1. Introduction

Social reality is constructed from the collective imagination of all individuals (Searle, 1997). In this process, a social order is created, manifested in social norms and institutions that constrain action (North, 2006; Williamson, 1989), becoming an extension of human reason itself (Castoriadis, 2013). However, considering that people can change their minds, begin to think differently, and include the dynamics of institutional change, it becomes evident that there are no aspects that can be determined as exact and immutable, and the image of social order becomes more complex. This distinction sets social sciences apart from exact sciences and, consequently, differentiates their research methods (Bunge, 1999; 2004).

In the exact sciences, there are techniques, measurements, and concepts that are constant and can be applied in measurements regardless of context, location, or form. The research methods in the exact sciences are standardized because the nature of their objects of study allows it (Bunge, 1999; 2004). In social sciences, regarding social reality and human behavior, this is a challenge. Therefore, social research methods are often questioned by some researchers for an alleged lack of objectivity, due to their variability and wide range of techniques and methods (Lozano Ardila, 2017; Martínez Ruíz and Benítez Ontiveros, 2016). However, those who make this critique often overlook that these characteristics are inherited from the very object of study. Consequently, observing social phenomena and individuals themselves is a complex process.

This complexity prompts a view that qualitative and quantitative aspects should be seen as tools of knowledge that can be employed as an amalgam according to the needs of the research. It encourages the gathering of different perspectives and studies that fit within what could be considered holistic, transdisciplinary, and interdisciplinary methodologies. It views research partly as an art without predetermined rules (Feyerabend, 1975).

Given this context, this document reflects on a social research method that allows for the examination of such phenomena in a way that some of the characteristics that are difficult to measure or quantify can be operationalized. Therefore, the purpose of this writing is not that of a traditional research article aiming to present the analysis of data through a given methodology, but rather to present and reflect on a method, using supportive elements - such as exemplifications of its use - for greater justification. This method emerged as part of a research training exercise in undergraduate programs in administrative sciences to understand part of the heuristic process in research methodologies, and thus it is presented as a useful framework for such training.

To fulfill this purpose, a practical case will be used as an example. It is reiterated that the practical case does not serve as a traditional framework of results and analysis, but solely as a means to illustrate the use of the method. The practical case to be exemplified refers to the reasons that motivate university students to undertake or not undertake entrepreneurial activities. This methodological exercise was carried out as part of the research project titled "Análisis de las variables características de propensión al emprendimiento de los estudiantes UNIMINUTO de la rectoría Suroccidente - RSO".

Accordingly, the document initially presents a contextual discussion on qualitative and quantitative approaches in the research of social phenomena. Then, the theoretical foundations of the process of operationalizing qualitative data are presented as the central framework for reflecting on this methodological proposal. Subsequently, the practical case related to the entrepreneurial decisions of students from a higher education institution in Colombia is developed, where the procedures of operationalizing qualitative data are applied, accompanied by their respective theoretical reflections.

On Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Social Phenomena

A significant part of the difficulty in addressing some of the diverse objects of study in the social sciences lies in the ontological complexity of the phenomena or facts from which these objects of study are constructed (Bourdieu, Chamboredon and Passeron, 2002). This complexity has sparked a broad methodological debate in the social sciences, which includes questioning the type of knowledge that this science should seek (Mardones, 2015). While this methodological discussion has many facets and versions, it is often presented through two classical stances that facilitate its understanding.

The first stance asserts that a certain methodological monism of the sciences should be maintained, so that social and natural sciences share at least some methodological elements, where quantitative methodologies are favored. According to Mardones (2015), these methodologies derive from a methodological tradition he calls the Galilean tradition, whose goal is to find the efficient causes - or explanations -of phenomena. The second stance argues that the ontological basis of natural and social phenomena is so distinct that there cannot be a universal set of methodological elements that encompasses both social and natural sciences. Therefore, for the first type of sciences - social sciences - qualitative methodologies should be favored for ontological coherence. These methodologies in the social sciences stem from a methodological tradition that Mardones (2015) terms the Aristotelian tradition, whose purpose is to find the final causes - or understandings - of social phenomena.

The intriguing aspect of this discussion, which is attractive for the present work, is that this methodological problem does not necessarily have to be seen as an epistemic barrier preventing the transition between qualitative and quantitative approaches in the social sciences. That is, while it is indeed assumed that natural and social phenomena possess different ontological bases - a matter that, however, heavily depends on the intellectual orientation of the researchers - this does not mean that social phenomena cannot be approached qualitatively or quantitatively. Reality is not ontologically qualitative or quantitative - qualitative and quantitative aspects are not two facets of the world - but rather, qualitative and quantitative approaches are epistemological ways of approaching phenomena in research (Díez and Moulines, 1997).

Accordingly, the objects of study in social phenomena can be approached both qualitatively and quantitatively. Depending on the epistemic objectives pursued and the intellectual orientations of the researchers, one approach or the other will be employed, resulting in types of data with different natures that are susceptible to analysis. In fact, certain research problems address social phenomena of such complexity that a situation might arise where it becomes necessary to approach them both qualitatively and quantitatively, to varying degrees and forms, as the case may require.

The Operationalization of Qualitative Data

As outlined in the introduction, the purpose of this work is to present and reflect on a methodology, not to present a methodology followed by data analysis. Therefore, the aim of this section is to introduce the proposed methodological framework. In this context and considering the synthesis of the previous discussion between qualitative and quantitative approaches, it is epistemologically conceivable to propose methods to transform qualitative data types so that they can be measured. For this, it is necessary to understand that some research, due to the nature of their objectives or research problems, or the requirements of some applied studies, needs measurable elements.

The foundation for this refers to what Cea D'Ancona discussed regarding the process of concept operationalization. According to this author, the notion of operationalization originates from the natural sciences and refers to the process in which measurements are assigned to concepts (Cea D'Ancona, 2001). This process is considered an intermediate methodological phase where, from concepts, "empirical variables or indicators" are established for respective contrastation with reality (Cea D'Ancona 2001, p. 113).

This method can be applied to the study of social phenomena, considering the points already mentioned. Firstly, social phenomena, like any other phenomenon, can be subsumed into concepts (Díez and Moulines, 1997). Then, depending on the complexity of the social phenomenon studied, these concepts are often broken down into dimensions for respective analysis. Such breakdown into dimensions also depends on the different emphases of the disciplines addressing the social phenomenon. Each dimension of the social phenomenon studied can be disaggregated into types of qualitative data, which are used to gather information about aspects of reality related to that dimension of the phenomenon. By their nature, these types of qualitative data do not provide measurable information, leading to the process of operationalization, in which a way to quantitatively interpret the qualitative data is sought, giving it a numerical value. However, various difficulties associated with the complexity of the phenomenon and the limitations of associated abstraction processes come into play in this process.

To illustrate this, consider the study of complex social phenomena like decision-making. Studying some decisions made by individuals is complex due to the vagueness of the reasons constraining this action (Sánchez Sánchez, 2007). Like other social life phenomena, "[...] decisions are abstract constructs and, therefore, not directly observable" (Cea D'Ancona 2001, p. 115). For this reason, measuring why a person makes a decision about something requires breaking down this phenomenon by conceptualizing it into dimensions (Arenas-García 2021; González Blasco, 1986). This action involves identifying concepts that comprise the phenomenon, generally known as factors (González Blasco, 1986). However, González Blasco mentioned that "by performing this operation, one gains in precision but loses in richness, as generally, no matter how many dimensions are considered, all the aspects that a complex notion entails are never taken" (1986, p. 213).

Social facts are complex and difficult to observe broadly (González Blasco, 1986). Therefore, González Blasco mentioned that an agreement should be reached on the number of dimensions to be used for measuring the phenomenon in such a way that its understanding, operationalization, and complete delimitation are not hindered (1986). To determine the quality, quantity, and relevance of the dimensions, approximations and validity tests must be executed (González Blasco, 1986; Rodríguez Medina et al., 2021). Regarding this, González Blasco considered that:

There are no theoretical rules to determine the dimensions to be considered in a concept. In many cases, it is the intuition and experience of the researcher that sets the limits of the most representative dimensions of a concept, either by analyzing the concept itself or by empirically deducing these dimensions; applying the results of previous studies. (González Blasco, 1986, p. 213)

Similarly, some authors suggest validating the dimensions found through expert contrastation (Escobar-Pérez and Cuervo-Martínez, 2008; Rodríguez Medina et al., 2021). However, this step is often used methodologically more to identify the validity of the instruments (Escobar-Pérez and Cuervo-Martínez, 2008). For this purpose, literature reviews or results from empirical observations are more commonly used (Escobar-Pérez and Cuervo-Martínez, 2008; González Blasco, 1986).

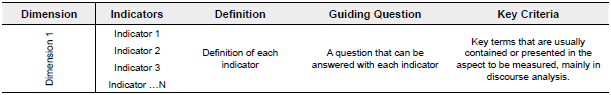

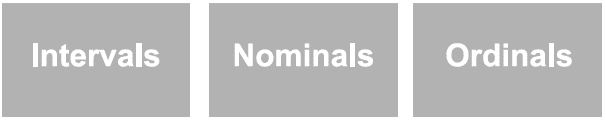

While these dimensions are parts of a concept, they correspond to qualitative properties that allow the classification of individuals or observed social phenomena into a limited number of categories (López-Roldán, 1996). Procedurally, dimensions correspond to categories that can be identified in the individual or social phenomenon. The observer is an individual or group, and each observation or finding is a reflection of the observed phenomenon grouped into symbolic representations or variables (González Blasco, 1986). These symbolic representations can be understood as socio-semiotic codes from the hermeneutics of cultural analysis (González Rojas, 2016). These variables can store interval, nominal, and ordinal data, making the dimensions of these same types (González Blasco, 1986; Dettori and Norvell, 2018), Figure 1. For the first type of data, intervals are understood as discrete data grouped into scales, indivisible, with no absolute zero. The scale is arbitrarily selected to organize data, but all maintain an equivalence in the unit of measure (Dagnino, 2014; Vargas Franco, 2007).

Source: Own elaboration based on González Blasco (1986)

Figure 1 Types of Qualitative Data Susceptible to Measurement

The following data are nominal. These, in turn, represent qualities usually referred to as labels. Generally, these labels do not possess a usual numerical meaning; they are non-metric and it is impossible to indicate which category is better than another (Vargas Franco, 2007; Dettori and Norvell, 2018). Additionally, they are often dichotomous, taking only two values, such as alive or dead (Dagnino, 2014; Kara, 2023). Dagnino considered that this

is the weakest level of measurement. Numbers or other symbols are simply used to classify an object, person, or characteristic. In a nominal scale, the operation involves dividing a given class into a set of mutually exclusive subclasses. The only relationship involved is equivalence, symbolized by the sign =, or its absence, by the symbol (2014, p. 110)

The last type of data, ordinal, accounts for a quality and not a quantity. Like nominal data, numbers are usually understood as labels. However, ordinal data differ from nominal data in that the labels must retain the characteristics of the numerical system, represent the characteristics of the object being measured, and generally have a logical valuation (Vargas Franco. 2007). Moreover, these data must a) include at least three possible values and b) have a total limit of options (Dagnino, 2014). The most commonly used form of ordinal data is the Likert scale (Maldonado Manzano, Manaces Esaud and Piñas Piñas, 2022; Lalla, 2017).

Thus, these three types of data comprise dimensions that are, in turn, composed of variables or groups of variables. The number of variables, as well as the number of dimensions, depends on the type of data to be measured, the phenomenon, and the contrastation made between the two. This process usually identifies the aspects to be observed (Merton, 2002) which, in this type of research, are generally considered indicators (González Blasco, 1986).

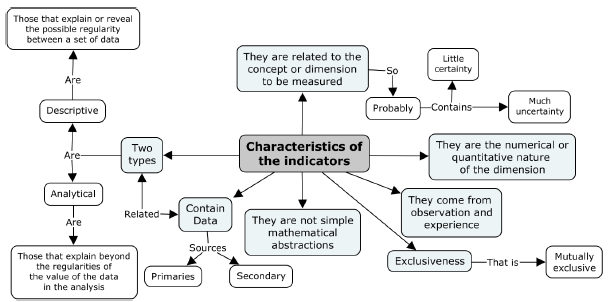

For González Blasco, indicators can be understood "[...] as measurement instruments that concretize observations and make the dimensions of the considered concept quantitatively measurable" (1986, p. 217). Indicators can be understood as operational terms (Cea D'Ancona, 2001 ). Expressing dimensions in terms of one or more indicators achieves a beneficial concretion, as it allows for numerical manipulation and its relation to other dimensions. However, this concretion results in the loss of part of the conceptual richness of the observed phenomenon (González Blasco, 1986). Now, according to González Blasco, among all the characteristics of indicators (see Figure 2), there are two that he considered essential: "a) being related to the concept or dimension they intend to indicate; and b) being a numerical, quantitative expression of the dimension they reflect" (1986, p. 217). In addition to the above characteristics, this author mentions that other secondary characteristics specific to the dimension to be measured must be considered.

Source: Own elaboration based on González Blasco (1986) and Cea D'Ancona (2001)

Figure 2 Characteristics of Indicators

For the development of social research indicators, there are no guiding patterns that guarantee objectivity as with economic indicators. There is no standard, but it is possible to refer to sources of information such as previous research on the studied field. This gives some validity to the indicators as they have been sufficiently contrasted (González Blasco, 1986).

Once dimensions and indicators are identified, the operationalization of information is posible (Cea D'Ancona, 2001; López-Roldán and Fachelli, 2015). For this, it is recommended to formulate guiding questions that direct the sense to be given to the analysis of the phenomenon to be observed (Cea D'Ancona, 2001; López-Roldán and Fachelli, 2015). This action further delimits the number of indicators for each dimension, in line with what González Blasco (1986) proposed. Below is a general schema for the operationalization of qualitative variables that can be applied for a general analysis of this type,Table 1.

Similarly, Salcedo Serna considers that this method allows for the formulation of guiding questions whose answers can be considered research hypotheses (Salcedo Serna, 2021), see Table 1. It is also possible to identify terms or key criteria that facilitate the observation process. These key criteria arise from the question, or the identification of the possible content subsumed in the dimension and the indicator. The use of key criteria is optional and is often employed in some research, particularly based on discourse analysis.

Practical Case of Operationalizing Qualitative Data

As outlined in the introduction, this practical case does not aim to present results or analysis of results from a traditional research article but serves as an argumentative and supportive element to illustrate the methodology being presented and reflected upon. This practical case was derived from a research training exercise, assuming that, in general, the proposed methodology can be used for students to reflect on the qualitative and quantitative aspects, overcoming orthodox discussions around research.

Regarding the practical case, it involves a study exercise on entrepreneurial decisions. Analyzing the decisions of groups of people is complex due to the various options each of their members can have individually. For the case of the decision to undertake entrepreneurship, it is possible to identify several deciding factors such as: a) tolerance to uncertainty, b) social conditions, c) risk aversion, d) personal characteristics, e) technical or practical knowledge of an activity, f) political factors, g) educational level or influence of education, among others that may positively or negatively influence a person's decision (Lemos Bernal and Londoño-Cardozo, 2024; Ramírez Maya, Tierradentro and Londoño-Cardozo, 2023). Therefore, to identify the factors that could influence the decisions made by a group of university students in Colombia, it was necessary to apply the method of operationalizing variables presented in the previous section. This procedure made it possible to identify the dimensions and indicators that could be assessed in the population under study.

The operationalization of variables in this study was carried out through a systematic literature review. For this review, keywords such as 1) sociodemographic factors, 2) risk aversion, 3) decision making, 4) entrepreneurship, 5) entrepreneurial intentions, 6) entrepreneurial attributes, among others, were used. All types of documents suitable for a systematic literature review according to García Molina and Chicaíza Becerra (2011) and corresponding to the period 2010 - 2022 were considered valid. Additionally, all criteria for a systematic literature review in social sciences outlined by Chicaíza-Becerra et al., (2017) were followed.

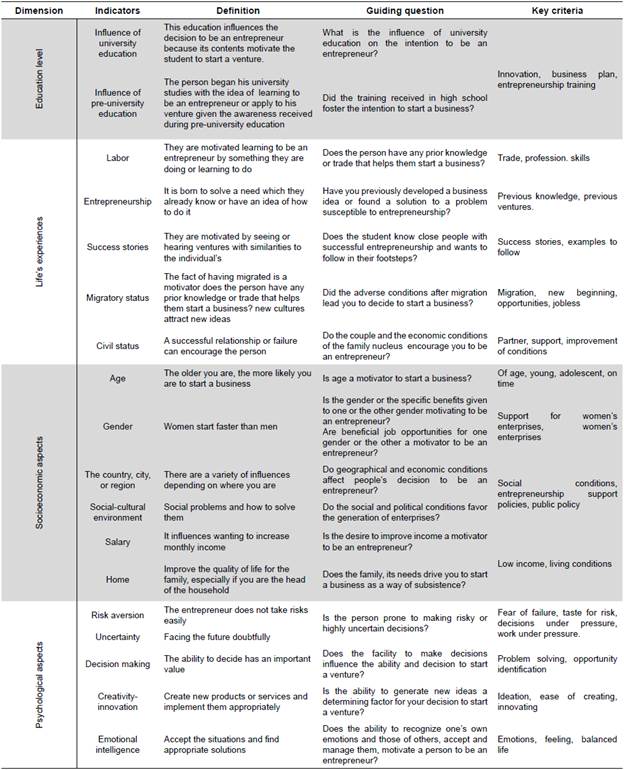

All this information was synthesized into a bibliographic matrix. This allowed the identification of dimensions that can be considered to analyze university students' decisions about becoming entrepreneurs or not. In general, four dimensions were identified: a) education, b) life experiences, c) socioeconomic aspects, and d) psychological factors. These dimensions are described in more detail below.

The first dimension to consider is the level of education, which significantly influences the decision to undertake entrepreneurship (Rocha Jácome and Giraldo Gómez, 2015; Torres-Ortega and Campos, 2021). This impact manifests through both the individual's prior training and educational sensitization processes. It has been established that a higher educational level increases the probability of starting an entrepreneurial venture (Villarreal-Álvarez and Roque-Hernández, 2022), especially when possessing prior technical knowledge before university education (Salcedo Serna, Londoño-Cardozo, and Gaitán Vera, 2021). However, a higher educational level can also lead to the decision not to undertake entrepreneurship, opting instead for academia, research, or high-ranking public or private positions (Villarreal-Álvarez and Roque-Hernández, 2022; León Mendoza, 2017). Thus, the educational level emerges as a crucial dimension in the decision to undertake entrepreneurship.

For the case of Colombia, this dimension can be subdivided into two indicators. The first refers to the educational level in the country, classified as: a) university education, b) secondary education, c) primary education, or d) no edu cation (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2011). Estrin, Mickiewicz and Stephan (2016) and Johansson (2000) highlight the importance of these educational levels. The second indicator suggests that university education has higher added value if it is technical, technological, or professional (Orozco Castro and Chavarro-Bohórquez, 2008; Schlaegel and Koenig, 2014; Villarreal-Álvarez and Roque-Hernández, 2022).

The second dimension includes the life experiences of the students (Hossain, 2021; León Mendoza, 2017), with indicators such as: i) accumulated work experience (Poschke, 2013a; 2013b; Serrano Orellana, Pacheco Molina and Barriga Arizabala, 2017), where entrepreneurship arises from the desire to solve a current need using previous knowledge (Serrano Orellana, Pacheco Molina and Barriga Arizabala, 2017; Salcedo Serna, Londoño-Cardozo and Gaitán Vera, 2021); ii) success stories influenced by examples of family members, acquaintances, or friends who undertook entrepreneurial ventures (Chen, Greene and Crick, 1998; Krueger, Reilly and Carsrud, 2000) iii) migratory status, where crises force migration, applying previous knowledge in new contexts (Vinogradov and Kolvereid, 2007; Webster and Kontkanen, 2021); and iv) marital status, with the influence of partners, children, or dependents and household size (Gluzmann, Jaume and Gasparini, 2012; Mendoza et al., 2021; Serrano Orellana, Pacheco Molina and Barriga Arizabala, 2017).

The third dimension focuses on socioeconomic factors, considered the most influential in the decision to undertake I entrepreneurship (Contreras Torres et al., 2017; León Mendoza, 2017; Navarrete Fonseca, 2019; Rocha Jácome and Giraldo Gómez, 2015). Society faces multiple problems that, once analyzed, can be solved through innovative entrepreneurial ventures (Ibarvo Urista, Quijano Vega and Loya Olivas, 2018). León Mendoza (2017) mentions that living conditions and poverty stimulate economic models that influence the decision to create a business.

The indicators in this category include: age, with studies indicating that people over 25 years old tend to undertake entrepreneurship more than younger individuals (Oelckers, 2015; Ortega-Lapiedra, 2020); gender, where women show a greater propensity to undertake entrepreneurship (Figuerola Ferretti Garrigues, Aracil Jordá and Infante Infante, 2022; Gutiérrez Rodríguez, Winkler Benítez and Campos Sánchez, 2021); geographical location, with people responding to local needs (León Mendoza, 2017;Torres Marín, González Rodrigo and Bordonado Bermejo, 2019); socio-cultural environment, which can favor or hinder entrepreneurship (Contreras Torres et al., 2017; Krueger, Reilly and Carsrud, 2000; Mancilla and Amorós, 2012) salary, which may not cover basic needs, prompting the search for additional income (León Mendoza, 2017; Torres Marín, González Rodrigo and Bordonado Bermejo, 2019); and the household, as a key motivator for improving quality of life (Gholami and Tahoo, 2021 ; Kautonen, Kibler and Minniti, 2017; Zahra and Wright, 2016).

The fourth dimension encompasses psychological factors, including several indicators. The literature establishes a strong relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and motivation (Bravo García et al., 2021). Adequate motivation balances emotions and responsibility, allowing goals and objectives to be achieved (Alzate Rodríguez and Bravo Santacruz, 2018; Bravo García et al., 2021; Morán Astorga and Menezes dos Anjos, 2016). However, motivation is difficult to quantify, so various asymmetric traits are identified among university students: a) risk aversion, b) uncertainty, c) decision-making, d) creativity and innovation, and e) emotional intelligence.

Regarding risk, individuals may choose to face or avoid high risk (da Silva, 2014), with a general fear of failure (Ferrándiz, Conchado and García-Martínez, 2021). Entrepreneurs with knowledge in financial, economic, political, or business areas tend to take calculated risks (Benítez Aguilar and Riveros Paredes, 2022), aware of a 50% probability of success (Rocha Jácome and Giraldo Gómez, 2015). Uncertainty, a relevant characteristic in entrepreneurship, makes university students overanalyze future situations, generating doubts (Bridge, 2021; Rocha Jácome and Giraldo Gómez, 2015).

Decision-making, discussed in the third point, requires strong will (Lozano Frutos, 2014), and having group support is crucial (Ajzen 1991; Lozano Frutos, 2014; Rocha Jácome and Giraldo Gómez, 2015). Creativity and innovation, essential for entrepreneurs (McGee et al., 2009; Mueller and Thomas, 2001 ; Popescu et al., 2016) are influenced by personality and the ability to perceive and apply external factors (Zahra and Wright, 2016). Finally, emotional intelligence is crucial for managing various situations and emotions, adapting to carry out ideas and projects (González Sierra, 2015; Morán Astorga and Menezes dos Anjos, 2016; Orozco Castro and Chavarro-Bohórquez, 2008).

To illustrate the exercise of operationalizing these dimensions and their subcategories, a Table 2 was prepared, organizing each dimension, its indicators, the guiding question, and the key criteria that must be considered for the subsequent analysis of the data collected with the project's instruments. The results of these analyses can be reviewed in the works of Imbachi Quinayas (2023), Ramírez Maya, Tierradentro and Londoño-Cardozo (2023) and Londoño-Cardozo, Maldonado Vásquez and Taype Huaman (2024), among others.

Table 2 Operationalization of variables in the case of the decision be an entrepreneur in university students

Source: Own elaboration based on Lemos Bernal and Londoño-Cardozo (2024) and Lemos Bernal (2022)

2. Conclusions

The operationalization of qualitative data types is a social research method that provides an alternative for studying social phenomena that have been independently examined. The strength of this method lies in its ability to combine different analytical perspectives within a single study and to interpret qualitative data using quantitative techniques.

This approach considers one of the discussed assumptions. The reality of research continuously blurs methodological traditions and necessitates the creation of new alternatives to address the complexities of its subject matter. This aligns with epistemological anarchist perspectives, which assert that scientific research is not linear nor bound to strict rules. Research, in essence, has two modes of existence: order - within the frameworks institutionalized by research communities -and chaos - for change, revolutions, heuristic processes, and the creation of methodologies. Therefore, research, particularly in its evolutionary changes and revolutions, must dare to look beyond the established norms in accordance with the complexity of its objects of study and the need to forge new paths for knowledge.

Although this method can be essential for holistic, transdisciplinary, and interdisciplinary methodological approaches, certain limitations must be considered.The potential to establish an indeterminate number of dimensions does not guarantee that all characteristics of the phenomenon will be covered. Consequently, social phenomena can never be studied comprehensively. Additionally, operationalizing these phenomena may lead to a loss of conceptual richness. However, it achieves precision aligned with the interests of the research.

Furthermore, this method is particularly suitable for application in formative research. The experience gained from this research project suggests that, for students, it is relatively easy to identify the dimensions of these complex phenomena from the literature, even if their measurement is challenging. Thus, establishing a solid foundation that enables them to effectively execute their projects and achieve their objectives facilitates their work and motivates them to delve deeper into the study of these phenomena. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that this method is also useful, and indeed should be utilized by experienced researchers when they wish to quantitatively analyze complex phenomena, such as business decision-making or expert opinions on various topics.

text in

text in