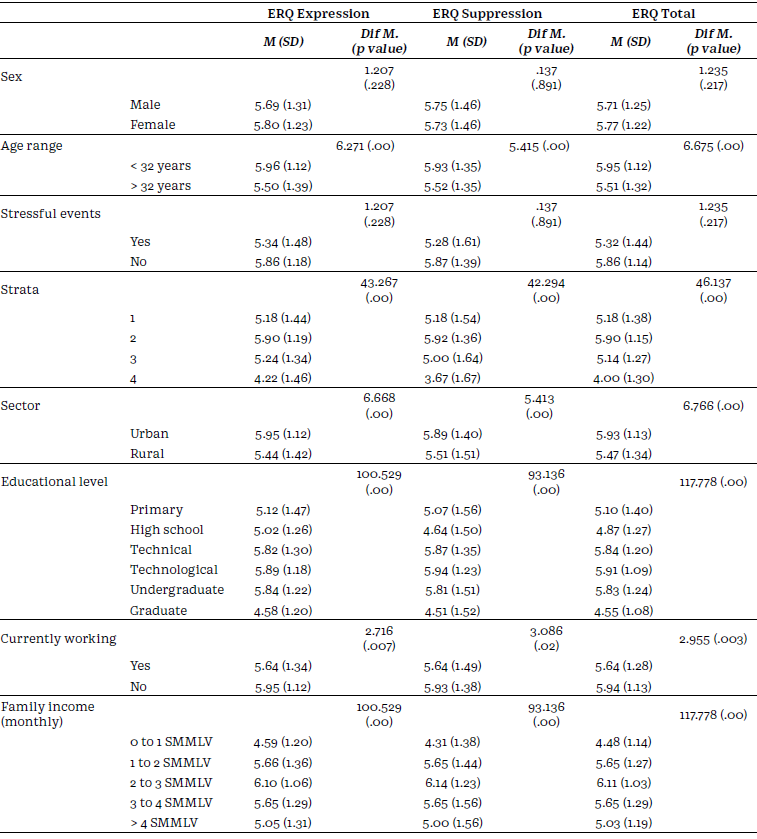

The comparative analysis according to the sociodemographic variables shown on Table 3 reports that significant differences are identified in all the criteria except gender.

The Bartlett test of sphericity (Chi-squared = 4157.897) indicated a significance level of less than .05 (Sig.) and a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index of .91. These results confirm the adequacy of the sample and establish that the correlation matrix is suitable for factor analysis. Furthermore, the exploratory factor analysis revealed that the entire test explained 55.72% of the construct variance, with 31.46% attributed to the first factor and 24.26% to the second.

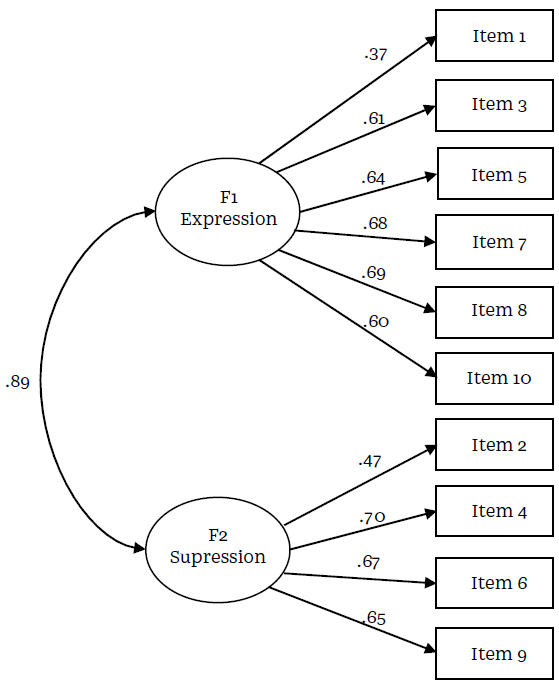

In the confirmatory analysis using SEM, it was evident that each item demonstrated factor loadings exceeding .30 in every ERQ dimension (as per Kline, 2016), indicating that differences lie within the categories measured by each factor. These findings are presented in Figure 1.

Additionally, the SEM goodness-of-fit indicators, as presented on Table 4, demonstrate an optimal alignment with the parameters prescribed for this analysis technique.

To confirm the presence of multigroup factorial invariance in the instrument, the corresponding analysis is presented on Table 6. No structural differences were identified based on the participants’ gender, as indicated by a non-significant p-value (>.05), ΔCFI of less than .01, and ΔRMSE less than .015. Overall, satisfactory fit indices were documented, except for strict invariance, where restrictions were applied to factor loadings, intercepts, and residuals. Additionally, the instrument displays a tendency to exhibit invariance across age and employment status, as shown on Table 5.

Table 5 Factorial invariance test by gender, current employment, and recent stressful events using multigroup CFA

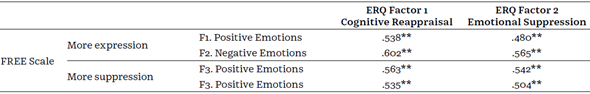

The convergent validity analysis reports positive and significant correlations with the ERQ scores, without implying collinearity and demonstrating consistency with the expected indicators (Table 6).

The analysis of convergent validity reveals positive and significant correlations with ERQ scores, with no indication of collinearity. These findings are consistent with the expected indicators (Table 6).

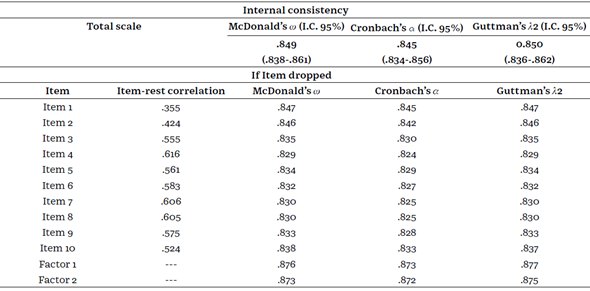

Regarding the internal consistency of the test, it is observed that the exhibit correlations with the rest of the test greater than .40 (except for item 1), and that the internal consistency values of the complete scale, the factors and of each item if the element is deleted are adequate with the three implemented statistics (Table 7).

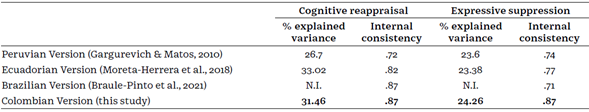

Finally, in the reassessment subscale as well as in the suppression subscale, the Colombian version shows similar indicators compared to the Brazilian, Ecuadorian, and Peruvian versions of the ERQ (Table 8).

Discussion

The objective of this research was to establish the psychometric properties of the ERQ in the Colombian population, with a significant sample of adults with diverse occupational backgrounds, from various regions across the country. The results obtained, in terms of validity, factorial invariance, and internal consistency, are adequate when compared to similar studies conducted with adults in Latin America.

The psychometric analysis supporting this assertion shows that the ERQ exhibits suitable adjustment indicators, in line with the original factorial structure proposed by Gross and John (2003) and the Spanish adaptation by Cabello et al. (2013). This reaffirms the instrument’s ability to directly link the scores obtained on its items to the specific trait being evaluated in the Colombian population context, which, in this case, is emotional regulation. Consequently, this study allows us to affirm that the ERQ test is sensitive enough to assess the ability of Colombian people to adequately interpret the emotional regulation demands made in specific social interaction situations, as well as interpersonal differences to adjust behaviour, based on said context requirements (Appleton & Kubzansky, 2014; Gross, 2015; Seligowski & Orcutt, 2015).

This makes it possible to confirm that both the reappraisal and suppression subscales adequately discriminate difficulties in emotional management in social situations, potentially leading to emotional suppression and mood-related issues (Burton & Bonanno, 2016). These associations hold true regardless of sociodemographic variables such as gender (in line with the conclusions drawn by Pineda et al., 2018, among the Spanish population), the presence of stressful events, or occupa tional status. However, regarding age ranges, there is a likelihood that the test may not maintain invariance, which is consistent with the findings of Knäuper et al. (2016). As such, it is advisable to consider applying the test to a probabilistic sample to create distinct scales and cutoff points that account for the physiological reactivity changes and psychosocial adjustment processes characteristic of various life stages (Isaacowitz, 2022).

When comparing the internal consistency, it becomes evident that the reliability achieved by this full version, as well as by the factors comprising the instrument, is on par with, if not higher than, that reported in the original test by Gross and John (2003). Notably, it surpasses the Latin American adaptations by Braule-Pinto et al. (2021), Gargurevich and Matos (2010), and Moreta-Herrera et al. (2018). Even though this may be due to the use of a large sample, the indicators ensure that the measure is stable regardless of the population with which it is used or the moment in which it is applied (Frías-Navarro, 2022). However, these psychometric conditions in the Colombian version could be improved with paper-and-pencil applications. Such applications contribute to data collection comprehensiveness, response rates, and data quality, as demonstrated by Díaz de Rada (2012), especially in comparison to results obtained through the use of Information and Communication Technologies.

The significant correlations found between the dimensions of each instrument show that the comparison of the ERQ with the FREE Scale ensures the convergent validity of the instrument; In line with this, Gross and John (2003) concluded that the reappraisal of emotions is considered an adaptive ER strategy, therefore, the results with the reappraisal dimension of the ERQ are consistent with those that make up the FREE Scale (Gómez -Acosta, 2022).

However, it’s important to acknowledge several limitations of this study. Given that it relies on self-report measures, certain variables come into play, such as the estimation of potential behaviours in the provided scenarios, which are based on memories and subjective affective evaluations (Demetriou et al., 2015). Similarly, as it is a self-administered test completed via an online form, uncontrolled situations may arise that affect participants’ engagement and attention (Dang et al., 2020).

Moreover, in line with the findings of Cabello et al. (2013) and Balzarotti et al., (2010), it’s important to note that while the psychometric results are generally favourable, emotional regulation is heavily influenced by the cultural considerations within which individuals operate (Curhan et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2014; Luong et al., 2016). In this context, it is advisable for future studies to employ larger and more representative samples, along with assessments of temporal invariance (Pineda et al., 2018). Furthermore, studies should also consider the cultural framework to which individuals subscribe. Additionally, it is beneficial to explore comparisons between psychometric results obtained from self-report instruments and data gathered through psychophysiological instruments that record emotional disturbances caused in real or simulated situations while controlling for various variables (Burton & Bonanno, 2016; Kobylińska et al., 2023).

In conclusion, the ERQ is an instrument that manifests optimal psychometric properties to adequately measure the levels of cognitive reappraisal and emotional suppression in Colombian adults. Consequently, this instrument can be considered suitable for use in the general population as part of assessments in primary care, facilitating the direction of both health promotion and preventive actions in the realms of physical (Giuliani & Berkman, 2015; Gómez-Acosta & Londoño, 2020; 2021), and mental health (Berking & Wupperman, 2012; Carpenter & Trull, 2013; Sloan et al., 2017). In addition, the adequate psychometric indicators obtained by the ERQ suggest its applicability in research aiming to analyse the relationship between emotional regulation and other psychological processes (Ford et al., 2019; Gross, 2015, 2024).1 2